The Button-Pushing Impresario of Balenciaga

A bare white room, smelling of nothing. Nervous coughs going around like the wave. It was eleven-thirty on a Sunday morning in March—the Mass hour, Balenciaga’s traditional slot on the Paris Fashion Week calendar—and editors, buyers, clients, and the odd quidnunc had gathered at the Carrousel du Louvre, a cavernous mall under the museum, to attend the presentation of the house’s Fall 2023 collection. The Business of Fashion was calling it Balenciaga’s “make-or-break” moment; the Times, “the single most fraught show of the season.” The brand was trying to recover from a pair of botched ad campaigns that, in December, had led to a wild farrago of accusations, including that it had sexualized children and condoned child abuse. On each seat sat a white card bearing a message from Demna, the brand’s artistic director. “In the last couple of months, I needed to seek shelter for my love affair with fashion,” he wrote, explaining that he’d found solace in darts and notches, shoulder lines and armholes. He concluded, “This is why fashion to me can no longer be seen as an entertainment, but rather as the art of making clothes.”

Until now, Demna had been the industry’s greatest impresario. If fashion was entertainment, he was its P. T. Barnum and its Walter Benjamin, possessing a simultaneous talent for leading the spectacle and subjecting it to critique. The house of Balenciaga was founded by Cristóbal Balenciaga in 1937. Demna joined the company in 2015 and, with Cédric Charbit, the C.E.O., grew an estimated three-hundred-and-fifty-million-dollar business into a two-billion-dollar megabrand, with witty hit products such as a “Bern-lenciaga” sweatshirt, with the Balenciaga name in the style of a political-campaign logo, and platform clogs produced in collaboration with Crocs and known affectionately as “the ugliest shoe ever made.” In 2022, Time named Demna one of the hundred most influential people. His work impressed critics as much as it delighted the masses. “He essentially knocked the craft into a new orbit,” Cathy Horyn wrote in the Cut last year, when he brought haute couture back to the house after a half-century hiatus. You have been dressed by Demna, at least indirectly, if you’ve recently worn a clunky sneaker or a humongous coat.

Like his designs, Demna’s shows were big, weird, intense, and somehow intelligent in proportion to their shock value. They were full of humor, too. He once sent lanyard-wearing models traipsing around a blue-carpeted chamber that recalled the European Parliament. Another time, they navigated the trading floor of the New York Stock Exchange in latex bodysuits, leaving the audience to decide whether the ultimate fetish was money or sex. Mid-pandemic, while competing brands churned out pretentious short films, Demna revealed a collection on the online game Afterworld: The Age of Tomorrow. Later, he persuaded the creators of “The Simpsons” to collaborate on a ten-minute short in which Homer realizes that it’s almost Marge’s birthday. “Dear Balun . . . Balloon . . . Baleen . . . Balenciaga-ga, I’m in a jam and need some help,” he writes.

“Demna’s the only one who talks about the things we’re all thinking about,” Alexandra Van Houtte, the founder and C.E.O. of the fashion search engine Tagwalk, told me. In his Winter 2020 show, floodwaters rose over the runway as starlings murmurated on a screen overhead, braving fire, thunder, and crashing waves. Two years later, days after the start of the war in Ukraine, Demna, who was born in Georgia in 1981, draped each chair in a blue-and-yellow T-shirt. (He dropped his last name, Gvasalia, in 2021, because he wanted to separate his personal life from his professional life and because people kept mispronouncing it.) The show featured a band of stoic, lonely figures in a dystopian arena of howling wind and driving snow. If brands like Dolce & Gabbana evoked an endless summer, Balenciaga was eternal winter, maybe nuclear. “I read the news,” Demna told me. “I can’t disconnect from reality and just, you know, live inside my office space.” Other designers take us to the Qing dynasty or the Belle Époque, to Djuna Barnes’s Left Bank flat or Talitha Getty’s Marrakesh villa. Demna had been willing to take us there, to the juncture of a violent world and the clothes that might make us feel better while hastening its collapse.

His “mud show,” in October, 2022, will probably go down in fashion history as the apogee of the spectacular style of fashiontainment that he was now swearing off. The invitation came in the form of a battered wallet, stuffed with the personal effects of an Everywoman character named Natalia Antunes. They included her gym membership card, her government I.D., receipts from a vegan supermarket. The change purse was even filled with fake coins. The banality of the items offered an amusing counterpoint to luxury fashion’s ever-escalating swag wars. The invitation announced that the show would be held at a convention center in the suburbs of Paris, a very you-come-to-us venue that did nothing to discourage a caravan of livery cars.

This was my first foray into the Balenciaga universe. I was taken with the crowds of fans hanging around the parking lot, diverse in identity but unanimously committed to bladelike sunglasses, bulbous boots, and hulking outerwear in Balenciaga’s famously absolute shade of black. (Harper’s Bazaar described it in 1938 as “thick Spanish black, almost velvety, a night without stars, which makes the ordinary black seem almost grey.”) The audience was hard to distinguish from the brand’s employees, who were hard to separate from the bouncers, whose uniforms Demna has drawn upon in popularizing the goons-in-coats look. Whatever detractors might say about Demna’s aesthetic—“trashy,” “hideous,” “gotdamn ridiculous”—it was authoritative. Next to Balenciaga, everything else looked uncool.

Inside, it stank. This was the effect of two hundred and seventy-five cubic metres of mud, excavated from a peat bog, that the artist Santiago Sierra had used to construct an elliptical pit. Guests found their shoes and bags splattered as they groped toward their seats in the dark. Then the music began: electronic, discordant, throbbing. (Demna’s husband, Loïck Gomez, a musician known as BFRND, creates the soundtracks for all of Balenciaga’s shows.) The models filed out, circling the dirt track like gladiators. They had artificial cuts on their foreheads or spiky prosthetics protruding from their cheeks. Others wore mouth guards that swelled their lips as though they’d just been punched in the face.

The most memorable looks were the most demotic: shrunken puffers, blasted-out jeans, a leather gown spliced from old handbags, a series of hooded sweatshirts paired with tap pants so paltry that you could almost feel the goosebumps on the models’ scraggy legs. The models were not all traditionally perfect-looking, and a number were over thirty. One, a Finnish model named Minttu Vesala, carried themself with a bowed, aggressive gait that launched a TikTok parody trend known as the “Balenciaga walk.” Male models schlepped lifelike dolls in chest carriers: Balenciaga in the back, BabyBjörn in the front. Totes featured sleeves that you stuck your whole arm through, fusing bag and self. “The set of this show is a metaphor for digging for truth and being down to earth,” Demna wrote.

