“Dad’s coat,” one bubble reads. “Brother’s shirt, Mom’s pants,” read little arrows, tracing the origins of the tuxedo flailing across the screen. The belt, however, belongs to the body it’s on. As does the song it dances to and these helpful tidbits from the accompanying “pop up” music video — all from the restless imagination of Abhinav Bastakoti, aka Curtis Waters.

“Curtis Waters as a whole project has been around since I was a kid, a comic book character that I used to draw,” he tells SPIN. “I wanted it to feel like an alternate universe where there’s this character, but it gets kind of blurry now ‘cause I’m Curtis Waters full time.”

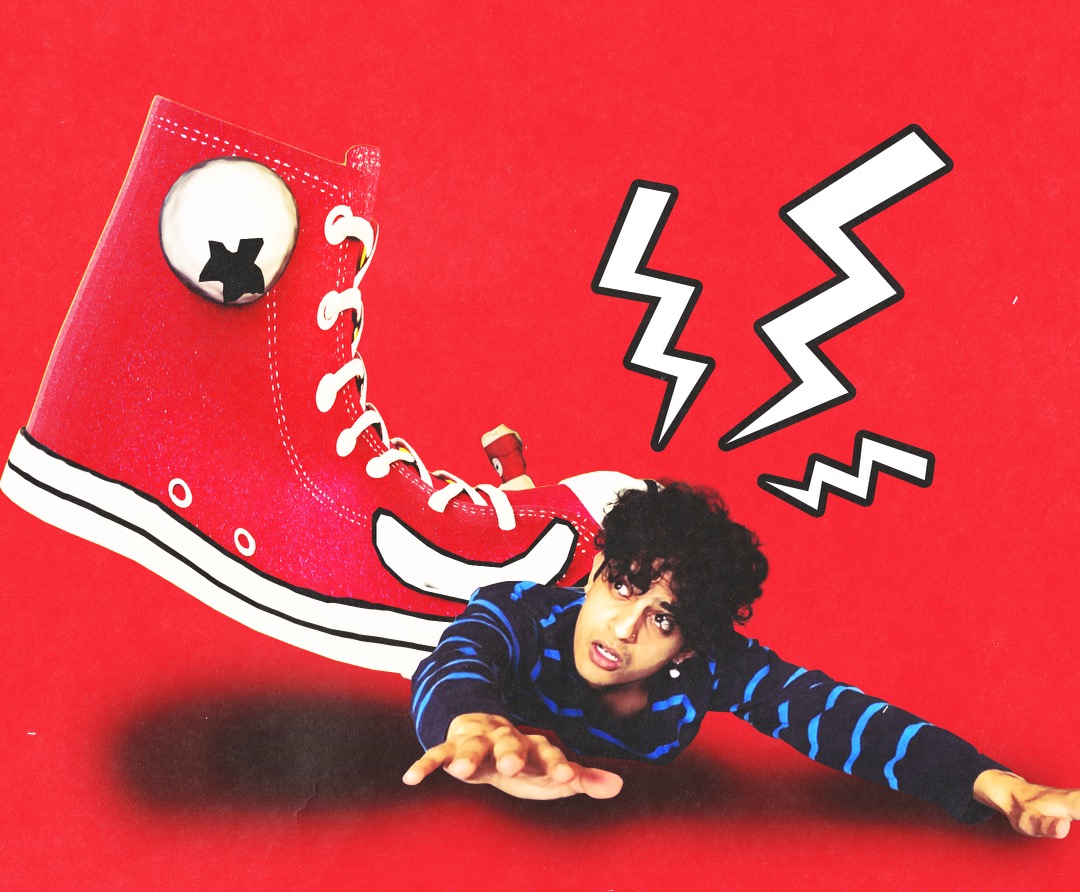

Waters was propelled into the shoes of his persona by the success of his single “Stunnin,’” featuring his longtime friend Harm Franklin. Accumulating over 154 million Spotify streams as of this writing, the song now may help him realize those childhood fantasies.

Having just inked a licensing deal with BMG, the 20-year old is diving into the habits and pleasures of his career. “I’m already working on new stuff,” he says. “I’ve got new instruments. I play bass; I play piano. I have the luxury of just being in my house and making music all day.”

“Stunnin’,” which first brought Waters to the attention and pestering of label reps, is a testament to his ear: The song’s floaty pop instrumental is the perfect home for his carefree flow and Franklin’s breathy vocals, and the track itself is suited to the TikToks he used to promote its release — brief, loose dance routines that would be imitated in the Superbad-intro visuals of its music video.

As pivotal as the song has been to his burgeoning career, he doesn’t take it too seriously. “I wasn’t even gonna put it on the album,” he says, and a closer listen to the song’s gratuitous verses explains why Waters referred to it as “the most elaborate dick joke of all time.” And despite its distinguishing success, the video’s intro — which sees Waters squatting on a desk, the green screen behind him not yet pulsing out pastels and parted lips — reveals, even celebrates, the ordinary conditions in which the song was made.

Several of Waters’ videos were produced in his garage, exemplifying his desire to change or escape a difficult environment. Having struggled to fit in through moves from his birthplace in Nepal to homes in Germany, Canada and, finally, North Carolina, and then receiving a diagnosis for bipolar disorder, Waters’ feelings of isolation and rejection take shape across his debut LP, the coming-of-age Pity Party. “The album was just for me to cope,” he says. “I was diagnosed in college. I went back home. I was working a minimum-wage job, and I felt like I was going nowhere in life. I was really worried.” The album’s last single “The feelings tend to stay the same,” which Waters has revealed was a letter to an estranged college friend, highlights this fragility.

The project’s production mostly echoes “Stunnin’”s bright pop sensibilities but, drawing from the pop-punk he grew up on, matches them with more pessimistic lyrics. “From tying my shoes to tying the noose / Too many choices — how can I choose? / Life is a race; I’m scared to lose / I’m paralyzed; I’m hitting snooze,” he flatly sings through the droll melody of “Shoelaces.”

At the start of both tracks (and then again and again throughout the album), you can hear his production tag “Good job, Curtis!” You’ll also see his name in the credits of the video. “I used to do everything myself,” he says. “All the production, the directing, the mixing and mastering. It’s been really hard to let go.” On Pity Party, Waters is a co-producer on every track, but Declan Hoy (aka Decz), another longtime friend and collaborator, lends a hand on “Stunnin’” and “The feelings tend to stay the same.”

His BMG deal — which will give him ownership of his masters after 10 years — reflects his commitment to controlling as much of his art as possible. As does the less pop/more punk “System,” whose chorus chant of “I’m not your product” is a sharp response to other labels undercutting his freedom.

But having found terms to his liking, Waters now has a world of discovery and experimentation ahead of him.

“I could go the route of making a bunch of hits like ‘Stunnin’,’ but it would be a disservice to the kid that worked so hard to make this happen. I took all those anxieties and made an album out of it so other people could see it and know they could do it too. Making music is just this cathartic act.”