I have a poster of a 1993 University of Vermont campus-radio-sponsored show featuring Fugazi and Shudder to Think. The caption, “Washington’s Fugazi Claims It’s Just A Band. So Why Do So Many Kids Think It’s God?”, is from a Washington Post article published around that time. That poster, along with one from an earlier station-sponsored performance by the Red Hot Chili Peppers, the Smashing Pumpkins and Pearl Jam, is displayed in my office at the Library of Congress.

In my basement is a stencil from KMFDM, whose accompanying can of spray paint helpfully advises DJs to refrain from defacing the program director’s car; as a vehicle-owning program director, I appreciated the admonition. Shortly after arriving on UVM’s campus in 1990, I visited their student-run radio station WRUV and, after being trained on the station’s turntables, CD players, and cassette decks, became a DJ playing heavy metal during a 2:00-4:00 AM time slot. A bit more than two years later, I became the program director after winning the position in the annual WRUV executive board elections.

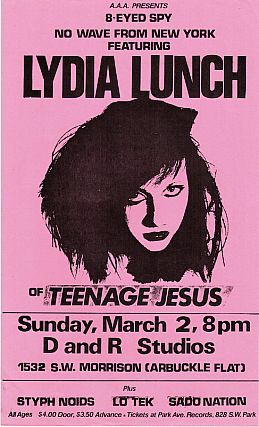

Parenthetically, the sheer amount of music-related paraphernalia was overwhelming; I doubt that anyone can remember the entire WRUV stock of posters and other promotional material. The Soundgarden Jesus Christ Pose votive candle was a personal favorite, as was a container of motor oil from Ministry to promote the band’s “Jesus Built My Hotrod” single (a music director allegedly used this substance in his car). I also recall a discussion with the station manager about possibly relocating a poster for Brutality’s Indecent and Obscene album.

A WRUV show was an unparalleled experience for a younger music enthusiast. Consequently, DJs had a near-infinite universe of music from which to choose. Of course, accessing WRUV’s music is why DJs were there. The quantity from which to choose made putting together a show fairly easy. WRUV boasted the largest music library in Vermont – a music nerd’s candy store. All of the records and CDs, which took up what seemed like a massive amount of real estate, bore dated handwritten labels whose descriptions varied from the subdued to the enthusiastic. “Play until the needle goes through the vinyl” on Ministry’s The Mind is a Terrible Thing to Taste is a good example of the latter.

There was no list of approved bands; DJs could play any music they wanted, as long as it was “alternative music,” defined as almost anything that wasn’t on commercial radio or MTV. I’m not sure who devised these guidelines, but DJs generally treated them as Gospel. There was another important rule: 25% of one’s playlist had to contain music that had been released during the past three months. But the number of CDs and records that we received from music labels made complying with that rule fairly painless.

Some of my listeners were quite devoted and knowledgeable; others defied easy categorization. Take, for example, the No-Penis Guy, a gentleman who would occasionally ring the station to request a track by the Bloody Stools and also to inform the on-air DJ that, for undisclosed reasons, his (presumably-irate) girlfriend had removed a good portion of his member with her teeth. The caller would then offer unsolicited assurance that the remainder of his organ could still adequately perform at least one of its intended functions; “I can still get chicks off with it,” as he put it. I was not the sole recipient of this dude’s late-night calls; a former fellow DJ recently confirmed my memories of No-Penis Guy’s general MO; for the curious, neither of us ever learned the gentleman’s identity.