For Penny Martin, the editor-in-chief of The Gentlewoman, the show signified “how quickly anything cool is extracted from the underground and injected into mass culture.” One commentator praised the show’s “Nosferatu Modernism,” while others likened it to the scene in “Zoolander” in which the poodle-tressed designer Jacobim Mugatu launches a collection called Derelicte, inspired by “the very homeless, the vagrants, the crack whores that make this wonderful city so unique.” For days after, my hair and my clothes reeked of peat bog. (Balenciaga had commissioned the scent artist Sissel Tolaas to augment the mud’s natural odor.) This was annoying but kind of brilliant. I read it as a commentary on the fashion-industrial complex, tainting anyone who partook.

The quiet scene at the Carrousel du Louvre was a departure from the showy worlds that Demna had excelled at building. Balenciaga had asked attendees not to disclose the show’s location. In December, as the ad-campaign drama escalated, Demna had hunkered down in Zurich, where he lived until recently. He got out his sewing machine, he told reporters, and started experimenting with a stack of pants, calming his mind by busying his hands.

In our conversations before the show, Demna had expressed a subdued optimism. He saw the ad controversy as a catalyst for a change of speed but not of direction, “accelerating my evolution for the house by maybe three or four years.” He explained that he had enjoyed igniting debates, but that the provocateur role had already begun to feel tired. “Then, from the end of last year, with everything we went through, I just woke up one morning and said, You know what, I don’t need to wait another year or two to mature as a designer,” he said. Now he was promising armholes, not sinkholes; craft, not Crocs. This was expedient, but also seemed to correspond to a genuine sense that the theatrics had started to overwhelm his work. At the mud show, you could hardly see the clothes. Demna later told a reporter that he “felt like shit” afterward.

The invitation to the Carrousel du Louvre show was a jacket pattern. You could supposedly take it to your tailor and have a Balenciaga blazer of your own. The runway was lined with ecru muslin, which fashion houses use to make prototypes. The implication was one of relative humility. No more memebait, like an eighteen-hundred-dollar calfskin sack that resembled a Hefty garbage bag, which Demna sent down the runway in 2022, saying, “I couldn’t miss an opportunity to make the most expensive trash bag in the world, because who doesn’t love a fashion scandal?” Now he was promising a move toward the basics, a fresh start on plain cotton. He told me, “I realized I don’t like being a fashion designer at all. In some other life, I was probably a seamstress.”

The music began, an austere medley of piano and guitar. First out was Eliza Douglas, a rangy, cerebral American painter who has been described as Demna’s muse. She wore a black double-breasted suit with her usual lank hair and wire-rimmed glasses. The sleeves ran past her fingertips, as is Demna’s wont. He had added long flaps to the trousers, which blurred the line between pant and skirt, swishing like a liturgical vestment as Douglas walked. More trompe-l’oeil tailoring followed—on one trench, an upside-down waistband formed the yoke. The closest Demna came to cheekiness was inflating a set of motorcycle jackets and hoodies using technology designed to keep athletes from getting injured. The engorged garments were cartoonish, humping backs and deleting necks, but they were grounded in Balenciaga’s house tradition of the voluminous silhouette. They also acknowledged vulnerability, offering protection against a world that could knock you around. (The absence of conspicuous branding accomplished this in a different manner.) A group of evening gowns, which closed the show, were uncomplicatedly gorgeous, with convex, ski-mogul shoulders.

Backstage, Demna seemed relieved. “I wanted it to be over before it even began!” he told me, wiping his brow. The show wasn’t uninhibited, or groundbreaking, but it confirmed that he could compete purely on technical prowess. “Demna did exactly what he said he was going to do,” Miren Arzalluz, the director of the Palais Galliera fashion museum, said. “He gave us the chance to concentrate on the garments.” The next day’s reviews affirmed that, for the fashion press, he remained viable in his job. The consensus was that he had played it safe, but there were hints of audacity in the presentation. In a way, he was defending his ideas and his integrity, using the same models, archetypal silhouettes, familiar prints. To reset his career, he had chosen continuity.

In the verdant yard of the “modern farmhouse” in Scottsdale, Arizona, that they share with their three children—Alessi (three) and Senna and Lux (twenty-one-month-old twins)—Arie Luyendyk, Jr., and Lauren Luyendyk filmed themselves setting fire to a pair of sneakers with a blowtorch. A popular version of Balenciaga’s best-selling Speed line of “tech-knit hybrid leisure sneakers,” which retail for more than nine hundred dollars, the shoes were sleek and white, with a sinuous foam sole. They hugged the foot like a tube sock, or a scuba boot, and were said to make wearers feel like they were walking on marshmallows.

Lauren Luyendyk held the flaming sneakers with a pair of grilling tongs as her husband doused them with accelerant. Then she dropped them into a large bin with a flick of the wrist, as though disposing of a dead rat. In a video that the couple posted on Instagram on December 1st, a manicured hand flashes a peace sign over the smoldering trash-can fire. “Bye, Balenciaga,” a woman’s voice says. One commenter applauded the couple for “taking a genuine stand against the true evil in this world.”

Previously, the Luyendyks had been noted less for their moral leadership than for having appeared on the twenty-second season of “The Bachelor,” in which Arie licked a bowling ball, said that the thing that most excited him was “excitement,” and asked another woman to marry him before dumping her on prime-time television and proposing to Lauren. The couple was angry about the ad campaigns, which Balenciaga had released weeks earlier. The first campaign, which went live on November 16th, was for Gift Shop, an assortment of holiday items. To shoot it, Balenciaga had hired Gabriele Galimberti, an accomplished documentary photographer. Galimberti is known for projects such as “Toy Stories,” which depicts children from fifty-eight countries surrounded by cherished bulldozers, building blocks, and stegosauruses. The Gift Shop ads featured kids displaying collections, but their personal playthings were replaced with Balenciaga merchandise.

