The comments from the leading Fed officials were the latest evidence of the central bank’s growing attention to persistent inequality in the economy — a gap that appears to be widening during the coronavirus pandemic. Black and Hispanic workers have been hit harder by the economic fallout from the Covid-19 lockdown than white workers.

The Fed itself has faced criticism for inadvertently exacerbating inequality because its emergency policies are designed to backstop financial markets and allow companies to borrow money. That has boosted the stock market, most of whose value is owned by the wealthiest Americans, even as some major companies have continued to lay off workers. Just 1.2 percent of the value of stocks is held by Black families and 0.5 percent by Hispanic families, according to quarterly Fed data.

The central bank officials Wednesday said that now is the time to face uncomfortable questions about race and the economy.

“First, we have to listen more,” Rosengren said. “This is an attempt to be listening more.”

They said that while the Fed has limited capabilities to intervene in targeted areas of the economy with monetary policy — it can’t provide grants or unemployment benefits like Congress — it does wield regulations, data and influence with other policymakers. Fed Chair Jerome Powell has repeatedly called on Congress to deliver more emergency aid to the most vulnerable Americans, including in a speech on Tuesday.

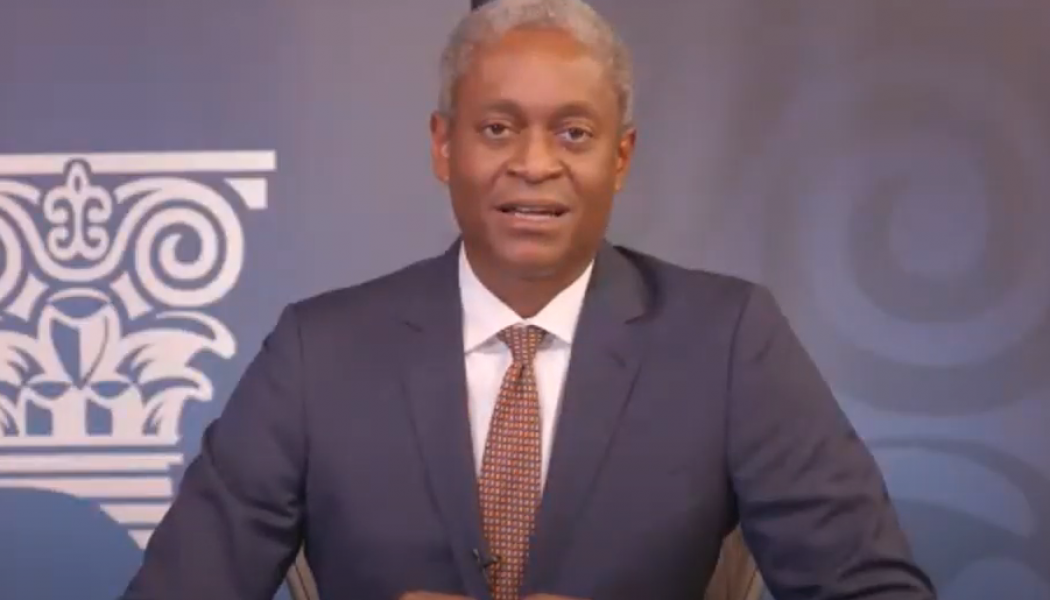

Bostic said it was important for the Fed to signal with its actions that it represents all Americans.

“We’ve got to think about how do we lean in to a number of areas that we may not actually have the specific authorities or policies that drive it, but we have information, we have ways of thinking about it that are important,” said Bostic, whose name has been floated as a potential appointee in a Joe Biden administration.

Among the ideas Bostic proposed were revamping the landmark anti-redlining law known as the Community Reinvestment Act to provide incentives for banks to invest in places of need in a more creative way.

Kashkari, who described steps he had taken to improve diversity inside Minneapolis Fed, said another way to address the problem was by forcing the Fed to pay closer attention to workers.

One option Kashkari said he was discussing with his staff was how to give workers and diverse communities a bigger voice in his bank’s contribution to the Fed’s “Beige Book” reports that describe economic conditions throughout the country.

“Why is it that business has a louder voice historically in the Federal Reserve?” he said.

Kashkari said he had observed a big disconnect between how business viewed the labor market and workers viewed the labor market.

“Frankly, business had it wrong. Business kept saying, we can’t find workers,” he said. “And it was nonsense. The workers were out there.”