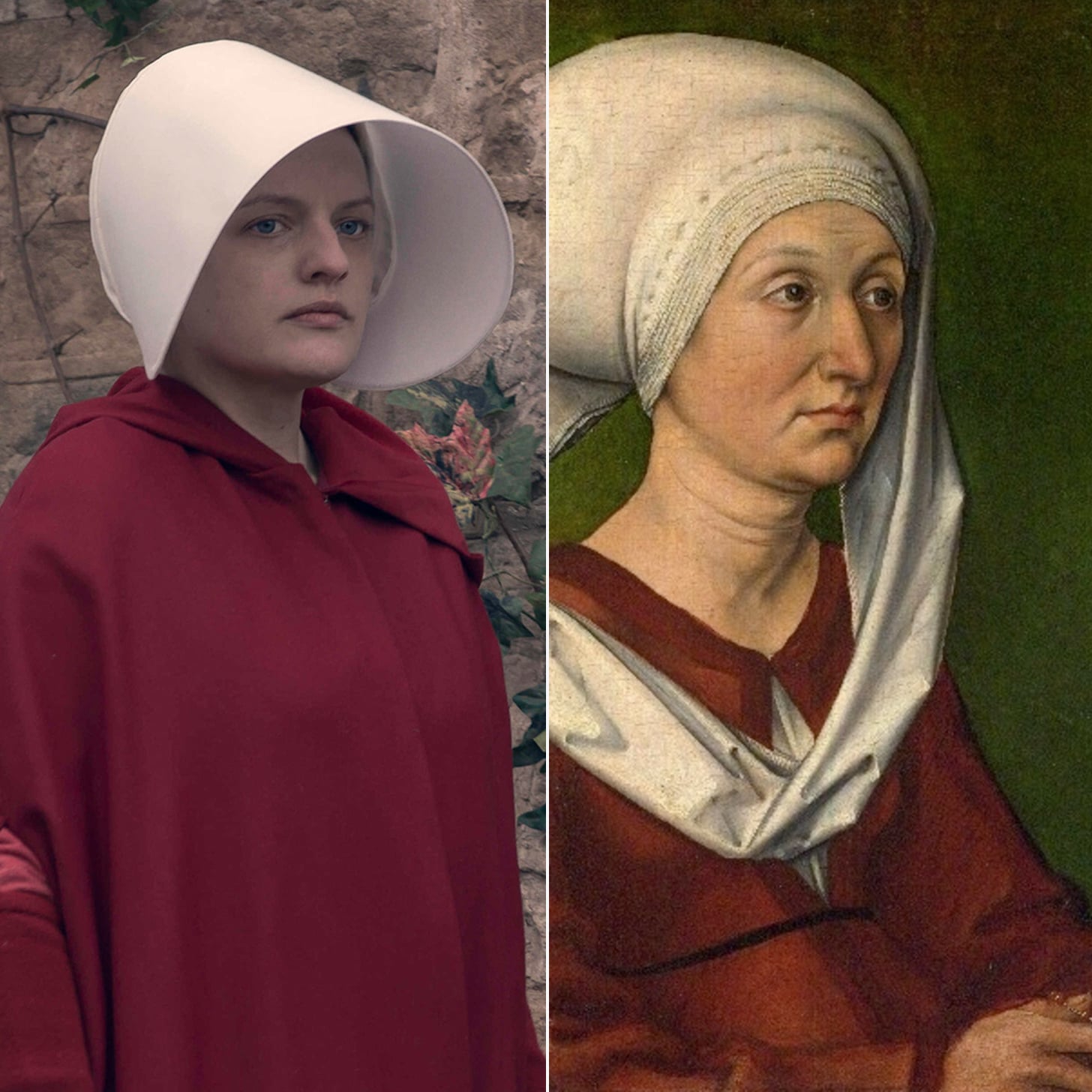

Left: June Osborne ( Links”>Elisabeth Moss); Right: Portrait of Barbara Dürer by Albrecht Dürer

Natalie Bronfman is the two-time Emmy-nominated eye behind the costume design for The Handmaid’s Tale. Supervising the creation of the show’s iconic red-caped dresses and white bonnet hats since its 2017 debut, she more recently took over as lead costume designer for the show’s third season. Now that Bronfman is up for her third Emmy nomination, she speaks with POPSUGAR about the rich variety of design references that inspired season three of one of television’s most visceral drama series.

