Country music, the century-old genre of nostalgia, tradition, and twang, has never been more in style. Last week, for the first time in the history of the Billboard Hot 100, the three most popular songs in America were country songs. One explanation for the milestone is that the genre’s artists and audiences are finally leaning into streaming: This year, country has experienced a 20 percent rise in listenership, a surge outpaced only by those of Latin music and K-pop.

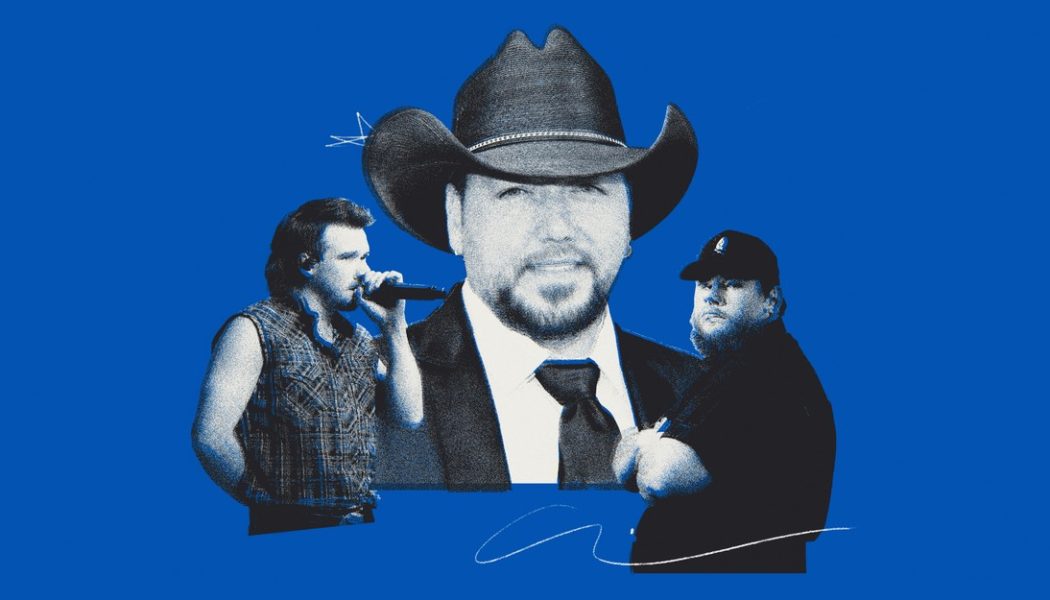

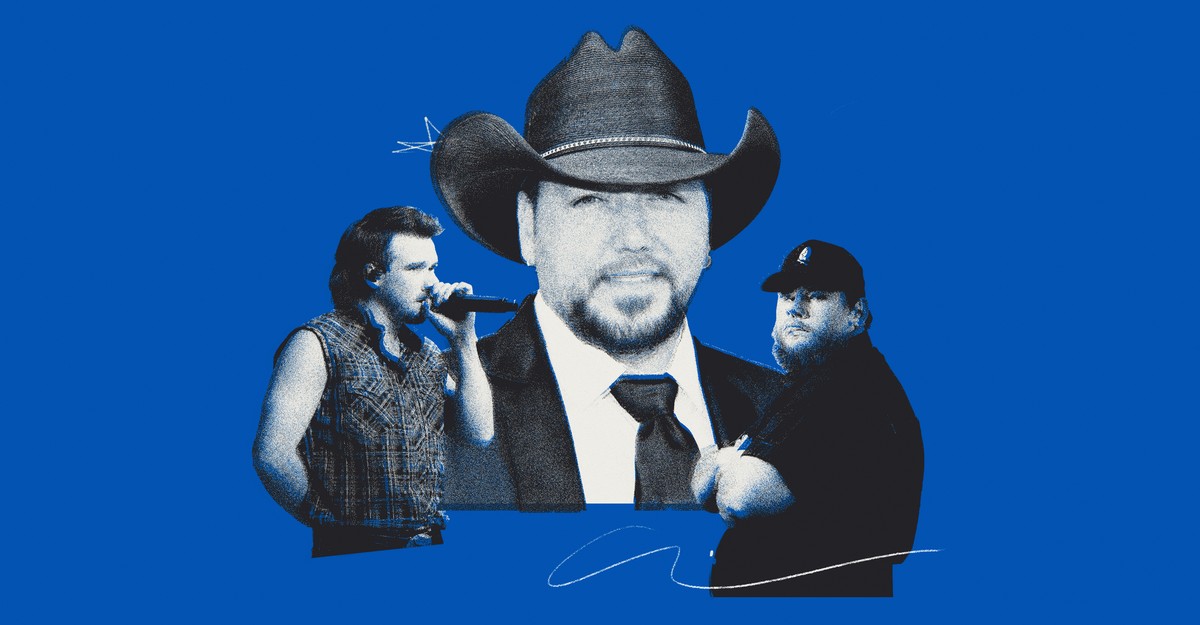

But this is a strange victory to celebrate—and not only because last week’s No. 1 song, Jason Aldean’s “Try That in a Small Town,” has proved to be a political flash point. The tracks breaking through right now each sound like something other than country. The genre always conveys some amount of underdog defiance, but lately, the music and the conversation around it have a distinct tinge of resentment.

In “Try That in a Small Town,” Aldean, the 46-year-old Georgia hitmaker, salutes supposedly rural values (honor, neighborliness, gun ownership) by warning the listener that supposedly urban pathologies (robbery, spitting at cops, burning flags) don’t fly in what some would call “Real America.” “Around here, we take care of our own,” he boasts. But the music hardly brings to mind peaceful pastures or sawdust-strewn saloons. As soon as I heard the song’s grumbling guitars, drooping minor chords, and riff ripped from Foo Fighters’ “Everlong,” I felt transported back to my suburban-male adolescence, circa Y2K—a time when I lived in an oversize black hoodie, listening to the groaning of men with soul patches. Aldean’s song is country in name, but its sound is post-grunge alternative rock.

