By 1991, Soundgarden had reached a crossroads.

All around them, things seemed to be in a state of flux. The Cold War had finally reached its decades-long denouement with the dismantling of the Berlin Wall, just as a new, hot one was about to kick off in the Persian Gulf. Hip hop was emerging as a dominant new genre, while hair metal was enjoying the last few flickers of its cultural relevance. And, after several years operating within the indie underground scene around Seattle, releasing cult-favorite records for Sub Pop and SST, Soundgarden were now major label operators, with major label pressures and major label headaches.

“That’s probably one of the most tumultuous times in the band’s career,” the group’s guitarist, Kim Thayil, admitted. “There were struggles there, but creatively it propelled us into more inventive and more risk-taking, creative activities, that ultimately was really beneficial.”

Of all the struggles the band endured during this period, it was their attempt to get back on track after the departure of founding bassist Hiro Yamamoto that gave them the most agitation and distress. Yamamoto departed shortly after the release of the band’s second full-length record Louder Than Love two years earlier. Soundgarden searched high and low for his replacement, and the fruits of that search would ultimately have a massive impact on both the sound and aesthetic of their follow-up to that project, a lacerating punk-metal hybrid that they named Badmotorfinger.

Badmotorfinger is the moment that Soundgarden essentially became the Soundgarden that most of the band’s millions of fans across the globe recognize today. It’s the moment when four fingers locked together, forming a fist made up of savagely complex, riff-riddled rock that punched through the zeitgeist and dominated MTV airwaves and FM stereos for years to come. It’s “Jesus Christ Pose” and “Slaves & Bulldozers.” It’s “Looking California” while “Feeling Minnesota.” It’s the “Rusty Cage” they created and desperately needed to break.

For the band’s singer specifically, Badmotorfinger represents the crowning achievement in one of the most impressive stretches of inspired songwriting that any American artist has achieved over the last several decades. Fueled by a sense of loss, Chris Cornell tapped into a special vein of inspiration throughout 1990 and into 1991 that would serve as the foundation not just for this seminal record, but also Cameron Crowe’s Seattle-centric film Singles, as well as Temple of the Dog; the one-off dedication to his friend and roommate, the late Andrew Wood.

“We were just trying to be as honest with ourselves as a band and as musicians as we possibly could,” drummer Matt Cameron said. “That meant we were trying to write music that was pretty meaningful to us.”

Here, 30 years after Badmotorfinger made its ferocious introduction to the world, is the full story of its creation, as told by the band members themselves as well as a variety of folks pivotal to the larger story of that time and place, when anything seemed possible.

I: Before Soundgarden could get to work on their third studio album, they first had to find a new bass player. Ultimately, the search came down to two guitar players, both of whom had ties to a band from down South in Puget Sound named Nirvana.

Matt Cameron (Soundgarden drummer): Hiro [Yamamoto] quit Soundgarden pretty much right after we made Louder Than Love. That was ’88 or ’89. Something like that. He was sort of feeling like he didn’t want to tour and commit as much time and energy to the band as it was going to take at that time. We had just signed a deal with A&M Records. That was our first major record release. Kim, Chris and myself were really excited to start our journey as a rock band. So, when Hiro decided to leave it was definitely a momentum killer for us, because we had all of these touring plans pretty much ready to go.

Chris Cornell (2011): Hiro’s absence was something we were living with long before he actually left the band. He was an extremely creative person in the beginning, but that waned quickly.

Kim Thayil (Soundgarden lead guitarist): There’s significant loss when you remove a songwriter, a founder, and someone with a unique and distinct musical personality like Hiro has. Replacing Hiro was a really important thing. And a difficult thing. We auditioned a number of people. Some of the standouts were Ben Shepherd and Jason Everman.

Ben Shepherd (Soundgarden bassist): I went to a Pere Ubu concert. Kim told me that Hiro left the band. I got all irate. The way I saw it, it was Hiro’s band and he quit, so I thought they were breaking up. And Kim’s like, “No, no, no. Calm down. We’re not breaking up.” God, I miss how they used to play together. But Kim said, “We were thinking about, what would you think about trying out on bass?” I was like, “That’s funny, because last night the guys from Nirvana asked me to try out on guitar.”

Cameron: We were really good friends with [Ben’s] big brother, Henry. Kim had known Henry before he met Ben. I met Ben right when he came over to audition. I’d never seen him play in some of the local bands he had at that time, but I know that one of the bands called March of Crimes played some shows with Green River. He was definitely part of our local music scene for sure.

Shepherd: I was in a band before March of Crimes that that had played a show there at Hiro’s house. I think that’s the famous house that he lived in with Chris and everybody.

Thayil: [Nirvana guitarist] Jason Everman was really focused and prepared and professional. I remember we each made a list of who our preferences were, sort of like rank voting and Jason came out ahead for reasons of professionalism and preparation and we felt he would learn quickly.

Shepherd: I’d never really played bass before. I remember sitting out in the freezing cold in my friend’s garage, where Nirvana used to practice, when Chad [Channing] first joined the band, over on Bainbridge Island. It was freezing cold. Tried to learn “Loud Love.” I borrowed a bass from a buddy of mine, and I would sit there out in the freezing cold garage trying to learn these things off a ghetto blaster.

Cameron: We just wanted to find someone that we knew locally and that we were friends with and that we had seen play in various bands. We rehearsed with Ben once or twice. We didn’t choose him because he hadn’t really learned the music and we had to get straight out on tour. The transition into Jason was definitely a practical one. We found Jason through local friends. He had been with Nirvana, briefly, and we were really good friends with those guys. He definitely came highly recommended. We did a straight year of touring with Jason; it was late ’88, ’89.

Shepherd: Soundgarden came back, and Stuart Hallerman told me they’d chosen Jason Everman to play bass. I had gone through middle school and high school with Jason, so I already knew him. I told my girlfriend at the time, “Watch. In six months, they’ll come back and get me,” being all cocky, or whatever. I was all deflated.

Thayil: We were certain that [Jason] would be a great fit. And during the course of the touring with him, during that cycle, it was not supplanting the creative and social dynamic that we had lost when Hiro quit. And it was creating other problems. There was a band bonding that was sort of disassembling in a way, and the addition of Jason wasn’t really helping it.

Cornell (2011): We did 100 shows with Jason Everman in between Hiro and Ben, and we didn’t have one song or even an idea of a song with him.

