Writing about music is a strange and probably foolish thing to want to do, and attempting it is certainly not an activity that ever crosses most people’s minds. For the wayward souls who do set out to do it, there’s usually a writer or work that we encountered at a formative age and that made us think: Whoa, what if I could grow up to do that? For me, that writer was Dave Marsh, and the work was his 1989 tome The Heart of Rock and Soul: The 1001 Greatest Singles Ever Made, which a fellow music-obsessed friend lent to me when I was a young teenager in the mid-1990s. The book is over 600 pages long and is exactly as advertised: Marsh ranks what are, in his estimation, the 1,0001 greatest singles of the rock ’n’ roll era and writes essays about all of them.

I’d certainly read, and loved, plenty of music writing before that, but I had never encountered anything like The Heart of Rock and Soul. For starters, there was the sheer scope of the thing, from both a historical and stylistic standpoint. Here was a book that celebrated recordings as disparate as Big Joe Turner’s “Shake, Rattle and Roll,” Aretha Franklin’s “(You Make Me Feel Like) A Natural Woman,” and Van Halen’s “Jump,” not just within the same volume but remarkably close to one another (Nos. 13, 18, and 28, respectively). Its breadth of connoisseurship introduced me to music I probably wouldn’t have otherwise encountered in the pre-streaming 1990s, recordings that I would spend months and years seeking out and still love ferociously to this day: Clarence Carter’s 1969 “Making Love (at the Dark End of the Street),” a sui generis masterpiece that Atlantic Records buried on a B-side; or Otis Redding’s exquisite rendition of “You Left the Water Running,” a 1966 demo recording that wasn’t even released until 1976, and then only illegally.

But most of all it was about the writing. There’s an old adage in criticism that it’s easier to write about art you hate than art you love, and it’s often true: Hatred offers an easy way out of serious engagement, an excuse for polemicism and digression and getting off a few jokes. The Heart of Rock and Soul, on the other hand, is hundreds upon hundreds of pages of Dave Marsh writing about music he loves, and why. “ ‘I Heard It Through the Grapevine’ isn’t a plea to save a love affair; it’s Marvin Gaye’s essay on salvaging the human spirit,” reads the opening sentence to the book’s No. 1 entry, and somehow it gets better from there.

Among many other things, The Heart of Rock and Soul taught me that open-mindedness and discriminating tastes are not mutually exclusive propositions in criticism. Like all great critics, Marsh is unapologetically opinionated—he once infamously described Queen as “the first truly fascist rock band” in the pages of Rolling Stone—but the book is anything but a fusty canonization project. Though he was writing long before rockism and poptimism became common parlance (and even longer before they became clumsy epithets), Marsh’s objects of adoration run from Donna Summer to Derek and the Dominos, from Run-DMC to Patsy Cline, Elvis Costello to Cameo. Every time I revisit the book, I’m struck anew by how much Marsh’s writing shaped the way I think about music, how to listen to it and how to value it.

Kick Out the Jams: Jibes, Barbs, Tributes and Rallying Cries From 35 Years of Music Writing is a new collection of Marsh’s writing that offers highlights of his work since the mid-1980s, from venues ranging from the now-defunct Addicted to Noise to CounterPunch to Entertainment Weekly and, most frequently, Rock and Rap Confidential, the long-running monthly newsletter that Marsh began writing in 1982. The collection features a lovely introductory essay from music scholar Lauren Onkey and a postscript from Pete Townshend. As Onkey notes in her preface, among critics of his generation Marsh doesn’t hold the same prominence as Robert Christgau, Greil Marcus, or the late Ellen Willis and Lester Bangs. Kick Out the Jams should restore him to his rightful place in the pantheon of America’s very greatest music writers.

From its opening pages, the new book is a welcome reminder that Marsh writes about music and politics, in the broadest sense of that term, more directly and just flat-out better than almost anyone. The book’s first entry, from an address Marsh gave about Elvis Presley that was published in Musician magazine in 1982, rightly identifies Elvis—and, by extension, the cultural circumstances that birthed rock ’n’ roll itself—as a product of the New Deal, a program whose myriad provisions were, as Marsh takes care to repeatedly point out, being hollowed out by Ronald Reagan literally as he spoke. Throughout the 1980s, Rock and Rap Confidential raged against censorship in all its forms, from the Parents Music Resource Center hearings to Pepsi’s cowardly cancellation of an ad campaign with Madonna after religious groups objected to the imagery in her 1989 video for “Like a Prayer.”

The 1990s and 2000s find Marsh decrying the increasing corporate consolidation and rampant greed of the recording industry. In many of these essays, Marsh comes off as almost prophetic. From a 1998 essay on the growing industry panic over the still-novel MP3: “This is why it always gives me such a laugh when [Recording Industry Association of America lobbyist Hilary] Rosen and other industry propagandists start bellyaching about how stuff like MP3—like cassette tapes and DAT before it—is gonna ruin their ability to protect creators … The notion that the record industry, of all institutions, stands for the fair payment of people who do creative work is so blindingly false that you have to laugh.” It’s hard not to grimace reading these words 25 years on, as said industry now has happily climbed into bed with streaming services to screw artists out of compensation in newly high-tech ways. An essay on the homogeneity of country radio morphs into a screed against the deregulation of media ownership and its impact on programming diversity: “All across the radio spectrum, you can hear almost nothing but nothingness,” writes Marsh. “America’s radio is at war with America’s music.”

