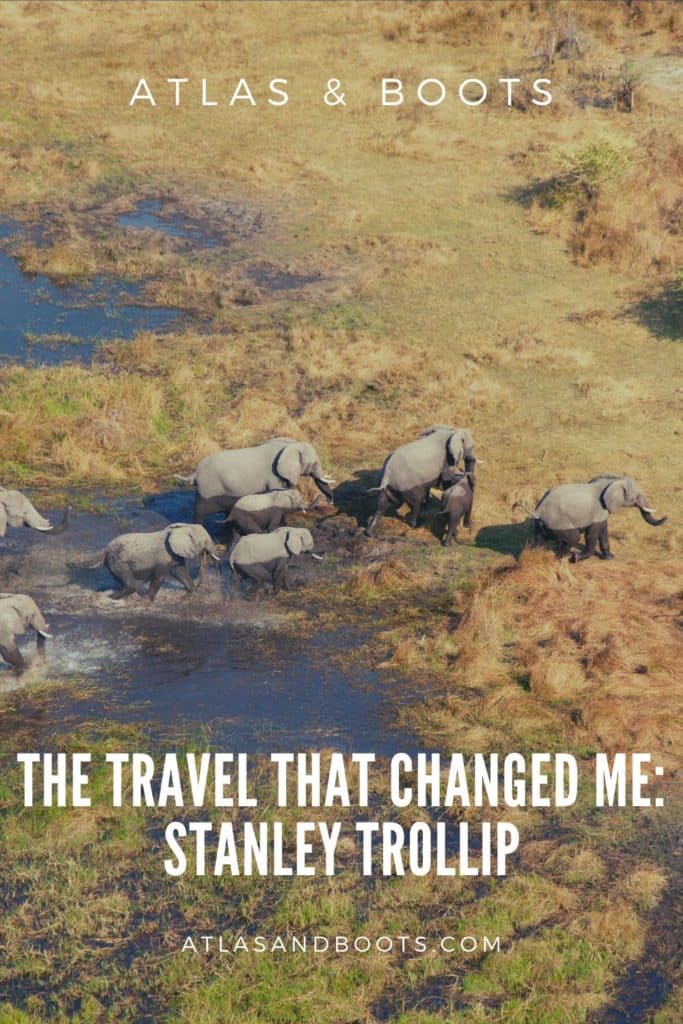

From an unplanned landing in the Namib desert to hyenas attacking wildebeest, author Stanley Trollip tells us about the travel that changed him

It’s fair to say that Stanley Trollip has had an eclectic career. At various points in his life, he has been a professor, a psychologist, a pilot and an author – each a consuming role in its own right. This professional pluralism started early in life; Stanley’s time as an undergraduate took twice as long as usual due to his participation in a range of sports (cricket, rugby and field hockey) as well as his involvement in the anti-apartheid movement.

Born in Johannesburg, Stanley saw first-hand the changes that swept through South Africa – a place, he says, that still feels like home though he has spent more time outside it than he has inside. Today, he splits his time between Cape Town, Minneapolis and Denmark.

In many ways, it’s these multitudes of roles and places that led to Stanley’s first novel, A Carrion Death, which he co-wrote with a friend under the name of Michael Stanley. The novel introduced Detective Kubu and, eight books later, he’s still going strong.

With the latest, A Deadly Covenant, out now, we asked Stanley to tell us about his past lives and travels.

You grew up in South Africa under apartheid. What was that like?

I grew up in a household that opposed the National Party (or Nats, as we called them), which was the political party that formalised apartheid. My parents supported the Progressive Party and its sole representative in Parliament, Helen Suzman. It was the only party to advocate a multi-racial society, albeit with qualified franchise for Blacks. We lived in her constituency, and I cut my political teeth working on her election campaigns.