[embedded content][embedded content]

Thayil: We felt that for the success and for the health of the band, we probably would have to make a change, and find an element that would supplant those relationships in a way that was dynamically creative. The next guy on that list was Ben, who we realized had a good creative sense about him and was very inventive when he played.

Shepherd: Almost six months to the day later they came back…and asked me to join. Under the guise of meeting Chris’ new puppy Howdy, we all went to West Seattle. We sat around a picnic table out on the lawn and Chris goes, “We were wondering if you’d want to play bass for us?” I spit on the ground and said, “Okay, but let me tell my friends at home.”

Terry Date (Louder Than Love/Badmotorfinger Producer): I wasn’t really involved with why Hiro left after Louder Than Love. That was sort of internal band stuff. But Ben fit in perfectly with those guys. It was just a really natural transition. To my eyes anyway, it was no different between the two. I think as far as band dynamics, it may have been a little different, but I wasn’t too deep into the internal workings of the band.

Cornell (2011): It was when Ben joined the band that I realized, “OK, we’re going to have a future with this. We’re going to make great records.”

Shepherd: I was so honored and freaked out and over my head, but still within a brethren of those three guys, those three mentors taking me under their wing, I was a little brother. I was way younger than them. It made me feel like Charlie getting the Golden Ticket at the Chocolate Factory.

II: With their new bassist on board, it was time for Soundgarden to get down to the business of writing songs and working on their next full-length record. Having emptied the vault of new material on previous releases like Ultramega OK and Louder Than Love, however, meant they’d have to start that process from scratch. That wouldn’t be a problem for Chris Cornell, who was just then entering the most prolific songwriting stretch of his entire career. The addition of Shepherd, and his inventive, off-kilter tunings was a tremendous boon as well.

Thayil: Up until Badmotorfinger, almost all our songs were introduced and live tested, because we’d write them in rehearsal, whether it was the attic or the basement, depending on which house Chris and Hiro were residing at. We would debut them at our shows and get a really good idea of what our friends and family liked, and a really good idea of what the other bands liked. With Badmotorfinger, that’s the first album where we didn’t have the fortune of audience appraisal of the material. We had to totally go on our own instincts. And at that point, we were already our own best or worst audience, but at that point, that’s all we had.

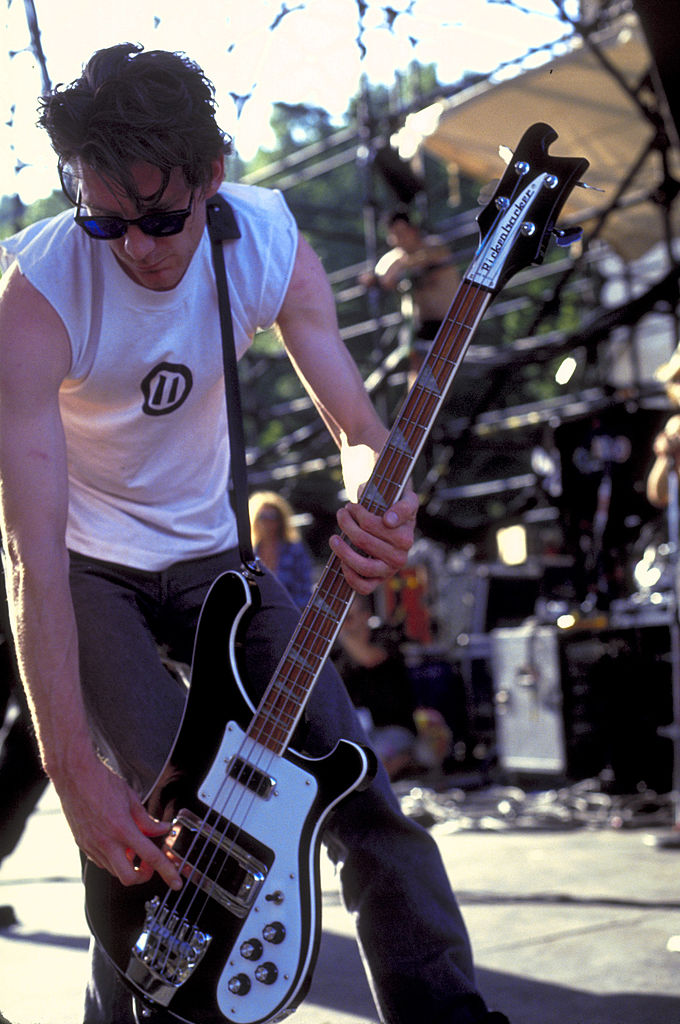

Cameron: Ben came in as a guitar player. He wasn’t really playing bass in bands at that period. When he first came and jammed with us, I noticed that he had a lot of guitar techniques with his bass playing, so I tried to zero in and let him know things that I zero in on as a drummer when I play with a bass player. After we had those initial couple rehearsals, he clued into exactly what I was trying to do as a drummer. One thing that we were really impressed with was how creative he was as a player, songwriter, musician. He fit the creative dynamic we were at during that point of our career, like 1990. Kind of right before we started writing and recording Badmotorfinger.

Date: I don’t think Ben’s ever been awed or daunted by anything. Ben pretty much handles any situation in his own way really well. He was great the whole time. I mean, he was being Ben the whole time. He had this great kind of punk rock mentality that was really unique. Probably that was different from Hiro.

Shepherd: During that rehearsal, I got Matt to jump up from the drums and shake my hand because of the clam I made. I missed a string because I’m not a bass player first, right? I missed the string and then I landed back, and I got it corrected and just stopped. Matt was just impressed by that and jumped up, laughed. He was like, “Right on, man! You nailed it.” “No, I didn’t nail it.”

Cameron: Once Ben joined the band, I think our creative powers just changed a little bit. We had this other element in there. I always joked that Ben and I were trying to make a jazz record and Kim and Chris were trying to make the ultimate hard rock record.

Stuart Hallerman (Engineer/Friend): It was mid-January up until album time they spent rehearsing. Avast [Hallerman’s recording studio in Seattle] was pretty slow up until then. I’d only been open for like, seven months. At first, they wanted three or four days a week. They would only wanna rehearse for half a day. Show up at beer thirty and do an afternoon thing, depending on their life schedule. It sort of became their clubhouse to a degree. January 15 was night one. I remember because we had a little black and white TV. Bombs are dropping and it’s the beginning of the Gulf War. Ah fuck. So, they set up and started jamming; making Soundgarden-type noises. They got their trademark way to let the monsters out and stuff. It pretty much coalesced into “Slave and Bulldozers” from that first day.