“It’s funny because I actually wanted to be an opera singer,” Bronfman admits, with a joyful demeanour in contrast with the dystopia she dresses, but it’s easy to see how her love for drama and theatrics shapes her eye for design. “I tend to like a post-war aesthetic, post Second World War, like [Federico] Fellini, that genre of films, and anything very historical. Even the original version of Cleopatra, which was so over-the-top with Liz Taylor, but you look at it and it’s such a visual eye candy that you can watch it 10 times and there are more things that you see.”

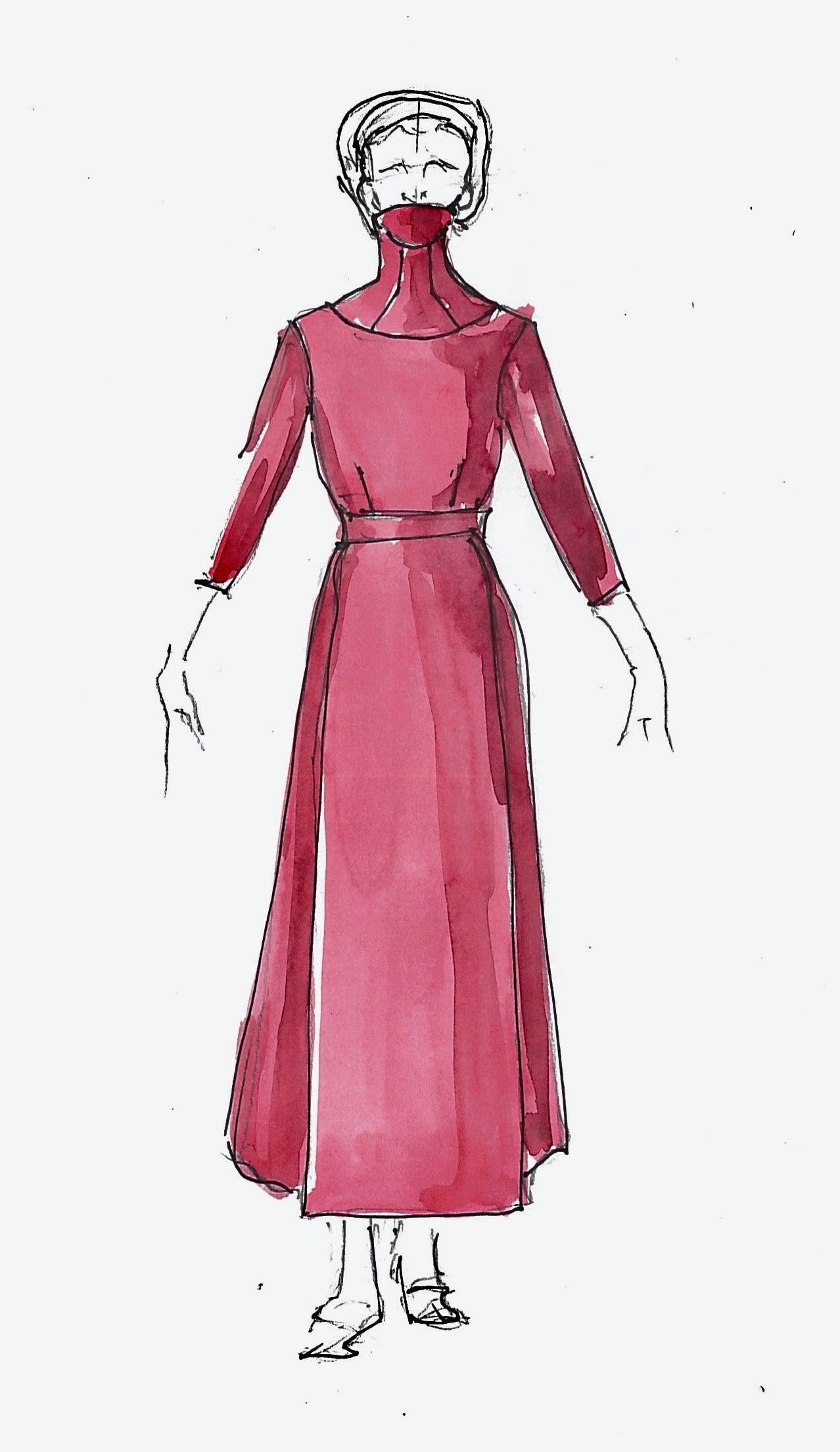

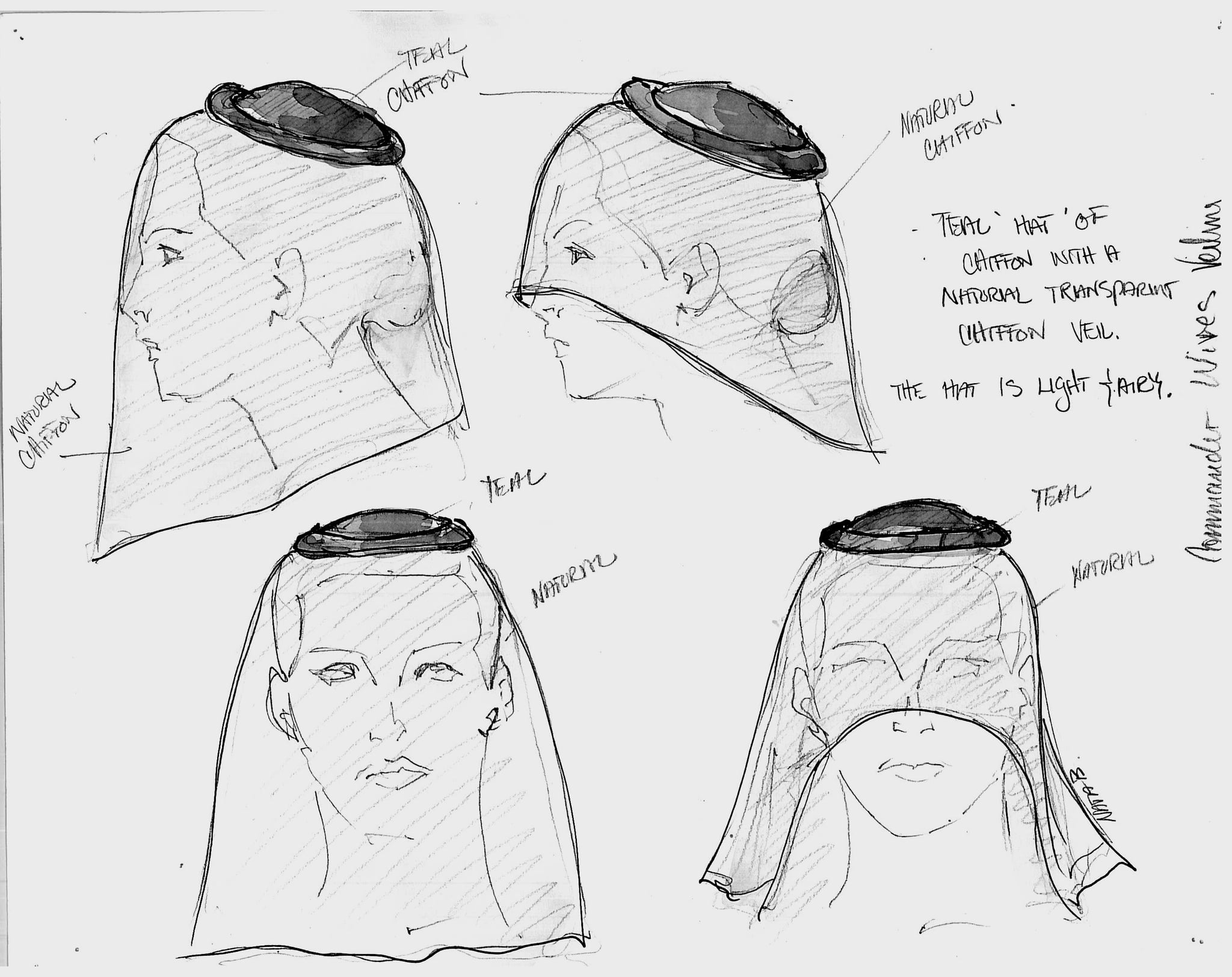

Natalie Bronfman illustrations for the commanders’ wives’ gowns in S3, Ep7

Natalie Bronfman illustrations for the commanders’ wives’ gowns in S3, Ep7

