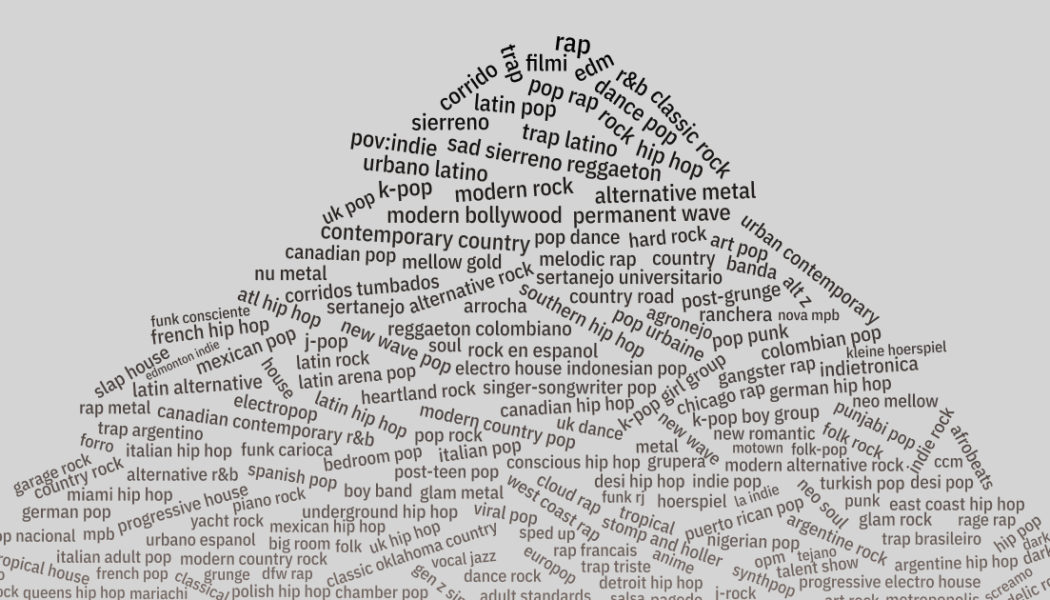

In 2016, Spotify began publishing a list of the most popular music genres on its platform.

