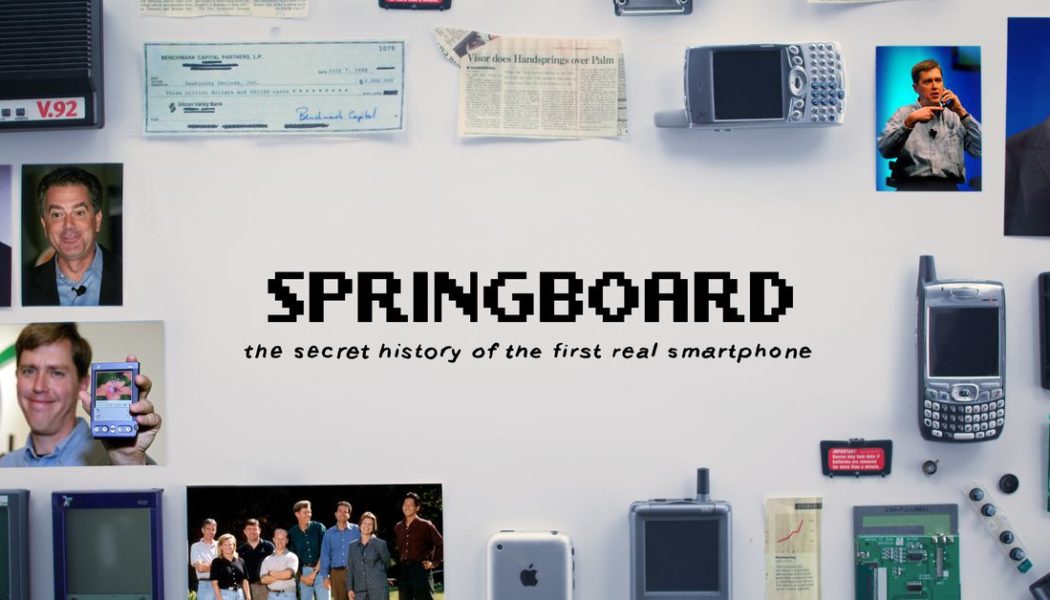

You may have read on the site that Verge executive editor Dieter Bohn has been working on a documentary called Springboard: the secret history of the first real smartphone. It’s about a company called Handspring working on, you guessed it, a very early smartphone. It’s a story that I think will resonate with the Decoder audience, so I wanted to sit down with Dieter and talk about it. He even brought an exclusive clip that didn’t make it into the film.

That documentary is streaming now on The Verge’s new streaming apps that you can get on your TV or set-top box. We have them for Android, Amazon Fire TV, Roku, and Apple TV. We’ve been working on these for a long time. It’s a little more complicated than you might think to make these apps, make them good, and distribute them on everyone’s app stores. We learned a lot about usage rights and rival closed caption formats — we ran into some real Decoder pain points.

But apps are cool, and you can watch your videos in 4K. You can also listen to this very podcast on our fancy streaming apps on your TV with glorious surround sound. And we’re going to start doing some exclusive videos on the platform, including the one I mentioned up top: a documentary that Dieter and our video team made over many months called Springboard.

This transcript has been lightly edited for clarity.

Dieter Bohn, you’re the executive editor at The Verge; tell me about Springboard.

Springboard is the story of a company called Handspring. This was one of the very early companies to try and make one of the very first smartphones. It had a storied legacy, it had genius founders, and it had a nonstop stream of corporate catastrophes that prevented it from being successful. The long and the short is the story of innovation and a scrappy startup trying to do something incredibly ambitious, but there were many reasons why it was not destined to succeed.

We call it a scrappy startup, and it mostly was a scrappy startup, but at one point, it was one of the most successful and fastest-growing tech companies in America and American business history.

That’s right. So the CEO was Donna Dubinsky, and they had launched the Palm Pilot, which you have probably heard of. And through a series of corporate acquisitions, they ended up being stuck at a modem company called 3Com. So they spun out and started Handspring and convinced 3Com to license Palm OS to them. And they launched the Visor, a PDA, and it was wildly successful, relative to other PDAs on the market. So they had a huge, huge initial rush of interest and sales, and things were rocking and rolling pretty fast for them.

They were early to the idea of a smartphone, and the thing they wanted to make was a smartphone. They had some major challenges on the technical side of building a smartphone that early. It seems like their bigger challenges were just finding a market, finding the right people who could sell this thing to other people.

The really interesting thing about the technical challenge, in particular, is the parts didn’t exist. They wanted to make a smartphone that had a radio that could handle data, and they just couldn’t buy it. It did not exist. The entire infrastructure of factories and supply chains that now exist in Shenzhen and Vietnam and wherever didn’t. So they ended up finding one company, I believe it might have been in France, that happened to make the radios that they needed. And they just had to cobble stuff together.

They also had to make bets on what actual radio networks would exist because there were all sorts of weird pager networks and other data networks. So they got through those problems, but then the question becomes, “How do we sell this thing?” And selling phones direct to consumer was not a real viable business. Everything went through the carriers. Before the iPhone, the carriers had absolute control over phones, not just which phones they decided to sell or not sell, but how they worked and what they were allowed to do from a capability perspective.

