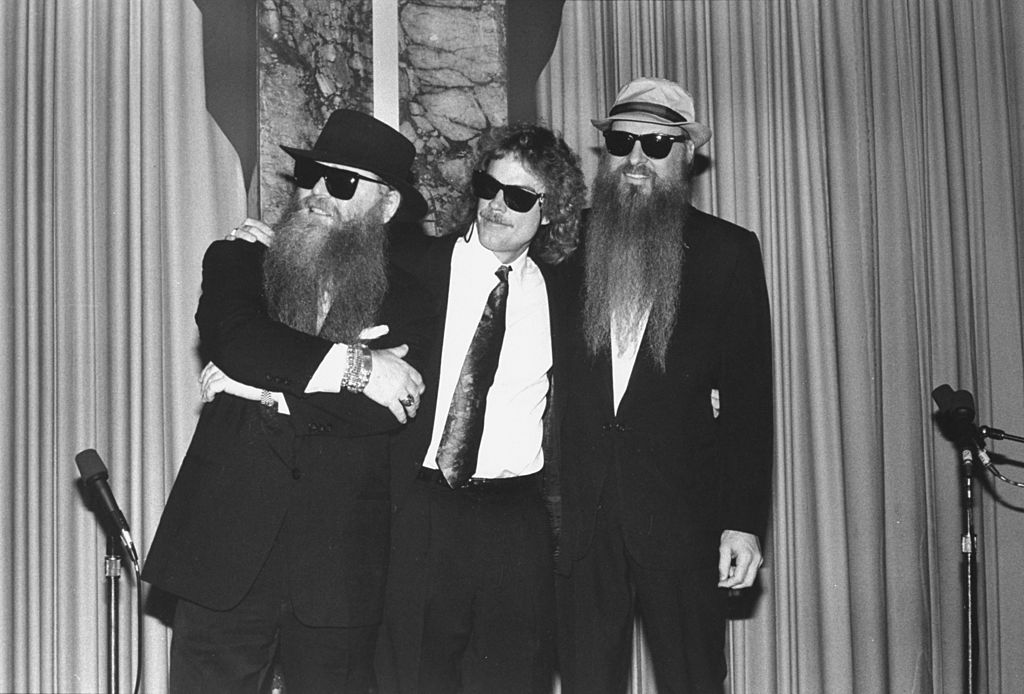

A version of this story was originally published in the February 1991 issue of SPIN. In light of Dusty Hill’s passing, we’re republishing it here.

Overheard speaking in the nasal twang of the Great Southwest, during the finale of a ZZ Top concert:

“Well, talk about your everlovin’ son et lumiere! Hot damn, Vietnam!”

The speaker, standing just behind me, was a lank and leather-skin English professor from the University of Texas. We had exchanged a few words earlier, when he had remarked of the similarity of the ZZ sound to that of the Rolling Stones, in such a way as to invite my response, which I didn’t deny him:

“It’s probably safe to say,” I ventured in my most scholarly tones, “hurmph, hurmph, that they both come from the same bag, but have remained distinct … if you garner my innuendo.”

He did indeed, or so it seemed, because he then proffered a small softly glowing brass pipe, which proved to be the source of an aroma I had previously noticed but failed to locate, namely smoldering cannabis, or “the damnable wog-hemp” as it is perhaps more frequently called. Not wishing to appear unsociable (and for no other reason since I avoid like the plague any derangement while on the job—and especially for a stickler like SPIN mag) I had a child’s portion toke. It was heady stuff all right, and it lent itself absolutely to what was coming down on stage, where, against a mountain of wrecked cars, rocking precariously, and junked TV sets, screens still in their strobe death throes, three crazy galoots—two of them demonic, larger-than-life gray-bearded gnomes—cavorted to their own pile-driving frenzy of high-powered nonstop rhythm and blues, at a decibel level quite beyond anything ever achieved, or perhaps contemplated, by the Stones.