At university, I was a member of NUSAS, the National Union of South African Students, which was fiercely opposed to all racial discrimination, particularly in education. It was a rough time in South Africa with political and student leaders of all colours suffering home arrest or banning – the latter preventing them from participating in any form of political and often social life. As the editor and photographer of a student newspaper, I had many confrontations with members of the Special Branch, whose roles included infiltrating organisations and intimidating opponents of the government. A very scary time it was; with taps on my parents’ phone, cars parked outside, police showing up at private meetings, and so on.

The country was unbelievably lucky to have a man of the stature of Nelson Mandela as its first president. He was able to bring many disparate factions of all colours and political persuasions together. When he retired, the country was already shaking off the shackles of apartheid, albeit with a number of huge challenges remaining – education, housing, jobs, etc. Each one would have been daunting to an established government, let alone to one with little experience in governance. When Mandela retired, optimism was high.

Unfortunately, I think that the third president, Jacob Zuma, felt that the country owed him something for all the years he had been in exile opposing the apartheid government. He and his friends and ‘business associates’ looted the country of billions of rands. In addition, by lining the pockets of hundreds if not thousands of supporters, he created a network of people who regarded themselves as entitled, but were not only corrupt but also incompetent, exacerbating the existing problems rather than solving them.

Surprisingly, I am optimistic. Despite the chaotic state of the country’s power supply and its railways, the prevalence of its poverty and associated violence, and its extreme unemployment, there are many positives: an independent judiciary, a free press, millions of new homes built replacing the shanties, and young South Africans who want a multi-racial country to succeed and thrive. Creating jobs and getting rid of the old politicians would be two huge steps towards the Rainbow Nation realising its potential.

You split your time between Minneapolis, Denmark and Cape Town. Where’s home?

At the risk of sounding trite, each one is home when I am there. Emotionally, however, I am still a South African even though I’ve lived outside the country far longer than I’ve lived in it. There’s something about those formative years, probably reinforced by the struggles during the apartheid years, that stays with me. The emotion I and many friends felt when Mandela was released and democracy introduced was overwhelming. We all cried – from joy, from relief, and from hope.

You are a professor, a psychologist, a pilot and an author. Which are you first and foremost?

Fortunately, I don’t have to choose. I was a professor, now long retired; I was a psychologist; and I was a pilot, having reluctantly hung up my goggles and helmet a number of years ago. So, now I am only an author, sometimes using the experience from my erstwhile skills.

Tell us about your time as a pilot. Can you recall any funny or unusual moments?

I was awarded my Private Pilot License in South Africa in 1979. A couple of years later, when I was a student at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, I was fortunate to have a research assistantship at the Aviation Research Laboratory, where I flew as a research pilot for a number of studies, including my own PhD dissertation, which explored how computer-based simulations could be used in pilot training.

I have one distinct memory from those times nearly fifty years ago. Winter weather in Urbana Champaign was awful – weeks and weeks of damp cloudy weather. I would love to take a plane above the clouds into the sun to shake the winter blues. I often have a hankering to do that again when in the dark, damp, dreary winters in Denmark.

During the 1980s, I had a professorship in the States, but didn’t enjoy teaching during the summer months. Instead, I would head to South Africa to see family and friends. I also often rented a plane, filled it with friends, and headed off to Botswana and Zimbabwe on safari – bird- and game-watching. Those trips have special memories – of flying low over dirt landing strips to shoo away the elephants or other animals before landing; of surrounding the plane when on the ground with dried thorn bushes to prevent hyenas from chewing the tyres; of landing at little airports to refuel only to find there was no fuel to be had.

On one of those trips, I rented a plane, which had just come off its annual inspection. We had nothing but trouble with it – nothing serious, but lots of little things that weren’t quite right. The most memorable event was flying over the Kalahari, when the door popped open, terrifying my passengers. I knew that we weren’t in any danger of being sucked out but all my navigation charts disappeared into the afternoon air.