This is the thing I end up talking about on Decoder a lot: the best products don’t always win, and there are often gatekeepers, visible or invisible, that are actually shaping the market. Even though they had the best phone in this very early category, they were gatekept out of the market in various ways, but it was still popular. People were still covering it. John Fort, who has been on Decoder, he’s now an anchor at CNBC, he was a cub reporter at the San Jose Mercury News at the time, and Springboard is full of clips of his byline as a newspaper reporter. There was a lot of attention being paid to this company. Why were they not able to overcome those gatekeepers?

A lot of it was those gatekeepers were more powerful than they were. Maybe not today, but there was a period after the iPhone where you could get something out to the market without having too much carrier interference. And Handspring did not live in that world whatsoever. They had a hard time getting the phone to sell in some European markets because it didn’t have a 10-key keyboard. The carriers didn’t believe that QWERTY keyboards would be popular and sell. Sprint did not believe that anybody would want to send a picture on their phone. They didn’t want that to happen because other phones couldn’t do it.

But Handspring also faced a bunch of external problems. They made a huge deal to get a huge office building right after the market crashed. And that market crash caused all sorts of other problems for them, including an excess inventory problem from Palm, which ended up forcing the prices down on all PDAs. So their cash cow that was funding the launch of this phone went away. They were also constantly in the precipice of running out of cash, running out of resources. And they were on that precipice while everybody around them was actively fighting the success of this thing.

The ideas that happened at Handspring, that company was reacquired by Palm, and then Palm did a bunch of stuff, those ideas are sort of everywhere in computing now. Where are the people? The people had long careers after the Handspring collapse?

A few of the key characters, Jeff Hawkins and Donna Dubinsky, went off to do the thing that Jeff always wanted to do in the first place. For Jeff, smartphones and PDAs was always a side hustle. His real interest is in brain research and trying to figure out how neuroscience and the brain works. And he has some unique theories on that. He finally went off and founded this company called Numenta, and a bunch of the Handspring people came along with him because they all really enjoyed working together. So they’re still over there doing that. Other players went to other places.

One thing that’s interesting, this isn’t quite a Handspring thing, but you can follow some of the software history from Palm over to this other company, Palm Source, all the way to some of the founding team for Android. So it wasn’t just the Sidekick team that came over [to Android]; it was also a bunch of expats from Palm Source that originally were trying to bring Palm OS into the future that ended up writing some of the foundations for Android.

Just to be clear, the Android project at Google was an acquisition. If you remember the T-Mobile Sidekick, which was a phenomenon for a hot minute, the team that made the Sidekick founded a company called Android. Google bought that company, and they brought over a bunch of ex-Palm people as well.

Yeah.

And that was the beginning of Android. That theme of “you have ideas, you get them wrong, you keep working at them, ultimately some combination of wireless carriers crushes you out of existence” is a pattern that repeats over and over again. But you can see the lineage is right there, and some of the core ideas of how you would operate a phone that connected to a network and was also a computer started at Palm in a very real way.

One of the people we interviewed is Rob Haitani, who was the interface designer for Palm OS and later at Handspring. He was trying to convince these software engineers, “This is how you make mobile software.” In the ’90s, no one knew how to make a mobile app. So he would have to be really rigorous about, “No, no, fewer tabs and big buttons. And it needs to be understandable. It has to fit in 160 by 160 pixels.” By the way, this was the screen resolution on these devices.

He got so tired of explaining how mobile worked to people, so he finally wrote a book that was based on the ideas that got attributed to him. It was called the Zen of Palm, and he had all these cones. So an example was how do you fit a mountain into a teacup? And software engineers would say, “I don’t know, you something, something, something.” “No, you don’t. You just find the diamond. That’s the one that goes in the teacup. That’s the only thing you care about. That’s what goes in your mobile app. Everything else can get buried in a menu.”

I’m very confident lots of product managers listen to the show, I hear from you. We live in a world where a lot of this stuff is organized through our systems or competing philosophies of product design and product management. At that point in time, they were just very nascent. It was the beginning of thinking about how to architect computing systems and interfaces, and [Palm and Handspring] invented a lot of this stuff.

There were competing visions, to be clear. I mean, Pocket PC was a thing, WIN CE, I guess technically we’re talking about, which was a very Windows-esque interface. It had a start button, a literal tiny start button in the lower left-hand corner. And of course, Apple famously made the Newton, and that didn’t go so hot because it was also a little bit overloaded. There was General Magic — everyone has probably heard of that story as well. That was also overloaded.

One of the things that Palm figured out was you need to make the simplest possible app that can do the stuff that you want and don’t do more than that. They had an aggressive willingness to say “no,” and they were one of the first tech companies making consumer products who really evangelized the idea that you say “no” before you say “yes.” That hones your product to achieving the things that you want it to do and allows it to do those specific things very well. And then, you can start growing and making it into a more general-purpose platform.

So you mentioned Apple, and that idea about saying no is sort of indelibly associated with Apple and Steve jobs now. There is some connectivity between Apple and the Palm story.