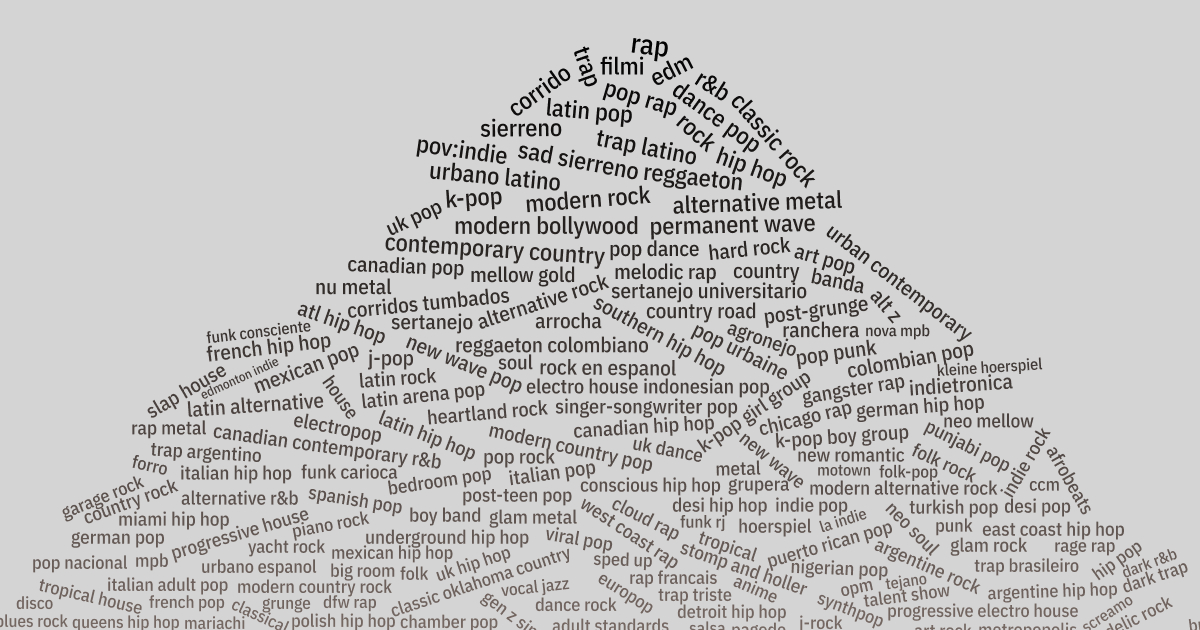

Here’s the list again, seven years later in 2023.

I’ve highlighted the genres that were not in the top 25 seven years ago. Why did so many genres shift in popularity?

This led me down the rabbit hole of exploring the full list of Spotify’s genre database.

This database has over 6,000 genres, and it’s changed the way that I think about music. But before we explore why Spotify is tracking so many genres, let’s start with the preceding question: why are top genres so different in 2023 versus 2016?

First, note how many of 2023’s top genres are generally performed in Spanish, Korean, or Hindi.

This shouldn’t be surprising.

Today, Spotify users from North America and Europe represent a much smaller share of streams than in 2016.

Every year, Spotify is available in more countries, such as India in 2019 and South Korea in 2021. Fittingly, you can see genres with artists primarily from countries in Latin America, Asia, and Africa begin to dominate in popularity.

So many non-English genres have ascended in popularity: K-pop is, by far, the biggest gainer since 2016. Over the past 7 years, it grew to the 17th most–streamed genre.

K-pop now has more streams than r&b and edm.

You’ve probably heard of Bad Bunny, the world’s most–streamed musician, three years running. Reggaeton has similarly exhibited a K-pop–like ascent.

But is reggaeton seemingly pervasive because we’re finally counting popularity on a global stage? Is K–pop’s ascent driven by Spotify finally tapping into the taste of music fans in more countries?

Popularity is such a self–fulfilling loop: we obsess over what’s popular (especially in the US), pushing top–charting artists further into the cultural spotlight.

Next, we’re going to look at what’s beyond the top 25. Music nerds, this section is for you.

Below the top 25 ranking are genres #26 to #6,000 (and counting), all part of an on–going effort to catalog every music community.

This effort is continually evolving.

For example, latin reigned as a top 10 genre until it was dropped from Spotify’s genre classification entirely in late 2022.

Before it was removed, Latin seemed like a vestige of the record store days, a potpourri of anything Spanish–language, from Juan Gabriel to Bad Bunny.

Spotify’s Latin genre already overlapped with other genres like Latin Pop, so Spotify removed it and subsequently added Urbano Latino to its genre list, which is narrower in scope than Latin, centered more on reggaeton and trap.

Hip hop and rock are similarly so broad that if I were to tell you that they were ranked #4 and #5 respectively, that wouldn’t say much.

For example, consider the different sounds of these “hip hop” tracks.

Hip hop has evolved so much over the past 50 years; today it’s a kaleidoscope of varied sounds and communities. Spotify has hundreds of genres that overlap with hip hop, and many were added in the past few years.

So Spotify’s genre catalog not only recognizes the breadth of music within hip hop and other genres, but identifies new styles as well.

Here are the latest genres added in 2023 (note: some have always existed, but were just recently added to Spotify’s dataset).

Some of these genres might seem made–up by Spotify; that’s because a few are. Glenn McDonald, who leads much of Spotify’s genre research, elaborated in an interview that genres can come from users’ listening patterns.

An example of a genre that’s driven by “listening patterns” includes escape room, Spotify’s 260th most streamed genre. McDonald describes it as, “The vibe is kind of an underground–trap/PC–music/indietronic/activist–hip–hop kind of thing.”