In the early ’90s, Nirvana and its peers opened space for a new strain of mainstream manliness: vulnerable about feelings of failure and alienation, but with a hard, noisy edge that no one could possibly construe as sissy. Soon came a flock of melodically moaning bands, such as Bush, Creed, and Nickelback, that sheared grunge of its punk disposition, creating a broadly appealing template for directionless angst. Now Aldean has updated that template with pedal steel and right-wing talking points.

You’ve probably heard that the song is controversial. Aldean set a perfect discursive trap, taking advantage of America’s current split between two theories of its own history, and the predictability and profitability of backlash-to-backlash cycles. Though the song makes no mention of race, many listeners heard a dog whistle in it: The “good ol’ boy” vigilantism endorsed by Aldean’s lyrics has historically been affiliated with white-supremacist violence. His music video included images of Black Lives Matter protesters (though that footage was later edited out), and was shot in front of a Tennessee courthouse where a Black man was lynched in 1927. (The production company that made the video told The Washington Post that it had chosen a “popular filming location outside of Nashville.”) But critiques of the song have only amplified it: After Country Music Television banned the video, the track’s streams shot up 999 percent.

Aldean professes mystification at the dustup he’s provoked. The song, he has said, simply “refers to the feeling of a community that I had growing up.” (Aldean, for what it’s worth, grew up in the midsize city of Macon, Georgia.) This insistence, more than the southern lilt of Aldean’s voice, makes the track country. Aldean is working in a tradition of music that disses cities while celebrating rural can-do. But he’s not singing with the wry, plucky tone of Merle Haggard’s “Okie From Muskogee” or even with the gruff confidence of Hank Williams Jr.’s “A Country Boy Can Survive.” Nor is he delivering provocative slogans with the rock-star panache of Toby Keith. Rather, Aldean sounds wallowing and fearful in that distinctly post-grunge way—even as his words profess action.