Donna Dubinsky used to work for Steve Jobs. Ed Colligan, who ran marketing and later on became CEO of Palm, also worked for Apple for a time. So they had relationships with Steve Jobs. More than once, there would be a phone call where it’s like, “Is this phone call about Apple maybe buying Palm or Handspring?” Maybe it is, maybe it’s not. And the pivot point of the Springboard documentary is this meeting where Jeff, Donna, and Ed went to speak to Steve Jobs about getting the Mac to support their Visor PDA. Steve Jobs didn’t believe in the PDA. He didn’t believe in their vision. And Steve Jobs tried to present his idea of the digital hub.

If you remember, he had the Mac at the center of it, and he thought everything was going to circle around the Mac. And Jeff Hawkins said, “No, Steve, I think you’re wrong.” And right next to Steve’s chart on the whiteboard, he drew his own chart with a phone at the center of it. This was well before Apple had been talking about the iPhone at all. And it may be that this was one of the things that convinced Apple, and Steve Jobs in particular, to get serious about coming back to the idea of mobile after walking away from the Newton because that had been such a mess.

Famously Ed Colligan, who was running Palm, said, “The PC guys are not just going to walk in and figure this out.” It’s quoted everywhere, and I know that you tried to actually get this audio, unsuccessfully.

At the time that Apple was introducing the iPhone and other big companies were introducing their phones. You talked to him about that quote.

Yes, I did.

It turns out at least one PC company figured it out. The other ones did not, but you talked to him about that quote. This is a little extra, it’s not in the documentary, but it’s just so fascinating to me. What did he say when you asked him about that quote?

You’re right, it didn’t make it into the documentary because explaining the context around the quote was too complicated. He said it ahead of the iPhone announcement, but everyone knew the iPhone was coming. It was at a Churchill Club breakfast, and his contention is that he was speaking about the PC industry in general and that making phones was very hard. He knew just as well as anybody because they had been trying to make a smartphone before supply chains for any of these parts even existed. And he also understood, based on his history with Palm, that people had been trying to shrink PC interfaces into tiny mobile interfaces for a while. And that was the wrong idea.

So his contention is that he wasn’t speaking specifically about just Apple. He was talking in general about PC people coming in and trying to make phones. So here’s what he said about his famous quote when I interviewed him:

Ed Colligan: It’s pretty silly, because if people actually go back and look at that interview, they’ll see that it was probably an hour long. And I thought it was really great, which is one of the sad things about it, that this one thing came out of it.

But you know, what I meant by that [quote] I think was taken out of context. First of all, I’ve been an Apple proponent for my entire life. My entire career has been built on Apple products. My first company was an accessory company for Apple. My second company was an accessory company for Apple. Radius was an accessory company for Apple. So I’m a huge Apple guy and I always have been, so I wouldn’t disparage them. So when I use [the phrase] PC guys, if I was using that term, it probably was about HP, Compact, Dell, and whoever.

But even if Apple is included in that grouping, what I meant was that these are hard devices to create. And to really nail it, especially the radio side, it’s going to take some real effort. I didn’t say it was impossible. I just said it’s not going to be super simple. And in fact, if people look back at the original iPhone, it was actually a pretty horrible phone, day one. And it did take some iteration for it to get right. Now they had enough other compelling elements around it that people overlooked that, to a large sense.

So they did really well. And I never, in my wildest dreams, would say Apple can’t create a product in this space. I would’ve never said that and I would’ve never felt that, but I probably just was saying, “Hey, this is a hard business.”

You can judge whether or not he was right about that, but I think that, in general, the PC company that figured it out was Apple, and a bunch of the others kind of didn’t.

A bunch of them didn’t. Most of them didn’t. Microsoft didn’t. And that, to me, is the overall lesson here: you can have the idea early, you can even try to copy the idea, but actually executing the idea is extremely difficult. And one of the themes of Springboard that is very resonant to me is that these things are very fragile, especially when they’re early. And the success actually might not be market success.

The subtitle for Springboard is the secret history of the first real smartphone. We’re aware that Sidekick exists. We’re aware that Symbian was around. But Handspring had the vision for the way that phones should work today, and it was the clearest vision at the time, but that was not enough. You need to understand what the forces are that will prevent your vision from happening. And some of those forces are more than just “can you get the parts?” “Can you build a good product?” Some of it’s stuff like the carriers, stuff like “does the supply chain exist?” And so on. We talk about product fit. That’s a shorthand for a much bigger conversation of what could prevent your good idea from becoming a reality.

This feels like a good place to stop and tell people to go watch this documentary, which is excellent. We premiered it at The Verge’s 10th-anniversary event to rapturous applause in the room — which was pretty cool. You can go visit theverge.com/springboard. It has the trailer; it has the information about all the apps.

I will just remind everyone again, we have new Verge streaming TV apps on Android, Amazon Fire TV, Roku, and Apple TV. Just go into the search box, type in “The Verge,” download the app, watch Springboard.

Dieter, congratulations. It’s a great documentary.

Hey, thanks. Talk to you soon.