The Stones-Top comparison is not, of course, inappropriate. ZZ Top has mastered the Stones’ format of opening a number with a roar—and then building. Where the comparison between ZZ Top and the Stones, or any other group, ends is the ungodly response they generate from the crowd, which can only remind one of mega-amplification of the first audiences of The Rocky Horror Picture Show. I was standing (no one sits at a ZZ Top concert) behind the sound-control box and had to marvel at the number of times the engineer broke up, laughing at having completely “lost them” on the panel, because the volume was above registration.

“Outta state, man!” he would yell in delight, gyrating to the monstro beat.

All this was happening recently at the St. Louis Arena. We were now sitting backstage in the Reception Room, all relaxed and informal, but I still had a job to get on with, so I began to query them about the origin of the name they chose to call themselves, “ZZ Top.” I had already been assured, rather emphatically, by their hefty press agent, that it did not stand for Zig-Zag cigarette papers. “No way, Jose,” he said tersely. “These are clean-living boys. End of story.” You bet. Ho-hum.

“I have reason to believe,” I said to them now directly, “that ZZ Top’ was something out of your childhood—like Rosebud in Citizen Kane. In fact, I recall now how in my own Texas youth every boy owned a wooden top. These tops had steel spindles which we sharpened and then played a game like marbles, but using beer caps, which had different values, according to brand. I remember that the most valuable brand was one called Black Dallas. The object was to knock the caps out of a circle with the spinning top. If a top stayed inside the circle, the other players could hit it with their tops, and with luck could split it in two—which was the highest achievement possible in the game.”

“Far out,” said Frank.

“Well, is it possible that your favorite brand of top was called ZZ?” I wanted to know.

“I guess the whole top thing was before our time,” said Dusty, in a wet-blanket shut down of my number one theory.

“Then that leaves only one conclusion,” I suggested, “that `ZZ’ comes from the French word ‘zi-zi’ which, I am sure you know, means something like ‘pussy.’ You know how French hookers are always saying, `Voulez-vous faire zi-zi avec moi?‘ Do I hear a “touché“? Am I getting warm?”

Billy Gibbons, who I believe is tacitly designated to handle the heavier bottom-line type queries, just smiled. “Nope,” he said. And that would appear to be that.

My first exposure to the extraordinary power rock-boogie of ZZ Top occurred in the so-called “Smoking Section” compartment of the Rolling Stones 1978 tour plane. Bobby Keys, the great shake-tail tenor saxophonist who was part of the band, was about to play one of their early tapes for Keith Richards. “These are good ol’ boys,” he explained, “they are real down-home shit-kickers.”

“Are they heads?” Keith wanted to know. Keith was suspicious of anyone who was not into some form of sense derangement.

“Abso-fucking-lutely!” Bobby assured him. “They were weaned on ‘Tex-Mex loco-weed!”

This seemed to satisfy Keith; he snugged his earphones, and flipped the volume to full.

When I told Billy Gibbons about this incident of yesteryear, he smiled.

“Keith Richards has been our main man for a long time,” he said. “We got a lot from the Stones.”

“As much as you got from Muddy Waters and Little Richard?” I asked, with a dumbbell grin.

“Well, now you’re talking seminal sources,” he said.

This rang a bell with Frank and Dusty. “Hey, has that got anything to do with my ‘precious bodily fluids’?” one of them demanded, in the put-on twang of the cowpoke galoot, and added a big “Haw-haw!”

We were still in the Reception Room, where fans congregate after each concert, hoping to receive a visit from their heroes—who do, in fact (and bless them for it), almost always put in an appearance. Having observed, exhilaratingly close up, the man-eating antics of the Stones’ groupies, I was intrigued by the disciplined reverence displayed by the devotees of ZZ Top. Not that the girls weren’t provocative. On the contrary, many were ultra-fabs, dressed, despite the coolness of the November evening, in minis, micros, and short-shorts, with top-of-the-line pert knockers and rounded derrieres in abundance, and displayed to grand advantage.

“My guess is,” I said to my three hosts, giving them a straight look, “that you guys get more ass than a toilet seat,” and added my practiced hurmph to assure them it was a legitimate line of research-inquiry.

