This article originally appeared in the July 1992 issue of SPIN. In honor of Achtung Baby turning 30, we’re republishing it here.

“What you can never get in your book is the utter, total boredom of being in a band [on tour].” —John Lydon, quoted in Jon Savage’s England’s Dreaming

April 9, 1992: Rolling through the sun-scrubbed Arizona landscape on the way to Tucson. Last night was, I think, Austin. Axl Rose was at the show, I guess he wanted to hang out with rock stars who are even shorter than him. Strange that the desert really does look like a Roadrunner cartoon; except in real life, the rock-infested hills are less friendly, looming like scars carved from the unrealistically blue sky. Antitank fighter planes swoop low over the cactus, looking, we hope, for someone else.

Slumped in the front seat of my Ford Aerostar minivan, I stare out the window at the occasional patches of yellow poppies. The vista speeding past, I’m thinking, closely parallels my impressions of U2 on this tour: big, romantic. Beautiful. Overwhelming. Remote. Untouchable. And, finally, empty.

Zoo TV is an Important Event not just because it’s the first tour in several years by one of the biz’s biggest, but because it represents a further step in the evolution of rock music as spectacle. This is hardly news—it’s been going on at least since Led Zeppelin, and probably further back in the Dark Ages of rock—but U2 came out of a supposed reaction to the pomp and circumstance of ’70s prog overkill. And despite indications of advanced pomposity as early on as 1984’s The Unforgettable Fire (most pronounced, of course, on the band’s 1988 concert movie ego-fest Rattle and Hum), U2 has rarely let the event overshadow the music. That’s not the case with this tour.

Which is one reason I like Zoo TV so much—it renders not only the performance secondary, but the performers as well. Wander through the backstage hubbub and you can’t help but feel that the four band members are little more than accessories to the massive, and massively detailed, production. U2 whisks in and out of the various venues in a stream of white limos to the two chartered MGM Grand jets waiting at the airport, spending no more time in the dressing room or elsewhere than is absolutely necessary. The more they hang out, the more they get in the way of the real work.

The Zoo TV crew, by my less than scientifically precise count, numbers at least 100—halfway through the tour, crew members were still introducing themselves to each other, or running into old friends (“You’re on this tour, too?”). It takes this crew approximately 12 hours to set up the stage, so if the next show is the next night, a separate crew is already at work in the next town, setting up a duplicate set of rigging at 3:00 a.m. while the crew in the previous town is engaged in packing it away. There’s very little margin for error, despite which, in the month and a half I tagged along behind the tour, no show went on more than 15 minutes late, with one exception.

It’s even more impressive considering that a good portion of that 100-person crew is comprised of management, accountants, publicists, private security, wardrobe staff, caterers, drivers, and so on. All these are honey-combed in as many makeshift offices as a given venue will have space for.

Here’s the real zoo: laminate-bearing henchmen and women, walkie-talkies strapped to their sides, power-walking with tight, urgent faces down endless corridors; phones constantly gurgling; tattooed strongmen barking incomprehensible Irish orders; wheeled crates full of unidentifiable but doubtless phenomenally costly equipment hurtling down corridors; strange wispy men in capes. I have no idea what any of these people do. (Is that Kafkaesque or Felliniesque? I can’t remember.) Compared to this maelstrom, the show itself is almost anticlimactic.

Resulting perhaps partly from the behind-the-scenes anarchy, certain weird hierarchical inconsistencies crop up backstage. Little things, mainly, most of which aren’t probably even under the purview of the band members themselves, but they look to me like clues. For instance: Even though the Pixies have been handpicked as opening band for the first leg of the North American tour (the Edge and Bono are reportedly big fans), U2, which has gone to the trouble of printing up signs for just about every conceivable subset of its own organization, can’t manage better than to slap “Support Act” signage on the Pixies’ dressing room.