Perhaps that vibe of sublimated anxiety reflects the tragedy underlying the song: small-town America’s decades-long economic decline. The big-city problems Aldean laments—violent crime, sedition, even fraying communal ties—are, in many cases, worse problems outside the cities than in them. This reality is a major driver of right-wing resentment—and music about it should, by all rights, have a hint of malaise. Aldean was previously known for anthems of carefree country living (although his 2018 single “Rearview Town” did almost seem like a dirge for rural dreams, it was actually a breakup song). A better precedent for “Small Town” is Staind’s 2001 hit, “It’s Been Awhile”: “It’s been a while / Since I could hold my head up high.” Not coincidentally, Staind’s Aaron Lewis is now a popular country musician—and one of the most effective right-wing protest singers in memory.

It’s also not a coincidence that Morgan Wallen—currently the most popular country artist by a wide margin, and the singer of “Last Night,” last week’s No. 2 song on the Hot 100—is a spiritual child of Nickelback. The Canadian rock band, famous for the catchy aughts rumble of “How You Remind Me” and “Photograph,” is often mocked as the ultimate example of musical blandness. But Wallen has unapologetically cited the group as an influence. His go-to producer, Joey Moi, produced many of Nickelback’s early-2000s hits, including “Photograph”—and then co-founded Big Loud, which is now one of the hottest labels in Nashville.

A 30-year-old former contestant on The Voice, Wallen is a serious pop talent, and “Last Night”—a sensation since its release in February—is excellent (which explains why it replaced Aldean’s track at the top of the Hot 100 today). There’s a bit of a Nickelback quality to the laminated nature of the production, and the way that the singer conveys a light hatred of himself, but “Last Night” mostly exemplifies a separate trend in Nashville: so-called hick-hop, modern country influenced by rap. Singing in a sassy twang about drunken fighting and reconciliation, over a brisk guitar loop and handclaps that form a syncopated beat, Wallen emanates the same sleazy charm as Drake. The irony here is obvious: In 2021, Wallen was caught saying the N-word on camera, which resulted in a supposed “cancellation” that, like Aldean’s, only boosted his listenership.

Last week’s No. 3 song in the nation, Luke Combs’s take on Tracy Chapman’s “Fast Car,” has created a little controversy as well. It is basically a note-for-note cover of a 1991 classic, differentiated mostly by the gruff beauty of Combs’s voice. After it began to rise in the charts last month, some commentators pointed out that neither Chapman nor any other Black woman had ever had the kind of success in country music that Combs is enjoying. This observation sparked conservative annoyance louder than the original critique, likely boosting the song’s popularity. As my colleague Conor Friedersdorf argues, the discourse around the song demonstrates how media coverage of race can inspire more confusion than reform.

But is it tenable to ask observers of this authenticity-minded, all-American genre to avoid speaking about conspicuous truths? The reality of country music’s Billboard Hot 100 takeover this past week is glaring. The music is diverse, but the performers aren’t: Between Aldean’s protest rock, Wallen’s laid-back rap flow, and Combs’s soul-folk cover, this boom for mainstream country is rooted not in sound but in white, male, and—at least in Aldean’s case—aggrieved identity. Of course, all genres are defined by demographics. But streaming technology, not to mention social and political media, now rewards the inflaming of passionate pluralities, including by sowing division. Inflaming stan versus stan, or right versus left, can prove profitable—at least for a short while (Aldean’s song today fell from No. 1 to No. 21 on the Hot 100).

Artists in other genres are going to learn lessons from this boomlet. Just a few days ago, Aldean made a surprise appearance at a Nickelback concert in Nashville. Nickelback’s front man, Chad Kroeger, has never been known for his political outspokenness. But that night, he made a speech: For 20 years, he said, “they’ve been trying to cancel us.”