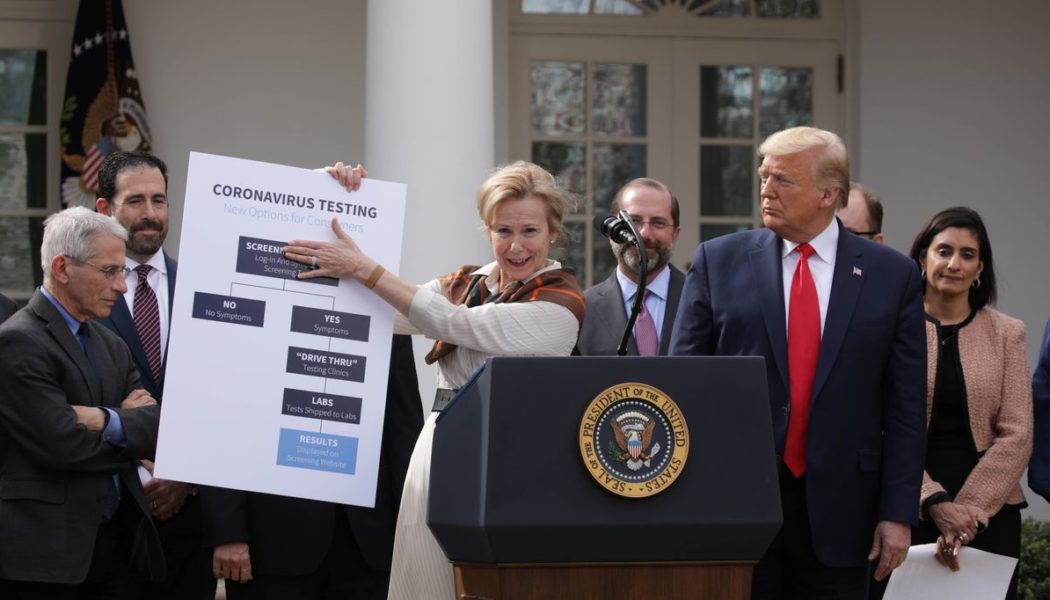

Two days after the World Health Organization declared that the coronavirus outbreak was a pandemic, then-President Donald Trump stood in the Rose Garden next to a flow chart. The chart promised that soon, it would be easy for anyone in the United States to get tested for the virus. According to Trump, Google was building a website to streamline the entire process.

It was the first of many promises that private companies would swoop in and rescue or bolster the country’s flailing COVID-19 response. Public health infrastructure in the United States has been underfunded for decades, and its underlying tech infrastructure is outdated and clunky. Health departments relied on fax machines and paper printouts to ferry data around. Fighting the pandemic would require a clear view of how many people were sick and where those sick people were, but the US was flying blind.

It seemed like Big Tech, with its analytic firepower and new focus on health, could help with these very real problems. “We saw all over the papers: Facebook is gonna save the world, and Google’s going to save the world,” says Katerini Storeng, a medical anthropologist who studies public-private partnerships in global public health at the University of Oslo. Politicians were eager to welcome Silicon Valley to the table and to discuss the best ways to manage the pandemic. “It was remarkable, and indicative of a blurring of the boundaries between the public domain and the private domain,” Storeng says.

Over a year later, many of the promised tech innovations never materialized. There are areas where tech companies have made significant contributions — like collecting mobility data that helped officials understand the effects of social distancing policies. But Google wasn’t actually building a nationwide testing website. The program that eventually appeared, a testing program for California run by Google’s sibling company Verily, was quietly phased out after it created more problems than it solved.

Now, after a year, we’re starting to get a clear picture of what worked, what didn’t, and what the relationship between Big Tech and public health might look like in the future.

Tech companies were interested in health before the pandemic, and COVID-19 accelerated those initiatives. There may be things that tech companies are better equipped to handle than traditional public health agencies and other public institutions, and the past year showed some of those strengths. But it also showed their weaknesses and underscored the risks to putting health responsibilities in the hands of private companies — which have goals outside of the public good.

“Big tech companies can be extremely useful,” says Andrew Schroeder, who runs analytics programs at the humanitarian aid organization Direct Relief. “The question is, how do you make sure that designing with the public good in mind actually happens?”

Understanding the problem

When the pandemic started, Storeng was already studying how private companies participated in public health preparedness efforts. Over the past two decades, consumers and health officials have become more and more confident that tech hacks can be shortcuts to healthy communities. These digital hacks can take many forms and include everything from a smartphone app nudging people toward exercise to a data model analyzing how an illness spreads, she says.