Whereas the intimacy of Galimberti’s approach made sense in a documentary context, the sight of young children in fake bedrooms, surrounded by adult accessories, felt weird. In one picture, a girl stands alone in front of an open window, clutching a bag that consists of a Teddy bear clad in a leather harness, surrounded by rows of stuff: Balenciaga jewelry, Balenciaga coasters, a Balenciaga dog bowl, Balenciaga wineglasses and champagne flutes, Balenciaga candles stuck into mock Balenciaga beer cans. In another, an unsmiling child model dressed in black totes another version of the Teddy, with a padlock around its neck and a fish-net shirt. The over-all atmosphere is unsettling and even a little louche, but the images didn’t provoke immediate mass outrage. “Balenciaga launched an objects line and it’s an absolute need,” a life-style site proclaimed. “We’ll take one of everything.”

On November 21st, the company unveiled a separate campaign, promoting Garde-Robe, a line of luxury basics. The ads featured celebrities such as Bella Hadid and Nicole Kidman posing in glass-encased executive offices. In one image, a black leather handbag sits on a messy desk atop a pile of printouts and manila folders. Zooming in on the documents, Internet sleuths identified a page from the United States Supreme Court’s ruling in U.S. v. Williams, a 2008 case in which the plaintiff, invoking First Amendment protections, unsuccessfully argued for the reversal of a child-pornography conviction. The Twitter account @shoeØnhead, run by June Nicole Lapine, a controversial YouTuber, posted about the “very purposely poorly hidden court document about ‘virtual child porn.’ ” Further scrutiny of the pictures’ office décor turned up a book by a Belgian artist who once painted small, naked children covered with blood. In another image, a college certificate bore the name John Phillip Fisher, which viewers connected with a 2018 news article about a Michigan man of the same name who was charged with molesting his granddaughter.

Never mind the hundreds of blameless John Phillip Fishers, leading bioengineering departments or working in agriculture. Never mind that the logic of the accusations didn’t really cohere—U.S. v. Williams found against child pornographers, not for them. For the conspiracy-minded, proximity to child-pornography-themed jurisprudence in one campaign, taken with the images of children in the other campaign, was enough to damn Balenciaga. “They’re getting sloppier about their underworld,” one Twitter commenter declared, adding vomit emojis for emphasis. Other social-media users sniffed out what they believed to be hidden references to the Illuminati, the Rapture, and Satanism.

Soon, Tucker Carlson picked up the story on Fox News, introducing Balenciaga as a “so-called luxury brand” that sold “cotton sweatshirts for fifteen hundred bucks” and had just launched an abhorrent publicity campaign. “The selling point of the ads is sex with children,” Carlson claimed. You could look at the pictures and see a fashion brand trying too hard to be edgy, or you could see, as Carlson did, a decadent left-wing pedophile cult linked to everything from the Jeffrey Epstein scandal to “the fact that doctors are cutting the breasts off of healthy teen-age girls.” Invoking a larger American culture war over gender politics, the media attention activated practiced polemicists such as Brittany Aldean, a Trump-supporting, trans-skeptic makeup artist who is married to the country singer Jason Aldean. For her Balenciaga purge, Aldean was photographed on the loggia of her Nashville mansion, carrying transparent plastic bags filled with the brand’s wares. “It’s trash day,” she proclaimed.

In the past, Demna had responded to criticism head on. Called out for the overwhelming whiteness of models at Balenciaga and at Vetements, the brand that he founded before starting his current job, he diversified his casting. When critics accused him of ripping off the designer Martin Margiela, he produced a Margiela-inspired collection entitled The Elephant in the Room. This time, he was slow to react. An early apology, in which Balenciaga threatened legal action against “the parties responsible for creating the set and including unapproved items,” only stoked the controversy. (Balenciaga eventually dropped a twenty-five-million-dollar lawsuit.)

In London, someone decorated the front window of a Balenciaga boutique with a “PAEDOPHILIA” decal. In Beverly Hills, vandals tagged a store with stick figures of victimized children. Admirers who, weeks before, couldn’t stop talking about Demna’s genius were nowhere to be found. At one point, the fashion critic and writer Sophie Fontanel told me, Demna had received just two calls—“from Anna Wintour and from me.” Kim Kardashian—a brand ambassador and a Balenciaga-head of such proportions that she once attended a show with her entire body wrapped in bright-yellow Balenciaga-branded packing tape—announced that she was “re-evaluating” her relationship with the house. Imran Amed, the founder and C.E.O. of The Business of Fashion, told me that the only commensurate scandals he could recall, in terms of “crisis heat,” were John Galliano’s antisemitic outburst of 2011 and Dolce & Gabbana’s offensive foray into China in 2018.

The uproar was unprecedented, but it didn’t come entirely out of nowhere. For years, Balenciaga had built its reputation on provocation. “The trash bag was really a big red button that said ‘Don’t push,’ ” Demna said, early last year. “That’s exactly why I did it! Because I hate prohibitions.” Many people assumed that the ads were intentionally outrageous, the latest entries in the long annals of stupid fashion stunts. (Remember Calvin Klein’s suggestive rec-room ads, which caused the Justice Department to investigate the brand for child pornography, and Tom Ford’s Gucci-branded pubic hair?)

Even for a brand that delighted in testing limits, Balenciaga had spent the months leading up to the ad controversy on the edge between fearlessness and foolishness. To open the mud show, Demna had chosen an unconventional model: his friend Ye, once known as Kanye West, who came clomping down the runway in a gargantuan-shouldered paramilitary look. Ye had been one of Demna’s earliest and most fervent supporters from his Vetements days. Just after Demna’s appointment by Kering, Balenciaga’s parent company, Ye tweeted, “I’m going to steal Demna from Balenciaga,” sending his reputation soaring. Ye became one of the brand’s major clients, spending more than four million dollars in the course of twelve months in 2021 and 2022, according to a screenshot of his customer account that he posted on Instagram. The men got to know each other and began a heady running dialogue that Demna once described, to the Times, as a “very intense creative exchange.” Demna consulted on Ye’s projects. Ye reportedly called himself Demna’s “straight husband.” One after the other, they announced their desire to be known by mononyms.