One other event sticks out in my memory. I had been hired by the Department of Civil Aviation in Namibia to give a workshop on human factors in aviation. They had no foreign currency to pay me. Instead, they offered me a small plane for 10 days to fly at their expense around the country. My first stop was to be Sossusvlei in the massive Namib-Naukluft National Park desert, home to spectacular sand dunes, some of which are 1,000 feet high. The hotel I’d booked had a dirt strip I could land at. Unfortunately, I couldn’t find it as it was the same colour as the surrounding sand. Eventually, I spotted a farm and landed to ask for directions. When I was told how to get to the hotel, I went to take off only to find the battery in the plane was flat. I felt a wee bit foolish asking the farmer to bring his tractor to help jump-start the plane. It turned out I was only a five-minute flight from my destination.

What’s the best view you’ve seen from the air?

Large herds of elephants, sometimes several hundred strong, in Botswana’s wonderful Chobe National Park moving north to Zimbabwe.

Tell us about the travel that changed you

On one of my flying safaris, we were on the Savuti Plains of the Chobe National Park when we saw a pack of hyenas hunt and kill a wildebeest. Although they are normally scavengers, hyenas can be ferocious hunters when hungry. After a few hours, the wildebeest had disappeared because hyenas eat the bones as well as the flesh.

That evening, over a glass of wine or two, my friend Michael Sears and I decided that if we ever wanted to get rid of a body, we’d leave it out for hyenas. No body, no case!

We thought the whole idea was a great premise for a murder mystery and since we were both avid readers of the genre, we resolved to try to write one.

We were both professors at the time, so with typical academic alacrity it only took about 15 years before we started writing. Eventually, Michael drafted the first chapter in March 2003. Three years later we finished A Carrion Death.

It took some time to find an agent and after numerous rejections, we found one in New York. A month later, she’d sold a two-book contract to HarperCollins. We were gobsmacked.

Before that Savuti trip, I had never thought of writing fiction even though I had penned a number of textbooks with academic friends.

So here I am, nearly 20 years later, with eight Detective Kubu books under my belt, as well as a thriller and numerous short stories, all co-written with Michael. I have also written one thriller by myself.

That safari and those hyenas completely changed where my life was headed. And what a trip it has been.

Do you still have a dream destination you haven’t yet seen?

Other than being at airports, I’ve never been to India. So that’s at the top of my list. I also want to return to my favourite country, which is Egypt, especially to see the new museum in Cairo.

To guidebook or not to guidebook?

When I’m the pilot, I’m well-planned, trying always to be thinking ahead of the plane to be prepared for the unexpected. However, I travel in very much the same way as I write. Michael and I are pantsers. That is, we write by the seat of our pants. Rather than adhering to an outline, we have a vague idea of what our work in progress is about, but let the writing take us where it wants.

Similarly, when I travel, I read an overview of where I’m headed and perhaps note a few places I’d like to visit. However, when I reach the destination, I am moved by who or what I find there. As I’ve aged, I now prefer to have at least my accommodation organised before I arrive.

Finally, what has been your number one travel experience?

Number one place: Egypt. Number one experience: flying safaris in Africa.

Enjoyed this post? pin it for later…

In Stanley Trollip’s latest book, A Deadly Covenant, a contractor unearths the remains of a long-dead Bushman in the Okavango Delta. Rookie Detective David ‘Kubu’ Bengu of Botswana CID and Scottish pathologist, Ian MacGregor, are sent to investigate.

Lead image: Gaston Piccinetti/Shutterstock

[flexi-common-toolbar] [flexi-form class=”flexi_form_style” title=”Submit to Flexi” name=”my_form” ajax=”true”][flexi-form-tag type=”post_title” class=”fl-input” title=”Title” value=”” required=”true”][flexi-form-tag type=”category” title=”Select category”][flexi-form-tag type=”tag” title=”Insert tag”][flexi-form-tag type=”article” class=”fl-textarea” title=”Description” ][flexi-form-tag type=”file” title=”Select file” required=”true”][flexi-form-tag type=”submit” name=”submit” value=”Submit Now”] [/flexi-form]

Tagged: Africa, botswana, interview, South Africa, travel blog, wildlife, Zimbabwe