This is an edition of the revamped Books Briefing, our editors’ weekly guide to the best in books. Sign up for it here.

I love music, but I never learned to play an instrument (something I still occasionally blame my parents for—though, as a father myself, I should know better). The mechanics and language of music are a blind spot for me—a deficiency I was reminded about as I tried to edit a recent essay from Anthony Tommasini, the former chief classical-music critic for The New York Times. Tommasini reviewed a new book about the composer Arnold Schoenberg, whose early-20th-century experiments in music were akin to Pablo Picasso’s in painting and James Joyce’s in fiction. But Schoenberg’s work—and the other envelope-pushing music it inspired—has not found the same sustained interest and acclaim as Picasso’s and Joyce’s. In fact, his music is often categorized as challenging or even infuriating. Tommasini makes a wonderful case for Schoenberg and his continued relevance. But in order to understand his argument and Schoenberg’s innovations, I needed to appreciate the difference between tonal and atonal music—music, as Tommasini put it in the essay, “that didn’t revolve around one key but gave equal weight to all 12 notes.” I could recognize the resulting dissonance when I heard it, but I couldn’t really explain what produced it. Tommasini’s patience with me made me think that he would be a great guide in helping me advance my own music education. So we had a brief chat full of recommendations for further reading and listening.

First, here are four new stories from The Atlantic’s Books section:

Gal Beckerman: For readers like me who want to better understand how classical music works—say, the difference between tonal and atonal music—what’s the most accessible way to do this?

Anthony Tommasini: You know, I try to avoid talking about classical music as if there’s this huge difference between tonal and atonal music, since those languages overlap all the time. I find a better way to help newcomers understand how music works is to look at structure, the use of materials (themes and such). For this, pieces written as variations on a theme are ideal. Listen to Brahms’s exhilarating piano piece “Variations and Fugue on a Theme by Handel.” You can really follow how inventively Brahms takes the joyous, bouncy theme and finds all kinds of ways to vary it. Leon Fleisher’s early 1957 recording is terrific. Then, for something flinty, jagged, rigorous, and shockingly modern, listen to Copland’s arresting 1930 “Piano Variations.” If you can just go along with all the bracing dissonance, you’ll “get,” I bet, how ingeniously Copland keeps manipulating a stark, punched-out theme.

Beckerman: How about compelling biographies of composers? And I should mention here your own recent book, The Indispensable Composers, which is your guide to the canon.

Tommasini: There are many engrossing biographies of composers—for one, the great scholar Alan Walker’s authoritative, historically rich 2018 bio of Chopin. For another kind of biography that I found fascinating, there’s the British conductor Jane Glover’s Mozart’s Women: His Family, His Friends, His Music. Glover looks at Mozart through the women who nurtured, fascinated, charmed, amused, and loved (or didn’t love) him—not just his mother, his prodigiously talented older sister, and his lively and devoted wife but the singers who created roles in his operas—even those female characters, who were Mozart’s women too!

Beckerman: I was also thinking about books that use classical music to illuminate a certain historical period (like Jeremy Eichler’s recent Time’s Echo, about composers working in the shadow of the Holocaust). Any of these that come to mind?

Tommasini: Yes, my friend Jeremy’s Time’s Echo is an impressive achievement, and I’m pleased with the excellent reception it’s getting. And the whole point of my friend Alex Ross’s acclaimed The Rest Is Noise was to tell the story of the 20th century through its music. The subtitle says it all: Listening to the Twentieth Century.

Beckerman: And finally, what about novels? It’s always interesting when one art form tries to capture the magic of another. Are there any that could help a reader understand what making music feels like?

Tommasini: Novels? Nothing leaps to mind. I think novelists may realize how hard it is to describe music—to describe sounds—with words. That’s what critics are expected to do, and let me tell you, it’s not easy. But poets? That’s different. I loved the British poet Ruth Padel’s 2020 collection Beethoven Variations: Poems on a Life. Drawing from her knowledge of music history and her experience as an amateur violist, she digs deep into mysteries about the composer’s life and music, including the most unfathomable: What did it feel like to go deaf? What did music sound like to him? In one early poem, “If Your Father Damaged You,” about the abuse the young Beethoven took from his bullying father, she writes, “Your response to challenge ever after will be attack. / You will need no one. Only the relationship / of sound and key. You improvise.”

The Case for Challenging Music

What to Read

Free Food for Millionaires, by Min Jin Lee

Lee’s first novel opens with a warning: “Competence can be a curse.” The warned is Casey Han, a recent Princeton graduate. Her parents, who emigrated from Korea and manage a Manhattan dry cleaner, urge Casey to pursue a steady job in a field like law or medicine. But she covets a different kind of American dream: “a bright, glittering life” of luxury goods. Taking a summer internship at an investment-banking firm, she navigates its grueling hours and cutthroat competition very capably. But she carries the constant anxiety of trying to keep up with her primarily white peers, who come from money and live a lifestyle she can’t afford. In her single-minded pursuit of wealth, she also manages to alienate her parents, her mentor, and her partner, and must confront whether the class mobility is worth the price. The dream of affluence lures Casey into its orbit but never quite admits her. Despite the supposed meritocracy at work, grit and determination are not enough. —Tajja Isen

From our list: What to read when you’re feeling ambitious

Out Next Week

📚 The Book at War, by Andrew Pettegree

📚 Songs on Endless Repeat: Essays and Outtakes, by Anthony Veasna So

📚 Everywhere an Oink Oink: An Embittered, Dyspeptic, and Accurate Report of Forty Years in Hollywood, by David Mamet

Your Weekend Read

Why America Abandoned the Greatest Economy in History

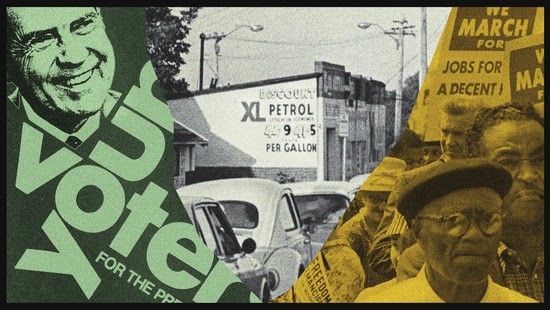

Since 2016, policy makers, scholars, and journalists have been scrambling to make sense of the rise of Donald Trump—who declared, in 2015, “The American dream is dead”—and the seething discontent in American life. Three main theories have emerged, each with its own account of how we got here and what it might take to change course. One theory holds that the story is fundamentally about the white backlash to civil-rights legislation. Another pins more blame on the Democratic Party’s cultural elitism. And the third focuses on the role of global crises beyond any political party’s control. Each theory is incomplete on its own. Taken together, they go a long way toward making sense of the political and economic uncertainty we’re living through.

When you buy a book using a link in this newsletter, we receive a commission. Thank you for supporting The Atlantic.