Cornell (2011): The challenge for me was, “How can I write a visceral, up-tempo, aggressive, post-punk rock song with screechy vocals, but that’s not a heavy metal song or a retro hard rock song?” It sounds like what we were, which is a band that’s all over the map.

[embedded content][embedded content]

Shepherd: Chris was absolutely open-minded and accepting of every idea. And then he would take something and finish it, and every time it was like, “That is cool. That is Soundgarden all the way.” You know what I mean? When you daydream about working on something with someone, he would be the ultimate partner to work on something with. He could basically finish your sentence for you. And his lyrics were incredible.

Cameron: Chris was writing a ton of amazing music. I was just starting to come into my own as a songwriter in Soundgarden. Ben was really fun for me to work with as a songwriter just because he was so encouraging and really positive. I felt like one aspect for me that made Badmotorfinger a jumping-off point was that this was all new material. There were no leftovers on that album. We had all been able to quit our day jobs around the late ‘80s, like ’88, ’89, right around the Louder Than Love period. We were able to focus on songwriting, rehearsing, playing gigs, just everything that comes with being in a semi-successful rock band in the late ‘80s.

Cornell (1992): What happens for me is the creative process continues, you write songs that you enjoy, you go into different fields musically because you’re bored with the last thing you did or you’re bored with what everyone else is doing, and something might jump out of the sky. That’s sort of how we’ve always approached it. There’s never been a time when we had a really popular-sounding song that we felt was really good, but we just didn’t do it because it was pop… I could write a song that is pure pop, but would it feel right for Soundgarden? The whole idea was that we don’t change for the marketplace as it exists, we just continue to exist until the marketplace changes for us.

Cameron: One thing I really noticed with Chris, in particular, is, when he and [Mother Love Bone singer] Andy [Wood] were living together at Chris’s house on Capitol Hill, he was recording a lot on his four-track cassette recorder. He wasn’t recording just hard rock Soundgarden-type songs, he was really trying to stretch out as a songwriter. I don’t know if it was a conscious thing or not. He had all this music inside him that he just wanted to try to get out in whatever way felt most natural. I remember hearing a bunch of gorgeous acoustic-type music that he was writing around that time. It had nothing to do with Soundgarden or even Temple of the Dog. I think Chris was really channeling his inner creative life — his inner emotional life — in a way that just seemed effortless. From an outsider, someone like myself, it’s kind of hard for me to write music. One thing I’ve noticed about Chris during that period is how many great songs he wrote, demoed up, and played for us. Some of the stuff he would just play for me or some of his friends or whatnot. The pace at which the amazing amount of music was coming out of him during that period was very impressive.

Hallerman: Around Thanksgiving, Chris wrote the Poncier tape [a five-song, solo compilation demo for the film Singles]. A month before that he did Temple of the Dog, a whole different album with beautiful singing and expression and stuff. He did that during the writing of Badmotorfinger.

Thayil: The Poncier thing was probably a consequence of the work he was doing with Temple of the Dog and Badmotorfinger. Basically, he’s coming up with a number of musical ideas and lyrical ideas, melodies, and guitar parts. He knows what will work with the guys from Mother Love Bone, and he’s showing them songs. He knows what will work with me and Matt and Ben. The idea that he took these song titles and then concocted, overnight, five interesting musical pieces, is probably not likely the case. It’s probably musical ideas that were being generated all along during this period of time. He was always playing guitar and recording ideas.

Cameron Crowe (Director, Singles): [My ex-wife] Nancy [Wilson] went out to a club, while I stayed home in Woodinville. She ran into Chris who gave her the [Poncier] tape. He said, “Here’s what you wanna do. Go home and tell Cameron you ran into some guy on the street who was busking and had a cassette to sell, and that you bought it and brought it home.” So, she did that. And I looked at the cassette and it had all the fake titles from [Pearl Jam bassist] Jeff Ament’s little art piece copy that he had done for the movie Singles. It was like, “What? What is this??” So, I put it on, and it was Chris. I couldn’t believe how fully realized it was, and how different it was. How elegant. I loved all the songs, but “Seasons,” stood out from the first listen with that Zeppelin, open-tuning vibe. It was like, “Holy crap!” It was the best thing I’d heard in a really long time. It was a facet of Chris that I wanted to use; this rich vein of Chris’s solo impulses. Stuff that’s not particularly Soundgarden, but very personal and him. It quickly went from mind-blown, to how can we make this part of the sound of the movie?

Thayil: Chris learned from Andy at some point, rather than editing what he was doing to address the aesthetics of his band, he decided he would just write it, record it and just put it out there as an exercise per Andy’s advice. And that’s when he became really prolific. Then he writes all this stuff for Temple of the Dog, which, granted, are great songs, but probably a little bit easier to write because the audience is maybe more…general as opposed to the specific band idea and attitude. It’s something that can cross over with a number of different types of bands, and he did great with that. And then at the same time, he’s throwing out these ideas that are a little more experimental and more arty. Well, that he can go and show Kim and Ben and Matt.

Cameron: I remember for Badmotorfinger, Chris and I got together just the two of us at Avast! Studios. I think it was early ’90 or late ’89. He probably had six or seven ideas. One of them was “Rusty Cage,” and the other one of them I believe was “Outshined.”

Cornell (2011): I wrote the lyrics [to “Rusty Cage”] in my head when we were in a van somewhere in Europe on tour. I honestly can’t remember where, exactly. But I have a vivid memory of staring out the window, looking at the countryside, and feeling pent-up. I never wrote any of the words down, but I somehow remembered them. When we finished the tour and Soundgarden returned home to Seattle, I picked up a guitar and tried to come up with music that I felt matched the essence of that song. I wanted to create this hillbilly/Black Sabbath crossover that I’d never heard before. I thought that would be cool and possible. I thought, “If anyone can do it, Soundgarden can do it.” I was listening to a lot of Tom Waits at the time, and I wondered how Soundgarden could approach similar imagery and I wondered what the music would sound like. “Rusty Cage” is what I came up with.

