On Monday, Dana Simmons came downstairs to find her 12-year-old son, Lazare, in tears. He’d completed the first assignment for his seventh-grade history class on Edgenuity, an online platform for virtual learning. He’d received a 50 out of 100. That wasn’t on a practice test — it was his real grade.

“He was like, I’m gonna have to get a 100 on all the rest of this to make up for this,” said Simmons in a phone interview with The Verge. “He was totally dejected.”

At first, Simmons tried to console her son. “I was like well, you know, some teachers grade really harshly at the beginning,” said Simmons, who is a history professor herself. Then, Lazare clarified that he’d received his grade less than a second after submitting his answers. A teacher couldn’t have read his response in that time, Simmons knew — her son was being graded by an algorithm.

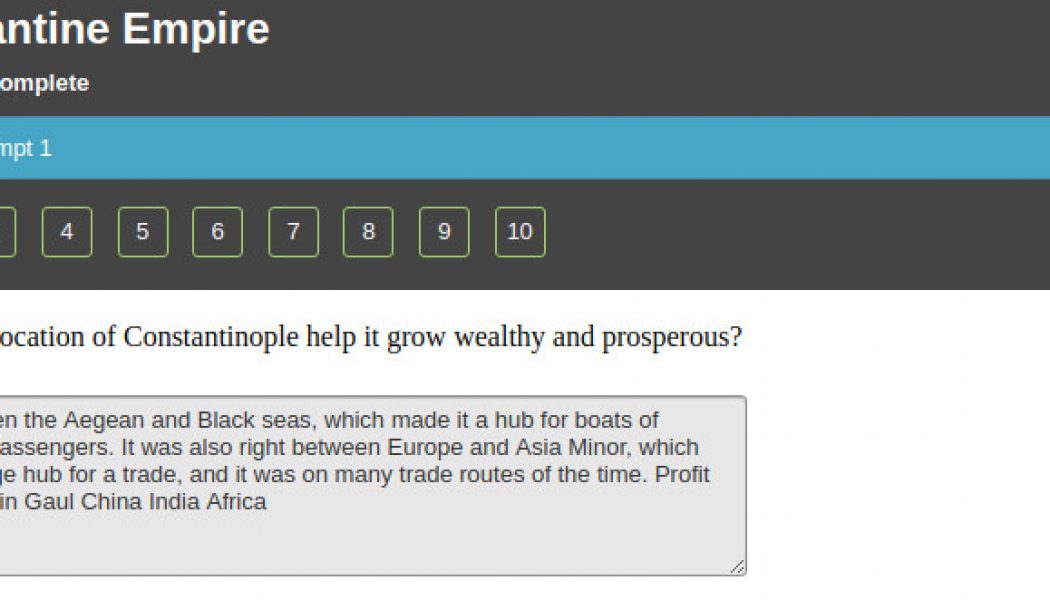

Simmons watched Lazare complete more assignments. She looked at the correct answers, which Edgenuity revealed at the end. She surmised that Edgenuity’s AI was scanning for specific keywords that it expected to see in students’ answers. And she decided to game it.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21848539/ss_2.png)

Now, for every short-answer question, Lazare writes two long sentences followed by a disjointed list of keywords — anything that seems relevant to the question. “The questions are things like… ‘What was the advantage of Constantinople’s location for the power of the Byzantine empire,’” Simmons says. “So you go through, okay, what are the possible keywords that are associated with this? Wealth, caravan, ship, India, China, Middle East, he just threw all of those words in.”

“I wanted to game it because I felt like it was an easy way to get a good grade,” Lazare told The Verge. He usually digs the keywords out of the article or video the question is based on.

Apparently, that “word salad” is enough to get a perfect grade on any short-answer question in an Edgenuity test.

Edgenuity didn’t respond to repeated requests for comment, but the company’s online help center suggests this may be by design. According to the website, answers to certain questions receive 0% if they include no keywords, and 100% if they include at least one. Other questions earn a certain percentage based on the number of keywords included.

Algorithm update. He cracked it: Two full sentences, followed by a word salad of all possibly applicable keywords. 100% on every assignment. Students on @EdgenuityInc, there’s your ticket. He went from an F to an A+ without learning a thing.

— Dana Simmons (@DanaJSimmons) September 2, 2020

As COVID-19 has driven schools around the US to move teaching to online or hybrid models, many are outsourcing some instruction and grading to virtual education platforms. Edgenuity offers over 300 online classes for middle and high school students ranging across subjects from math to social studies, AP classes to electives. They’re made up of instructional videos and virtual assignments as well as tests and exams. Edgenuity provides the lessons and grades the assignments. Lazare’s actual math and history classes are currently held via the platform — his district, the Los Angeles Unified School District, is entirely online due to the pandemic. (The district declined to comment for this story).

Of course, short-answer questions aren’t the only factor that impacts Edgenuity grades — Lazare’s classes require other formats, including multiple-choice questions and single-word inputs. A developer familiar with the platform estimated that short answers make up less than five percent of Edgenuity’s course content, and many of the eight students The Verge spoke to for this story confirmed that such tasks were a minority of their work. Still, the tactic has certainly impacted Lazare’s class performance — he’s now getting 100s on every assignment.

Lazare isn’t the only one gaming the system. More than 20,000 schools currently use the platform, according to the company’s website, including 20 of the country’s 25 largest school districts, and two students from different high schools to Lazare told me they found a similar way to cheat. They often copy the text of their questions and paste it into the answer field, assuming it’s likely to contain the relevant keywords. One told me they used the trick all throughout last semester and received full credit “pretty much every time.”

Another high school student, who used Edgenuity a few years ago, said he would sometimes try submitting batches of words related to the questions “only when I was completely clueless.” The method worked “more often than not.” (We granted anonymity to some students who admitted to cheating, so they wouldn’t get in trouble.)

One student, who told me he wouldn’t have passed his Algebra 2 class without the exploit, said he’s been able to find lists of the exact keywords or sample answers that his short-answer questions are looking for — he says you can find them online “nine times out of ten.” Rather than listing out the terms he finds, though, he tried to work three into each of his answers. (“Any good cheater doesn’t aim for a perfect score,” he explained.)

Austin Paradiso, who has graduated but used Edgenuity for a number of classes during high school, was also averse to word salads but did use the keyword approach a handful of times. It worked 100 percent of the time. “I always tried to make the answer at least semi-coherent because it seemed a bit cheap to just toss a bunch of keywords into the input field,” Paradiso said. “But if I was a bit lazier, I easily could have just written a random string of words pertinent to the question prompt and gotten 100 percent.”

Teachers do have the ability to review any content students submit, and can override Edgenuity’s assigned grades — the Algebra 2 student says he’s heard of some students getting caught keyword-mashing. But most of the students I spoke to, and Simmons, said they’ve never seen a teacher change a grade that Edgenuity assigned to them. “If the teachers were looking at the responses, they didn’t care,” one student said.

The transition to Edgenuity has been rickety for some schools — parents in Williamson County, Tennessee are revolting against their district’s use of the platform, claiming countless technological hiccups have impacted their children’s grades. A district in Steamboat Springs, Colorado had its enrollment period disrupted when Edgenuity was overwhelmed with students trying to register.

Simmons, for her part, is happy that Lazare has learned how to game an educational algorithm — it’s certainly a useful skill. But she also admits that his better grades don’t reflect a better understanding of his course material, and she worries that exploits like this could exacerbate inequalities between students. “He’s getting an A+ because his parents have graduate degrees and have an interest in tech,” she said. “Otherwise he would still be getting Fs. What does that tell you about… the digital divide in this online learning environment?”