“Well now damned if that don’t take the rag!” said Gibbons with an exaggerated show of annoyance.

“You’re talkin’ kiss an’ tell, mister,” said Dusty in a stern manner.

Frank, who looks sort of like a matinee idol, whose specialty is villains, was not so reluctant. “Stop around later,” he said, with a lascivious wink, “I’ll give you the lowdown. I don’t want to embarrass these two. They can get mighty jealous.”

“And mighty mean, too, hoss,” Billy reminded him, with a scowl that would have made lesser men tremble.

The ZZ sense of humor is, of course, widely celebrated, and not without good reason.

It is their humor, in fact, which is the key to their extraordinary visual appeal. The spectacle of what appears to be two sly-looking Rip Van Winkles, wearing Jack Nicholson shades and doing a boogie shuffle is so utterly incongruous as to be at once hilarious. It is classic visual comedy, reminiscent of great lost moments of timeless farce of stage and screen—like some of the earliest Keystone films, where a story would be unfolding quite conventionally and then the scene is suddenly zapped by the abrupt arrival of a grand eccentric—precisely like an old bearded man, wearing dark glasses (Is he blind? Even funnier) and dancing like one of the Blues Brothers, or ZZ Top. The image reminded me at once of a great moment in theater I had witnessed a few years back. It was a piece about Howard Hughes, played by another great Texan, Rip Torn, wearing a Hughes (or ZZ) length of gray beard and shades. In a scene of solitary and poignant self-revelation, the character (Hughes) put each foot into a Kleenex box (Hughes was possessed by a Kleenex/cleanliness fetish); and then this ancient and fragile billionaire gravely proceeded to execute a rhythmic soft-shoe boogie shuffle. It broke up the house.

Now, in the Reception Room, I reverted to my own west-of-the-Pecos drawl to get a rise out of Gibbons. “Gol dang, Billy, is that where you got that move at? Took it off ol’ Torn?”

Hill and Beard had a good guffaw at the notion.

“Why, hell no!” Gibbons fairly bellowed, then calmed down. “I like ol’ Torn, but that is my move. I don’t know where I got it. I reckon I just snuck up on it. Hee-hee.”

Wittingly or not, Gibbons and Hill have captured that elusive strain of absurd incongruity which comes with the totally unexpected or unprepared for. Not only do they have this great shuffle choreography going, they have also mastered all the classic old hip “ax manipulations” of Slim Guillard, and even a few of Jimi Hendrix as well. (A curious, and somewhat historic, footnote in that regard is that Billy Gibbons actually owns one of Hendrix’s guitars [Fender Stratocaster], given to him during their friendship. A guy comes up to him and says: “Hey man, I hear, you got Jimi’s ax! Outta state!”

“‘Tell me about it,” says Billy.

Later, when I asked Gibbons about the humorous aspect of the ZZ presentation, he smiled and said: “When white boys try to play the blues, it better at least be funny.” Ultra-hip Billy G. And it has rubbed off on his sidekicks.

Dusty Hill was raised in Dallas (as was a certain yours truly) and he frequented an area which I knew well—Central ‘flacks, or in the official vernacular of the Dallas police, “N—r Town.” It was the place to go for barbecued ribs and chicken, or to hear the kind of music (like Little Richard) not always available elsewhere. And there were the great pre-Aretha rock spiritualists to be heard—Mahalia Jackson, Marie Knight, and Sister Rosetta Thorpe. The record store in Central flacks featured the exotic labels—Chess, Cat, Black Cat, and Rooster. Elsewhere they might be called “race records”: here they were simply 78s or 45s and brought to prominence such fountainheads of rock-blues-boogie as Lightning Hopkins, Willie Mabon, Joe Liggins and His Honeydrippers, Andy Kirk and His Clouds of Joy (so called because of their rather straightforward bandstand substance abuse), and Big Daddy Brown, whose smash single was called “Big Ten Inch Record” and featured the following spunky verses:

My gal don’t go fer smokin’

Liquor jest make her flinch

Seems she don’t go for nothin’ …

Except my big ten inch …

Record of the band that play the blues

Last night I try to tease her

I give her a little pinch

She say, “Now top that jivin’

An’ git out yoah big ten inch …

Record of the band that play the blues”

She jest love my big ten inch

Record of her favorite blues.

