The Jevons paradox still has much to teach us.

After a brutal 2023, the vibes around self-driving cars are improving. Cruise, the industry leader whose vehicle was involved in a horrific San Francisco crash last fall, has rebooted under new management, while rival Waymo is expanding to serve broader swaths of the Bay Area and Los Angeles and Tesla is promising a new robotaxi service.

Although Americans say they remain wary of autonomous driving, boosters insist there is nothing to fear. In fact, they foresee roads full of self-driving cars that are both safer and cleaner than the status quo, a tantalizing prospect in a country where transportation is the largest source of greenhouse gas emissions and residents are several times more likely to die in a crash than those living in other rich nations.

Enticing though they are, such arguments conceal a logical flaw. As a classic 19th-century theory known as a Jevons paradox explains, even if autonomous vehicles eventually work perfectly — an enormous “if” — they are likely to increase total emissions and crash deaths, simply because people will use them so much.

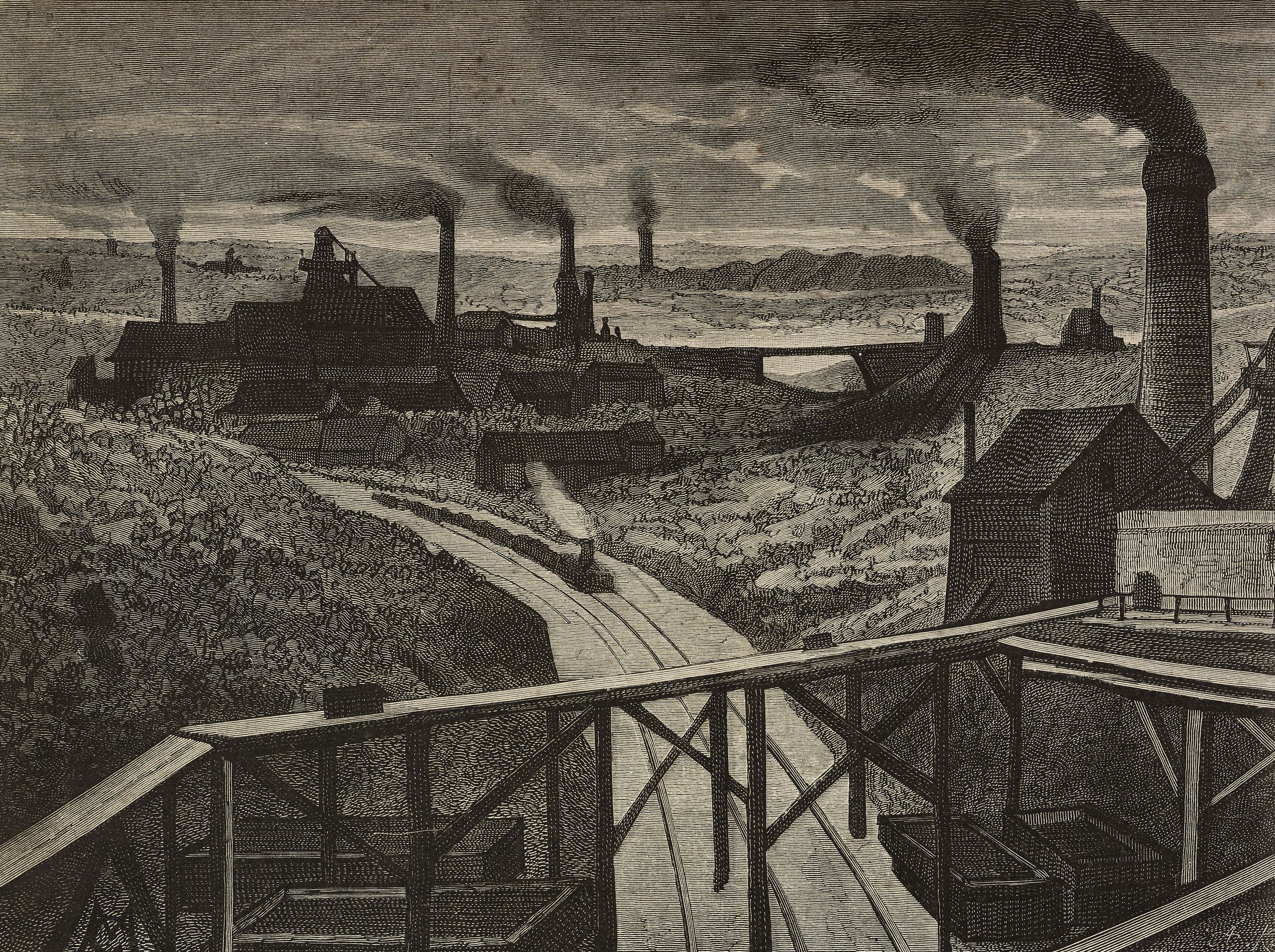

In the 1800s, coal was the sine qua non of economic development, essential for everything from heating to transport to manufacturing. In Britain, the country where the stuff first powered an industrial revolution, national leaders debated how concerned they should be about potentially depleting coal deposits. Some argued that supply would never be exhausted because improvements in steam engine designs would steadily reduce the amount of coal necessary to power a train, make a dress, or do anything else. Productivity gains would allow Britain’s coal resources to stretch further and further.

