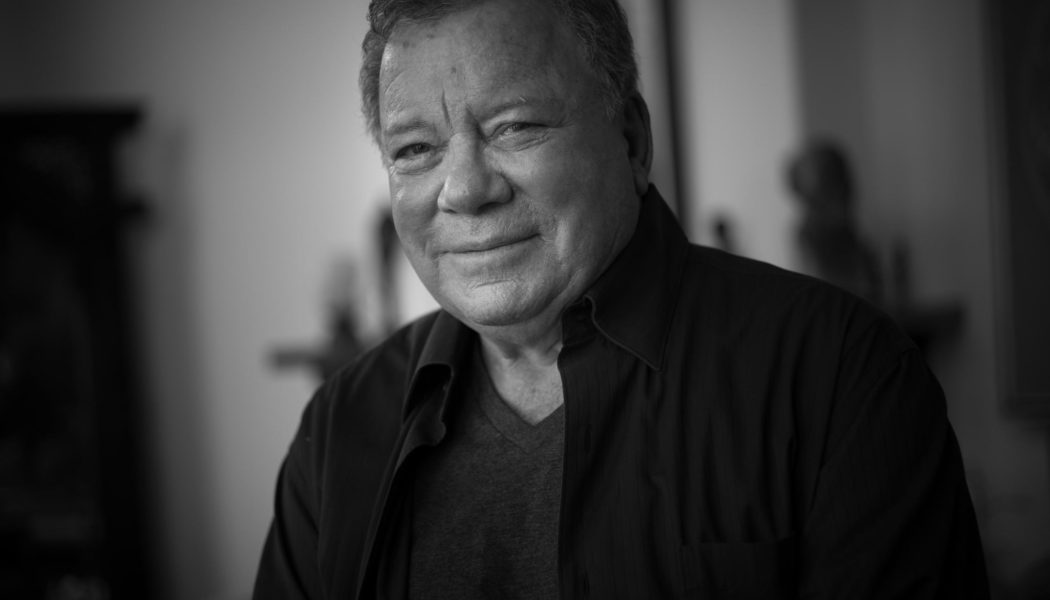

Before we could get anywhere near talking about his new album, Bill, on our scheduled Zoom call, William Shatner was already marveling at my beard. Now, it’s not the first interview to be disrupted by my ample facial hair, but it’s not exactly how I was planning to start my chat with the man behind Captain James T. Kirk, dozens of other characters from my childhood, and some of the most memorable cover songs in history.

Always the storyteller, Shatner gleefully launched into a memory of when he was once performing live and there was a man with a large beard in the audience.

“He was standing up, and I turned to his wife sitting next to him, and I said, ‘Do you like that beard?’” Shatner recalls in his now-legendary almost-hushed voice. “She looked at her husband and said ‘No!’ Obviously, in my mind, that was a moment. Can you imagine the wife beside the husband saying ‘I hate that beard!’ Does your wife love your beard?”

And that was the moment when I informed Mr. Shatner that not only does my wife love my beard (she handles its monthly trimming), but that she’s even said if I were to shave it that I would be single. Now, before we get too deep into the woods on Bill, I think it’s necessary to point out that my beard isn’t abnormally long. It rarely even covers my clavicle and is generally pretty well-maintained. It’s solid, but we’re not talking about something noteworthy like ZZ Top or Mike Beltran here.

With the beard discussion settled, Shatner was finally ready to discuss the topic of the day, his brand new spoken-word album created with the help of his friend Robert Sharenow and They Might Be Giants’ Dan Miller.

A couple of decades ago, a new William Shatner album would’ve seemed like a joke. His early efforts — beginning with 1968’s The Transformed Man — provided some truly unforgettable cover versions of well-known songs, but not exactly in the way that many artists would hope for. However, Shatner’s never been one to give up on things so easily. In 2004, he released the Ben Folds-produced Has Been, which only featured one cover and was generally received pretty well both by fans and critics. By the time he released his most recent album before Bill, he was topping the blues charts with last October’s aptly titled The Blues.

But now as he releases his most autobiographical album to date, the legendary showman is presented once again with a very familiar feeling.