Hallerman: Chris wrote and demoed on eight-track. He had his brother Peter’s eight-track set up on a home studio in West Seattle and he’d program a drum machine and then do bass parts and a guitar part too and sing multiple parts. But it would take him a couple of days to program the drum machine per song and he had a bunch of songs in his head, so he just grabbed Matt and me and was like, “Can we just come into Avast for two days and work it out.” So, he programmed Matt to play the songs, which is as easy as describing the song once, and then Matt plays the song. Together with those two, it was like, “Hey Chris, what should I call this collection of songs?” And he’s like, “Uh…More Brilliance!” So that was “Holy Water,” “Drawing Flies,” “Rusty Cage,” “Outshined,” “Face Pollution.” “Searching With My Good Eye Closed” was on that, but he did it at home. “Mind Riot,” and I think “New Damage” was too. All sorts of great things.

Cameron: I was able to tailor the drum part at a very early stage. If anything, that’s one of my greatest contributions to music — helping Chris unlock his potential. I think at that time, he was thinking beyond what he was able to do. Sometimes, really great songwriters, they can’t always get on tape what they’re hearing in their head. I think when I came in there, I was able to play stuff that he was hearing in his head. I’m really glad that I had some small part in his musical development at that point.

Thayil: I think through some conversation Chris had with Jeff Ament; Chris and Jeff were talking about different tunings and Jeff said, “Imagine if someone tuned every string to E. Wouldn’t that be stupid?” And Chris thought, “Yeah, that would be weird if someone just tuned every string to E.” And then he wrote “Mind Riot.” He basically just took it as a challenge like, “What would that sound like? What would that be?” He did it and then brought in “Mind Riot.” I’d go, “Why the hell did he do this?” You could probably write the song in a more friendly tuning. It was such a curiosity that he went ahead and did it anyway.

Hallerman: Chris did a demo of “Searching With My Good Eye Closed” and this song “Dirty Candy.” I don’t know where that one went. Killer song.

Cameron: A song like “Searching With My Good Eye Closed,” Chris had a drum machine that he had programmed pretty much for the whole song, and I thought the parts were really, really cool. I learned them and I stuck pretty close to the programmed parts from his demo. That was an example of a drum pattern that you came up with at 100% that I fucking loved. He didn’t say, “Oh, hey, learn my programmed drum part,” or, “Learn my demo drum part.” He never said that to me. He pretty much let me decide what the final drum part was going to be. I think he trusted me. He knew that what I brought to the band was my own thing. I think from when I first met him in like ’84, he noticed something in me that he liked.

III: Cornell wasn’t the only member of the band who was realizing his fullest potential as a songwriter. Finally free from the distractions of their respective day jobs, Matt Cameron and Kim Thayil were also contributing wildly vivid lyrics, creative rhythms, and brutal riffs.

Date: Matt is one of the best drummers I’ve ever worked with. He’s a machine. He was automatic and made it really super easy. Matt was just one of those guys; he understood the timing, the time signatures. They all did. They all were well ahead of most people as far as that stuff goes.

Shepherd: He makes everything so easy. Everything we do is on time. The one trick with playing with Cameron? Don’t look at him. It’ll screw you up because you’ll get so mesmerized watching him, that you’ll miss notes, you’ll miss beats, you’ll miss playing. You can’t look at him. If you ever jam with him, watch out. Don’t watch him.

Cameron: I remember I wrote a lot of my Badmotorfinger songs in May 1990. I have this cassette tape that says 5/90 on it, and I wrote “Room A Thousand Years Wide,” “Drawing Flies,” and “Birth Ritual.” It was a really weird creative period. The bridge for “New Damage.” It was a really interesting burst of creativity for me. At that point I didn’t have my day job anymore, so I was spending a lot of time in my bedroom with my four-track cassette machine, playing guitar, trying to come up with riffs that I thought the guys would like. I had always been writing my own music for my own pleasure up to that point. I think I started really getting influenced by Kim’s guitar style.

Hallerman: Kim wrote riffs and brought them in. He had a four-track too. But mostly he had three-fifths of a song in his head, and he’d bring it to people and they’d craft the lyrics together. Once he took one of Matt’s songs and wrote lyrics to it because he wanted to do that exercise. “Room a Thousand Years Wide.” That song was originally done as a Sub Pop seven-inch backed with “HIV Baby.” So, it’s two different performances. One was with Terry Date down at Studio D, and the seven-inch was done with me at Avast.

Thayil: I love Matt’s riff on “Room A Thousand Years Wide,” which is in drop D. It didn’t have lyrics at the time. Matt gave us a demo and we learned how to play the song. I forget what timing it was in, six or five; one of those two. I just loved the groove and so I wanted to go ahead and try to write lyrics for this. Ultimately, they were about identity as part of referencing some philosophy thing; extrapolating from the idea of identity and creating something that’s a little bit more mysterious. I remember [Seattle music producer] Steve Fisk left a message on my answering machine where he referenced some movie. There were a bunch of witches sitting around. Haxan is the one that I was just thinking of.* But the line was “Tomorrow begat, tomorrow begat, tomorrow.” It’s like “Oh excellent. That would be a great way to end the song.” Since what I was discussing in the lyrics about identity, was plotting it temporally. And since I was talking about transcendence, identity and time, I thought “This is great. I’m going to rip off Steve’s answering message, “Tomorrow begat, tomorrow begat, tomorrow.”

*In a follow-up, Thayil clarified that the reference for the lyric “Tomorrow begat tomorrow” from “Room a Thousand Years Wide” was from the 1857 book The Hasheesh Eater by Fitz Hugh Ludlow, as told to him by Steve Fisk. In the book, Ludlow consumes cannabis extract and describes in vivid detail the myriad changes in his consciousness and philosophical outlook.

[embedded content][embedded content]

Shepherd: I don’t think Kim gets enough credit for that stuff. It’s like, “Holy fuck.” Kim does not get enough credit on guitar or writing that he deserves. It’s like watching an ocean roar against the shore, but somehow has lightning bolts in it. I don’t know how to describe it. It’s like shooting stars with fucking orange sherbet.

Date: You know, in a typical band over the years, there is usually some sort of rub between the guitar player and the singer. You can go through history and see that. I never saw that with these two guys. Chris and Kim always had great respect for each other. They communicated well with each other. I wasn’t around for the writing process, so if there was any tension, it probably would have been there. But for the recording process, everybody allowed everybody to do their thing and with great respect for what each person was doing. There was no one guy coming in saying, “You can’t do that that way.” It was none of that. Everybody seemed to allow everybody to do their own parts.

