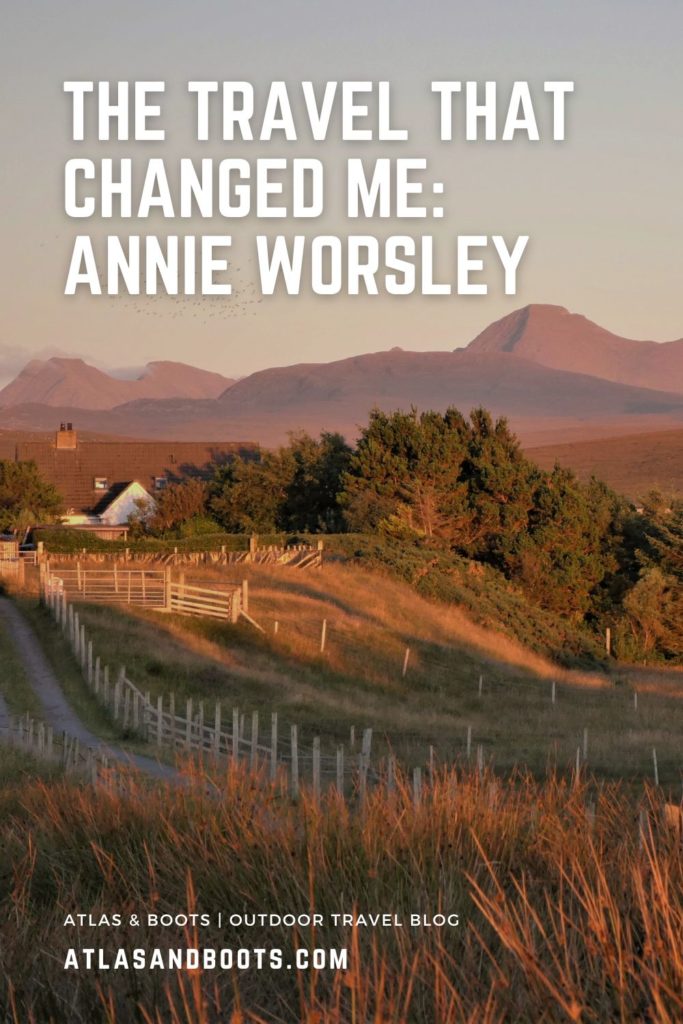

Annie Worsley traded a life in academia for that of a crofter. Here, she tells us about her new life, the art of slow walking and the travel that changed her

It’s fair to say that Annie Worsley has not followed a conventional career path. She began life as a physical geographer focusing on the relationships between people, landscapes and the natural world. Her work took her to the New Guinea Highlands in 1979 where she examined the environmental history of montane rainforests and human impacts on the landscape.

After a career break to raise her children, Annie returned to academia in 1999, this time closer to home. She investigated long-term environmental change in the peat bogs, hills and coasts of northwest England along with the effects of pollution on human health in urban areas.

But, in 2011, she and her husband moved to Scotland to take on Red River Croft, an agricultural smallholding on the western coast of Ross-shire in the northwest Highlands of Scotland. Between working the land, writing essays for journals and blogging, Annie recently penned her first book, Windswept.

Here, she tells us more about the book, her unique way of life and the travels that led her there.

1. You used to work in academia and now you’re a crofter. How did that come about?

For 45 years, I had been coming to the Scottish Highlands, firstly with my husband to climb the hills and explore some of Scotland’s wilder places. We then brought our four children on holidays here, so my love of Scotland has occupied two-thirds of my life.

Returning to academic life – something I didn’t think was possible after so long away having my family – I taught physical geography and environmental science with mountains, peat bogs and coastal landscapes at the heart of student learning. Fieldwork in Scotland and Cumbria were important parts of my courses and, during that time, we continued to holiday up here.

But there comes a point in one’s life where there’s a deep and resonating sense that change is coming. We both felt it. We were years away from retirement. Scotland was calling.

Originally, we didn’t intend to buy a croft but the more we learned about crofting, the more it seemed like the right thing to do. We would need to earn an income somehow and, perhaps recklessly, we had no firm plans. Then my husband got a job as a local pharmacist and I began to write, and our crofting life began to take shape.

2. How did your friends and family react?

By the time we moved here, our children had left university and were employed. They wholeheartedly supported our plans to move north. After all, they had lots of holiday memories of high summits, empty beaches and quiet trails. And for them ‘home’ would be somewhere they loved and understood.

Our extended family were more surprised. They wondered why we had both given up well-paid jobs, careers, pension prospects and security for an unknown future. But when they came to visit, they understood our love of this place and eventually came to ‘see’ the magnificent beauty of the Highland landscapes through our eyes. My colleagues and friends were puzzled. Some thought we would not last long, others knew how much I loved Scotland and wished us luck.

I began to write my blog and post photographs for family and friends, especially those who had never visited the Highlands, so they could see and read about our new home.

And then, one by one, the children were married and began to have children of their own. Now the reaction of all our family is how soon can we get to Gran and Grandpa, how soon can we go to the beach or walk in the hills and forests, swim in the sea or splash in the river.

