“If I could fake it, honestly I would,” goes the refrain on Tom Walker’s latest single, Freaking Out.

It’s a window into the anxiety that leaves him feeling isolated and alone, even in a room full of friends.

“I’m a little past being out of my depth,” he confesses.

When the Scottish singer uploaded the song to TikTok last year, it immediately touched a nerve.

“Story of my life,” wrote one fan. “As someone recently diagnosed with autism and ADHD, this is spot on,” added another.

“It’s just so powerful,” said a third. “I’m not diagnosed with anything but I always feel like this – putting off going out with friends and losing friends because of it.”

Freaking Out never made the top 40, and its streaming numbers aren’t within shouting distance of Walker’s biggest hits, Leave A Light On and Just You And I.

But comments like those matter more to him than chart statistics ever could.

“One of the most beautiful things as a songwriter is when people feel the song is written for them,” he says. “When you see people in the front row bawling their eyes out, it’s mad that the connection to music can be that deep.”

The reaction is even more meaningful because, for a long time, Walker had lost that relationship with music.

‘Zoom writing sessions are the worst’

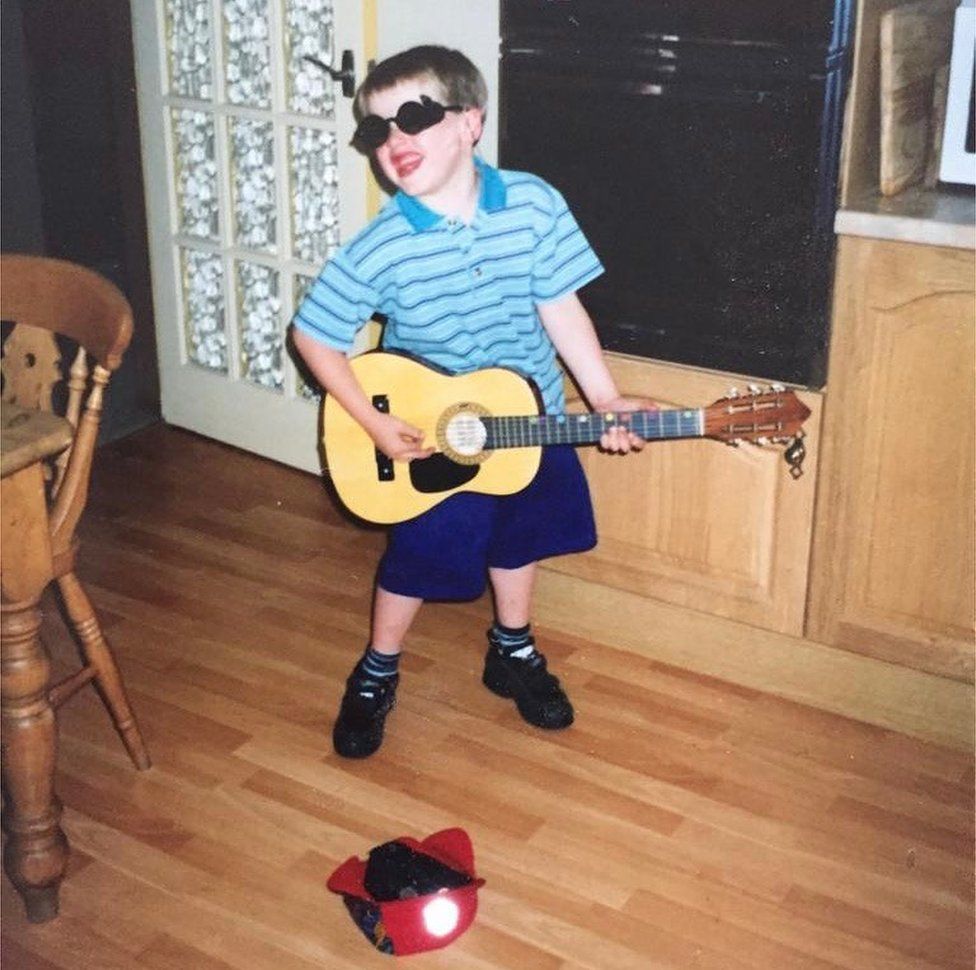

Born in Kilsyth, North Lanarkshire, but brought up in Knutsford, near Manchester, he spent his childhood listening to records with his father, devouring classics by Ray Charles, The Police and Foo Fighters.

After teaching himself to play drums, guitar, piano and bass, he studied songwriting at London’s College of Contemporary Music, and began releasing his own material in 2016.