“What they have in common, I think, is this hope and optimism that it’ll help bypass some more systemic, intrinsic problems,” Storeng says.

But healthcare and public health present hard problems. Parachuting in with a new approach that isn’t based on a detailed understanding of the existing system doesn’t always work. “I think we tend to believe in our culture that higher tech, private sector is necessarily better,” says Melissa McPheeters, co-director of the Center for Improving the Public’s Health through Informatics at Vanderbilt University. “Sometimes that’s true. And sometimes it’s not.”

McPheeters spent three years as the director of the Office of Informatics and Analytics at the Tennessee Department of Health. While in that role, she got calls from technology companies all the time, promising quick fixes to any data issues the department was facing. But they were more interested in delivering a product than a collaboration, she says. “It never began with, ‘Help me understand your problem.’”

Before the pandemic, tech companies tended to assume that one data problem was the same as another, McPheeters says. Broadly speaking, they didn’t appreciate how important it was to understand epidemiology and public health in order to work with the data in that field. During her tenure at the department of health, for example, she oversaw efforts to develop a data-driven response to the opioid epidemic in the state. “We’d have folks come in and say, ‘We can solve your opioid problem because we’ve solved bank fraud before,’” McPheeters says. While there may be similar data science involved, the social environment on the ground — how people were behaving, and why — is just as important as the data itself. In that respect, there aren’t many similarities between the two.

This isn’t to say that there can’t be data-driven solutions to public health problems. Tech companies can have important roles to play during infectious disease outbreaks, like offering data-crunching expertise or platforms to analyze information. But companies have to work as partners, not outside disruptors, McPheeters says. That’s hard to do on the fly during an emergency when there hasn’t been a history of collaboration. “One of the challenges of a situation like this pandemic is that if you haven’t built those relationships already, it’s very difficult for those relationships to suddenly flourish,” she says.

Bigger barriers

Even without a history of robust collaboration, governments were eager to welcome tech companies to the table during the early phases of the pandemic response. When COVID-19 took hold in the United States, the country’s public health infrastructure had been crumbling for years. Underfunded and understaffed health agencies worked on outdated data systems and didn’t have the resources to invest in new ones. Many test results were still sent on fax machines.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22622426/1207061487.jpg)

Faced with the typical levels of public health problems, the systems could keep themselves together. But under the strain of a devastating pandemic, the cracks split. There weren’t reliable ways to send information on cases, hospitalizations, and deaths between hospitals, labs, and health agencies. Health officials didn’t have the resources to monitor the spread of disease.

Scrambling, officials took tech companies up on offers to take on some of the burden. “They got handed the keys to the kingdom,” says Jorge Caballero, an anesthesiologist at Stanford University and co-founder of the volunteer group Coders Against COVID.

Some of the first pandemic problems tech companies tried to tackle were COVID-19 testing projects. Google sibling company Verily piloted a testing system in California in March 2020, and eventually inked $55 million in testing contracts with the state. “They started off with this big overture that they could offer a turn-key solution to the state of California,” Caballero says, and to other states, as well. But by October 2020, two counties phased out the Verily testing program over concerns that it was asking for too much patient data and wasn’t accessible to low-income groups that had the greatest need for testing. The state’s partnership with Verily ended in February.

Google also wanted to link people to testing sides nationwide, and testing sites started showing up in Google searches at the beginning of April 2020. The company pulled in location data from state governments and groups like Castlight Health, which had its own testing site directory, Hema Budaraju, director of product management at Google, tells The Verge.

That Google project was technically a success — someone could search for a testing site and find one. But there was a problem with the approach, Caballero says. Any changes to testing site data would take a few days to update. But many COVID-19 testing sites, particularly those targeted at underserved communities, were temporary pop-ups. The lag meant those wouldn’t show up in search. Caballero tried to flag that issue to Google in spring 2020 but says he wasn’t impressed with its response: it took Google a long time to acknowledge the concern, and even then, he says it didn’t seem to him like it fully understood the issue.

Budaraju tells The Verge that Google relied on its partners to provide accurate testing site information, and that it makes updates if those partners flag any missing locations.

Health experts are always concerned that a push toward high-tech solutions would widen inequities rather than alleviate them. If Google wasn’t including pop-up testing sites or was updating them on a lag, people who live in areas without many medical resources — which were targeted by those pop-up sites — may have had a harder time finding them.