So yeah, anyway, Zoo TV. During its exhilarating course, I started thinking a lot about how the the sheer weight of accumulated detail involved in mounting a production of this sort left little room for the sort of spontaneity, or at least unpredictability, that, for me at least, defines rock (and that, in the past, helped define U2). The whole process was depressingly rational—and while I can’t help but admire the result, I wonder in this case if the ends justify the means. Which is not so much U2’s fault as that of the machinery that demands of our rock musicians a hugeness that leeches their humanity; and then tears them down when they inevitably fail to live up to the impossible standards we set.

Lakeland/Tampa, Florida, February 29: The 45-minute drive from Tampa, where I’m staying, to the Lakeland Civic Center, past Mango, Thonotossassa, Zephyrhills, innumerable Stuckey’s (“Fresh Fried Chicken and Tater Logs”), and a sign for the Largest Citrus Market in Florida (operated by R. E. “Roy” Parke and Family) brings me to a tangle of crew buses and semis at the rear entrance. It’s the first gig, and apparently no one’s figured out the proper parking order yet. I count 11 semis and 7 crew buses for U2. I wander into the catacombs to the bone-shaking thud of U2’s soundcheck (the band has been there for the better part of a week already, setting up the stage and ironing out the kinks). An awe-inspiring tree of U2 signposts directs passersby in at least ten conflicting directions, depending on where exactly we want to get lost. I wander out to the empty arena because it’s the easiest place to find, and sit down near the stage to watch the soundcheck.

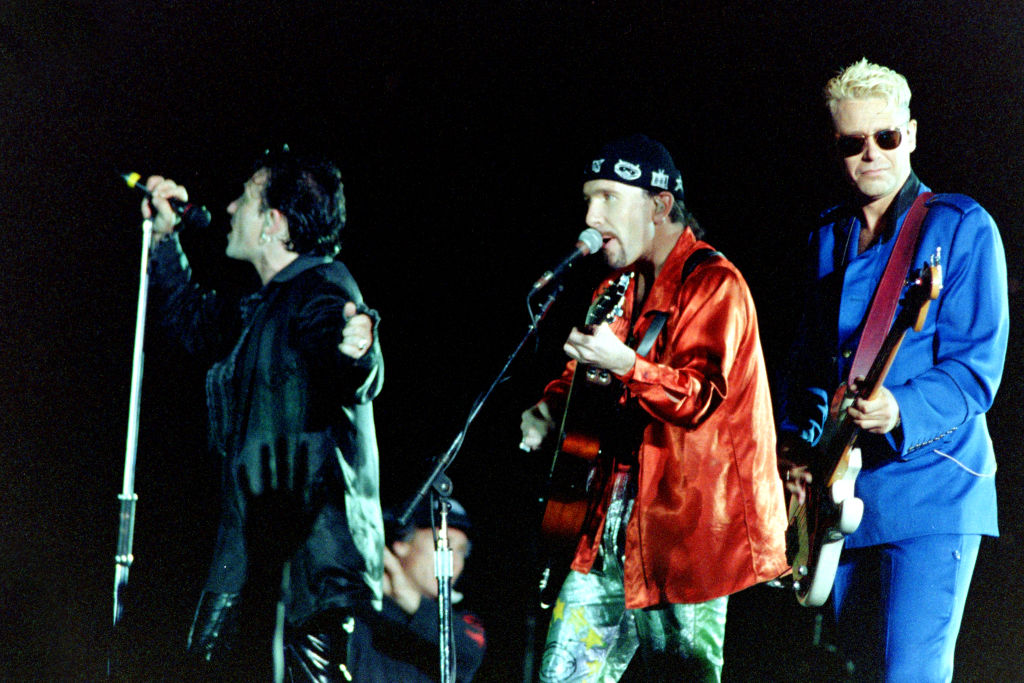

Onstage, the Edge, Adam Clayton, and Larry Mullen, Jr., run through bits of two or three songs. The sound is amazingly pristine even in the vast, echoey hall. Various video monitors flicker on and off as the crew tests this and that gimmick. No sign of Bono though—and then, suddenly, the arena fills with his unmistakable vox, riding easily over the top of his bandmates’ accompaniment. I finally spot a diminutive figure standing out by the soundboard, arms crossed, watching the band onstage. He’s not holding a microphone, he’s wearing it, in his hat. Cool—it’s the first time I’ve seen someone use a headset mike in a non-dork manner.

