With today’s announcement of a new 13-inch MacBook Pro, Apple has finally stopped trying to fix one of the most controversial and problematic hardware designs in its history: the butterfly switch mechanism on its laptop keyboards. After five years of applying bandages to the butterfly keyboard, Apple has switched over its entire laptop line to the scissor-switch-based Magic Keyboard in the span of six months.

Switching the entire product lineup over to a new keyboard in the span of six months is impressive, but the decision to finally do so came far too late. Apple obstinately stuck with this keyboard design for much too long, hurting its image and causing wholly unnecessary hassle and cost for its customers.

I would say good riddance, but I am typing this on a MacBook Pro with a butterfly keyboard right now. If you’re using a MacBook yourself, there’s a good chance you’re typing on one, too. So while the butterfly keyboard may be gone from Apple’s store, it’s certainly not gone from this world.

The era of the butterfly keyboard kicked off with 2015’s 12-inch MacBook. It was just called MacBook (no “Air” or “Pro” modifier), and it was heralded as a new kind of laptop for Apple. It kicked off a new design language, complete with USB-C ports and that butterfly keyboard. For a brief time, it seemed as though Apple intended it to be the MacBook, but it was too small, underpowered, and expensive to go truly mainstream.

That MacBook was discontinued in July 2019, replaced by the refreshed MacBook Air. But that little MacBook really was influential: the keyboard mechanism spread to the MacBook Pro and the first iterations of the redesigned MacBook Air. Apple clearly believed in it and thought its benefits outweighed its problems up until relatively recently.

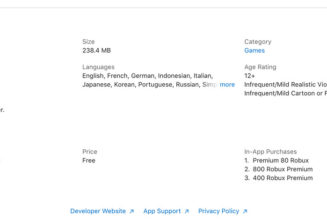

The primary benefit of the butterfly keyboard was that it was thin, giving Apple more flexibility to use the extra space for more components or to make the entire laptop thinner. It also meant that the keys were more “stable” as you pressed down, giving you virtually the same feel when you pushed down on the corner of a keycap as the center. Notably, today’s new 13-inch MacBook Pro is ever so slightly heavier and thicker than the last one.

But those benefits were eclipsed by the butterfly keyboard’s many faults. The biggest is simply that the design was unreliable. The mechanism was so fragile that seemingly any little piece of debris or grit could break a key, keeping it from working or making it type double letters. Adding insult to injury, Apple’s laptop construction meant that replacing that single key wasn’t a simple operation. It required taking the laptop into an Apple repair center where the entire machine would have to be disassembled.

Casey Johnston was the first major tech journalist to call Apple out on this issue in a serious and sustained way, beginning with a 2017 article in The Outline titled “The new MacBook keyboard is ruining my life.” A March 2019 editorial from Joanna Stern at The Wall Street Journal also made a huge splash, taking the idea that these keyboards are fundamentally flawed to the mainstream.

Through it all and up until the November 2019 launch of a “new” keyboard design in the 16-inch MacBook Pro, Apple kept defending and tweaking the butterfly keyboard. It created a “second-generation” version in 2016. Then, in 2018, it added a silicone membrane underneath the keys to keep dust out (though Apple claimed it was meant to make the keyboards quieter). A third — and, depending on how you’re counting, fourth — generation design followed, with Apple descriptions of its tweaks getting more and more arcane until the last generation when it would only say that there were “new materials” in 2019’s MacBooks.

However, Apple did acknowledge keyboard problems, but it was in a way that implied the problem wasn’t as widespread as people thought. In 2018, it instituted an “extended keyboard service program,” essentially warrantying butterfly keyboards for four years. When it released new MacBooks after that, it even went so far as to say the extended service program would apply to those brand-new machines as they were announced.

Only Apple truly knows how widespread the problems with this keyboard really are, and only Apple truly knows whether those problems made a significant impact on MacBook sales. If they have, it’s difficult to separate that effect out from larger trends in laptop and Mac revenue, which has been little better than flat over the past five years.

Apple’s Mac revenue is Apple’s problem, not yours. If you are a MacBook user, the biggest effect on you is whether your keyboard lets you type. That’s doubly important now, with Apple’s stores shut down in most countries during the pandemic and no clear way of knowing when you might be able to get a repair done.

More than anything else, though, the whole butterfly keyboard saga has been a huge reputation hit for Apple.

For those who thought Apple was sacrificing functionality for thinness across its entire product lineup, the butterfly keyboard looked like confirmation. For those who felt Apple was intentionally making its devices harder to repair as a way to further lock them down and also cut out third-party repair shops, it was another data point. For those who felt Apple had stopped paying attention to the Mac, here was a prime example of a problem allowed to languish to years. For those who felt Apple is still trying to create a “reality distortion field” where everything it makes is great but the truth is much more mundane, well… you get the picture.

The butterfly keyboard hurt Apple’s reputation precisely because the outlines of its problems and Apple’s response to them lined up with some of the biggest complaints people have about the company.

Earlier, I called Apple’s attempts to save the butterfly keyboard obstinate, but a less charitable way of putting it is simply to call it hubris. For some, it called Apple’s judgment into question. How could the company fail to see — or refuse to admit — that it was shipping a bad product?

The Mac has serious challenges in front of it. As Intel’s processor roadmap meanders, Apple is reportedly working on a switch to its own ARM-based processors. As the iPad Pro gains more traditional computer functionality, more people are considering it a laptop replacement. Through it all, macOS has seen slower development compared to iOS, plus less clear direction over the past few years. Are Catalyst apps the future? Is it SwiftUI? How will the impending ARM switchover affect the future Mac apps?

Those are fundamental software questions for the Mac, and answering them could be an invigorating challenge — one that could spark an exciting next era for the Mac. What a relief that we don’t need to worry about fundamental hardware problems at the same time.