Less than forty-eight hours after opening the mud show, Ye presented his own Yeezy Season 9 collection, appearing in a shirt that said “WHITE LIVES MATTER.” Demna and Cédric Charbit, Balenciaga’s C.E.O., were in attendance. As others distanced themselves from Ye, Balenciaga remained silent about the incident. The company also said nothing when, days later, Ye posted a series of antisemitic comments. Only after Ye claimed on a podcast that George Floyd had died of a fentanyl overdose, and that “the Jewish media” was out to get him, did Balenciaga publicly back away, stating that the brand “has no longer any relationship nor any plans for future projects related to this artist.” The situation exposed the riskiness of Demna’s gravitation toward the most volatile parts of pop culture. It also suggested that the brand was losing focus. “I think they just got a little too cool for school,” one fashion executive told me. “They went away from the clothing.”

The advertising controversy, then, was one big red button too many. For years, Balenciaga had hovered near the top of the Lyst Index, a quarterly ranking of fashion brands’ desirability. In the third quarter of 2022, the brand was the fourth hottest in the industry. Following the ad scandal, it dropped out of the top ten for the first time since 2017. In February, Kering released its latest earnings report, noting that Balenciaga had had a “difficult month of December.” Kering does not disclose individual results for Balenciaga, classing it with a handful of other brands, which collectively experienced a four-per-cent drop in revenues in the fourth quarter. On an earnings call, François-Henri Pinault, Kering’s chairman and C.E.O., said that he regretted “a clear error of judgment.” Defending Demna and Charbit, he said, “We believe people have the right to make mistakes—that’s important to us at Kering. Just don’t make them twice.”

Demna and Balenciaga have apologized repeatedly for the ad campaigns. The brand has announced a three-year partnership with the National Children’s Alliance. (Charbit described the commitment as a “multimillion donation” but declined to provide a specific number, saying that he didn’t want to give the impression that the brand was trying to buy its way out of trouble.) Balenciaga put forth a straightforward explanation for the odd items strewn around the Garde-Robe campaign: they were random papers, furnished by a prop-rental company, and any connection to child pornography or child abuse was unintentional and purely coincidental. (The brand has nonetheless acknowledged that it should have examined the setup more closely.) I saw a copy of an investigation that the company commissioned—its version of a January 6th report. A section on the Garde-Robe campaign could venture only a bewildered guess at the origin of the décor: it “could have been from ‘Law & Order.’ ”

In an interview with Vogue, Demna explained that the Teddy-bear bags in the Gift Shop ads were meant to reference “punk and DIY culture, absolutely not BDSM.” Still, he admitted that the campaign was ill-conceived. “I didn’t realize how inappropriate it would be to put these objects [in the image] and still have the kid in the middle,” he said. “It unfortunately was the wrong idea and a bad decision from me.”

I asked Demna what the intended message had been. “There was no message—it was more a solution,” he said. He explained that Galimberti had been on a list of photographers he wanted to work with and that the project had seemed like a good fit, for practical reasons, since there were so many products to advertise. “For me, it was really about the composition, and the fact that we could put all these items in one image,” he said.

According to the internal report, a committee of dozens of people approved the campaign before it went out. Only one of them raised a concern, sending an e-mail that wondered whether “the juxtaposition of a little child and all the black and bats and stuff just seems a bit sinister,” but the bear bags didn’t come up for discussion.

“I didn’t see the creepy part of it,” Demna told me. “But it’s obvious now. In French, we say, ‘Je pense tellement pas au mal que je vois pas le mal.’ ” (“I’m so not thinking about harm that I don’t see the harm.”) He continued, “That’s why I call it a stupid mistake.”

The supposed darklord of luxury fashion is a forty-one-year-old teetotalling vegetarian who lives in fondue country with his husband and their two Chihuahuas, Cookie and Chiquita. He speaks seven languages (Georgian, German, Flemish, English, French, Italian, Russian), swears by Brené Brown (her podcast recently taught him to name the emotions “anguish” and “awe”), and begins his mornings doing guided meditation with the Serenity app. (The dogs jump on him the second he takes off his headphones.) Other than making clothes, what he likes doing most is cooking. His specialty is khinkali made with plant-based beef that even his parents—who were constantly telling him as a kid that he had to eat meat to be a man—admit is O.K. He is a warm conversationalist, but describes himself as a loner, even “a loser.” (“I do have maybe two friends,” he said.) He maintains no public presence on social media. Using a finsta, he follows “eccentric old ladies” and “weird European maps.”

Demna was born in the Soviet Union, “that immense now nonexistent country,” he once wrote. His father, Guram, is Georgian. He was a car mechanic and a hot-rod enthusiast. His mother, Elvira, is Russian. She was a housewife. They raised Demna and his younger brother, also named Guram, in Sukhumi, a resort town on the Black Sea. Privacy, solitude, and individual possessions were scarce commodities in their home, a three-house compound that they shared with a gaggle of relatives—paternal grandmother, uncles, cousins. What was theirs was Demna’s and what was Demna’s was theirs. Demna has joked that the best-dressed member of the family was whoever got up first in the morning. He remembers the smell of ink-jet printers and glue—his tinkerer-hustler dad, in the garage, whipping up D.I.Y. American-style T-shirts and sneakers to sell on the black market. “Obviously, you had to use elements from that part of the world,” Demna said. “So instead of, like, Mickey Mouse, they would do a Russian version of it.”

Demna’s first object of desire was a tape measure. He wanted to cross-stitch. His parents wanted him to go outside and play soccer. As soon as he could write, he composed a letter to them, he recalled, “in which I told them that they don’t understand me and they don’t really love me and they don’t know who I am.” He is still a little sad about the way they responded to the letter. “They found it cute,” he said. “And everybody laughed, and they would show it to their friends, like, ‘Oh, look at this. Of course we love Demna. He doesn’t see.’ But it was not a very mature response. I think I had much deeper issues, and I was going through a lot of pain.” He added, “It would have helped me a lot in my adult life if they reacted differently.”

At school, Demna shortened his trousers so that his socks would show. The principal accused his parents of propagating capitalist values. As a member of the Young Pioneers, he had to wear a red neckerchief. This irked him: the conformity, the dorkiness. In his “first conceptually active act of fashion vandalism,” he scribbled lyrics from the Soviet rock band Kino’s “Blood Type” on the fabric in black marker. (“My blood type, on my sleeve / My service number, on my sleeve / Wish me luck in battle!”) The fall of the Soviet Union brought a confusion of stimuli. It was hard to tell fact from fiction, the alluring from the contemptible. Demna once told a magazine, “I remember seeing a Coke can for the first time and thinking it was a nuclear bomb.”