During U2’s show later that night, kids who manage to stretch far enough to press Bono’s flesh react as though touched by the hand of God—U2’s audience, at least the most frenetic part, is here not to praise but to bury with worship. His every gesture, no matter how small, provokes them to a near-religious frenzy out of all proportion to what’s actually going on, musically. Bono exaggerates his rock star-ness, plays with the stage set’s toys (rock-star trappings), stretching his persona to the point where his ego actually ceases to matter; he inflates it until it bursts, and he becomes as egoless as he’s ever wanted you to believe. There’s a real strong sense of the ridiculous about the process, which is all the more endearing even though you know that they know that you know . . . oh, hell, I don’t know.

It’s just great, that’s all. But, as great as it is, it has nothing to do with my idea of rock ‘n’ roll. Closer comparisons—and this is true of arena rock in general, but is made especially apparent on the Zoo TV tour because of its emphasis on spectacle and because of the unusual intensity of the band’s die-hard devotees—would be with mass religious ceremonies or Monster Truck shows. This is the circus part of “bread and circuses,” which in a recession-fraught year somehow makes perfect sense, and even helps.

Back in Tampa, me and my babe saunter down to the Holiday Inn lounge (“The Casbah”) for a nightcap. It’s close to midnight, and few patrons occupy the tables. Suddenly, halfway through our first Bailey’s Irish Cream, the stage-lights (we hadn’t even noticed the stage) come up to reveal For Your Eyes, a synth-only male-female lounge duo whose eerily on covers of Toto’s “Hold the Line” and Journey’s “Any Way You Want It” are accentuated by dim, pulsing lights that make the two members look, I swear, like boy and girl versions of that android guy on Star Trek: The Next Generation. Their stage patter is cheerful and awkward, although they have to spend an inordinate amount of time fending off drunken Metallica requests from recent Rush concert returnees (that show, on the same night, drew over 12,000 to Zoo TV’s 7,000 and received almost no press coverage). Everything about their performance makes me distinctly uncomfortable; the tension between the band and the Rush rowdies makes me cringe. For a few minutes, it seems like anything could happen. Now this is more like it.

Atlanta, Georgia, March 5: Even though my backstage laminate reads “All Access,” I can’t so much as walk by U2’s dressing room without being accosted by one of the two sets of security guards (venue security, which changes nightly, and U2 private security, who travel with the band). They keep a blue curtain drawn in front of the dressing room door, for obscure, though doubtless occult-related reasons. Curtains are big on the Zoo TV tour; there’s a curtained room just offstage where Bono runs to change costumes mid-set (a girl waits there whose only apparent job is to hold the mirror for him), and there’s a closely-curtained pit below the stage where they keep some guy surrounded by strange-looking electronics.

