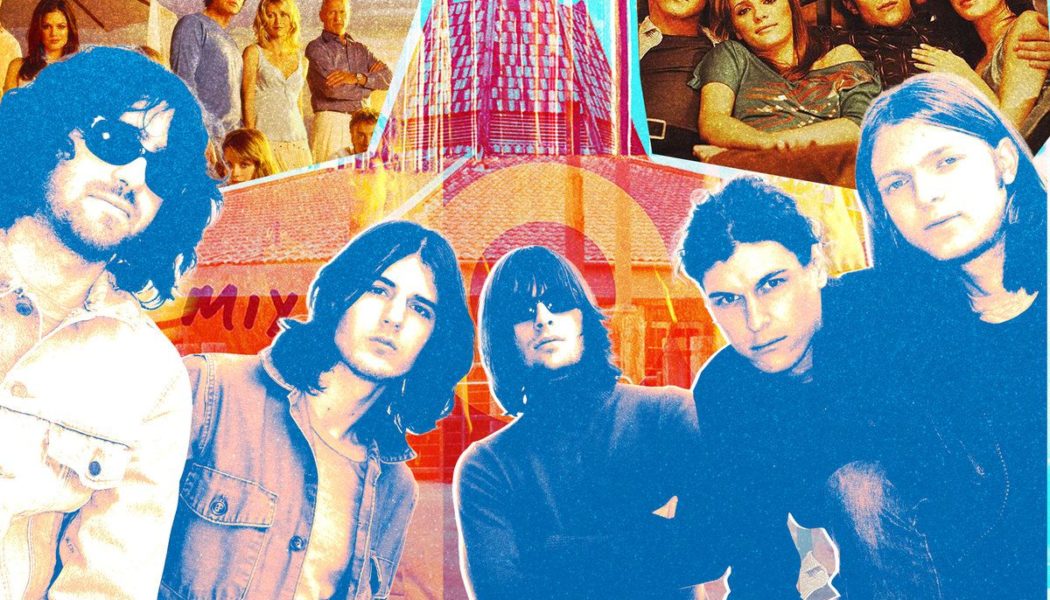

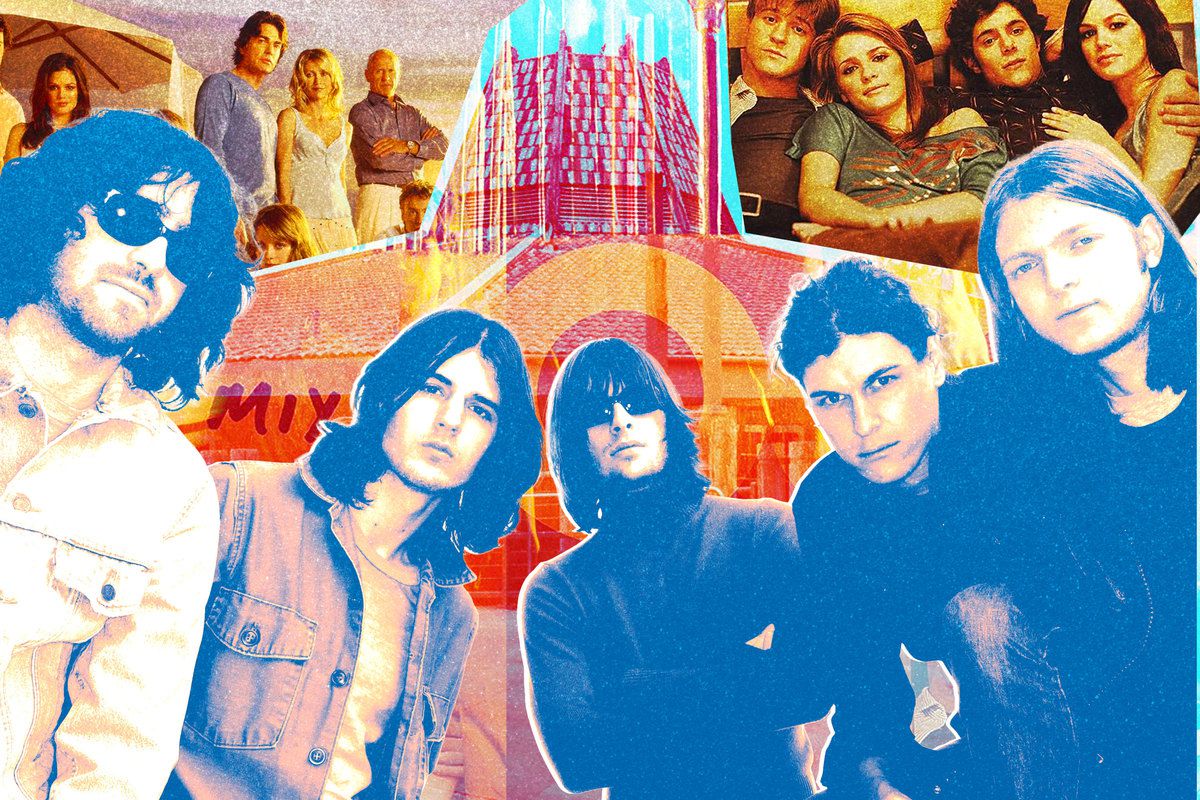

Twenty years since Fox’s seminal mid-aughts teen soap opera debuted, the music is its most enduring legacy

There’s an old cliché in musical theater that when you’re too emotional to talk, you sing. A proposed corollary for the peak aughts teen soap opera might be: When you’re too emotional to talk—because you just shot your boyfriend’s brother, or you hooked up with your daughter’s ex-boyfriend, or you found out that your girlfriend is your grandfather’s long-lost love child, or you’ve been suddenly reunited with your fugitive college girlfriend who burned down a nuclear laboratory and then faked her own death, or maybe that porn you filmed in the ’80s played at your magazine launch party—you play Death Cab for Cutie.

If you are of a certain age and cultural inclination, the sounds of the post-punk indie revival likely became a greater part of your life starting 20 years ago this week, when The O.C. premiered on Fox. The seminal teen drama introduced us to the Cohen and Cooper families of wealthy Newport Beach and to troubled teen Ryan Atwood, who was plucked out of juvie in Chino and dropped in the middle of Kirsten Cohen’s aggressively taupe kitchen. On its face, The O.C. was a typical fish-out-of-water melodrama, but the show was on the leading edge of culture in a few ways—nerd culture as mainstream, in-jokes as the lingua franca of a new online TV commentariat, the bagel guillotine—but none more so than its soundtrack.