In 1992, Abkhaz separatists, backed by Russia, attacked Sukhumi. Demna, who was ten years old, spent most evenings huddling with his family in a neighbor’s cellar. Eventually, a bomb hit the family’s house, burning it to the ground. During a pogrom targeting ethnic Georgians in the fall of 1993, the family fled. Demna was racked by fear that they would be captured and tortured, or that his father would kill them rather than submit. They travelled nearly three hundred miles along the Caucasus Mountains—going as far as they could on foot, then waiting a week for a crowded helicopter. They finally made it to Tbilisi, where they settled.

Demna wrote in the notes to his Winter 2022 show that the conflict in Ukraine had “triggered the pain of a past trauma I have carried in me since 1993.” The show began with Demna sombrely reading a poem by the Ukrainian writer Oleksandr Oles. The models, dragging their belongings, made their way through a snowstorm—accompanied by melancholy piano music and then pounding techno—never flinching as the conditions around them deteriorated. Demna had started planning the presentation months before the war began, but as a Ukraine diorama it was eerily on the mark. With Kim Kardashian, A$AP Ferg, and a Mrs. Doubtfire impersonator in attendance, the show suggested that luxury wasn’t going to save anybody. It was heart-seizingly beautiful, down to the final gown’s cerulean, wind-whipped train. “We live in a terrifying world, and fashion is a reflection of that,” Demna once said. “If it triggers that fear or terror, then I’ve succeeded.”

In Tbilisi, Demna wore hand-me-downs and castoffs. His parents economized by buying him clothes that would fit for several years. The oversized look suited him, anyway, as it hid the hair that started growing on his hands in adolescence. He still mostly wears T-shirts and sweatshirts, leaving the sleeves too long, in homage to his earliest stirrings of self-expression and self-defense.

Rarely has anyone explored so deeply the protective aspects of fashion—Demna’s clothing can be scary, but it can also be scared. The strains in his work that some people interpret as cynical are often aching and personal. He is one of the photographer Cecil Beaton’s fashion individualists, capable of imbuing “a stepladder or a wicker basket” with significance. His work makes a case that Tbilisi, Georgia—or wherever—can be more meaningful to the creative imagination than Talitha Getty.

Demna and his family moved to Düsseldorf when he was twenty-one. He has not been back to Georgia since, even though he says that he feels deeply connected to Georgian culture, which he often incorporates into his work. Vetements’ Spring 2019 collection tackled his complex emotions about “family and war.” A plain white shirt was covered with signatures and scribbles, recalling a high-school-graduation tradition in Georgia. A form-fitting tunic, the color of beige flesh, was overlaid with the sort of tattoos favored by post-Soviet gangsters. Each piece in the collection featured a QR code that, when scanned, led customers to the Wikipedia entry for “Ethnic cleansing of Georgians in Abkhazia.” Demna doesn’t feel safe as a gay man in Georgia, where some of his family members consider him a disgrace because of his sexuality. Last year, when the mayor of Tbilisi named him an honorary citizen, a deacon of the Orthodox Church condemned the award, denouncing “the self-declared sodomite Demna Gvasalia.”

In Düsseldorf, the Gvasalias spent three months in a camp for immigrants. Demna already spoke German, so he acted as the family’s go-between. The experience of navigating a “hard-core” bureaucracy compounded his interest in “sociological uniforms”—the jackets, caps, armbands, boots, badges, and patches that people use to signal to their peers who is in control. The fascination perhaps began with his grandfather, a pilot with Aeroflot, and his grandmother, an airport secretary. “They really had this airport life,” he recalled. Vogue once called Demna “the CCTV of fashion, or perhaps its all-seeing drone.” He admires the ready-mades of Marcel Duchamp, but there is a keen-eyed side to him that recalls the photography of August Sander, taxonomizing the daily parade. Some people were confused by an oblong pocket that Demna added to the interiors of coats, until he explained that they were a nod to partygoers he’d seen around town, fumbling to open a door while holding a bottle of wine.

By the time the Gvasalias arrived in Düsseldorf, Demna had already earned a degree in international economics from Tbilisi State University. His parents were thrilled by the possibility that he could get a job at a German bank. Demna had been told that fashion was a career for rich girls; he was a poor boy. But “the day I got my B.A. degree in economics, I knew I would never work as an economist in my life,” he once wrote. “The only thing I wanted to do was making clothes and using fashion as a tool to discover and build my own identity.”

Demna applied to the fashion school at the Royal Academy of Fine Arts in Antwerp, a famously demanding program that was comparatively inexpensive. At his admission interview, someone asked him his favorite designer, and he said Dries Van Noten, because he’d just seen the name in a shopwindow. Fortunately, Van Noten was a member of the Antwerp Six, a group of pioneering designers who came out of the school in the nineteen-eighties. Demna was in. “He was a good student, but not really one that you say, ‘Wow, that one!’ ” Linda Loppa, who was the head of the school for many years, told me. “He became that later, because he had an open mentality, he was curious, and he was humble.”

Students were supposed to start from sketches, but Demna worked more naturally in three dimensions, draping fabric on the body. He cared about the clothes, not their putative inspiration. Demna recalls fashion school as a formative period of “breaking needles of my cheap sewing machine from Lidl, drinking cheap red wine, chain-smoking and listening to loud music.” In his second year, he secretly entered a talent contest in Trieste, winning first prize on the strength of a collection of tailored menswear. Demna remains close with many of his classmates and teachers. When he designed Balenciaga’s fifty-first haute-couture collection, he gave his former drawing teacher Yvonne Dekock a black plissé dress modelled on one that he remembered her wearing during his student years. “He said, ‘Now you’re like before, like when I saw you in school,’ ” Dekock recalled.

After working for two years with his former professor Walter Van Beirendonck, of the Antwerp Six, Demna applied to Martin Margiela, the eponymous house founded by the Royal Academy’s most famous graduate. Since the house’s inception, in 1988, Margiela had been known for an avant-garde mentality, paired with classical technique. Martin Margiela, the man, had recently retired, and the future of the brand was unclear. Demna decided to submit his portfolio. He told the magazine System, “Maybe it was my economics mind, but I thought, ‘They need to open it, they need to look at it,’ because I know often in companies they get things they don’t even bother to open. I thought the packaging was important, so I put it in a pizza box from a restaurant called Don Giovanni. The CEO was called Giovanni, too. That got their attention—and it was not a fresh pizza box! I was, like, ‘Let’s just go for it.’ ”

A gimmick can be a mark of sincerity—a willingness to put oneself on the line. Demna got the job, as a member of Margiela’s design studio. He was passionate about Margiela’s legacy, but management wanted to take the brand in a new direction. “They just didn’t see the value of the right thing, unfortunately,” he said. “I couldn’t convince anyone, because I had no authority at all.”