“There was a time when I was doing a play that was going to New York and was being rehearsed here in Los Angeles,” Shatner begins. “We had an opening run in Los Angeles at one of the big theaters, and then after that we were going to Broadway. The actress in it was somebody, but I’ve forgotten her name. It was Mart Crowley who wrote it, and it was his next play after The Boys in the Band (1968). I don’t know whether that means anything to you, but The Boys in the Band was a big hit, so this was destined to be another big hit from Mart Crowley. The actress and I think it’s going to be a big hit, so we’re at the opening night in Los Angeles — in a big theater with a full house and all the critics — and the opening was designed to be the two of us coming out on the apron in darkness. We’re holding hands, the curtain’s about to come up, the lights go up and the play begins. The two of us are standing there for a beat or two while the audience quiets down, and she turns to me and whispers, ‘Are we in a disaster?’ and then the curtain comes up.

“I have been wary of every new thing that I begin ever since then,” Shatner continues. “Anytime I think ‘Yeah, this is really good,’ I have to ask the question of ‘Is this a disaster?’ So I can’t believe this album is so good to me. The three of us [Shatner, Sharenow, and Miller] think this is the cat’s meow. It’s the best thing we’ve done, and we did it over the pandemic by going on Zoom and sending messages back and forth. We loved what we were doing so much that we’ve got another album prepared, because we think this is that good. And then I feel that tickle of the question, ‘Are we in a disaster?’”

As Shatner knows all too well, it’s ultimately the audience that determines whether or not a project is a global hit or an unmitigated dumpster fire, regardless of if it’s an off-Broadway play, a blockbuster movie, a 100-episode TV series, or a spoken-word album featuring the likes of Joe Jonas, Joe Walsh, and Brad Paisley. The audience is “the final cast member” who doesn’t join the project until its release, but they can also completely override what everyone else involved feels and thinks about it. (“You’re in the studio and you think ‘Oh my God, this is so good.’ Then you send this precious thing out there and [critics] say it’s the worst thing they’ve ever heard. Then people go cry, and shots are heard in various bathrooms as they commit suicide because it’s so bad.”)

Although at this point in his career, Shatner’s developed thick enough skin that some heavy criticism won’t ruin him, he’s got more riding on this than most projects. Not only is it his pandemic album, but it’s also some of the most personal material he’s ever released in any format. On Bill, Shatner, Sharenow, and Miller explore a variety of genres and song structures to share stories from the actor’s life that he’d never told before — ranging from when he nearly drowned after leaving his rural Montreal home in his old Morris Minor to pursue his acting dreams (“The Bridge”) to the ongoing fear of dying alone (“Loneliness”) and how he constantly feels like he’s wearing a mask (metaphorically, not medically) both as an actor and in society in general (“Masks”). On one song, the 90-year-old songwriter even goes all the way back to grade school to share one of his earliest struggles in life.

“I’m Jewish, and when I was in early school — from about 5, 6, 7 until near my teens — I was at a very non-Jewish school,” Shatner says, taking a more serious tone for the first time in the interview. “They would say terrible things about me being Jewish, and I’d have to fight every day after school with two or three guys on me. I’d have to punch my way out of it. Then when the Canadian Jewish soldiers came back from the Second World War, there was no longer this notion that Jews were going silently to the ovens. By that time, I was already fighting my way through because I was Jewish, and it was forced on me. But a terrible thing happened along the way, and that is the inculcation of being called ‘a dirty Jew,’ and being smacked about it. You fight back, but at night as a child, you think ‘Am I a dirty Jew?’ One of the songs is about how do you get over that self image that’s pummeled into you? You can’t help but absorb it and say, ‘Well, are they right?’”

As for his signature delivery of these extremely personal stories, Shatner knows that he’s never going to be Frank Sinatra — or any other classically trained singer for that matter — but that he also provides something that no one else can. In a world where Shatner’s voice and cadence is so recognizable that you’ve probably heard it in your head while reading every one of his quotes, he doesn’t need to pretend to be anything he isn’t. In fact, he’s so committed to his style of dramatic reading that his unwillingness to give up or give in to the early criticism has a certain punk rock air about it. William Shatner doesn’t really care if people used to make fun of his musical stylings or don’t understand why he’s committed to putting out albums when most would just cruise on his acting career. He doesn’t have to, because he’s William fucking Shatner and he’s having a damn good time doing it.

“It fills me with joy to [perform music],” Shatner says. “I get a physical thrill out of doing it. When it happens and it works, I go ‘Wow, I really did it! I’m singing a song in my own way.’ I think maybe I’ve devised a whole new way of performing a song. It’s spoken, but it’s not spoken. When you hear some of the great singers speaking, I guess that’s what I’m doing up to a degree. If I hit it right, it’s thrilling to me.”