After someone tests positive for COVID-19, the next step for health officials is to identify the people who that person had been in contact with to encourage them to quarantine or get tested themselves. Tech companies thought they were positioned to help with that, too.

One of the flashiest attempts tech companies made to fight the pandemic was the Google and Apple exposure notification program. The companies teamed up on an app-based system that utilized Bluetooth to keep tabs on which smartphones spent time near each other. Then, if someone tested positive for COVID-19, they could alert strangers whose phones had been nearby.

In theory, this could help track down people who had been exposed to COVID-19 but wouldn’t have been identified by traditional contact tracing, which relies on sick people remembering everyone they’d been in touch with while they were contagious. “There was a naivete about it,” Storeng says. “Wouldn’t it be awesome if I could just be notified when I’m exposed to infection, and that can solve it all?”

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22161150/1290167857.jpg)

In the end, evidence on the system was mixed. In the United States, only a small percentage of people used apps built on the system — likely not enough to make a difference in the trajectory of the pandemic. In the United Kingdom, where a quarter of the population signed up, researchers estimated it helped avert hundreds of thousands of COVID-19 cases.

All of the data, though, are estimates: because of the app’s focus on privacy, officials around the world can only extrapolate from the number of people the app notified about a possible exposure. There’s no way to know if people who got those notifications actually isolated themselves or got tested for COVID-19. Without that data, officials can’t evaluate how many infections the exposure notification programs prevented. It also meant that they weren’t able to learn who was notified about a possible exposure, let alone get in touch with them to offer support or resources. That information stayed in the app.

It’s an example of a tech company building a digital system without incorporating the most important elements of the manual program it’s attempting to augment. McPheeters says that contract tracing can’t be as effective if there isn’t any connection to the people who were exposed. “If you look at the history of contact tracing and you talk to experienced contact tracers, it’s actually about relationship building,” she says. “It’s not about tracking.”

Finding lanes that work

There are success stories from the past year. One clear bright spot was mobility data. Companies like Facebook and Google tracked how people’s movement patterns changed in response to social distancing policies. Before the pandemic, there hadn’t been anything like the sweeping stay-at-home policies introduced by governments around the world.

“This was really chaotic. Nobody really knew what was going to happen, or if anyone would listen to these policymakers,” Schroeder at Disaster Relief says.

Google started releasing COVID-19 Community Mobility Reports in April 2020, and Facebook pushed out similar information through its Data for Good program, which builds datasets in partnership with humanitarian organizations and academic research institutions. That helped researchers understand how people’s behavior changed under new policies. “It went from flying blind, to not flying totally blind,” Schroeder says.

Seattle area researchers used Facebook’s data for one of the earliest looks at how movement patterns affected the spread of COVID-19. Other cities, like New York City, used the information to tailor their public health response. The data also informed academic research on COVID-19 over the past year.

Tech companies are the only resources for this data, Schroeder says. “There’s no government anywhere that’s producing this, no nonprofit producing it — if you want that information, the only way to do that is through one or another private tech company.”

Through Data for Good, Facebook also started running large-scale surveys in partnership with academic researchers. One project, the KAP COVID dashboards, was a collaboration with the John Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health and the Massachusetts Institute of Technology. The group surveyed people in 67 countries about their COVID-19 knowledge and pandemic behaviors. Facebook provided the platform, and the researchers designed the survey.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22624424/1212276796.jpg)

“It’s a phenomenal resource. There’s really nothing like it,” says Douglas Storey, a professor at the Johns Hopkins Center for Communication Programs working on the project. The team has used its findings to run webinars with working groups in the countries it surveys and to share information about how people are modifying their behavior to prevent COVID-19 spread. The team has started to incorporate questions on vaccine acceptance, as well. Then, countries can use the information for their own pandemic response strategies, Storey says.

The Data for Good team was eager to work with the scientists, he says, and seemed to have a clear sense of the areas in which it didn’t have expertise. “They seemed genuinely committed to understanding how they can have a more positive impact.”

These enormous, worldwide surveys could only really be done by big tech companies like Facebook. “Facebook, every single day, is surveying hundreds of thousands of people all over the world,” Schroeder says. “Could any government run a survey, daily, globally, at that scale? The UN doesn’t have the ability to do that, and they’re the only ones who would have the authority globally.”