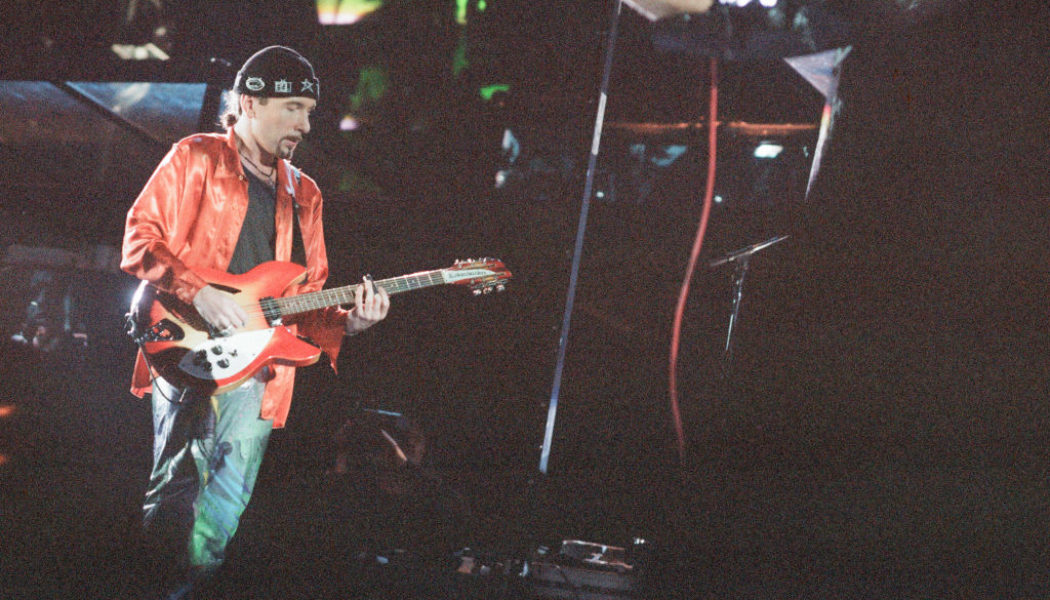

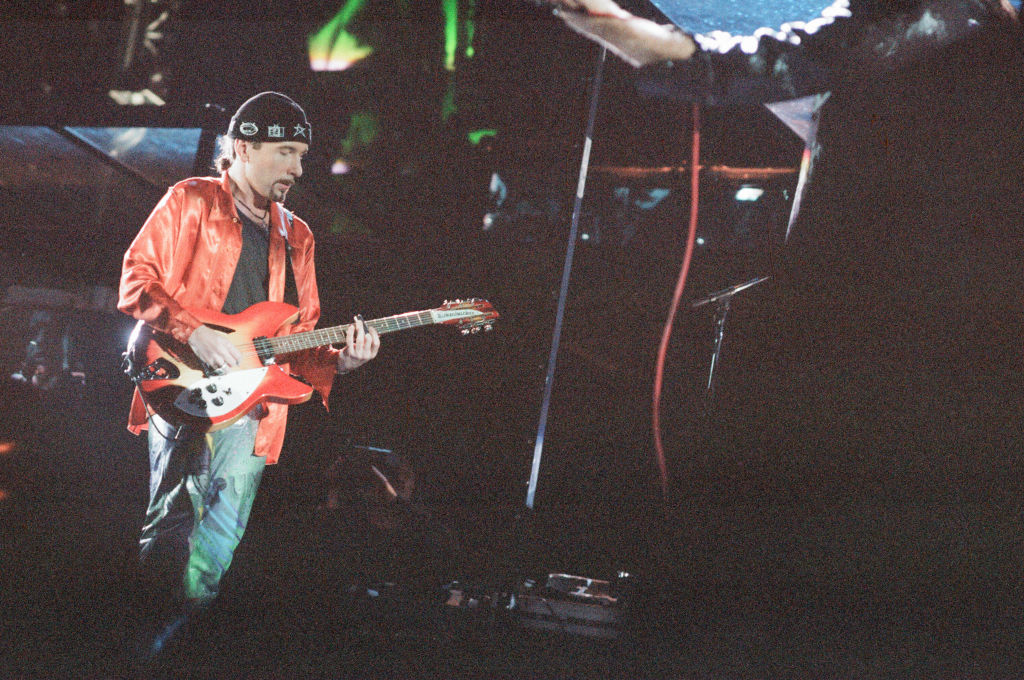

One thing I miss on the Zoo TV show is the way U2 used to be able to stretch out and improvise in the middle of its songs and sets. There’s little room for surprises on this tour—the set list is so firmly established that it’s printed on the back of some of the crew laminates, right down to the encores. It has to be: The stunning video accompaniment is keyed to a specific song length. Also, despite what the Edge implied when he cohosted MTV’s 120 Minutes (to the effect that the band decided on this tour to play only what the four band members can actually produce live, necessitating the Edge’s fearsome array of guitar effects pedals), my ear detects a fair amount of sequencer and additional keyboard accompaniment on many of the songs. Why else does Larry the drummer wear headphones, if not to listen to the click track? And what exactly does that little man who sits in the closely-curtained pit surrounded by machines that look an awful lot like sequencers and keyboards do, if not provide keyboard and sequencer accompaniment? Huh?

