It has been almost four years since Japanese e-commerce giant Rakuten signed on to become Tokyo Fashion Week’s title sponsor but organisers believe the partnership has only now reached its full potential.

The latest edition of the event in March was an opportunity to recover some of the momentum lost during three years of pandemic disruptions. Rakuten’s ‘By R’ programme, which formed in 2020 to lure back Japanese designers who had decamped to overseas fashion weeks, supported the Autumn/Winter 2023 season shows of Chika Kisada and Takahiro Miyashita’s The Soloist. The latter also worked with Rakuten in hosting a shoppable pop-up with nine other brands.

While most Japanese fashion companies are now returning to business-as-usual — including brick-and-mortar stores reliant on big-spending tourists like the Chinese who are back in droves — businesses like Rakuten find themselves navigating a market that has finally changed. The pandemic-induced surge in e-commerce that was felt everywhere was even more pronounced in Japan, a long-time digital laggard compared to other mature markets.

Between 2019 and 2021, Japan’s fashion e-commerce market grew 27 percent, rising to 2.4 trillion yen ($18 billion), according to Koyu Asanuma, a channel partner overseeing the Japanese market for trend forecaster WGSN. The broader e-commerce industry grew 30 percent during the same period, according to data from Japan’s Ministry of Internal Affairs and Communication.

Although Japan’s overall e-commerce market has already peaked — data from Nint analysed by Nikkei Asia found that it levelled off in mid-2022 — experts suggest that companies will be able to get more mileage out of the luxury segment.