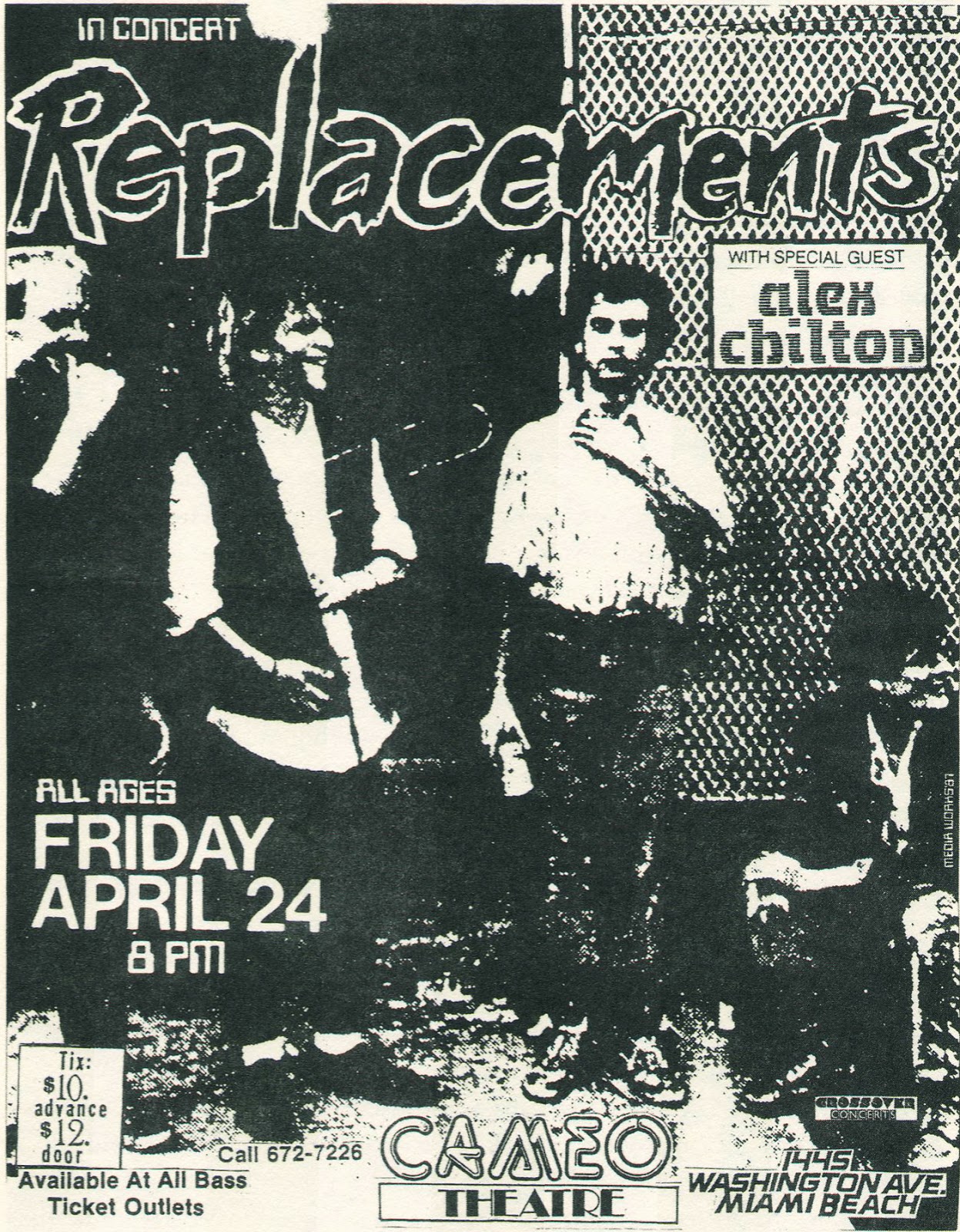

During the 1980s and 1990s, music aficionados were frequently confined to the offerings of commercial radio and, if one had cable, MTV and VH1. College radio played material largely unavailable elsewhere, a bright spot in an otherwise-bleak musical landscape. Readers can surely list a slew of bands who became known via college radio. There were precious few other ways to learn about new music and, even if one had reasonable access to decent music stores and informative music publications, still fewer ways to hear it before purchase. Word-of-mouth, tape trading, and live shows were obviously great, but many music enthusiasts lacked access to those sources. These days, of course, there are many more outlets by which fans can discover and consume music.

So, what function does college radio serve these days?

Searching for an answer, I discussed this topic with past and present college radio DJs, music industry experts, and musicians.

Nearly everyone with whom I spoke with for this article confirmed that my recollections about college radio’s value are not mere nostalgia. Brian Lowit, label manager at Dischord Records, agreed that college radio “had a huge reach” and “was one of the few ways you could hear new music;” he described 1980s- and 1990s-era college DJs as “tastemakers.” Megaforce Records, whose roster included Anthrax, Metallica, Overkill, and Testament, valued the medium enough to create the first “college radio metal marketing team,” according to the label’s co-founder Jon Zazula, who added that such an effort “wasn’t even a dream for other labels.” Echoing these sentiments, Anthrax drummer Charlie Benante told me that college radio “supported us so much back in the day and were responsible for breaking a lot of bands.” Artists “would give college stations their new record and they would be the first to play it for people,” he added.

At first glance, the current proliferation of avenues for discovering, hearing, purchasing and distributing music might seem to obviate college radio’s role as a bridge between artists and listeners. Indeed, some colleges have sold their stations’ broadcast licenses in recent years; Pitchfork reported in 2017 that, “starting around 2010, a growing number of colleges began transferring their FM broadcast licenses to larger conglomerates for a short-term economic windfall.” Georgia State University, Rice University, the University of San Francisco, and Vanderbilt University are among such institutions. On top of that, the widely-read and hugely important College Music Journal (CMJ) stopped publishing its charts around 2017.