Improvisation is thus limited to nonmusical aspects of the show, such as who Bono calls up on the phone, or what channels he switches to on the banks of video monitors.

After the show, we drive through the rainy Georgian night to Virginia, past a giant statue of a peach (“Take Exit 92 to view peach”) and a tumbledown shack (“the Alamo”) that sells something called “fatback” and advertises steaks and dancing. Which is all, really, anyone could ask for. Profound road-related observation: No matter how fast you go, someone always wants to go faster.

Philadelphia, Pennsylvania, March 10: Tonight’s concert left me feeling kind of dry. We search for a bar in Chinatown near the hotel, but it’s Sunday night and almost everything is closed. Almost—Saigon Plaza, a pleasant Vietnamese joint, is having karaoke. We wander in, the only two non-Viets, and are presented with a thick binder of xeroxed pages listing roughly a billion possible songs, mostly in Vietnamese. There are a few English titles, too, though the closest they get to rock is Procol Harum’s “A Whiter Shade of Pale.”

Most of the participants choose unintelligible-to-me Vietpop songs, singing more often than not in heart-rendingly beautiful voices, heavily laden with cheesy reverb. Especially the youngsters, of which there are a surprising number for past midnight on a Sunday—one young woman even duets with her baby, to resounding applause from all. Strange form of family entertainment for this late hour. My favorite new Vietnamese pop songs are “I Am the Batman of Love” and “Ultrasong,” both enhanced by their accompanying tacky videos, which look like soft-porn shorts without the flesh.

Strange that it’s easier to hear the out-of-time, Raggedy-Ann heartbeat of rock in a greasy, roach-ridden restaurant than at a, um, rock concert.

Worcester, Massachusetts, March 13: Oh, the ephemeral nature of this business we call show! Last night the U2 concert here at the Centrum was the only thing on the hearts and minds of approximately 13,718 (reserved seating capacity) fans, and this morning, as we prepare to leave for Providence, there’s a baseball-card convention in the very same arena. The circus comes to town, the circus leaves town, and all you’re left with is a ticket stub, a really expensive T-shirt, and maybe an official Achtung Baby condom. (At $3 a pop, no bargain, though the between-sets DJ assures the crowd that they’re sold “at cost.” At cost in Ireland, maybe. They’re a hot-selling item among 12-year-old boys who’re not exactly sure how they work.) And a handful of indelible memories, presumably.

First sign of U2 band members mingling with mortals: back in the crew catering area, the Edge and Adam Clayton sit down for dinner. I wonder if they’re eating meat, as I notice that a fair number of both the U2 and Support Act crews seem to be confirmed vegans. Aggressive health is the new rock ‘n’ roll attitude. Excess is out, man, although Bono reportedly has a weakness for fine champagne (but you wouldn’t, you know, crucify a man for that).

Boston, Massachusetts, March 17: An Irish band playing in Boston on St. Patrick’s Day. Pandemonium outside Boston Garden before the show, green-garbed natives lining the street in front of the Garden with adulatory banners. Recognizing the importance of the occasion, the band actually alters the set tonight to include a couple of traditional Irish numbers (very nicely done), during one of which Bono takes a turn on the congas. Support Act’s bass player reports first contact with a band member. Passing the Edge on the way to the stage, she deliberately catches his eye and says, “Hi!” He replies, “Hi!” smiling.

Afterward, drunks sway through the streets bellowing “rock ‘n’ roll!!” before proudly vomiting in the gutters.