Scott Granlund (Saxophonist): At some point, Matt called me up and said, “Hey, we’re doing the Sub Pop single of the month. Kim and I have this song, well, two songs actually, and I can hear some horns in it. So, we got together, worked on some stuff and recorded “Room a Thousand Years Wide” for the single of the month. Then a little while later, he called again and said, “Hey, Soundgarden got a major label deal and we’re gonna record it again for a CD release.” So, then I recorded the Badmotorfinger version.

Thayil: Scott Granlund, if you didn’t know, also plays guitar. So, in a number of these groups or projects he’d play guitar or sax. He’s primarily a sax player, but he also had guitar sensibilities and voila, it sounds like the Stooges. Because as a sax player, he had an understanding of what the band was about and what a guitarist might want to hear a sax player doing.

Granlund: I did “Drawing Flies” too. Did that with a baritone. Well, double-tracked with one track a tenor, and one-track a baritone.

IV: The only song on Badmotorfinger where all four band members received a writing credit was the lacerating lead single “Jesus Christ Pose.” The song was at least partially inspired by a photo Chris saw of Jane’s Addiction frontman Perry Farrell staring into the camera with his arms outstretched on a bed, shot by his friend Chris Cuffaro. Ultimately, “Jesus Christ Pose” is a lacerating mediation on media and religion set over some of the most chaotic, breakneck rhythms ever concocted.

Perry Farrell (Jane’s Addiction): I’m Jewish, so I don’t do Jesus Christ poses. Although Jesus was a Jew, so maybe I do, do Jesus Christ poses! Here’s how it went down. [Photographer] Chris Cuffaro was above me on a ladder. It was like the last shot. And he said, “Do something!” So, I reached up to him. If he wouldn’t have been standing over my head on a ladder, he wouldn’t have been in that position. It’s not a Jesus Christ pose, but it’s not about me either.

Shepherd: We all showed up at Avast, and Stuart had made this weird little stage storage unit in one half of the studio. It was like a showroom. So, Matt’s up there, we’re all putting on our guitars. And Matt starts doing that riff [for “Jesus Christ Pose], and I started playing to it.

Cameron: I think that was during the mid-Badmotorfinger songwriting period at Avast! Here in Seattle. We were sort of between tours and whatnot, working on music that would eventually become the Badmotorfinger album. We were working on a lot of Chris’s demos at that point, getting arrangements down and whatnot.

Thayil: The people in the room were Matt, Ben and myself. I remember standing on that stage and Ben was on the floor next to it. The drums might have been up on the stage too. I just remember looking at them, and Ben just started this riff; started playing really fast. Because the floor was cement, the bass rumbled and it was hard to get a distinct idea of the one with the rhythm, because it was just blurry because of the cement and the echoing. But Ben was standing near Matt, so Matt could hear what was going on. So, Ben’s doing this riff, it’s very fast, it was just a smear to me. Matt starts off with that drum riff; one of the most insanely fast difficult drum rips for a rock style ever. That gave me the idea of where the song was. It still is hard to tell where the one was because Matt’s drum riff was kind of rolling but somewhere in that circle is the one. Eventually, I picked up on it and came up with that screaming space bat, I don’t know what we called it then, I don’t if we described it as lighting or some weird kamikaze bat, but that “Beedly-whoop-bang” that part started coming out; that main riff and then that squealy guitar part. Then Chris turned up and tried to learn what we were playing.

Cameron: My recollection was I sat down and started playing that groove, and everyone dove right in. I remember thinking, “That was a really good jam we did, I hope Stuart recorded it.”

Cornell (1992): What ends up becoming a Soundgarden song and record is definitely a collaboration between all four members, not just what the individual member put in, but also what the four members take out. So, songs come in and songs go out.

[embedded content][embedded content]

V: While the band was assembling and building songs at a fervent pace, it became inevitable that some were going to be left out of the final tracklist. Some were harder to cut than others.

Date: One of my favorite songs on Badmotorfinger didn’t make it on the record because it made it onto the Singles soundtrack and that was “Birth Ritual.” Those vocals were actually recorded by, I believe, the owner at Bear Creek.

Crowe: I just loved Soundgarden. I had seen one of their earlier shows and Chris was around. I loved their dark, slow-moving, intense melody. I remember telling all my friends that this is a band that has it all. When I met Chris, I felt a lot of simpatico with him. I felt like of all the people up there [in Seattle] that we would have been friends in school apart from all of it. Sometimes you feel a familiarity, and that never changed. Then I tried to figure out a way that he could be in Singles, and I could utilize his power and show a few more people what I’d seen. It felt like one of the best reasons to make the movie.

Thayil: There are two different basic tracks for “Birth Ritual.” The other one I think might have been recorded with Stuart. It seems to me that we would’ve done basic tracks for “Birth Ritual” for Badmotorfinger at some point. That song also had some weird arrangement issues. I don’t know if “Birth Ritual” was something that was relegated to B-side status, or it was an idea Matt had, that actually was completed and developed in some timeframe that we’d fit with the Singles soundtrack. At some point, Chris came up with lyrics and he added some musical parts that would’ve fit with Matt’s ideas to complete the song.

Crowe: Chris was an amazing person to collaborate with, and he understood what we were going for in the movie. We wanted to have a powerful representative slice of Soundgarden, and the idea was to have it be something new. So, he gave me a cassette with “Jesus Christ Pose” and “Birth Ritual” on it, and we discussed the pros and cons of each one. There was a scene in the movie where Campbell Scott’s on the floor of his apartment and he’s kinda spread out in a pose. I knew it wasn’t close to that scene in the movie, but I just didn’t want to summon any self-revelatory imagery that didn’t really belong. Plus, I thought “Birth Ritual” was gonna explode. Chris was good with the choice and agreed. He smiled and said, “Now do we want to do this with a shirt on?” I’m like, “Naw, let’s take the full Chris Cornell shirtless road for this.”

[embedded content][embedded content]

Cameron: Some of my favorite Chris songs are B-sides. “She Likes Surprises,” “She’s a Politician,” “Cold Bitch.” Some of his best songs are B-sides and those are amazing songs. “Fresh Deadly Roses” is another incredible B-side that never made the cut. Those are good problems to have. If you have too many good songs, I guess you’re going to have to throw a couple to the B-side pile.