Perhaps college radio has peaked in some sense, there is simply too much competition for the situation to be otherwise. Yet, students and community members continue to play music on college radio, which broadcast over the airwaves and stream online. “College radio listenership is still made up of real music fans,” according to Zach Wild of The North American College & Community Chart (NACC), which became the chart of record after CMJ stopped and now aggregates about 800 of them per week. The format’s DJs are “early tastemakers and influencers” who “champion music that they love,” he added. Sub Pop Records radio promotions manager Michelle Feghali similarly argued that “if you want to hear new music, college and non-commercial radio is always the way to go.”

While writing this article I heard widespread agreement that college radio is a valuable guide in a music landscape saturated with content. Describing college radio as a “trusted source,” KUTX program director Matt Reilly explained that the role of this listener-support station in Austin is “to curate the firehouse” of available music. Many longtime fans retain an interest in music, but, according to him, “don’t have the bandwidth” for discovering material via other avenues.

Of course, a number of online music sources suggest music for listeners, but those features have limits. “Algorithms don’t have taste,” DJ Semantichrist, a 31-year veteran of college and community radio, succinctly observed.

Anthrax’s Benante argued that “the DJ is a very vital thing that we’re missing nowadays. You know, we just hear song after song. But, you know, a DJ will tell you that this is happening. This band is doing this.” Katherine Patton, Programming Director of Seton Hall’s WSOU agreed, noting that “the human factor is so important, especially in a [relatively-obscure] genre where you won’t find the next big thing” on a streaming service. WSOU’s Promotions Director Valentino Petrarcca added that, in his view “algorithms will never be as successful as human DJs” because “we are social animals” and, therefore, “the human voice is so much more powerful than a machine’s recommendations.”

The human factor’s importance was a recurring theme among interviewees. Joe McGinnis, Senior Director of Radio Promotion for The Syndicate marketing agency pointed out that a DJ can give listeners context for a song, such as its place in the artist’s catalog. Stations such as Tufts University’s WMFO give audience members a connection with a DJ’s music tastes. Zoe McKeown, that station’s publicity director, explained to me that whatever music WMFO broadcasts “is entirely the choice of the DJ.” Amanda Roussel, Publicity Director for Boston College’s WZBC, opined that there is “something more human” about discovering music from an actual person. For its part, KUTX saw a considerable increase in its listenership after the DJs returned to broadcasting following a 7-week Coronavirus-induced hiatus, according to Matt Reilly, who explained that the station “heard from audience members that they were happy that the hosts were back.”

But there is a generational gap when it comes to college radio. Diamond Rowe, guitarist for L.A.-based heavy metal band Tetrarch, explained that the band, whose first full-length album debuted in 2017, hadn’t first considered college radio as a vehicle for promoting their music, although the band has since received positive attention via the medium. And WMFO’s McKeown noted that prospective student DJs are often more attracted to college radio by the opportunity for social interaction than for music discovery.

For its part, the music industry still values college radio, although the extent to which music labels interact with stations varies. Lowit of Dischord Records described the label’s interactions as “pretty limited these days,” adding that music distributors “don’t even ask [the label] about college radio.” However, NACC’s Zach noted that “a fair amount of labels and promoters are communicating directly with stations,” explaining that, given the vast amount of music currently distributed, stations’ program directors “also rely on promoters and labels to be tastemakers themselves.” Sub Pop’s Feghali emphasized that the label makes a particular effort to give college and noncommercial stations “as much music as we can” and explained that college DJs help her stay current on “what is interesting in the college community.” Feghali also noted that she frequently communicates with music and program directors because “they’ll be the ones who will have a say in the music industry in five to ten years.”

Some musicians continue to mine college radio’s potential; a number of DJs confirmed that artists sometimes contact stations directly to promote their own self-produced music. McGinnis of The Syndicate characterized the medium as a place for artists to make a “tangible presence not driven by record sales.” Pointing out one of the medium’s advantages, Tetrarch’s Diamond Rowe mused that college radio listeners “probably really want to hear about new music,” a sentiment echoed by several other interviewees.

In a world saturated with music outlets, noncommercial radio retains unique characteristics which help artists and fans to cut through the noise. Characterizing DJs as “the human algorithm,” longtime WRUV DJ Melo Grant recounted that she was described by a high-school student as “better than Spotify!” Many college DJs seem worthy of that title, which is one reason why the medium retains value.

WSOU’s Patton told me that her enthusiasm for Melted Bodies motivates her to play their music and inform her audience about the band. This same passion for the medium was evident among the people who generously took the time to speak with me for this article. College radio isn’t obligated to play any particular artist or deliver exactly what any particular listener wants to hear at a given moment. But those are good reasons to tune in. One imagines that college DJs are still amassing memorabilia, playing obscure artists, and receiving (hopefully less-obscene) phone calls from misguided listeners.