Exactly three things are perfect about The O.C., and they are (1) Seth and Summer, (2) Peter Gallagher’s eyebrows, and (3) the music, which over four seasons and six official mixtapes became such a huge part of the show that creator Josh Schwartz considered the music to be its own character. The official soundtrack was an early 2000s alternative paradise, somehow both gloriously earnest enough for Jem’s cover of “Maybe I’m Amazed” to serve as Julie Cooper and Caleb Nichol’s wedding song and cool enough for Beck to premiere five tracks while Seth, Summer, Ryan, and Marissa got stuck at the mall. The O.C. has a strong claim to the most iconic theme song of this century—“California” by Phantom Planet—and it helped popularize bands like Death Cab and the Killers, nudging them from indie into the mainstream. The use of “Hide and Seek” by Imogen Heap at the end of Season 2 spawned its own SNL skit. There are plenty of odes to the O.C. soundtrack out there on the internet; I offer this one because two decades later, I can’t shake this montage set to Spoon’s “The Way We Get By” that opens Season 1, Episode 5, and that’s just part of the testament to the way this soundtrack cemented the show’s cultural moment and its enduring legacy.

For its first seven episodes, Schwartz, with the help of cocreator and fellow music fan Stephanie Savage, built the O.C. soundtrack by digging through his iPod. “California” was both a personal favorite and the right track to reflect the show’s West Coast exceptionalism. Episode 7 ended on a musically high (if emotionally low) note: with Mazzy Star’s “Into Dust” playing as Ryan lifted Marissa’s limp, overdosed body off the alley pavement in Tijuana—sorry, “TJ”—before the show broke for a 43-day-long midseason hiatus.