Bronfman’s historical approach to costuming is seen heavily in the prim-and-proper post-war silhouettes of The Handmaid’s Tale. For season three, the character’s dress — particularly that of June Osborne (Elisabeth Moss), Serena Joy Waterford (Yvonne Strahovski), and Fred Waterford (Joseph Fiennes) — takes a much more sinister turn when the storyline moves to the austere state of Washington.

“In season three, I had the fortune that the writers created a new city,” says Bronfman. “I could introduce new things because we were leaving Boston and going into Washington. Everything became more restrictive. The veils, the rings, even the clothing, everything was now covered up. There was no more neckline that was exposed. I put the wives into a 1950s shape, because it’s sort of that archetype — he walks through the door, she hands him a martini, and don’t talk to me about my day.”

Illustrations for the handmaids’ costumes in Washington

Illustrations for the handmaids’ costumes in Washington

“When Serena started out in season three, she had lost her baby, so her shapes were very frumpy because it was hand-me-down clothing after she had set her house on fire. She had nothing, and slowly, slowly, she comes into strength again by her clothing changing tonality and brightness. The very last teal commander’s wife dress we see her in is the brightest she’s ever worn, and she misleads her husband by the way the clothes look. I took her from that sort of ’50s housewife shape, and brought her into things that were very tight to the body, almost like an armour.”

Illustrations for the handmaids’ capelets

Illustrations for the handmaids’ capelets

“With June, when the government was doing the propaganda, the handmaids wore little capelets that covered up the neckline, so that became a new costume piece. There was also an army that was introduced, and a new commander uniform, but it didn’t make it to camera for some weird reason or not in the final cut, but it was sort of influenced from various armies in the past.”