3. What does a typical day for a crofter look like?

Traditional crofting has changed here in Wester Ross. Where once crofters had fields given over to food production or crops such as hay, barley and oats, when their sheep and cattle roamed on the ‘common grazings’, many now harvest meadows for silage and animal numbers are considerably reduced.

We manage our croft for wildlife conservation and traditional hay. On a typical day I walk the 10 acres to check fences, record wildlife and wild plant species, and spend a fair bit of time inspecting the various nooks and crannies for clues to what animals have passed through the croft – whether the local otters have left spraint, for example – and watch the birds passing back and forth between the meadows, our small patch of woodland, the surrounding hills and coast.

I will take photographs and make notes about what I see or hear and, eventually, some of these images and words will make their way into my writing. When the hay is cut, the community come to help. Young crofters from the nearby ‘township’ bring their old tractor and cutter and begin the slow process of cutting, tedding and drying hay in windrows.

Many crofters here in Wester Ross supplement their income with other jobs besides managing their land and animals, so much of their crofting work is undertaken in the early hours of the day or evenings. We are no different. When my husband has finished work in the pharmacy and I have finished writing, we will set to work.

4. Windswept explores life and nature in the Highlands. What’s the message you hope readers will take from the book?

I think the most important message is one of interconnectedness. Crofting taught me much more about mutualism; about how we help each other. Once our hay has been harvested, it is shared between the young crofters who keep livestock and I love the notion of such symbiotic relationships with others.

And we are not only connected to our crofting neighbours but to our non-human, wilder ones too. Recognising the small, intimate connections with nature came from learning about our local environment. Deep learning through physical, elemental experiences of nature, wildlife, weather and landscapes is how I tried to teach my students but I have learned more than I ever taught by coming to understand and love this place and all its inhabitants, its moods and changing colours.

That knowledge was gained by taking time to notice the smaller lives that form part of our croft. If it is possible to spend just an hour or two slowly moving through a landscape and noticing the life around us, then the interconnections become apparent. The importance, power, beauty and ability of nature to restore us and support us is also visible. I learned this practice of slow walking and noticing firstly from my mother and, later, from the people of New Guinea, the world’s second-largest island.

5. What’s the most surprising thing you learned during your research?

The most surprising thing I learned is that even small changes in one small part of the croft could have remarkable impacts on biodiversity. Collecting data (plant species numbers, plant height, insect and bird numbers) over the last decade has produced clear evidence of a rather remarkable transformation.

We hear a lot about large-scale rewilding projects and that is wonderful, but even on just a few acres, preventing grazing on one place and allowing it in another, or restricting animal access to the riverbank completely altered the vegetation dynamics. The knock-on effects include increasing wildlife numbers. I knew it would happen but I was surprised by the speed of change.

6. Let’s move on to the travel that changed you. What region or trip has impacted you most?

The most important, significant and wondrous trip of my life was undertaking doctoral research in the Highlands of Papua New Guinea in 1979. The Highlands had only begun to be explored following World War Two and during my research there I was able to visit and stay with indigenous communities who had had little or no contact with westerners.

The high montane forests were incredible. The landscape was extreme – deeply incised valleys thick with jungle and high volcanic summits. I learned about the plants and animals and how the communities lived, how they hunted, harvested plants and grew food in small forest clearings, made clothing from materials they gathered, about plants used for medicines, and about their beliefs and traditions. The whole experience was utterly life-changing. It influenced how I raised my own children, what I taught my students and, later, the direction of my academic research.

7. Do you still have a dream destination you would like to visit?

I would love to visit Africa. My great-great uncle was known as Trader Horn. I grew up on tales of his adventures. I would like to retrace his steps through South and Central Africa.

8. To guidebook or not to guidebook?

If I am visiting a city for the first time I would definitely ‘guidebook’. I love guidebooks. I love reading about the history of a place, its roots and foundations and changing stories, and good guidebooks offer insights that a month of city walking might not find. But, when exploring a rural area, then no, I prefer to slowly wander the trails and talk to people.

I am a great believer in ‘stop and chat’, which in the past has annoyed my kids. but I love gathering stories from people as well as collecting data about places through science – that’s what we geographers do!

9. Hotel, hostel or campsite?

That is a hard question. Now I am an elder, a grandmother, I am much stiffer and slower than I used to be, so I would probably look for a small hotel, one tucked away in the back streets of a city, or perhaps one in a small rural village or town.

As a youngster, I used to love staying in bothies and after my time in New Guinea, I would have been happy to lie down and sleep anywhere. Even now, whether I stay in built accommodation or not, anywhere away from the crowds is my preference.

10. Finally, what has been your number one travel experience?

It has to be my trip to New Guinea. In the late 1970s, the journey was taken in a series of flights from London to Dubai to Sri Lanka to Hong Kong, then a longer flight to Brisbane followed by a short hop to Port Moresby, the capital of Papua New Guinea. From there, a tiny plane flew into Mount Hagen in the Central Highlands.

Once there, I travelled a short distance by jeep to the Kuk Swamp to work with scientists from the Australian National University in Canberra until I was finally left on my own to travel on foot and stay with indigenous communities in Enga Province.

Annie Worsley’s Windswept: Life, Nature and Deep Time in the Scottish Highlands is a fascinating blend of history book and almanac, exploring the epic story of Scotland’s landscape and how Annie carves a life out there.

Enjoyed this post? pin it for later…