Before the show, we visit the bar that Cheers was modeled after and break into the theme song, which probably only happens there 35 times a day, judging from the world-weary demeanor of the (non-Sam-like) bartender.

Meadowlands/Madison Square Garden, New Jersey/New York, March 19-20: Three consecutive nights of karaoke (it has become an addiction), one in New Jersey where big fat white guys in business suits get up and do Tone Löc’s “Wild Thing” and “Funky Cold Medina,” and two in a bar across from Madison Square Garden in New York. Late on the third night, the gospel group opening for Harry Connick, Jr., treats us to a beautiful impromptu a cappella devotional number.

Celebrity count (actual sightings): In New Jersey, Little Steven (short). At Madison Square Garden, Bruce Springsteen (short), Paul Simon (short), Christie Brinkley (not short).

Toronto, Ontario, March 24: “So Stevie Ray Vaughan goes to heaven,” relates a slightly inebriated concertgoer, in the hotel bar after the show, “where he gets introduced to Jimi Hendrix, and Elvis, and Janis Joplin, and all these really cool rock people, and then he walks by a room where he sees Bono looking intently at himself in a mirror. ‘Hey, wait a minute,’ says Stevie Ray, ‘Bono’s not dead.’ ‘Oh, that’s not Bono,’ Jimi reassures him. ‘That’s God. He thinks He’s Bono.’”

Walking by, I notice that Support Act shares its dressing room tonight with mysterious, self-styled “DJ-guru” BP Fallon, who wears cloaks and vests bearing high-tack paintings of Elvis’ mug, and sits in one of those little Trabant cars between sets playing Led Zeppelin, the Beatles, and Bob Marley and talking about peace—he says “you know” one whole hell of a lot; and Christina the belly dancer, who is both lovely and nice, and furthermore makes her own costumes. The floor is scarred with skate-marks; as with many of the dressing rooms on this mostly-sports-arena tour, this room is usually the provenance of the visiting hockey team.

I spend my time doing some quick calculations, whereby I discover that if Support Act were to scalp its entire daily allotment of U2 tickets at current street prices (anywhere from $150 to $500 a ticket), instead of giving them to friends and VIPs, it would make a lot more money than it gets paid for playing. Doubtless the band is too lazy to take advantage of my revelation—it would probably babble something about “ethics” instead.

U2’s show is so good tonight I nearly start crying. “Somebody has to play rock star,” Bono tells the crowd. “Everybody else is into dance music these days.” Then he launches into their dance hit “Mysterious Ways,” the one that Christina performs on. Just before U2 takes the stage, the crowd does the Wave for about ten minutes, which is fun even though my timing’s a bit off.

Last night in Montreal, Dave Grohl from Nirvana came to say hello to Support Act, of which he’s a major fan, and Larry from U2 made his (and the band’s) only appearance of the tour in the Support Act dressing room. Apparently Dave was a big enough star to warrant his slumming. Later, Dave was also treated to a grandfatherly talk by Bono, who spent an hour lecturing him on the evils of success (“Don’t let it go to your head”) and didn’t take his wraparound fly-shades off the whole time. Dave also revealed Nirvana’s desire to put together a tour playing opposite Lollapalooza this summer in the same cities on the same nights, to be called “Lollapaloser.” Unfortunately, this plan later falls through.

Cleveland, Ohio, March 26: Hate to disagree with John Lydon, but touring, these days, if you’re a big mega-platinum rock star act like U2, is a piece of heavily-frosted cake. Five-star hotels, chartered jets, and fleets of limos certainly help ease the admittedly life-sapping strain of performing and traveling. I drive with my babe to Cleveland. We take the wrong way around (by way of Detroit rather than Buffalo) and I end up wishing we’d flown. Along the way we discuss the mysterious ways of arena rock, specifically whether any amount of success is worth the kind of broad posturing you apparently have to do to reach the spectrum of people an arena act must reach.

“Yeah,” I say, “you couldn’t pay me to get up there and dance like Bono. I admire his courage in doing that.”