Back then, he was making ends meet by working part-time as a photo-booth operator and distributing leaflets on cycling safety for London Transport – but life changed quickly.

In 2017, the influential New York DJ Elvis Duran chose Walker as his “artist of the month”, earning him a slot on NBC television’s Today Show.

A year later, the powerful, hip-hop infused anthem Leave A Light On charted around the world; his debut album, What A Time To Be Alive, sold three million copies; and Walker won best breakthrough artist at the Brit Awards.

The pressure was on to write a follow-up, and fast. Then the pandemic hit.

“Do you know what I should have done?” he says. “I’d just spent five years touring a very successful album, I hadn’t seen friends, I’d barely seen my missus. I should have just taken some time off. And instead I was like: ‘Oh, my God, I need to write this next album’.”

Locked indoors, he tried to set up online writing sessions, but the experience was brutal.

“Five hours on a Zoom call. It’s the worst thing you can imagine. Somebody would sing a melody, and you’d sing it back with an amendment, and it just went on for so long.”

He found himself rushing through sessions, desperate for the moment he could click “end this meeting”. When his record label heard the results, they weren’t happy. Neither was he.

“I binned an album’s worth of stuff,” Walker says. “I lost my way with music. I fell out of love with it during that process.”

Things began to improve once the world opened up again, but Walker’s re-entry wasn’t without problems. His first gig back was a socially-distanced outdoor event, with fans herded into square boxes painted on the grass and kept 20 feet apart.

Although he’d practised “more than for any other gig I’ve ever done”, he ended up experiencing the beginnings of a panic attack: “I went out on stage and messed up a load of the lyrics. I completely fluffed it.”

Over the next year, he released a handful of singles, including the protest song Number 10, fuelled by his anger over the “partygate” scandal; and The Best Is Yet To Come, a romantic tribute to his long-term girlfriend, Annie Watson-Foulds, whom he married in April 2023.

Dark stories

It wasn’t until last spring that he finally hit his stride. Struck by a sudden burst of inspiration, he wrote the bulk of his second album, I Am, in just three weeks.

The new material is more gritty and percussive than the Walker of old. There’s a dizzying sense of scale in the record’s multi-stacked vocals and plunging electronic basslines, but the musical firestorm never obscures his humanity.

The singer calls the album “depressing with an undertone of hope”, and he certainly goes to some dark places, lyrically.

Burn is an angst-ridden riposte to the record label executives who “had a dig” at his earlier material, while Head Under Water is a what-doesn’t-kill-you anthem about overcoming panic attacks.

But the song that really snatches your breath is Lifeline, written after Walker suddenly and unexpectedly lost a close friend,

“I wish we could have saved you,” he laments over muted piano chords. “Pray to God you would have reached out and given us a chance to change your mind… I wish you knew you had a lifeline.”

Walker was hesitant about releasing it. He agonised that it would dredge up all the pain and grief, and force the people who’d been affected to live through it again.

And he questioned whether a song could genuinely make a difference. He’d seen how people reacted to Leave A Light On – written for a friend dealing with drug addition – but felt that simply presenting a message wasn’t enough: “It’s all good and well doing a gig and saying: ‘If you’re struggling, talk to your friends’, but not everyone’s got that option.

“That’s why, this time, I want to team up with the Samaritans or Calm so that, when I am talking about this stuff, I can say: ‘Here are the people who are qualified to offer the right advice’.”

The song will be included on his album, with the blessing of his friend’s family: “I came to the conclusion that these experiences are important to talk about, as long as it doesn’t upset the people who are directly involved.”

When you’re writing about topics this raw it’s easy to slip into humourless sanctimony, but Walker’s music is located in compassion, always finding nuggets of hope and happiness in the darkness.

It’s a reflection of his character. He acknowledges his second album blues with good humour, and approaches the future with cautious optimism.

When he talks about his wife, his face lights up. She’s a “guardian angel”, he says, who met him on a ski trip, fell in love with his dubstep dance moves (“I’d been skanking hard”) and then stuck by him while he spent years as a penniless musician.

They spent Christmas watching the Die Hard movies in the wrong order, as he gears up for a proper return to the spotlight in 2024.

With a five-year gap since his first album and “no top 20 hits in a while”, he worried his audience would have vanished, but the fears were misplaced. A headline tour in April has already sold out in four cities, with extra dates being added all the time.

And, true to his beginnings in cycling safety, he’ll arrive at many of those venues on two wheels.

“There’s loads of places you can’t drive in a massive double-decker bus,” he explains. “So if you need to nip to the shops, it’s useful to have some scooters chucked in the back. I can’t wait.”