Shepherd: For some reason, Kim and Chris didn’t want “Cold Bitch.” But when we tracked that, man. That was a fucking heavy day. We were there at Bear Creek [Studios], me, Kim, Chris. I don’t think Matt had gotten there yet. The power went out as the cellos were playing. A lightning strike hit the lawn outside and put the power out as they were tracking. It was so fucking heavy. It was like, “That is the mojo song of the whole record, man.” That would’ve… I think that would’ve catapulted that record to another level immediately.

Cameron: “Cold Bitch” is one of my favorite Soundgarden songs of all time. I was just crushed that it didn’t make the cut. It was Chris’s call. I remember we were at a Denny’s and when we were mixing the album in Tarzana or something. We were like, “Okay, what’s our sequence for the album?” We all figured out a sequence, and then Chris vetoed “Cold Bitch.” He wrote the song, so he had veto power on that one. I was just like, “Aw.” He said it didn’t groove. I’m just like, that’s the grooviest! It’s a weird groove, super weird. He didn’t like the vocals…He just didn’t hear it. To this day, I’m just like, “Ugh, that should’ve made the cut.”

VI: With the stockpile of songs growing, time was drawing near to properly kick off the recording process To help assist them behind the boards, Soundgarden turned once again to Terry Date, a local producer who assisted them during the creation of their previous record Louder Than Love.

Cameron: We were working with Terry on the Louder Than Love album. We knew him from his work with Metal Church. He’s just a great guy. He was someone that had experience in Seattle at that time and made major label albums. When we signed our deal, we had to use a producer. We didn’t want to use anyone that was going to change the music or anything, but he was someone that was able to give us that fuller sound in the studio.

Thayil: I didn’t think of him as a metal producer. He got that title after working with us. But he came from a kind of a pop, new wave band called The Cowboys, that were big in Seattle. If I remember correctly, the two records that stood out in my mind was when he did a Metal Church album, which yes, that’s metal, but it’s somewhat indie. And then he did a Sir Mix-a-Lot. As a matter of fact, I think Terry’s first gold record was Sir Mix-a-Lot [for Swass].

Date: I was managed by Soundgarden’s management company, as well as what became Pearl Jam’s management company. I was introduced to them by [Soundgarden manager, and Chris Cornell’s then-wife] Susan Silver and they had just gotten their deal with A&M. We became good friends after that. I actually lived fairly close, like a block away from Kim during time actually.

Thayil: Terry’s not a musician. He’s an engineer. He went from being a sound man to a recording engineer. He knows how to hear these instruments and he understands percussion from working with Mix-a-Lot and rap and drums and then he learns how the guitarist wants to hear their guitars by working with a metal band. He came to work with us and had an idea of how things sound.

Date: I had done a record [Apple] with Mother Love Bone down in Sausalito [California]. I can’t remember if it was my idea of the band’s idea, but we wanted to record Badmotorfinger in Sausalito, in that same area. I wanted to go to the same studio that we did Mother Love Bone, which was called The Plant. We couldn’t get in there because it was booked during that time period. So, the label rep from A&M, Brian Huttenhower, we met in the Sausalito area and toured a couple of studios. I videotaped them all so I could bring them back and show the band and see which one they were comfortable with. Ended up going with a place called Studio D.

Thayil: There was a room down there that Matt liked, and that Terry Date liked. So, we went down there to do basics [tracking]. The idea was maybe we would get guitars and bass as well as drums. But it’s primarily drums. We got some bass, and no guitars or vocals, I don’t think. None that I can remember. We just concentrated on getting good drum sounds and then we might have kept some of the base and that came back up here by Bear Creek to do the other stuff.

Shepherd: Sausalito reminded me a lot of Bainbridge at that time, except that Bainbridge actually had kids. Sausalito was so yuppie and clean-cut and weird when we were there. It seemed like kids were illegal. Like, “No, we don’t want kids around this part of…” You know what I mean? You don’t want to see kids in public, so there weren’t kids there. I guess, because of the demographics and the money, or whatever. Back then we were playing a lot of catch. Nerf football catch. We were fucking around all the time. We all threw our arms out during that recording in Sausalito.

VII: After finishing the drum tracks down in Sausalito, California, Soundgarden headed back home to Washington’s Bear Creek Studios to track guitars and vocals and give Badmotorfinger its finishing touches.

Cameron: We probably could have done everything at Bear Creek in all honesty. The idea was that Terry bounced the drums down to a stereo mix and then we laid out all the guitars and all the vocals up there and the bass. I wasn’t there for every session because I didn’t really need to be there, but I remember we recorded “Mind Riot” up there at Bear Creek. I think that was one of the songs that we recorded the drums for up there. Then I did some background vocals with Chris up at Bear Creek, some percussion, things like that. But it was mostly for guitars and vocals. The interaction was great. We all felt like we were progressing, like we had something that was really interesting and really good.

Date: The studio [at Bear Creek] is very rustic. An old barn. And there was an outbuilding out kind of in the woods that had a hot tub or whatever. But, it was just a small, one-room building. Chris would go out there and he’d write and work out. That was sort of his private getaway spot to think about his lyrics and that sort of thing. It’s a 10-acre lot, a 10-acre piece of property, pretty rural, pretty rustic. We had all kinds of outdoor fun. A lot of bonfires, a lot of fun and games.

Shepherd: I remember that time period too, because that was when Chris was riding his mountain bike from West Seattle to Woodinville every day. Then tracking, and then riding back.

Date: Chris was really getting fit during that record. I think riding back late at night was harder than riding out during noon, but I don’t know if maybe he got a ride back in? It’s a 30-mile round trip, probably. Maybe a little bit more. I think it’s about 15 miles each way.

Cornell (2014): I think after Andy passed away, Jeff and I spent a lot of time riding mountain bikes through the hills of Seattle and talking. That’s one of my best memories from that period, really.

Thayil: We’d go out in the backyard and play whiffle ball, and there was a fence that went to their residential property, and so the idea was that if you hit it over that fence, you hit a home run. So that was a fun thing to do. And then we invented a game with a Nerf football and a Frisbee and it was like bombardment but you throw the Frisbee, and if the guy caught the Frisbee, then he’d get a point. If he dropped the Frisbee or he was hit by the Frisbee, the thrower got a point. The most accurate and strongest arms are probably me and Ben. I could throw a baseball and Ben could probably throw it another 30 or 40 feet. Both of those would probably be much further than Matt or Chris could throw, so…

Date: It was a very good time because Pearl Jam was, I think, finishing their first record when we were working on Badmotorfinger. I remember Eddie [Vedder] coming out to visit. He had the first mixes from their first record [Ten] and he played them for us. That was really, really a fun time to hear that for the first time.