In short, it was a magical place, in a magical era—ideal for a 15-year-old Dusty Hill to learn to jump a blues.

I asked him how he happened to choose the bass guitar as his instrument.

“Not so much my choice,” he drawled, “as my big brother, Rocky’s.”

“Rocky Hill?”

“Yep. Him and his friend, Joe Bob Junior. You see, Rocky already had a guitar, and Joe Bob Junior had a set of drums. So I got the bass. Never regretted it.”

“Let me ask you something, Dust. Do you think that, over the years, you’ve gotten as much poon as you would have playing regular guitar? Or drums for that matter?”

“Better quality” he replied without missing a beat. “I don’t know why it is, but your bass guitar always gets the ace poon. Ask Bill Wyman.”

He may have something there. Wyman’s women are consistently 25 years his junior, and always ultra-fabs.

Dusty started playing with pickup bands from around town—beer-joint gigs with his brother and the drummer. Sometimes his mother would chaperone since they were all about 13 or 14. By the time he was 15 he and Rocky were working steadily with a band called the Deadbeats. The group mutated, during the British craze of the mid-’60s, into Lady Wild and Her Warlocks. After they lost their fab vocalist (to a Bill Wyman type) they met up with the dynamic Frank Beard and formed the American Blues—a group which had regular gigs until it broke up in 1968. Hill was 19 and he moved to Houston. By a quirk of fate, Frank also headed for Houston after the disbanding, though neither was aware of the other’s move.

“You guys must have been out of your gourds,” I suggested, “not telling each other where you were headed.”

Dusty yawned. “I reck-tum,” he said.

Meanwhile, in another part of town, Frank had met up with, of all people, Billy Gibbons; he joined the band Billy was playing in.

“So there we were,” said Dusty, “working about six miles apart and not knowing it. Downright weird.”

“It was weird, and that’s a fact,” said Frank. “Then one night I heard about this ba–ad bass guitar, in a band across town. The guy who told me was a guitar player. He said: ‘The dude laid down a couple of tricky riffs, but he was playing this funny-looking Gibson, so I figured he was all hat and no cattle. Then I got up on the stand with him. And, Frank, he blew me away.’ Well, that sounded like somebody I just might know, so I headed across town pronto.”

And, of course, what ensued was, hurumph, hurumph, historic—Dusty’s reunion with Frank, and then his first meeting with Gibbons.

“We started cooking,” recalls Dusty, “and went right through the night.”

Frank Beard is the normal-looking one of the three. In fact, he has the build and grace of a great natural athlete, so I was not too surprised to learn that he had been the star quarterback of the ass-kicking high school football team of Irving, Texas, a hamlet-sized suburb of Big D and not far from my own Sunset High in Oak Cliff.

“Is it true,” I asked him, “that your very popular song ‘La Grange’ is in homage to a whorehouse?”

“Yes,” he beamed. “It’s in praise, or celebration, of a very famous bordello outside Austin—immortalized on stage and screen as The Best Little Whorehouse in Texas. It was a noble and beloved institution—destroyed by an ambitious and unscrupulous DA.”

“I remember the case,” I said, “the people of the state seemed to be in sympathy with the ‘institution’ and against the DA. Right?”

“Hell yes,” said Beard. “So much so that the old ex-sheriff of that county punched out the DA—after tearing his wig off.”

“Only in Texas. Right, Frank?”

“You bet your A,” said Frank.

Later that evening we were in one of their hotel rooms, just doing the hang and reminiscing about the good old days along Central Tracks in Big D. Earlier I had recited the lyrics of the “Big Ten Inch Record” for Frank, and he insisted I repeat it for those two great connoisseurs of such good Tex stuff, Gibbons and Hill—which I did, in my best Billy Eckstine/Joe Turner fashion.