A few things were happening when viewers were left with that epic cliff-hanger. Fox wanted more episodes of the summer smash hit, pushing the first-season order to 27 hour-long episodes. Second, it was clear the music Schwartz and Savage had used in those first seven episodes was resonating with viewers, and that encouraged the producers to lean even further into bringing songs and bands into the world of the show. Complicating that plan was a third thing, which was that Schwartz was running low on song ideas. So that was when he made one of the best decisions in the history of televised song: He called Alexandra Patsavas, an up-and-coming music supervisor in Hollywood, for help in finding music that might evoke the feel of Southern California or of being in high school, or that would be the perfect fit for a specific O.C. character.

If you don’t know Patsavas’s name, you have likely heard her work through The O.C. or elsewhere. She is, for instance, the reason your Pavlovian response to hearing Snow Patrol may be to assume that somewhere, a handsome TV doctor is dying. She’s the reason you might be considering that orchestral arrangement of Taylor Swift’s “Wildest Dreams” from Bridgerton for your wedding ceremony. (Do it.) In my case, she is the reason I had a big Muse phase in ninth grade after I saw the first Twilight movie.

Patsavas grew up in Chicago, fell in love with the soundtracks to John Hughes movies, and then started booking venues in college, when she brought Jane’s Addiction and Smashing Pumpkins to the University of Illinois. She moved to Los Angeles after graduation to start in the music industry, first working in an agency mail room and then at the licensing firm BMI, where she learned about the role of a music supervisor. In 1995, she landed her first music supervisor role for the Roger Corman B movie Caged Heat 3000. Three years later, she started her own label, Chop Shop Music Supervision, out of her apartment. By the time Schwartz called in 2003, Patsavas had a reputation for great musical taste and a unique ability to use soundtracks to bring out emotion in shows like Roswell (a 1999 WB drama in which high schoolers discover aliens living in their small town).

Together, Schwartz and Patsavas began a process of exchanging mixtapes, crafting The O.C.’s specific texture of West Coast rock, emerging electronic music, and sincere emo balladry. Reminiscing in a recent conversation, Patsavas laughed about the analog nature of their process.

“That was how we started a lot of conversations,” she said. “A lot of music going back and forth, and 20 years ago there was no way to deliver it digitally. I’d be faxing requests to get songs cleared, and I had what I thought was a really sophisticated method of burning a CD one at a time and finally graduating to a 10-pack of CD burners.”

The music that defined the O.C. soundtrack was in part a function of Patsavas’s and Schwartz’s taste and what they thought was right for the show, but it was also music they could get. One of the reasons Patsavas liked to use so much alt-rock for The O.C. was that the healthiest ecosystem for that type of music existed around colleges and college rock stations, which made the soundtrack feel appropriately youthful. At the same time, those bands were often yearning to break through to mainstream radio formats that mostly ignored them. The O.C. premiered at a time of peak radio station consolidation, six years after Congress passed the 1996 Telecommunications Act, which significantly deregulated broadcasting. Before the law passed, a single radio corporation could own no more than 40 stations, with no more than two in a single market. The law increased the market cap to eight and removed the national cap altogether, and by 2001 Clear Channel had grown from 40 stations nationwide to 1,240, with homogenized playlists that played the same songs in heavy rotation.

For an indie band like Rooney, which had hooks galore but didn’t quite fit any of the day’s dominant musical modes, landing a song on an episode of The O.C. was a creative way to be heard. Still, as tempting as a national TV platform was, there were also bands wary of sacrificing indie cred. Patsavas told me she often had to do some convincing around those concerns. Some bands, like Arcade Fire, never agreed to be on the soundtrack, and Rooney frontman Robert Schwartzman told me that even though his band would become the first to perform on an episode of The O.C., they had some initial reservations about signing on to a middlebrow TV project.

“Would that be cool? Is it rock ’n’ roll? Like, is it too mainstream?” Schwartzman said. “There was all that, those thoughts in my mind, and I think in the beginning, we didn’t fully embrace the offer of doing it.”