Shepherd: Everything was tracked with solar power. That was the whole point of that whole record, I do believe. Showing the progressive ecological side of recording that can be done, blah blah blah.

Date: The basic tracks were totally fun and easy for everybody. When it came time to doing vocals; the vocals on that record are very high and very loud. It’s really difficult to do, and I know Chris struggled. We’d have many days where, or not many days, but some days where we’d come in and he’d start singing, and would just say, “Nope, not today. I can’t get it. It won’t happen today.” And then there were times when…I always had a little stool, like a wood stool sitting next to him so he could put water or whatever on it while he was standing up singing. During some of those very hard, high vocal parts, he’d get frustrated, and that chair got broken a couple of times.

Cornell (2014): My history of singing has always probably been closer to a David Bowie approach than, for example, an AC/DC approach. I never thought of myself as being the singer that wanted to create an identity and then stick to that… From song to song, I would approach it in the way I felt was the most natural for it. Who was this person singing this song? What are they singing about? What should that person sound like? That’s how I would approach it, and oftentimes, that would be the most difficult part of the whole process for me: finding the right voice that felt the most natural for that song.

Cameron: One of the great things about Chris is he was up for anything, man. We threw some of the weirdest fucking shit at him. The most unsingable stuff. Like, “There’s no way, but I’m just going to send it to him anyway.” And then it’s just like, “Oh my God, he did it!” Every time Chris would put lyrics and vocals over some weird piece of music that I wrote or someone else wrote, it’s like, “How the fuck did he pull that off?” That’s one of the reasons why he was one of the all-time greats. He was able to make sense out of this really difficult angular music. There’s so many examples of that in our catalog. “Drawing Flies” was an example of him just hitting a home run on something that I didn’t really know if it was even going to make the cut. I’m so happy it did.

Thayil: I remember Ben spitting at the control room window while he was doing bass. I remember Terry saying, “Try that again.” We’re in the control room and Ben for some reason gets all pissed off and like, throws something and then runs over to the window and spits at the window. I thought, “Is he joking around or is he pissed off? Oh, well so he’s pissed off!” Terry turned and looked at me and looked at Chris, “Well what’s going on?” We go “That’s okay, I don’t think he wants to do what you’re telling him to do.”

Shepherd: If I messed up, I would get so angry, and so frustrated with myself. Not at anyone else, but I’m sure if you looked at the scene it would look like I was mad at everyone else. But I was really infuriated with myself. Too much youthful energy, instead of re-buckling and refocusing. I look back and go, “God, how did those guys put up with me?” When that happened in Badmotorfinger I would get so mad tracking. I was in a totally different headspace. I would just get irate, lose my cool, basically.

Cameron: I remember taking some rough mixes home on a cassette up at Bear Creek that Terry made for us, playing them in my Volkswagen driving home. Just loving it. Just thinking, “Oh my god, this is a step up from what we have just done.” Like we were talking about earlier, the addition of Ben Shepherd was just…it became apparent how much of a force he was in the music when we started recording.

VIII: One of the more interesting tracks to emerge from Badmotorfinger was the song “New Damage.” An even more interesting version of the song emerged later, thanks to a boost from Queen guitarist Brian May

Cameron: [There was a version of “New Damage] that was done for a compilation record where the producer was grouping together young bands with established huge rock stars like Brian May. I was a huge Queen fan. I’d say I was the biggest Queen fan in the band. Kim and Ben not as much. I saw Queen when I was like 16 years old. Thin Lizzy was opening up. It was fucking life-changing.

Shepherd: We shipped the tapes over to him. So that was the one non-solar-powered part of the thing, is having those tapes flown over to England for him to track.

Cameron: He came to Seattle once when we were rehearsing and at the time we were rehearsing where Pearl Jam was rehearsing when they first started. It was next to a blacksmith forge.

Shepherd: It was totally awesome. This rock aristocracy, walking down Crack Alley in Belltown, down the steps.

Cameron: Brian May shows up in a white limo with a white full-length leather coat. He comes down to our dingy, janky rehearsal studio, and he couldn’t have been more out of place, class-wise. He could not have been sweeter. Fully generous, sweet guy. He was completely up for collaborating, too.

Shepherd: This mean-ass dog named Junkie, that only liked us and his owner, he liked Brian May. He was a mean ass dog, man. A big bull mastiff. He looked like a black panther.

[embedded content][embedded content]

IX: With the recording process wrapping up, the band had two questions left to figure out. What were they going to call their new record? And what was the cover going to look like?

Thayil: Trying to name the album, I remember coming into the control room and saying to Chris, “Hey, how about I’m Okay – Urinal Cake?” The reference being [the 1967 self-help book] I’m Okay – You’re Okay. That made everyone crack up, but it was too much of a one liner. It didn’t have beauty or power. It was just funny. So that rolled around in people’s heads for a few days, I’m Okay – Urinal Cake. Then during that session, I went and jammed with a friend of mine, and he was four tracking what I was playing on guitar. And up came that Montrose song of “Bad Motor Scooter.” I didn’t recognize it. I heard the intro with the guitar making motorcycle sounds and I go, “What is this song?” And my buddy said, “That’s ‘Bad Motor Scooter.’” I’d heard the title, but I hadn’t heard the song. And I go, “It might as well have been Bad Motor Finger to me.” And my friend just looked at me and raised his eyebrows and we started laughing. We thought that was funny. It was a mashup of Bad Finger, a band I loved, and then this song “Bad Motor Scooter,” a song I was unacquainted with, but I heard of the title. So out came Badmotorfinger. Bad Finger with a Motor in the middle, which made everything a little bit more punk rock, a little bit more muscle car-y. And it was colorful. It sounded good. Badmotorfinger sounds great. If you write it out, it looks cool. And it’s evocative of color and everything that we’ve sensed. So, the next day I went to the studio and I’m Okay – Urinal Cake is starting to fade now, because people are understanding that’s not a very serious title. And I walk in with Badmotorfinger. Everyone’s like, “That’s it! That’s great!” And then Chris was smiling. I remember him pulling me aside later in the day, rolling because, “You know, that worked on so many levels.”