In his 1865 book The Coal Question, the economist William Stanley Jevons explained why he disagreed. Jevons drew from then-recent history to show that steam engines’ efficiency had led people to deploy more of them. “Burning coal became an economically viable thing to do, so demand exploded,” said Kenneth Gillingham, a professor of environmental and energy economics at Yale. “You have steam engines everywhere, and people are using them instead of water power. You actually use a lot more coal than you did initially.” Despite the improvements in steam engine design, Jevons argued, total coal use would continue to rise.

Today, the Jevons paradox describes a situation where greater efficiency in deploying a resource (such as water, gasoline, or electricity) causes demand for that resource to skyrocket — negating an expected decline in total usage. Electric lights are often cited as an example: people have responded to improved light bulb efficiency by installing so many more of them that there has been no decline in the total energy consumed by lighting. The Jevons paradox has become a bedrock principle of environmental economics, used to explain why efficiency improvements can backfire and cause the opposite outcome from what was intended.

Its lessons can also illuminate transportation. Consider the projects undertaken by highway agencies to alleviate roadway congestion. Public officials often justify them by noting (accurately) that gas-powered engines are less efficient and release more pollutants if they are stuck in gridlock instead of moving at a steady clip. For that reason, they argue, highway expansions or traffic technologies that mitigate traffic jams will also reduce emissions.

The Jevons paradox reveals a blind spot in such claims. If an added lane or new traffic technology does relieve congestion, more people will decide to drive due to a drop in the “cost” of using a car — in this case, the time sitting in traffic. Even if each car now produces fewer emissions due to faster travel speeds, these benefits could be overshadowed by the sheer number of new trips that would not have otherwise occurred. In other words: backfire. (The benefits of expanded highways are even more questionable when one considers the likelihood that rising car volumes ultimately force traffic to move as slowly as before — only now with more cars belching fumes as they inch forward. This phenomenon is known as induced demand.)

Now consider the case of autonomous vehicles. Seeking to win over skeptical regulators and members of the public, AV supporters frequently cite the supposed safety benefits from replacing the fallible humans sitting behind the wheel with technology that will never drive drunk, high, or distracted. Some also suggest that self-driving cars will reduce energy use and emissions since they will avoid the quirks of human driving that compromise engine efficiency. “The higher the proportion of AVs on the road, the smoother the overall flow of traffic ought to be, resulting in less energy-consuming stop-and-go traffic,” predicted a 2021 blog post from Mobileye, a technology company that claims it is “driving the autonomous vehicle evolution.”

Both of these supposed benefits are dubious; AVs’ computers may make driving errors that humans would not, and even if they run entirely on electricity, their software, hardware, and sensors require an enormous amount of power that generates its own emissions as it is produced. Still, it is reasonable to expect AVs’ reliability and efficiency to improve over time. For the sake of argument, let’s take a leap of faith and assume that an average self-driving car will eventually be both safer and cleaner than one driven by a human. Will total crash deaths and emissions then fall?

The Jevons paradox suggests we shouldn’t count on it.

As AV companies’ ads show, the raison d’être of autonomous vehicles is making driving easier and more pleasant, with passengers free to hold a work meeting, sing a song, or grab some shuteye. How do people respond when an activity becomes less onerous and more fun? They do more of it.

Similar to highway expansion, the availability of autonomous vehicles will likely lead people to take longer motor vehicle trips or opt for a car when they would have otherwise used transit, biked, or stayed home. The result will be a lot more (now autonomous) cars on the road. As the University of Virginia historian Peter Norton wrote in a prescient 2014 article, self-driving technology could lead people to “spend more total time in vehicles [and] use them for even more tasks.”

Norton, who teaches the Jevons paradox in his classes, told me that he wrote that article because he “was seeing smart engineers argue, to my utter astonishment, that [AVs’] efficiency against would only bring savings — with no counteracting costs. How they can continually deny this elementary fact is beyond me.”

Supporting his point, a recent paper from the Transportation Research Board concluded that “the likelihood of making additional trips increases” when autonomous vehicles are available, even if they are shared instead of owned. Since each self-driven mile creates some pollution and carries some risk of a crash death, the rise in total driving will counteract the theoretical climate or safety improvements over a single, otherwise identical human-driven journey.

The societal impact of self-driving cars looks even worse when considering second-order effects related to land use. Just as the ascent of car ownership fueled suburbanization in the 20th century, AVs could lead people to relocate to larger, less energy-efficient homes on the urban fringe, where car trips — now more tolerable — are longer.

At the moment, there are more questions than answers about the collective effects of AVs, which are currently available in only a handful of US cities. As self-driving companies pour billions of dollars into advancing their technology, it is impossible to know how safe and energy-efficient their products could eventually become. But the Jevons paradox suggests those are not the only questions to consider. Another, equally crucial one: how much more driving will AVs induce — and will those added miles swamp any possible upside?