In 2012, Demna signed on at Louis Vuitton to work as a senior designer of women’s ready-to-wear collections under Marc Jacobs. The designer Julie de Libran, Demna’s boss there, remembered him as talented, mature, and “super introverted.” She said, “He would pass his ideas through me. He didn’t want to put himself in front of Marc.” Demna felt like he was biding his time, working in the fashion equivalent of a German bank. He said, “I had to do things that did not really aesthetically speak to me, so it just became a job. A very, very, very good job.” He added, “I just realized, it’s not enough to make me happy for me to earn well, be home at seven, and have nice holidays in Capri.”

Frustration with the corporate fashion system led him to take a risk. In 2014, he used savings to launch his own line, Vetements (“clothes,” in French). It was billed as a design collective—key members included his brother, Guram, acting as C.E.O., and the Russian stylist Lotta Volkova—but Demna was clearly the driving creative force. He could finally dissect and rejigger and twist and repair, making the kind of deconstructed clothing that he’d wanted to make at Margiela but that the establishment considered unappealing.

He had his own touchstones, of course: Communism, post-Soviet consumerism, the Orthodox Church, knockoff culture, flea markets, metal, hip-hop, the nineties, the Internet. As a teen-ager in Tbilisi, he had found a job translating wire copy at a television news station. In 2001, when the planes hit the World Trade Center, he was conscripted, owing to his language skills, into delivering the live on-air report. “When you have insight into dirty, corrupt politics in a post-Soviet country at seventeen, you get hooked on that a bit,” he once said, explaining his habit of infusing his fashion with political and social commentary. He also wanted to imbue his clothes with attitudes that he didn’t see reflected elsewhere. He placed the shoulders on one jacket too far forward, creating a slumped, FML-ish silhouette.

Vetements was a sensation from the beginning. “Nobody seems to have consulted each other on this: They just went to shops, women and men alike; tried on the Vetements stuff; loved the way it made them look and feel; and impulsively paid up,” Sarah Mower wrote, in Vogue, of Demna’s firefighter pullovers and floral tea dresses, which evoked both grunge and an Eastern Bloc grandmother’s curtains. In 2015, the brand showed a collection at Le Depot, a Paris night club that bills itself as “le plus mythique des Cruising Gay de France! ” According to Demna, it was one of the few venues that he could afford. “But I did like that it was kind of a taboo,” he said. “I mean, fashion is probably the most gay industry—why should it be taboo for people to come to a place where, for decades, many people who have been doing fashion probably have been?” People who attended recall the show, despite overpowering bathroom aromas, as a once-in-a-lifetime fashion event. “Even taxi-drivers knew about that show,” the fashion filmmaker Loïc Prigent told me. Demna said, “Everyone came,” adding, “I found that important, somehow, especially having only always felt like I was being rejected.”

The next season, Vetements unveiled a DHL T-shirt—literally, a yellow T-shirt emblazoned with the red DHL logo. This was the latest of Demna’s diaristic touches, a Tumblr post from the still janky world of a hit brand that didn’t always know whether it would be able to pay its shipping bills. It was hailed as an immediate “capitalist kitsch” classic, especially after the company’s chairman was featured wearing it on a DHL Twitter account. Soon afterward, the Times declared, “A Once-Obscure Designer Is Now the Talk of Paris.”

Cristóbal Balenciaga was a poor boy, too. He was born in 1895 in the fishing village of Getaria, on Spain’s Atlantic coast. He could have been a priest or a boat captain, like his father, if he hadn’t become Paris’s greatest couturier—“the master of us all,” as Christian Dior deemed him. Balenciaga was also a refugee, who relocated to France when the Spanish Civil War made business untenable. Beaton dubbed him the “Basque Dick Whittington,” mocking his humble origins, but acknowledged his peerless refinement, writing, “Balenciaga uses fabrics like a sculptor working in marble.” It is necessary to quote Balenciaga’s observers because he did not grant a single interview during his fifty-year career, pursuing a recondite vision of beauty with an intensity that left room for nothing else. “The sleeve was, as is well known, Balenciaga’s obsession: everyone connected with the house remembers anguished cries of la manga and the awful sound of the master ripping one out at the last moment,” his biographer Mary Blume writes in “The Master of Us All.” Coco Chanel said, simply, “He is the only one among us who’s a real couturier.”

Balenciaga’s couture clients were the aesthetes of international society: Pauline de Rothschild, who appreciated his habit of cutting a hemline high in front, to show off the legs; Rachel (Bunny) Mellon, for whom he even made gardening clothes, including a linen blouse with his customary swept-back nape. Hard as he was on himself, Balenciaga treated his clients with a certain empathy. He was known to like “a bit of belly,” because making a dress for a lumpy matron was a more challenging exercise in craft. He demanded loyalty in return, believing that a truly elegant woman would frequent one dressmaker rather than flitting from house to house in search of the latest trend. His white-walled salon, at 10 Avenue George V, operated according to rigid codes of discretion. A vendeuse never said that she had “sold” something to a client; rather, she had “dressed” her, or had “made” her a dress. In the nineteen-fifties, women from the Spanish high bourgeoisie travelled to Paris twice a year to outfit themselves at Balenciaga. One observer wrote, “They came home embalenciagadas from head to toes, a fancy for which their husbands paid handsomely, buying and selling cotton on the black market.”

Creatively, Balenciaga was a radical. He began his career as a conventional maker of pretty clothing, but by 1950 he was moving toward the purified, architectural forms for which he became revered. He transformed European fashion by focussing on the negative space between the body and the garment, ignoring anatomical limits while the likes of Dior worshipped the waist. His designs were so abstracted that people tended to describe them using metaphors that brought the creations back down to earth—the sack dress; the tulip dress; the envelope dress; the baby-doll dress; the cocoon coat; the melon sleeve, with folds “like the skin of a plump shar-pei puppy,” as Blume writes. (As ever, there were haters. In 1951, this magazine complained of “girls whose pelvis appears to start just below the chin and who look as though they had been hacked out of an old elm stump.”) Balenciaga’s “chou” wrap was made of black gazar, a stiff silk fabric that he helped to invent. It encircled the wearer’s face like the leaves of a cabbage rose, or a giant scrunchie. In 1967, Balenciaga used ivory gazar for a wedding gown and swooping “coal scuttle” hat. The items, each cut on the bias from a single oval of fabric, form probably the most exquisite bridal ensemble that has ever been made.