Not that anyone should mistake Marsh for some sort of moralizing scold. He’s the kind of music critic who makes you want to hear the world the way he does. I will confess to never having totally “gotten” the MC5, the band whose epochal 1969 single gives this book its title (Marsh ranked it 226th of all time in The Heart of Rock and Soul) and who are the subject of a terrific 1990 essay collected within it. But goddamn it if every time I read Marsh on them I don’t go scrambling back, desperately trying to find what I’ve been missing, certain that this time I’ll find it. (I haven’t yet, but someday I will.) Even moments of heretical dissent are often delivered with love: I found myself brought up short over a description of Frank Sinatra as “overrated in the way that only the very greatest can be overrated,” a perfectly phrased little bit of myth-puncturing.

And at the level of the sentence, few rock critics have been capable of a gut-punch like Marsh. In a 2013 essay remembering Pete Seeger, Marsh writes that his life and work demonstrated “that the world was packed with a load of insurmountable cruelty and that, nevertheless, the truth was that something better had managed to survive within it. Which meant, for each of us, a choice and a chance.” From a profile of Patty Griffin penned for the Austin Chronicle: “Her performance on ‘Be Careful’ turns those two words into an anthem, and not with a shout. Griffin sings them so delicately that the listener can’t avoid feeling the consequences of careless behavior with fragile souls.”

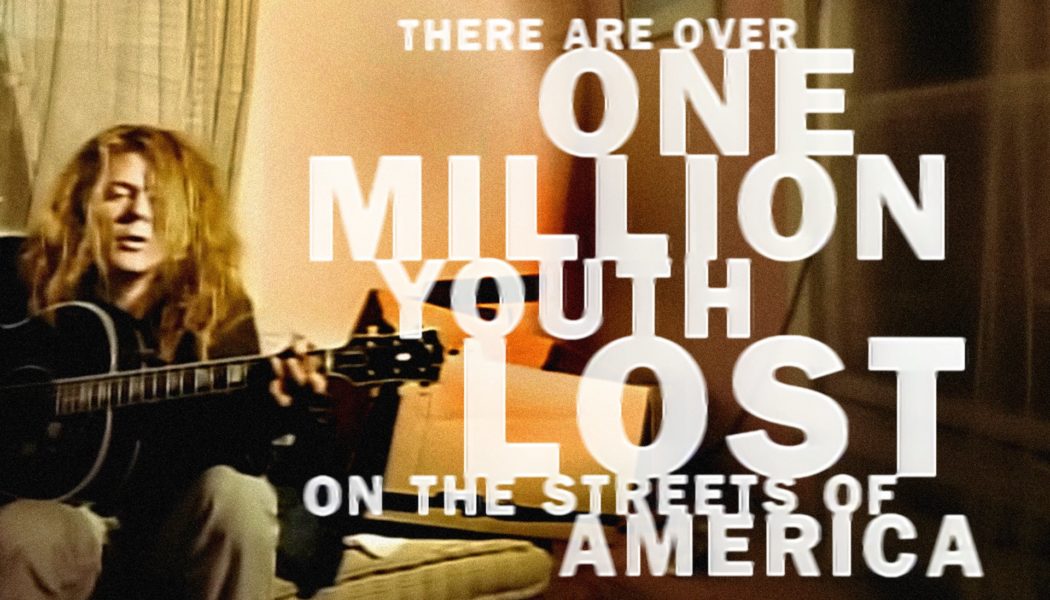

In Marsh’s work, music and empathy have always been inextricably intertwined: The value of one is in its potential as a vehicle for the other, and vice versa. An essay on Kurt Cobain’s suicide opens into a beautiful, heartbreaking rumination on the paradoxes of Cobain’s art: “In that end, Kurt Cobain may have found this the most frightening aspect of his whole life and career. He thought he was alone in what he felt, and it turned out that in feeling alone, he connected to just about everybody. Such a realization would scare almost anybody; having to live with a truly penetrating awareness of how isolated and beyond solace most everybody in our world feels could scare almost anyone to death.”

Kick Out the Jams reminds us how much of Marsh’s writing is concerned with connection and care, in all of its various implications. In 1993, Marsh lost his 21-year-old stepdaughter to a sarcoma, a rare form of cancer, and for decades he has helped raise money for research in her name by way of the Kristen Ann Carr Fund. Her memory comes up repeatedly through Kick Out the Jams, including in its last piece, a 2017 profile of Austin singer-songwriter Jimmy LaFave, who was dying of the same disease as Marsh was writing about him.

“Music can’t change the world,” writes Marsh in one of the later essays of Kick Out the Jams. “But sometimes, it delivers pretty great marching orders.” It’s a seemingly straightforward sentiment that I found myself dwelling on and admiring: Like music, marching is rhythmic, it moves us forward, it’s something people do together. Dave Marsh taught me that, at its best, music writing can deliver pretty great marching orders too.