Mark Dancy (Album Cover Designer): In 1989, Soundgarden played at St. Andrews Hall in Detroit and my band Big Chief opened for them. That’s how we met. We gave them all sorts of propaganda, like Motor Booty. Motor Booty was a satirical, underground comics and music magazine I put out. I started it so somebody would publish my art. Anyway, we went to Seattle in 1991 on tour. We played with TAD. Kim and Matt came to the show and afterwards they came up and asked, “Do you wanna do our record cover?” That’s all it was. No idea about what they were planning or anything. They just said, “This is the title, wanna do it?” I said, “Yeah!” and started sending them sketches while still on tour. I had more of an idea of a motorcycle kind of thing originally, but they said, “No, we don’t want that.” Mostly, I was talking to Kim. What it was coming to was Badmotorfinger; Bad middle finger. So, it was kind of a flip-off. There were all these different versions with a hand raising a middle finger. I was coming at it all these different ways, and finally, I managed to do it a jaggedy way, with an electrical thing. What the design really is, is 12 songs, 12 little middle finger hands. If you look at it, that’s what it is going around in a circle.

X: Badmotorfinger was finally released on October 8, 1991. By the middle of the decade, it reached double-platinum status and netted Soundgarden their second Grammy nomination for Best Metal Performance. The band hardly had time to stop and enjoy the fruits of their labors however before embarking on a massive tour supporting Guns N’ Roses, followed almost immediately by a month-long swing through America’s finest amphitheaters on Lollapalooza, where they were joined by their buddies in Pearl Jam.

Cornell (2011): Particularly around the Badmotorfinger period, this huge transition took place where commercial rock music was all bad commercial metal. It ruled the airwaves. It ruled MTV. It ruled record sales.

Cameron: We had four weeks off in two years, or something like that. That’s what it felt like anyway. We were up for it. We wanted to be there. We had all these really great opportunities. We weren’t as precious about opening for Guns N’ Roses [as some other bands]. Nirvana didn’t want to open for Guns N’ Roses. I understand that they were asked first and then they asked us. I think they asked Pearl Jam too and those bands said “No.” We were like, “Hey man, our record’s great. We really love our record, and we want to just go out there, play some shows.” The Guns N’ Roses thing was kind of weird because it definitely wasn’t our crowd. On days off we would always do our own shows. We’d do a club show here and there, things like that. It was fun to see how our audience was getting bigger around ’91.

[embedded content][embedded content]

Granlund: I remember I was in New York with my girlfriend, and we were walking down the street one day and saw this poster: “Guns N Roses!” and “Soundgarden” in little letters near the bottom. So, I called Madison Square Garden and said, “I’m Scott and need to talk to Matt Cameron.” Eventually, I got through and said, “Hey, I’m in town!” and he goes, “Well, shit, go rent a saxophone!” Rented a saxophone in Greenwich Village and ended up playing the show with them. Hanging out backstage was kind of fun. Joey Ramone and one of his band members showed up, along with his girlfriend in a tiger stripe bikini. Then Joey and Chris started talking. It was kinda noisy in the green room, so those guys crawled underneath this big table and just hung out and had this long conversation. The two shy vocalists hiding under this table talking about the weird shit they drink.

Cameron: ’92 is when we did Lollapalooza. That’s where I felt like we really came into our own as a live band. Being part of that tour was really great because everyone was peaking at the same time.

Shepherd: God, that tour. That was emotionally heavy. I don’t know. It was a fun time. Over the years, everyone always said that was the one Lollapalooza that gelled the most. The bands interacted the most. It actually worked the way it was supposed to be. I just remember getting in a lot of Goddamn trouble on that tour, doing really stupid stuff, that I could have been either killed, or arrested for. I wrote a lot of Hater songs on that tour.

Thayil: There was always a strong sense of camaraderie. Lollapalooza the tour, annoyed me. I don’t know, I guess the cesspool environment, just so many bands and so many other people. Too many people. There’s something irritating about it. But the great takeaway was we made some friends for life out of the Jim Rose Circus Sideshow guys. The pyrotechnic for Red Hot Chili Peppers was a Seattle guy and we became close friends for a number of years. There was certainly the camaraderie and bonding with the Pearl Jam guys, to see them having success.

Cameron: It was cool to see these younger bands all fucking just grabbing at the ring at the same time. It was interesting to see the Pearl Jam crowd increase during that tour. They were the second band, I think they were, the second band on the bill. I think we were like the fifth band or something like that. It was really fun to watch the crowd just running to get their place to see Pearl Jam. It was really cool.

[embedded content][embedded content]

XI: While it goes without saying that the members of Soundgarden have a lot of pride for each of their albums, it’s clear that Badmotorfinger occupies an especially cherished space that’s only grown as the years have gone by.

Thayil: It’s amazing for the longest time, Superunknown was the album that was referenced because it was the most commercially successful. The band would often reference — well, Matt would often reference Screaming Life — but for the 25th anniversary box set and I just became reacquainted and familiarized with the material. I started hearing things I hadn’t heard in many years and Badmotorfinger all of a sudden was at the forefront of my mind and it stayed there. Since then, I’ve heard many people refer to it as their favorite album. So that’s cool that it’s surpassing the one that received accolades and commercial success in its day.

Date: That’s one of my favorite records that I’ve done.

Cameron: It still sounds relevant. A lot of that has to do with the fact that the music was really meaningful to us as musicians and as a band. I don’t really listen to the records that much anymore, but if I have my phone on shuffle mode and I’m driving in my car, something comes up from Badmotorfinger, it just sounds really cool. It has a personality. I think that’s what we were aiming for. We didn’t really ever sit down and talk about what it all meant in the history of music at the time we were so busy doing it. Now that I’ve had some time to reflect, I’m really proud of the fact that my band Soundgarden was part of a really important shift in rock music at that time, and music in general. The early ‘90s, there was a lot of breakthrough genres that happened all at the same time. I’m really proud of my generation. I’m really proud of those records.

Shepherd: I lived in a little rental house, in Winslow and every day I would listen to Double Nickels on the Dime [by Minutemen] and I’d listen to this one Duke Ellington record. So, when I finally got that album, I held it while looking at Double Nickels on the Dime on the kitchen table, and that Duke Ellington record. It was like, “Wow, these two records helped make this record,” and I held onto it. I think that was the best record that I’ve been part of. Like the gates were opened, and we hit the ground running. The leopard got its spots and booked it.

[embedded content][embedded content]