In May of 1968, Balenciaga closed his atelier suddenly. Students were protesting in the streets; ready-to-wear was threatening the couture tradition. One Balenciaga client, the American socialite Mona von Bismarck, reportedly took to her bed for three days in Capri. The house was sold to a German pharmaceutical conglomerate and produced nothing but perfume until the nineteen-eighties, when the owners brought on respected designers, including, in the nineteen-nineties, Josephus Melchior Thimister, to try to revive the clothing business. In 1997, they promoted Nicolas Ghesquière, a twenty-five-year-old who was working on funeral outfits for the brand’s licensees in Japan, to serve as the head designer. (Kering, at the time called P.P.R., bought Balenciaga in 2001.) Ghesquière restored the brand to acclaim in a fifteen-year run, updating Cristóbal Balenciaga’s tradition of unusual shapes and innovative materials with such hits as a neoprene “scuba dress” with birdcage hips and knob shoulders. He was succeeded by Alexander Wang, who left in 2015, after a tepid three-year stint.

The appointment of Demna, a fashion-world insurrectionist, came as a shock. Some people loved the idea, praising Kering for hiring based on raw talent, not court politics, while others deemed the choice “risky” or “out of left field.” His first ready-to-wear show, marrying Vetements slouch with Cristóbal exactingness, was a clear triumph. “It switched something immediately,” Loïc Prigent said. “I saw the proportions change on all the editors.” Fashion authorities such as Pamela Golbin, a former chief curator of fashion at the Musée des Arts Décoratifs, saw sympathies between the master and the maverick. Golbin said, “Balenciaga stands for a certain form of perfection, and I think Demna brought that purity and dignity back to the house.”

Certain disciples of Cristóbal Balenciaga were steamed at the thought of a vulgarian in the temple. Their indignation grew as Demna made streetwear a mainstay of Balenciaga’s offerings. “I have been told to be quiet, and I have turned my eyes away, but I cannot tolerate this any longer,” the American couturier Ralph Rucci wrote on Instagram in 2018, complaining that the brand’s leadership was “without balance, respect for proportion, without quality, without integrity just the whoreish greed to sell a gym shoe, a t-shirt, a back pack.” Rucci recently posted a screenshot of a D.M. that he had sent to Demna: “I am qualified to tell you sir, that you are utterly unqualified to be the director of this house. Sneakers.” Sneakers!

According to Charbit, the C.E.O., Demna brought up the idea of resurrecting haute couture the first time they met—and then, out of a kind of superstition, didn’t mention it again until five years later. By that time, Demna had effectively earned the right to try his hand at fashion’s highest form of expression, funding the painstaking labors and precious materials that couture demands via the very sneakers that his detractors claimed would bring about the house’s desecration. The couture was also a business proposition, adding grown-up lustre to a brand image that skewed lowbrow and millennial. Demna presented the collection at the old salon at 10 Avenue George V, which he had restored to a faux-timeworn version of its past splendor, calling in a “patination team” to watermark the walls and to ash the carpets. He wanted it to look as though no one had touched it since Balenciaga left.

The first couture collection quelled all but Demna’s most diehard skeptics. It was shown the old-school way, in silence. You could hear his ski-parka opera coats rustling through the narrow corridors. There were murmurs of appreciation for a trapezoidal satin T-shirt that Demna said took three months to make, and for a clementine-colored day suit with edges that looked like they could draw blood, shown with a slick black fruit-bowl hat.

Demna’s clothes argued that you could pour just as much craft into a T-shirt as you could into a ball gown. (Charbit told me, “Demna put creativity, innovation, and effort into things that, before, people were, like, ‘Uh, we need this to sell.’ ”) But he also respected the limits of how much T-shirt you could pour into the craft. Haute-couture shows traditionally end with a wedding gown. Demna said that he’d tried to come up with something clever. In the end, he decided to replicate the 1967 oval dress. “There was no way it could be better,” he said.

Demna has never been interested in producing what, echoing Duchamp, he calls “retinal” fashion—clothing that is only pleasing to the eye. His critics say that his designs are outright ugly. Some of his supporters do, too. “Usually, there’s a thing or two each season where I’m, like, ‘O.K., he’s gone too far. This is actually just fucking hideous,’ ” Eliza Douglas, the painter and model, said, laughing. “Then I’ll realize a few days later, I’m, like, ‘Oh, my God, that is the thing.’ ” Recently, she’d gone through this process with a pair of varnished snub-nosed clogs.

His wader boots and horn-shouldered turtlenecks are extremist takes on Francis Bacon’s observation that beauty derives from strangeness in proportion. His love for off colors, iffy prints, and ersatz details recalls the provincial market stall. “He has different references, and he had the courage to use them,” Sophie Fontanel, the critic, said. “He was convinced that there was something refined, chic, in what was considered kind of plouc.” (Plouc means something like “hick.”) What people called ugliness often amounted to tension: physically comfortable pieces that induced aesthetic unease; technically immaculate clothes with outward imperfections. “There’s a dress that we really tortured,” Demna once said of a gown made of delicate black lace that his team had spent three days riddling with holes. In a reversal of fashion precedent, he was practicing sadism toward the clothes rather than accepting it from them.

The goal, of course, was to get people talking. “If it doesn’t cause any kind of reaction, it just doesn’t exist,” Demna told me one day. “That’s my biggest fear, probably.” According to a 2021 paper published by a scholar at the University of Lisbon, Demna is responsible for “introducing the meme into fashion.” An obvious example of this is his clickbait bags: the Hefty-like calfskin garbage sack, a glazed-leather IKEA-style carrier, a crinkly fifteen-hundred-dollar clutch that was made to resemble a Lay’s chip bag and came in four varieties (Classic, Limón, Salt & Vinegar, and Flamin’ Hot). The analytics firm Launchmetrics found that the Hefty-ish bag generated a “media impact value” of two million dollars in a week.