“We ought to do that tune on the show, ” said Frank, laughing at the idea.

“We have to be more subtle,” said Dusty. “‘Tube Snake Boogie’ is about as far as we can go.”

“What about your line ‘You can bring the six, I’ve got the nine’?” I asked. “Isn’t there a bit of subtext going on there?” They chose to ignore my query.

The last time I was around that Central ‘flacks area,” said Billy, “a great thing happened. I walked into this almost empty bar, and a beautiful chick was singing, leaning against the piano really belting it out. Terrific voice. So I made my way to a table, sat down, and listened. When she finished the song, she reached behind her, tied on an apron and came over. ‘What’ll you have?’ It was beautiful.”

This reminded Dusty of other bygone days. “You know one of the earliest memories I have of some really pure, simple, black singing was over the Del Rio Texas X radio station. Some beautiful gospel singing. Remember?”

“Everything,” said Billy. “That station had everything. Country and western. Mexican. Rhythm and blues. Holy Roller church music. Everything. I used to turn it on around six in the evening. First you’d get the farm-produce news. Hog futures, that kind of thing.”

Frank perked up. “And then Dr. Brinkley would come on with his Goat Gland Rejuvenation Medicine. I loved the ads on that station. I’d like to get a tape of all those ads. They were out of sight. What an education.”

Billy turned to me. “I’ll tell you about a funny experience we had in Del Rio,” he said. “You know, Del Rio is not really in Texas. They call it Del Rio, Texas, but. it’s actually just across the border, in Mexico. That’s why they can get away with all that Goat Gland stuff, because it’s not subject to American law. Anyway, the three of us went into this Mexican bar and there was a little band playing there. Well, we had a few drinks and decided we’d like to sit in with the band. We asked the guy, the owner, and he said, ‘Sure, it’ll cost you three dollars each. We rent you the guitars.’ Well, that was cool, we’d just been paid, so they give us guitars and we sit in with the band. And we’re blowing up a storm, getting a lot of encouragement from the regular members of the band, you know, ‘Olé! Go man, go!’ and so on. So we’re feeling real good about it, wailing away, getting some ego charge from the encouragement of the regular band, like that. Then when the band stops and it’s time to go, the guy says, ‘Okay, that’s thirty-six dollars.’ Turns out it, was three dollars per tune! No wonder they were encouraging us to play more!”

They all break up at the recollection. “‘The three-dollar misunderstanding,’” said Frank.

Well, let’s talk a little more about the Stones,” I said. “I’ve read that you consider them to be one of your strongest influences.”

“We could talk forever about the Stones,” said Dusty.

Frank laughed. “When the Stones stopped playing for a while, we said, ‘My God, no more Stones records! What are we going to steal from?’”

Billy chuckled. “So we had to start doing our own thing.”

“I’d say you’re doing very much your own thing now,” I said. “It’s totally unlike anything I’ve ever heard. It’s definitely your own, and the really great part is that you go all out. And that is unusual. And I am convinced it is why you have finally made it so big, and on your own terms.”

After a pause to muster my courage I said, “And now something I feel I must ask you is, why the costume? Why the beard, and the cap, and the shades? It’s as though you wanted to build an impenetrable wall around yourselves.”

“It was an accident,” said Billy. “When we laid off work for three years, we just didn’t bother to shave. Then when we finally came in to sign our new record contract, we had beards, and we just happened to be wearing shades that bright day. So the record company guy says, ‘Hey, we’ve been thinking about how to build an image for you guys, and what kind of image. But why don’t you just cool it until we come up with something.”

“So we cooled it,” said Dusty. “Just didn’t shave.”

“But we started working,” said Frank.

“And now everybody is used to it,” said Dusty, “and so are we.”

“Now we couldn’t change if we wanted to,” said Billy.

“Now they’re stuck with it!” said Frank, with a grand guffaw—which no one failed to appreciate.