What sold Schwartzman and his bandmates was how thoughtfully Schwartz had written them into the plot. In Episode 13 of the first season, which aired in January 2004, new character Oliver Trask gets Marissa and her friends tickets to the Rooney show, which serves as the backdrop for several important plot points: Seth and Anna reveal to Summer that they’re a couple, and Ryan catches Oliver trying to buy drugs from an undercover cop. (Oliver is later bailed out by fluffy-brow king Sandy Cohen). But the best part of the episode is the completion of former show villain Luke’s whiplash redemption arc; Luke initially scoffs at an indie band he’d never heard of before realizing that he really, really loves Rooney. Soon we were all chanting “Rooney! Rooney!” along with him: After the episode aired, the band saw a 200 percent increase in album sales.

“It wasn’t like, ‘Oh my God, a movie or a TV show got someone into a song or a band, that’s not something we’ve [ever] seen before,’” Schwartzman told me. “I just think it was cool that a show leaned in so heavily to music, to a West Coast sound, embraced these up-and-coming indie artists and gave them, like, a platform to be discovered in a more mainstream way. That was exciting, you know, to be kind of put into the fabric of the show that he was building.”

Licensing music for TV wasn’t new, but The O.C.’s commitment to weaving music into the fabric of the show came at the perfect time. By the late ’90s, it wasn’t uncommon for bands to seek out alternative paths to get their music heard, as when Moby licensed the music from his album Play for use in commercials and then saw the album reach no. 1 on the Billboard charts in more than a dozen countries. Fox’s American Idol, which debuted in 2002, was also training audiences that they could find music on TV. Of course, the more popular The O.C., and its soundtrack, became during its four-year run, the more bands wanted to have their music featured on the show.

“The music business really found value in that moment,” Patsavas said. “And because of that, we had the opportunity to debut a Coldplay song, ‘Fix You,’ right? We had unbelievable opportunities to showcase brand-new music by essential artists and artists that we loved.”

In Season 2 The O.C. leaned hard into live performances as part of the show’s plot. The success of the Rooney episode encouraged Schwartz to create the “Bait Shop,” a local concert venue made to resemble L.A. clubs like the Troubadour, only seaside. The development of Seth’s character as an indie music nerd helped further write music into the plot.

Originally, though, it was Marissa who was the music superfan, and she was responsible for beginning Ryan’s musical education with the “Model Home Mix” burned CD she gives him in the second episode of the series. Quickly, though, it became clear that Seth was not only the heart of the show but also the stand-in for its sonic sensibilities. Through Seth’s adamant defense of his beloved Death Cab against Summer’s accusation that it’s “one guy and a whole lot of complaining,” and the Ben Folds Five posters in his room (and, by contrast, Ryan’s love of Journey), Schwartz essentially wrote a love letter to the soundtrack into the show’s own dialogue. (Marissa as music fan was not totally abandoned; the shot of her reading Please Kill Me: The Uncensored Oral History of Punk Rock in Season 2 is both perfect and extremely funny.)

Seth’s brief tenure as the Bait Shop’s worst employee tied it all together. By Season 2, the venue was very well booked: The Walkmen, the Killers, Modest Mouse, Rachael Yamagata, and even Death Cab all performed on the show.

Unlike Schwartzman, Yamagata told me that, by the time she was featured as a performer at the Bait Shop, the show was big enough that she had no reservations about saying yes and considered it a coveted position. Where Schwartzman had gotten to read a script before agreeing, Yamagata recalled that she wasn’t allowed to know what was happening in the episode she would be part of, even when she was on set. As she sang “Reason Why” and the crew filmed the 11th episode of Season 2, she said she couldn’t help but be distracted by what it could have meant that Mischa Barton as Marissa and Olivia Wilde as Alex were walking together toward the stage and holding hands.

“I’m like, ‘Oh my God, these guys are gonna get together. Am I the song that’s going to introduce a relationship?!’” Yamagata said. “So I remember sitting, being up there and trying to sort of hold my composure and be in the song and performing and also, like, flipping out in my head about ‘Oh my God, what is the scene about, are they getting together? This is so cool.’”