Is he for real? Throughout Demna’s career, observers have tried to figure out whether he’s a heartfelt oddball or a wily cynic. The artist and critic Hito Steyerl has likened Balenciaga’s hype machine to the Trump and Brexit campaigns, pushing products using a “dynamic of shock and subsequent normalization.” Demna is finely attuned to the attention economy. A digital native, he understands the value of creating a conversation. It doesn’t always have to be positive. This knack for getting a rise out of people made it a little hard to believe that the mood of the Gift Shop pictures wasn’t a deliberate choice, even if the aim was to grab attention rather than to cause harm.

People often worry that Demna’s jokes are on them. Douglas told me, “Over time, I’ve figured out that he’s drawn to ambiguity and walking that line and us not really knowing.” Demna has written, “The beauty of some questions is that they don’t always have an answer.” But he is unusually articulate about the thinking behind his most outré moves. He told me that he had designed the IKEA bag in the Duchampian tradition, inverting cultural hierarchies. It harked back to Margiela’s Franprix-bag tops of 1990. Above all, it drew on Demna’s personal history, recalling the four years of fashion school he’d spent lugging around his portfolio in just such a bag. He even made the bag in yellow, a colorway that you could get only if you stole it from an IKEA store. “I’ve never felt that irony was a negative,” Demna said. “Instead of getting offended, you can also laugh about it and be, like, ‘That’s fun.’ ”

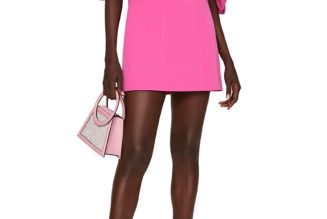

He was ambivalent, though, about some of his most ubiquitous creations. Of the Triple S sneaker: “I can’t see it anymore—you’re just sick of it.” The Speed sock-shoe: “It just makes me cringe now.” In Paris one day, he took out his phone and mentioned that he has a group chat with a few superfans who give him honest feedback on his work. One was a communications student in the U.K. Others lived in the U.S., doing who knows what. They’d never met in real life, but, Demna said, “they know more about my world than probably anybody.” One of them had just sent him a message about a skintight, bubble-gum-colored minidress with a repeating Balenciaga logo.

“He was, like, ‘Did you actually do this, or did the commercial team make you?’ ”

“What did you answer?” I asked.

“I said that I did it, but, obviously, it wasn’t something that I woke up and felt like I had to do.”

In 2021, Demna agreed to accompany Kim Kardashian to the Met Gala, the prom of fashion. He was feeling anxious about having to walk the red carpet and then make small talk with a bunch of very famous people he had never met. The dress code was “American Independence.” Demna and Kardashian showed up in matching all-black ensembles, their faces obscured by opaque black masks. All that was missing were Grim Reaper scythes.

“I was kind of terrified,” Demna told me. “So that was my solution. Of course, there was a conceptual twist to it, given the person that I was with.” Until recently, he has insisted on being photographed in an ovoid polyurethane face shield that he developed with engineers at Mercedes-Benz. (I tried one on at the brand’s Avenue George V salon. It was surprisingly light. I felt invincible. I would wear it, supposing that I had fifty-six hundred dollars for a face shield and a completely different life.) He said that he covered his face because he had issues with his body, especially after seeing a picture of himself, taken at a conference, “with, like, a triple chin.” I pointed out that wearing a mask was likely to make people look at him more. “Yes, ultimately it does,” he admitted. “I feel that sometimes I do that—somehow subconsciously looking for that attention.” He giggled a little. “Oh, my God, it’s weird. This is something I discussed with my therapist a lot.”

“I absolutely do not believe there will be a loss,” Demna said, sitting at his usual table at Kronenhalle, a wood-panelled restaurant in Zurich with Matisses and Mirós hanging on the walls. He had ordered plant-based chicken and rösti. To drink, a tiny pitcher of lemon juice. He was fully embalenciagado, with silver ball hoops in his ears. I had asked him whether the advertising scandal might result in a new era of lost nerve and chastened creativity. “I’m very much back on the autoroute of dressmaking,” he said, pushing a sleeve all the way to his shoulder, revealing a tattoo of his name. “But my dilemma right now is finding a balance between being about clothes but also not being too conservative or classic.”

It was a gray, misty Monday in February. Before lunch, we had gone for a walk. Demna had chosen as our meeting place the Fraumünster, a copper-spired church not far from the garden where he and Gomez married, in 2017. “Looks like Hogwarts, doesn’t it?” he said. The couple had spent the weekend bingeing a Netflix thriller called “Alice in Borderland.” They were packing for an impending move to the French countryside, near Geneva. Demna had just had an appointment to take care of some paperwork, and an official had asked the reason for their move. “I don’t speak Swiss German, so it was a bit awkward,” he recalled. “Well, actually, that was kind of an answer. I was, like, ‘Yeah, that’s one of the reasons: because I cannot understand what you’re saying.’ ”

As we toured Zurich’s shopping district, Demna’s cocooning hoodie and club-kid pants drew a look or two. (The feeling was mutual. “I think people are especially badly dressed in Zurich,” he told me. “I don’t know what it is. It’s really—I am quite amazed.”) The silhouette, I realized later, was classic Cristóbal, with a too-long T-shirt peeking out from a sweatshirt, adding volume like the underlayer of a baby-doll dress.

At Kronenhalle, the plates looked familiar—white porcelain, with cobalt rims and a stodgy monogram. I remembered drinking tea, the first time I met Demna, from a similar set, except that cup had read “Balenciaga Hotels & Resorts.” (There is, of course, no such thing.) The teacup had mildly irritated me at the time. Does everything need to be a gag? I’d thought. Does everything need to be a product? Now, in his oldfangled hangout, I saw it more as a wry expression of fondness.

Troll or truthteller, idealist or ironist? Demna has been all and none, playing in the uncomfortable, fertile space of the accepted paradox. Now he was declaring his “mask period” over. Memes were out, as were flashy shows and all the other “easy but exciting” distractions that had “lured” him away from the fundamentals. “I could make ten IKEA bags, but it’s by letting go of that comfort zone that you can grow,” he told me. “What would be the most shocking thing for my audience? I’m talking about people who know my work. Would it be another provocative thing? Or would it be actually going back to my roots and making the coat that you never want to stop wearing?”

Was this a foregone conclusion, or yet another one of Demna’s questions without answers? ♦