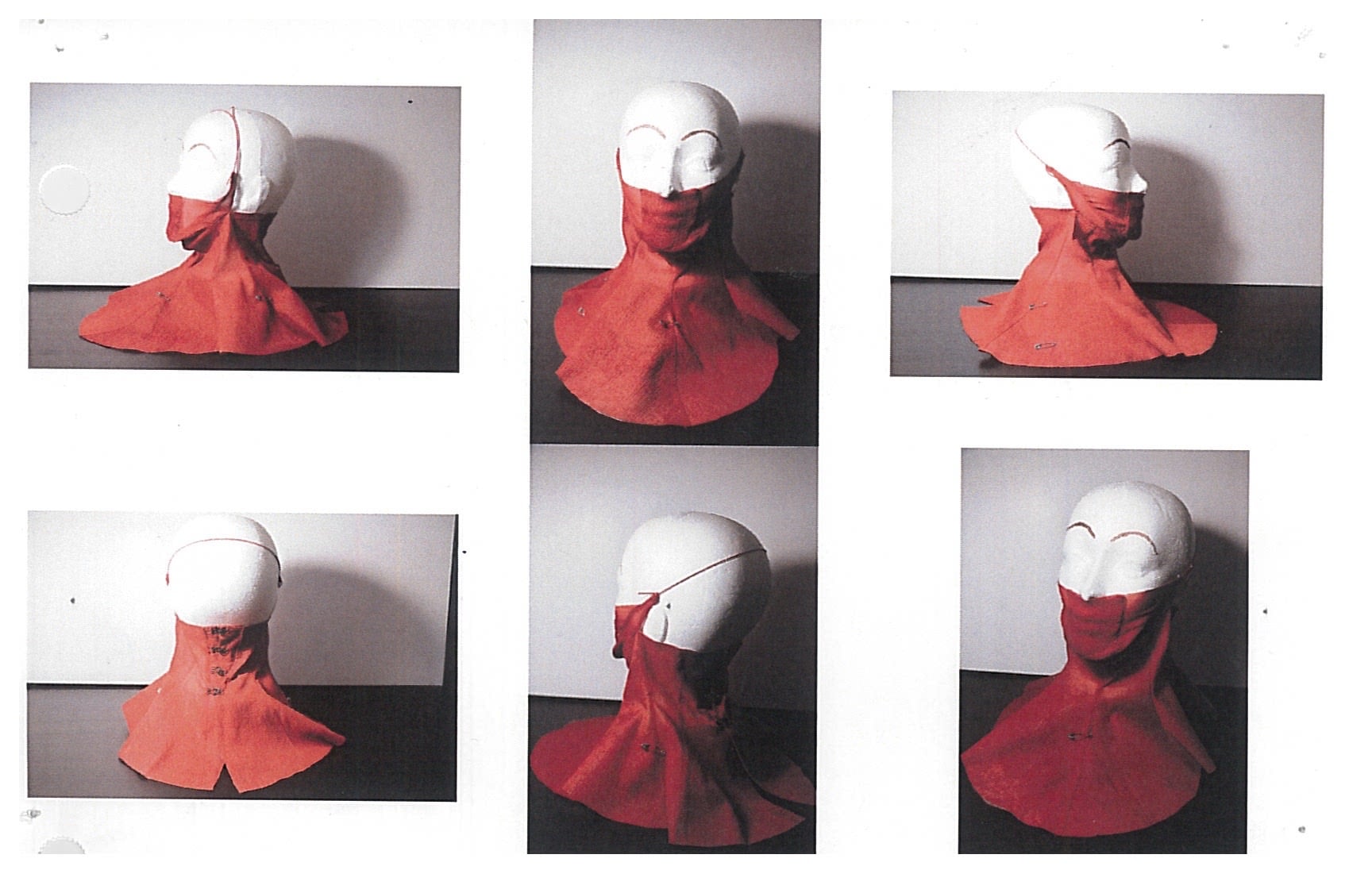

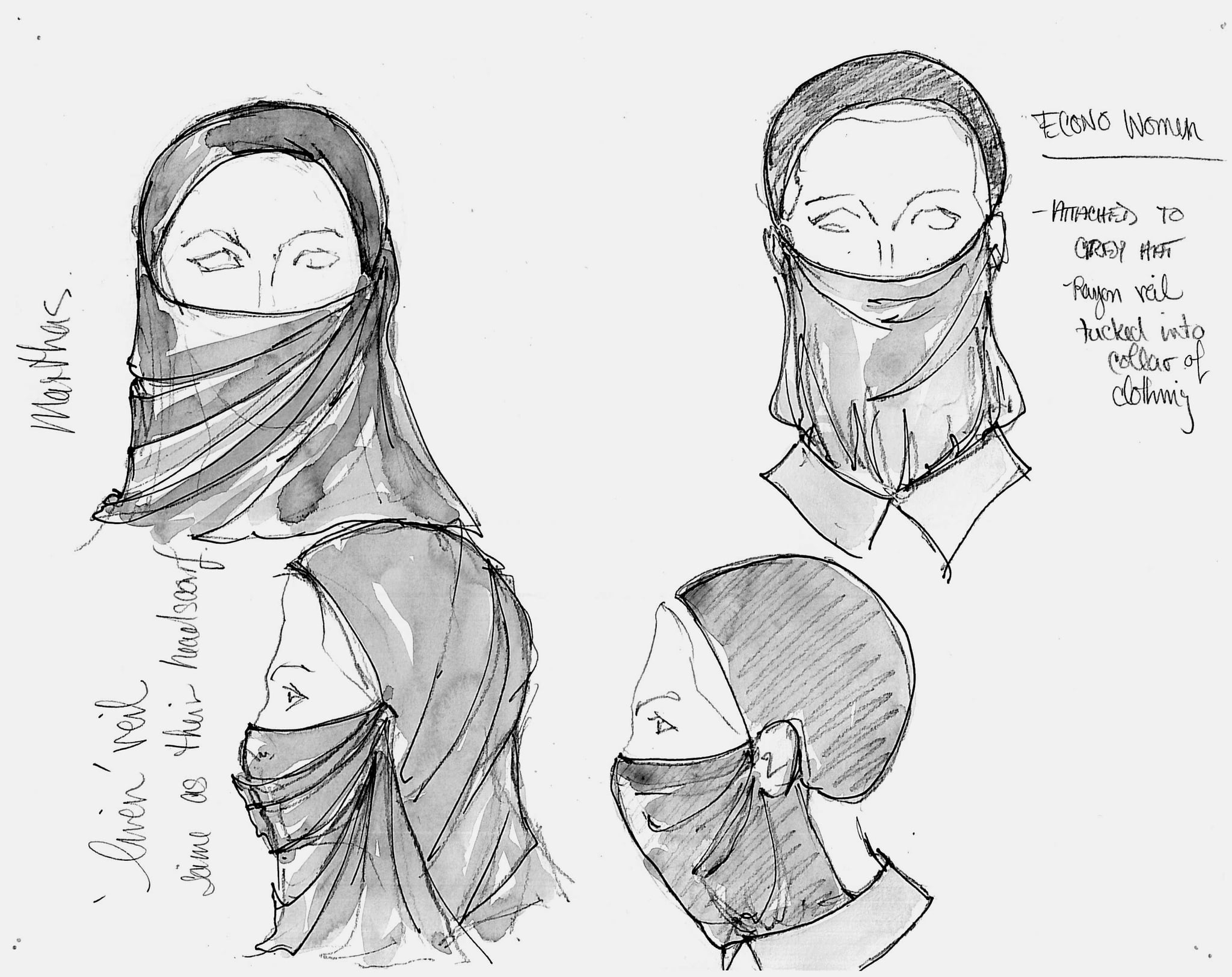

Prototype for the handmaids’ veils

Prototype for the handmaids’ veils

Season three dives into restriction and propaganda much more intensely than we’ve seen in previous seasons of The Handmaid’s Tale. The most striking expression of Washington’s austerity is seen in the newly introduced veils worn by the women of Gilead, which are inspired by an archetype from each of the four major religions. The veils worn by the handmaids and aunts are an under-dressing of a wimple, which is a cloth headdress still worn by some nuns that covers the head, neck, and sides of the face. “I took those from paintings,” Bronfman explains. “One was an Albrecht Dürer painting of his wife, and she’s got the wimple on, which covers her chin and her forehead. I played with that and made it cover up the mouth, which takes away the last thing that the handmaids had, their voice. There’s no more whispering between them going on, and you can’t instigate anything anymore. So it’s complete docility.”

Illustrations for the commanders’ wives’ veils

Illustrations for the commanders’ wives’ veils

The commander’s wives wore a version of the Jewish kippah hat with an attached veil. “This was a nod to being pious, because they were the jewels of the empire, so they didn’t really feel they had to participate. The Marthas’ veils were sort of the Middle Eastern head wrap that when they went out, they could just drape it. And the econopeople were essentially just tubes, utilitarian, that doubled up as collars because they were the worker bees of the empire.

Illustrations for the econowomens’ veils

Illustrations for the econowomens’ veils

Bronfman’s deeply historical approach to costume is fascinating because it gives a real artist’s insight into the symbiosis between life and art — how art is given context through our lived realities, and then the stories of our lives imitate art in return. “I was always looking to history because, even Margaret Atwood always said that, whatever happened in the book has already happened”, she says, and one could also consider that the masked reality we are currently living is following a very similar trajectory.