Notably, Facebook and Google weren’t doing their own interpretation of this data — they supplied it to public health experts and left them to do the epidemiology. That’s an important part of the Data for Good approach, Laura McGorman, policy lead on the team, said in a statement to The Verge. “Our partners provide the domain expertise required to make use of these tools to solve real-world problems — whether it’s in public health, natural disaster response, or climate change. This work is extremely collaborative and plays to the unique strengths of everyone involved,” she said.

It’s different from, for example, the exposure notification program — where Google and Apple built a self-contained product that collected and used data. In the recovery from the pandemic, as tech companies continue to push into healthcare and public health, there’s an open question around which approach will win out.

“What is the role Big Tech should play as a neutral data publisher, and what role should it have in terms of producing something where analysis has already been done?” Schroeder asks.

Planning for the future

Despite the mixed record on tech contributions during the COVID-19 pandemic, coalitions of companies are gearing up to keep pushing into healthcare. It’s a hugely lucrative area that they were already interested in before the pandemic — the healthcare market is a nearly $4 trillion industry in the US alone. Last summer, for example, the Consumer Technology Association (CTA) launched the Public Health Tech Initiative, a working group that includes CVS, Facebook, Microsoft, and other major players. It plans to analyze the things that did — and didn’t — go well for tech companies during the pandemic and leverage that experience to prepare for the next health emergency.

To start, the group is focusing on health data and virtual care, says René Quashie, vice president of digital health at the CTA. Members are talking about projects like an early warning system for public health that aggregates data from wearables, or creating data sharing platforms for public health agencies.

“We would envision sort of a new paradigm, more of a public-private partnership where public health agencies and government bodies are able to leverage the technological expertise of the private sector,” Quashie says.

Some experts remain wary about the implications of integrating the private sector even more tightly with public health. Public health is supposed to be just that: public, and governed with the public good in mind. “What is a public good coming from private companies?” Schroeder asks. “Could you have some kind of structure that draws on what they’re good at, but doesn’t turn the authority over to them? I have no idea.”

The goal of public health is to make a community healthier, not just individuals. Everyone shares in the success of reducing the spread of a disease like COVID-19, for example — no one is excluded from the benefits of lower levels of disease, even if they don’t personally contribute to reduction efforts. Turning a public health task over to a private company could turn the overall goal of a project away from the pursuit of a collective good and toward accomplishments that would benefit the company. It may also lead to collective good, but that might be secondary.

Companies that used their resources to fight COVID-19 got something out of it. Whether it was lucrative contracts, good PR, or even just helping their customer base stay healthy — it benefits companies to participate when the world’s health is on the line. As the emergency of the pandemic recedes, companies’ motivations to venture into public health and healthcare may change — and consumers and governments should pay attention to that changing landscape, experts say. “Does it have anything to do with health improvement, or is it about something else? Is it a way for these companies to harvest data, or get entry into new markets, or just some corporate social responsibility scheme to enable other kinds of activities?” the University of Oslo’s Storeng says.

The mobility data, for example, was a huge boon to researchers through the pandemic. At first, many companies were giving that information away for free. “Now, it’s like, ‘About that free price,’” Schroeder says. He isn’t expecting Facebook to put up any paywalls. “The profit or loss on the mobility data or the survey data is a rounding error for Facebook,” he says. But it’s more of a concern for the smaller companies. Mobility data company SafeGraph, for example, offered its data for free to government agencies and nonprofits early in the pandemic but is now charging those users for data again.

But it shows the tension created by relying on a private company for a critical public health service: it could, at any time, decide that it no longer wants to provide it to researchers — or it could decide that that valuable information comes with a price; private companies, after all, are first and foremost in the business of making money. Or, health officials have to make compromises on the terms and conditions around the data, as with the Apple and Google exposure notification program. “These are companies that have been known to be monopolistic, and potentially antithetical to democracy and free speech,” Storeng says. “You have to ask skeptical questions about the legitimacy of their involvement.”

The pandemic highlighted the underlying weakness of the US public health system, particularly around its data systems and tech infrastructure: they’re outdated, disjoined, and underfunded, which leaves the country vulnerable to infectious disease threats. The past year opened the door for the tech industry to tackle some of those problems. Regardless of concerns around the companies’ intentions, it will likely stay open — and companies have made their interest in the space clear over the past few years. They may be able to make useful, lifesaving contributions, but the public good still has to be the priority.

“What is really clear, and I think this was clear well prior to the pandemic, is that tech does not substitute for strong public institutions,” Schroeder says. “Public health investment needs to happen independently of what any tech company does.”