This goes for older music too. Rock music is so diffuse that it makes sense to retroactively further catalog it. This includes, for example, mellow gold (which has “elements of soft rock and folk rock, with emphasis on clean production, harmonies, and melodic compositions”).

I’ve seen pushback to these genres, especially the ones that only exist in Spotify’s data. They often show up on the “top genres” list for users’ year–end report.

I get it. Spotify’s stomp and holler genre is described by McDonald to include “those rousing neo–rustic folk/pop–ish artists, like Mumford & Sons and the Lumineers, that kind of sound like Dave Matthews ran over a jug band.”

But I will never be caught dead saying, “I listen to stomp and holler.”

Come to think about it, that goes for many nascent genres. If I described my music taste as drift phonk, math rock, or bedroom pop, it would sound cringey and pretentious.

That goes for new mainstream genres too. Spotify is credited with coining Hyperpop, which is now a part of popular culture and music discourse. But that didn’t stop it from being ridiculed.

Artists, especially, seem to struggle when their music is associated with new genres.

Consider yacht rock: coined in the late ’00s, it describes the feel–good ’80s grooves of bands like the Eagles, Doobie Brothers, and Daryl Hall & John Oates.

Yacht rock is the 154th most–streamed genre on Spotify, even though John Oates (the “Oates” of Hall & Oates) had never heard of the term.

Artists rarely have control over how their music is categorized. Lil Nas X’s “Old Town Road” stirred controversy when it wasn’t initially classified as a country song by Billboard.

In a post–award speech, Tyler, the Creator pushed back at his Grammy nomination for Best Rap Album.

Tyler has a point. Billboard’s “Hot R&B/Hip–Hop Songs” chart was once named “Hot Black Singles” and even “Race Records,” all stemming from a 75–year effort to racially divide music charts.

All of the pushback against genre classifications are valid, whether that’s inventing escape room and stomp & holler or what qualifies as r&b vs. pop.

But I still think an always–updating catalog of 6,000 genres is groundbreaking.

I see this effort in the same way I see taxonomy: technically accurate, colloquially useless.

For centuries we had generic names to identify animals, such as “fish.” Everything from squid to crabs (and obviously jellyfish) were lumped into the same “fish” bucket.

But on closer inspection, most of these animals were not related at all. In a research context, scientists have drawn boundaries between animals that we mindlessly lumped together.

Similarly, the genre database adds much needed detail to broad categories, like hip hop and rock. For musicologists, it’s an anthropological gold mine. And for Spotify, it likely helps them better profile their users’ music tastes.

But these genres don’t necessarily work in casual conversation: you can describe your music taste as indie, even if, technically, Spotify says it’s escape room. The same goes for biology: people should call figs a fruit, even though it’s technically an inverted flower. Honey Badgers will always be badgers to me, even though they are more related to weasels.

This approach means we can catalog music scenes that culture is typically too slow to name.

Hip hop officially celebrates its 50th anniversary this year, so 1973 marks its birth, the year that DJ Kool Herc mixed three breakbeats together. But it wasn’t until the late ’70s that “hip hop” was actually coined.

The same goes for the Velvet Underground and the Stooges, the progenitors of punk, who both preceded the phrase “punk music.”

In 1969, Rolling Stone reviewed The Stooges first album, calling it, “rock and roll,” as well as “loud,” “high–powered,” and “raw energy.” Imagine the audacity should they have characterized it as the precipice of a new genre, “punk music.”

It’s hard to see how special something is, right in the moment.

If you’re old enough, you can look at the music scenes of your youth with awe, realizing that the pop music wasn’t just pop, but a marker of the era.

Right now, there’s some benign song that will, one day, represent a sound that’s quintessentially of the year 2023, and it will probably have a name.

There are over 100,000 songs published to Spotify daily. To classify this music is to examine the petri dish of music culture—one that is mutating and evolving in mere months—and attempt to sort it.

Here is a historic, publicly–available view of Spotify’s genre dataset, which was scraped from Every Noise at Once.