Biden himself gets that, said Jason Walsh, executive director of the BlueGreen Alliance, an organization of labor unions and environmental groups jointly working on environmental issues. He said Biden understands the value of the labor movement within the transition to a clean energy economy, and highlighted proposals in Biden’s infrastructure plan unveiled last week to beef up clean energy job quality.

“His understanding of labor, I think, extends to knowing intuitively that you can’t expect workers and their representatives to embrace this transformation if they can’t continue to get work that will pay family-sustaining wages and benefits and be a career,” Walsh said. “The reality is that there is so much work that will be created by this transformation that it is just imperative that we get the job quality piece right.”

Energy workers on the whole earn more than the typical American, but the highest-paying positions are skewed heavily toward nuclear, utility and natural gas and coal industry workers, the new data show. The wind, solar and construction jobs that would surge under Biden’s policies were well below them on the median pay scale.

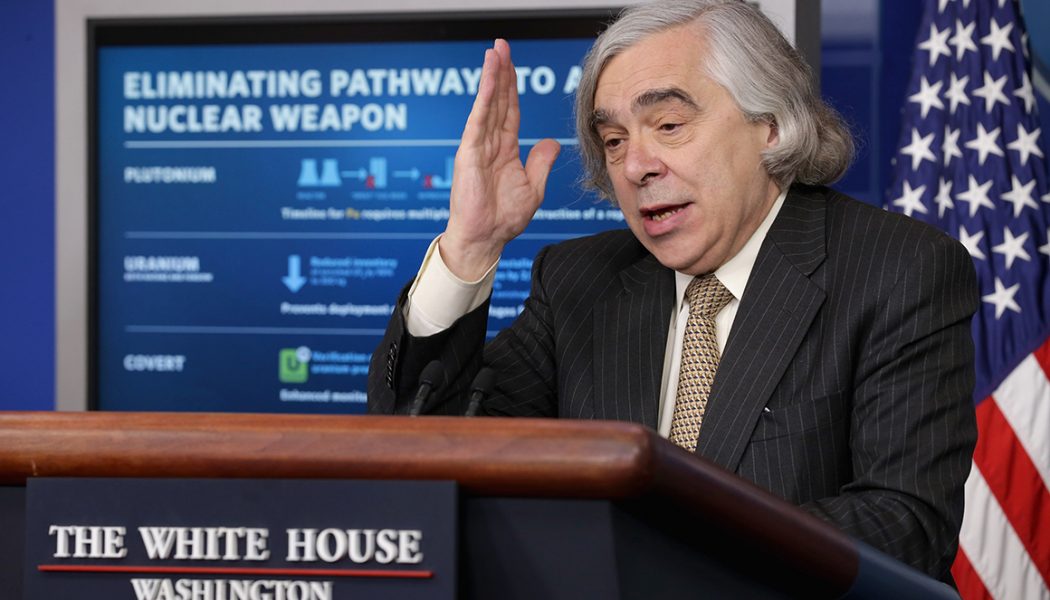

“The big message is that the energy industry has a significantly higher median wage than does the economy as a whole. That’s very important,” Moniz, who led the Energy Department during former President Barack Obama’s second term, told POLITICO. Still, he acknowledged, “There’s clearly a distribution of wages — as there is in any other sector — because of the level at which specialized skills are needed.”

Labor groups are already growing nervous that Biden’s plan will eliminate the kind of steady, fixed-location jobs provided by coal mines or fossil fuel power plants, and instead will lead to temporary construction jobs that require mobility. A second worry is that wind farms, solar plants and other climate-friendly power sources will need few workers to maintain them and keep them operating.

The prospect that workers would also receive significantly less pay can only add to Democrats’ challenges in persuading voters that their climate strategy is also a jobs strategy.

“For people that are in the fossil sector, the prospect of moving to the clean energy sector if you have to take a pay cut is not attractive,” said Brad Markell, the executive director of the AFL-CIO Industrial Union Council.

But, Markell added, the Biden administration’s plan unveiled last week has the elements to tackle the problem, including support for the Protecting the Right to Organize Act and strong labor standards attached to the extension of clean energy tax credits.

The bright spots: The median hourly wage for all U.S. energy workers is $25.60 — 34 percent higher than the national median hourly wage of $19.14, according to the data from Moniz’s Energy Futures Initiative. And while the energy sector has suffered during the Covid-19 pandemic, it has lost fewer jobs than other parts of the economy.