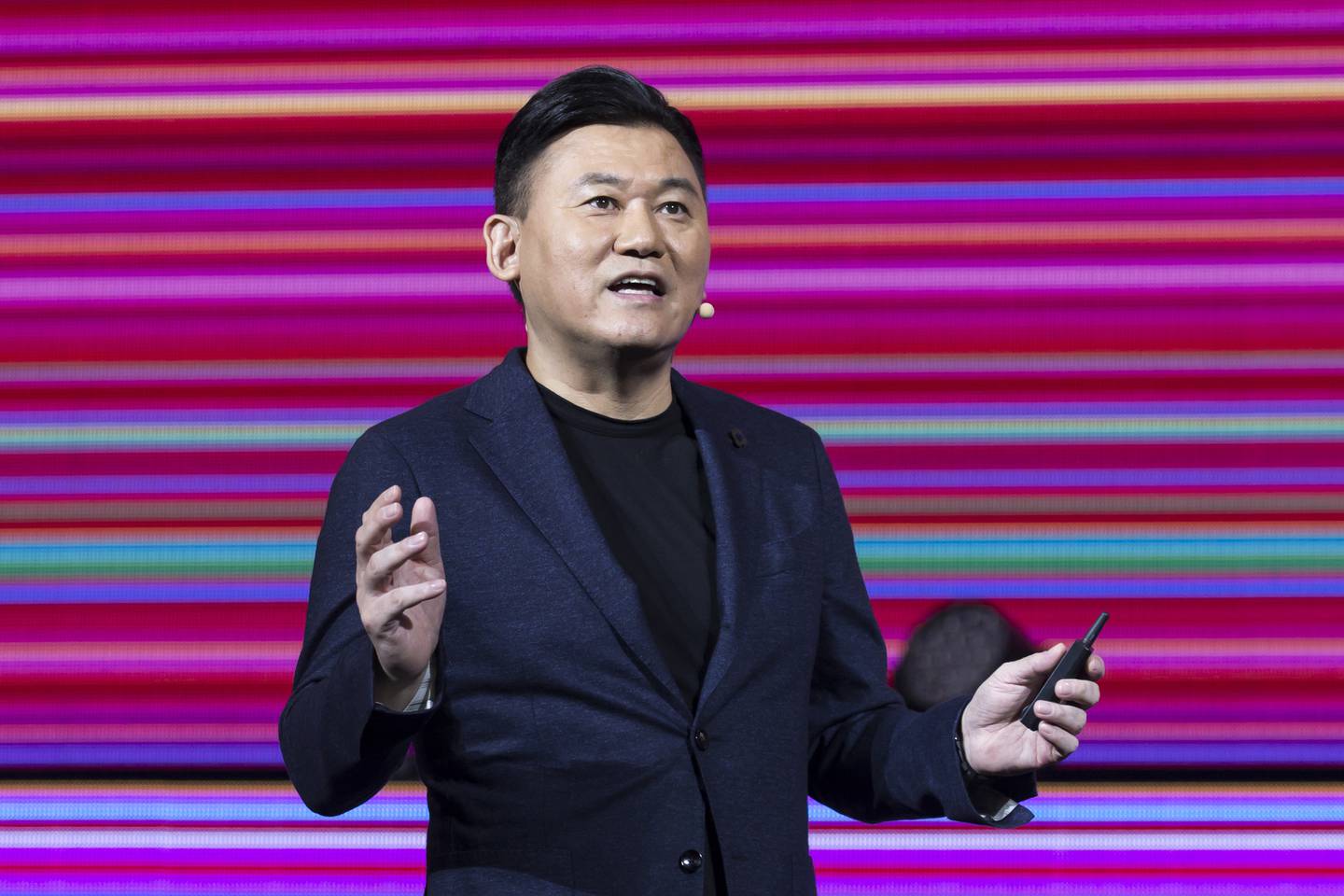

“Five years ago, we weren’t having intense discussions about luxury fashion e-commerce,” said Ryo Matsumura, Rakuten’s group managing executive officer and deputy vice president of marketplace. “But behaviour has changed. People are exploring and seeking out items digitally.”

The shift was confirmed by a survey conducted last year by McKinsey which found that 41 percent of Japanese luxury consumers are researching and purchasing across channels including digital ones, rather than heading straight to department stores and boutiques.

Rakuten, like its arch-rival Amazon Japan, sells everything from electronics and homewares to clothing. But one of the things that sets them apart is that the former has been vigorously pursuing luxury brands in recent years and managed to sign several high-profile names to its dedicated fashion sub-platform.

Today, Rakuten manages e-commerce storefronts for the likes of Maison Margiela, Marc Jacobs, Missoni and Chloé, alongside niche labels like JW Anderson, Anrealage and White Mountaineering, as well as private label collections from popular Japanese multi-brand retailers Beams and United Arrows.

Though most of the biggest global brands’ limit their offering to accessories, their mere presence on the platform underscores how far the roster has come since Rakuten was home to exclusively mass-market labels like Gap.

A Race for the Premium Space

Rakuten’s main rival in the upmarket fashion e-commerce race is Zozo, which also set up a dedicated luxury portal during the pandemic, securing several brand partnerships. Launched in early 2021, Zozo’s Zozovilla sits as a section within Zozotown, its main branded marketplace spanning fashion and beauty.

It was Kotaro Sawada, Zozo’s chief executive who took the reins from the company’s charismatic founder Yusaku Maezawa in 2019, who laid the groundwork for Zozovilla. Currently, the platform sells dozens of high-profile international brands, from Marni and Loewe to Dries Van Noten and Comme des Garçons. Like Rakuten, its offering skews heavily toward accessories.

So far, it looks like a tight race between the two companies. Last year, gross merchandise volume across Rakuten’s fashion business (including, but not limited to luxury) hit 1 trillion yen ($7.4 billion), marking 10 percent growth year-on-year. For the third quarter of Zozo’s 2022 fiscal year, the fashion-focused e-tailer’s GMV reached 406 billion yen ($3 billion), an 8.3 increase year-on-year. Extrapolating that over a full year and stripping out revenue from services brings it roughly in line with Rakuten.

Zozo, which counts Yahoo Shopping and messaging super-app Line as sister companies, is betting on its fit technologies like the Zozosuit (clothing), Zozomat (shoes) and Zozoglass (cosmetics) to help it iron out friction in the buying journey. Crucially, it has a younger slant: the company says the bulk of its 10 million users are Gen Z and Millennials.

“What’s very important is constant newness, to keep on bringing new collaborations, new content, new news, different ways to style… especially for Gen-Zs,” Zozo’s executive officer Christine Edman, told BoF earlier this year.

Zozo’s focus on the fashion segment might give it an edge in some areas but Rakuten’s fashion week investment has upped its luxury credentials and helped attract industry leaders overseas where it needs to create goodwill among decision-makers to secure more brands. “We saw many global buyers and editors return to Japan [this latest season at Rakuten Fashion Week Tokyo],” confirmed Hiroshi Komoda , senior director of the Japan Fashion Week Organization.

In the seasons ahead, the company plans on taking its activations to the next level by collaborating with the ‘big four’ fashion weeks in Europe and the US to bring Japanese designers abroad, and foreign brands to Tokyo. Its parent, Rakuten Group, also boasts an arsenal of businesses beyond e-commerce including fintech and mobile communications, which Matsumura believes it can leverage to improve customer experience.

The fate of Japanese e-tailers is important to global brands because digital channels have a growing role to play in what remains one of the world’s largest, most mature, and dynamic luxury markets.

Consultancy Bain estimates that sales of luxury goods in Japan are worth some €24 billion (around $26.3 billion) this year, which amounts to half the value of all other countries combined in the Asia region, except China. Japan has more than recovered to pre-pandemic levels, having grown around 1 percent between 2019 and 2022.