Yamagata said that “Reason Why,” though not a single or a highlighted track on her 2004 album, Acoustic Happenstance, remains a fan favorite. Both she and Schwartzman said they frequently hear from listeners who discovered their music through the show.

“It was kind of like it became its own genre of exposure during those years,” Yamagata said. “It was just at the beginning, but you did have a sense that there was this curation happening that was going to be very meaningful.”

By the time The O.C. ended in February 2007, Patsavas was already putting her musical stamp on Grey’s Anatomy as well. And she and Schwartz quickly reunited to create the soundtrack for Gossip Girl, another privileged-teen drama, which opened to the sounds of Peter Bjorn and John as Serena van der Woodsen pulled into Grand Central in the fall of 2007. Gossip Girl had some of the same indie touchstones as The O.C., Rooney included, but incorporated more pop and hip-hop—a little B.o.B here, a little Sia there—for city-slicker flair. And while you may have never heard of Cyrus Rose before, Lady Gaga certainly has, and Patsavas still has the ladder Mother Monster used while performing “Bad Romance” in Season 3’s “The Last Days of Disco Stick.” Then came her work on the Twilight movie soundtracks, in partnership with Paramore’s Hayley Williams, and the music supervision for Mad Men. In 2020, Patsavas joined Netflix to head up the music for its original shows, and her supervision led to the classically arranged pop soundtrack to Bridgerton and the follow-up soundtrack to Queen Charlotte, which features songs by Black woman artists.

Each of these shows has had a signature sound. The Gossip Girl soundtrack was distinct enough that last month, when Taylor Swift released “I Can See You,” a previously unpublished song from 2010, fans immediately identified it as a sonic fit for the CW show and made TikTok videos with Swift’s vault track as if it had been. But what has tied these shows together over two decades is Patsavas’s superpower: fitting the idiosyncratic pick seamlessly into peak monoculture. Especially as a part of projects aimed at female audiences, who don’t always get that kind of tasteful consideration, the combination can be genuinely thrilling—I’m not sure I can describe the excitement of hearing Muse’s “Supermassive Black Hole” for the first time while Robert Pattinson played vampire baseball, but I think about it regularly. Yamagata had her own version of this phenomenon: “You look back and you’re like, ‘Shit, Alex put Radiohead in the Twilight series. How did that happen?’” Yamagata said. “You look at her and you’re like, ‘This is a rock star.’”

Of all the listings on her IMDb page, Patsavas’s trademark work probably comes down to The O.C. or Grey’s Anatomy. These were the shows that did the most to introduce new artists and were the ones that aired in the peak years of music licensing for TV. For me, though, the pinnacle is The O.C. Grey’s would be a far worse show without its soundtrack, but The O.C. simply wouldn’t work at all without its music. One reason medical dramas—much like cop shows or mob movies—make good TV is that the life-and-death scenarios provide built-in high stakes. Conversely, one of the challenges of making a good teen drama is the need to manufacture high-stakes scenarios without destroying the characters’ relatability or becoming exclusively tragic. In this regard, The O.C. took viewers on a wild ride.

In the course of Season 1’s 27 episodes alone, Julie Cooper hooks up with members of three different generations (her husband, Jimmy; Kirsten Cohen’s father, Caleb; and Marisa Cooper’s teen boyfriend Luke); Ryan gets in at least five fistfights and steals several cars; multiple federal agencies decide it’s no big deal that Jimmy Cooper stole millions of dollars; and Seth manages to be both friendless and completely charming. To love The O.C. was often to accept wild, sudden, and sometimes contradictory plot swings into your heart, and the magic of the soundtrack was how it could smooth all that over.

Music could help sell the emotional truth—that Luke is a good guy now; that Marissa and Alex are a couple—better than more painstaking narrative setups would have. In other words, when you’re too emotional to talk, mmmm whatcha say.

Patsavas said that even in real time, it was easy to tell The O.C. was a special phenomenon. “I think I knew what a rare opportunity it was even while I was in it,” she said. She, Schwartz, and several of their coworkers remain friends, and they’re not above reveling in their own nostalgia once in a while: This fall, they have tickets to see Death Cab on tour together.