According to the report, utility employees were the highest paid among energy industry segments, with a median wage of $41.08 per hour, which would amount to nearly $85,500 per year, while mining and fossil fuel extraction workers followed at $36.32 per hour, or more than $75,500 over a year. The high concentration of utility jobs in the electric power generation and transmission, distribution and storage sectors also mean workers in those positions earn higher than average wages.

Jobs in energy-specific construction, which would get a major boost under Biden’s plans to modernize the power grid to accommodate new wind and solar power plants, pay about $25.53 per hour, or just above $53,000 for the year. Manufacturing jobs earned a median wage of $23.02, or nearly $48,000 for a year.

The new data is a supplement to the annual U.S. Energy and Employment Report that the Energy Department used to release, but which lapsed under the Trump administration. Moniz’s Energy Futures Initiative continued to work on that report in collaboration with the National Association of State Energy Officials and BW Research Partnership. It provides employment data for the energy, energy efficiency and motor vehicle sectors.

The new reports show the tension between the two goals the Biden administration has pushed as part of a transition to clean energy: fighting climate change and creating a high-paying clean energy workforce.

“There are people who sort of are ‘climate at all costs’ and people who are ‘worker/maintaining existing jobs’ at all costs,” said Phil Jordan, vice president at BW Research Partnership, which conducted the research. “I think that there’s a balance in between and policy needs to really reflect them.”

Jordan pointed to the difficulty of comparing wages across energy technology sectors because of factors like accessibility, skill and education requirements and geographic distribution. Jobs that pay significantly higher than the national median wage are also likely to require more experience, education, training and certifications.

Workers in the nuclear industry received a median hourly wage of $39.19, equivalent to $81,515 a year — more than double the national median, although the industry accounts for less than 1 percent of total energy jobs. Nuclear workers tend to need advanced training and other requirements, boosting their earning power — but they’re up against a string of nuclear plant retirements, with five nuclear reactors scheduled to close this year.

Shutdowns of nuclear plants could also threaten the U.S. effort to fight climate change, Moniz said. “Without the nuclear fleet carrying on, our carbon goals just become all that much more difficult because nuclear remains the single highest zero-carbon electricity source,” he said.

Energy efficiency workers, including those engaged in building efficiency improvements such as weatherization, made up 28.4 percent of total energy employment in 2019, according to the report. But workers in that sector had a median wage of $24.44 an hour — significantly lower than nuclear workers and nearly $6 lower per hour than natural gas workers, who made $30.33. Fast-growing sectors in the renewable energy sector, solar and wind also showed median wages below that of fossil fuel workers: $24.48 for solar and $25.95 for wind.

Oil industry jobs earned a median hourly wage of $26.59, while making up 10 percent of the total energy workforce in 2019. Coal, making up just 2.2 percent of the workforce, had an hourly wage of $28.69.

Moniz suggested that fossil fuel workers will often be able to find new jobs without relocating — echoing current Energy Secretary Jennifer Granholm, who has advocated for “place-based” solutions to the loss of fossil fuel jobs. Granholm has also said Biden’s plan would focus on creating manufacturing jobs to develop supply chains for wind, solar and new battery production in the United States, rather than relying on imports.

“The really important message for fossil fuel workers is that we’re not going to leave anybody behind,” Granholm said on SiriusXM radio last week.

The sheer scope of the Biden administration’s clean energy plans will require creating jobs across multiple industries, including construction, grid modernization and demand-response companies that cut energy costs by shifting power consumption. That creates a potential for a labor shortage, Jordan said.

In fact, an earlier U.S. Energy and Employment Report showed that energy companies were already having trouble filling construction jobs before the pandemic struck, with 83 percent of employers reporting that hiring was somewhat difficult or very difficult. But for now at least, there appears to be some slack in the construction labor market, with last week’s monthly jobs report from the Bureau of Labor Statistics showing employment in overall construction remains 182,000 below its February 2020 level.

Without a concrete pathway forward, the United States’ plans to create millions of new construction jobs could run directly into a lack of workers trained for the energy sector, according to Jordan.

“What is a power line construction company to do?” Jordan said. “If they’ve got to fill 1,000 openings, and everybody who’s sending them resumes or applications were formerly dishwashers, housekeepers or retail sales clerks, they can’t just show up at a job and start laying cable.”