“Well, what kind of endears Bono to me,” she remarks, “is that he can’t dance.”

Detroit, Michigan, March 27: Pizza night. Bono tries to order 10,000 pizzas from onstage, manages to come up with a hundred, which they distribute to the crowd. I snag one from the crew by pretending to be in Support Act. “We love the Pixies!” they tell me. “Have a pizza!” Celebrity report: Jack Nicholson, Danny DeVito (in town filming a movie). Nicholson wears a beret, nullifying with one bad haberdashery decision all my respect for him. Unless it was a disguise.

Tonight everybody has to have new pictures taken; the laminates need to be replaced because the old ones keep getting bootlegged. I’m not sure why anyone would go to the trouble. Just to hang out backstage, maybe? It’s not like you’re gonna be able to cruise into the U2 dressing room with that piece of plastic—you also have to have a note from a certified deity, or, uh, you have to be one.

Next day we drive ten hours to Minneapolis, through desultory gray snow flurries. Wisconsin has an inordinate number of large plastic animals resident beside its roadside gas stations and gift shops (pink elephant, brown moose, white cow), but we did manage to see an actual live deer, frozen in our headlights.

The next day, arriving at the Target Center, there’s a rumor that Julia Roberts is visiting U2 in their dressing room. What is it about celebrity that it can only relate to other celebrity? Why does Julia Roberts have an automatic connection with some rock band from Ireland? Do they all sit around and discuss how hard it is to get good help these days?

Chicago, Illinois, March 31: Someone tells me that Bono’s arm is killing him—to the point that he requires special massage assistance—as a result of being pulled on all the time by overeager audience members. The price (sigh) of fame.

For me, the highlight of the evening is the free Terminator II: Judgment Day video game backstage. Kill! Kill! Kill! Some guy from the U2 crew plays with me, and together we nearly save humanity from extinction before getting bored. Later, friends take us bar-hopping in Chi town, to the point where I get really sick, which I guess means we had a really great time.

Austin, Texas, April 7: After three tries, Bono manages to put a mike stand through one of the video monitors in Houston last night. Maybe he was moved to violence by false reports that there were more people killed last year by gunshot than by car accident in the state of Texas.

Houston, and Dallas before that, are scary cities right now. Tall glass buildings sway emptily in the Texan breeze, built in the certain knowledge of a glorious, oily future for all, and now mute reminders of hard times. The creaking, once-proud hotels we stay at sit in the midst of growing decay. We run from bar to hotel, heads down.

Austin is a different story. Sitting atop the Sheraton in the tallest bar in the city, light and life spread out for miles in every direction, I resolve never to leave. Later we walk across the street to the local head shop (“The Gas Pipe”—I didn’t know these places still existed). Improbably, but somehow inevitably, as we walk in, “Stairway to Heaven” is playing. I can’t decide between the freebase pipe or the hydroponic plant growing system, and leave without buying anything.

Los Angeles, California, April 12: Christina the “Mysterious Ways” belly dancer must be starting to feel claustrophobic. She has to sit or squat in this tiny black box for most of the previous song; the box won’t open until it’s time for her to make her appearance. After her gig. though, she gets carried backstage by some burly U2 crew guy, and then she doesn’t have to do anything else for the rest of the show, so maybe a little claustrophobia isn’t so bad.

Ringo-friggin’-Starr, man. He walks right by me, nodding coolly, as if to say, “Yeah. You know who I am.” The kids at SPIN will just never believe my luck.

U2’s guest list is so absurdly star-choked that they rent one of those cheap wraparound electric signs and mount it near the stage, endlessly displaying the guest list to the crowd. Watching the show from the soundboard in the middle of the arena, I’m once again awestruck by the banks of computers, monitors, and strange radar-scope machines (these analyze the exact shade of color of the lights to allow for precise mixing and matching) needed to control the lights and video screens. If only I could get a system like that for my apartment.