The outlook for Japan’s luxury market is also positive. Consultancy McKinsey expects it to grow by around 4 percent through 2025. And despite the much-needed boost that the return of mainland Chinese tourists will bring this year and beyond, the firm predicts that the growth will be driven mainly by domestic, rather than foreign, shoppers.

Foreign and Local Contenders

Alongside domestic marketplaces, Japan’s fashion-forward shoppers head to foreign luxury e-tailers like Farfetch and Net-a-Porter to buy whatever designer brands they can’t access through physical retail. Most established global names (from Ssense to streetwear-focused End) ship to the country in an effort to tap local luxury demand. But the barriers to purchasing from overseas platforms are high, says WGSN’s Asanuma.

“Once Japanese people feel like the localisation is off — for example, if the language translation isn’t as natural as they’d expect — their motivation goes down.”

That trust factor is also the reason that Japan’s troubled but beloved department stores, which were especially reluctant to embrace online sales before Covid, shouldn’t be underestimated as omnichannel purchasing journeys now thrive. “The security is really trusted [for department stores] in terms of customer service and after-sales service, whereas Rakuten and Zozo are stronger in mass and medium-priced markets,” Asanuma noted.

Most of the top department groups selling luxury goods in the country — including Isetan Mitsukoshi, Daimaru Matsuzakaya, Takashimaya and Hankyu Hanshin — have ramped up efforts to digitise since the pandemic, but some have done more than others. After launching a shopping app in November 2020 to connect homebound shoppers with sales assistants, Isetan is among those with a fully-fledged international e-commerce service.

Asanuma notes that both global luxury brands and Japanese consumers are often still loyal to the department stores that have served them for generations. But that loyalty is tested when their offering doesn’t live up to customers’ expectations.

Isetan’s online platform, like Daimaru’s, is more geared towards lifestyle categories and mid-market fashion than luxury, despite the prominence of high-end brands in their physical stores. To truly benefit from the growth of the local luxury market and stave off a slowdown, these offline legacy players will have to look beyond their current core of loyal but older shoppers.

The Rise of Niche Players and Specialists

Having worked hard on growing their e-commerce business before the pandemic hit, a few multi-brand boutiques are now reaping the rewards instead of playing catch-up.

Take Restir, the high-end Tokyo boutique selling big international brands like Balenciaga, Valentino and Raf Simons alongside up-and-coming names such as Marine Serre and Simone Rocha. During the first half of the current financial year, which ended in January, sales were up by almost 100 percent from 2019, says the retailer’s creative director Maiko Shibata.

Interestingly, much of this growth was driven by international sales of Japanese brands like Sacai, Maison Mihara Yasuhiro and Saint Mxxxxxx since Restir offers navigation in English and express worldwide delivery. “Our online shopper is different from the offline customer,” Shibata wrote in an email, noting that overall sales to foreign customers are five times what they were pre-pandemic.

Foreign demand for Japanese luxury isn’t the only gap in the market that smaller e-commerce players are capitalising on. In 2019, Nanae Matsuoka went from working on digital marketing for a French luxury brand to founding SixtyPercent, an e-commerce platform selling Asian fashion brands to young Japanese shoppers. South Korean brands are proving especially popular.

McKinsey anticipates that Japan’s luxury rebound will be driven by younger and wealthier locals, but Matsuoka thinks it will be challenging to capture that audience as most local luxury e-tailers are still “lost” when it comes to Gen-Z.

“There are so many [knowledge] gaps when it comes to e-commerce: [even the biggest] Japanese platforms don’t really care about social media,” she said, adding that one reason SixtyPercent has grown so fast is because it is well-integrated with younger shoppers’ favourite social platforms.

It’s also impossible to ignore the impact of the country’s famously bureaucratic corporate culture, which Matsuoka has witnessed first-hand, on e-commerce innovation. Even as consumers’ uptake of online shopping raced ahead, “it’s hard for a [fashion retailer] that’s 40 years old to change their culture in two years,” she said. “Leaders who are 40, 50 years old [here] don’t even know how to deal with TikTok.”

In a country where physical retail has long had a firm grip on luxury sales, it’s no surprise that the online purchasing journey isn’t yet optimised — or as advanced as its nearest neighbours.

Despite the progress seen in Japan’s luxury e-commerce market, it is still in its early days when compared to the likes of China and South Korea. For optimists, this means room for growth. But now that the pandemic-induced boom has passed, online retailers in Japan will need to work harder to encourage more affluent customers to buy online — and to choose them over their rivals.