Miami, Florida, March 1: (nonlinear time-space jump—hold on, everybody!): Yesterday’s rumor of U2 having eight chartered jets (two for each band member) has been reduced to a rumor that they have two chartered jets (which turns out to be true). Walking by the band’s dressing room, I’m instructed not to talk out loud, because they’re listening to tapes. “You mean they’re recording?” I ask, thinking I must have misheard. “No, they’re listening.”

The show’s delayed today—it’s the first time the crew has had to break down the production and set it up in another venue, and they didn’t get a chance to practice as planned the day before because sound check ran longer than expected. So there’s a lot more time sitting around than usual. U2’s dressing room is right next door, which wouldn’t be remarkable except that my mom is also here tonight, and she’s got it in her head that she wants to meet the band. We spend some time in the hallway, watching the band occasionally mill around, accompanied by its personal security. Bono even stations a bodyguard outside the door when he goes to the bathroom. I’m not sure why he thinks he’s in so much danger even backstage, where non-laminate-bearers are summarily shot, but maybe he knows something I don’t.

Then again, maybe he just knows my mom is there. Hell, he should be scared. Mom takes it as a personal affront that none of the band have come by to say hello to Support Act (I try to explain that it’s only the second day of the tour, and they’re probably really busy, but Mom’s not buying it). “I’m going to go tell that Bono how rude he’s acting,” she announces. “Which one is he?”

“The really short one,” I tell her, hoping to put her off (they’re all really short, in actuality, though Bono seems shortest).

“Well, I’m going to go have a talk with him.”

“Uh, just hold on a second, Mom. It’s ‘Time Out’ in the halls.”

“Time Out” is the period of five minutes before and after U2 takes the stage when no one is allowed so much as to poke his/her head out the door, in case someone, I don’t know, should inadvertently wish the band “Good luck” or something. God help anyone caught wandering the halls during this period. So me and my dad form a cordon in front of the door to prevent my mom from peeking outside (you never know if she’s serious).

In retrospect, I probably should have let her loose. Bono would probably have gotten a kick out of being lectured by somebody’s mother. What’s happened with U2—as it has, doubtless, to many Big Rock Acts before them—is that people act a certain way in anticipation of things that might or might not bother the band members themselves, so that much of what goes on around them, they remain forever unaware of—like the court of some all-powerful king, where people are put to death for imagined offenses that the king himself never noticed. This explains anomalies like the recent Negativland U2 parody record controversy, and the story someone told me not long ago about a writer for a music TV show who allegedly was fired because of some imagined slight against U2 that neither the band nor its management had even noticed.

Nevertheless, organizations—like people—are usually paranoid only to the extent that they take themselves seriously, and U2, for all their attempts to put on a comic face on the Zoo TV tour, takes this production incredibly seriously.

As well they should, I guess. Reports of the proposed late-summer stadium tour suggest that it dwarfs the current show both in scale and in ambition. Zoo TV is a very carefully planned, long-term (the band is supposed to tour worldwide well into 1993) assault on the hearts and pocketbooks of music lovers everywhere. A certain amount of care and caution in the undertaking is understandable—but, you know, this doesn’t have to be a paramilitary operation; everything in moderation, boys. Or else I’ll have to sic my mom on you.

Postcript: “Hello?”

“Hi, Mom. It’s me. Seems like you should have said something to Bono after all. U2 is apparently really upset that I’m printing this story—their manager, especially. Though I hear Bono’s a little freaked out, too.”

“What didn’t they like?”

“They haven’t read it yet. They’re not concerned with the content of the story—they just don’t like the idea that it happened outside of their direct control. It’s just a neurotic reaction, which is apparently the only way a megagroup like U2 knows how to react. It’s automatic, unthinking. Unnecessary. It seems, to me, like another example of how a large, and largely paranoid, organization tries to control what’s said about its constituents. But I don’t think that’s right, you know? I mean, they’re just a pop group.”

“Well, try not to get too upset about it, dear.”

“I’m not upset, really. I’m not. Just disillusioned.”