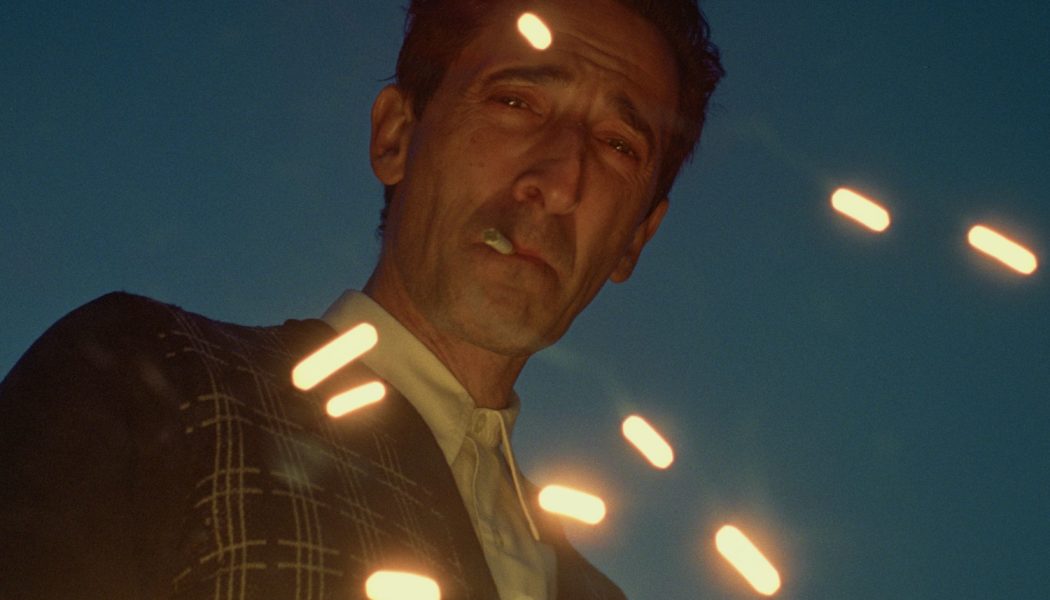

Brady Corbet’s 3.5-hour saga is a tale of one man’s journey through architecture and assimilation — and one of the year’s best films. The director tells The Verge how he got away with it.

Share this story

The expectations for The Brutalist are high. Actor-turned-director Brady Corbet already took home the Silver Lion at the Venice International Film Festival in September. And now he enters Hollywood’s big award season with seven Golden Globe nominations, including Director of a Motion Picture, Screenplay of a Motion Picture, and Drama Motion Picture.

The Brutalist is a historical epic that follows László Tóth (Adrien Brody), a renowned Bauhaus architect, who makes his way from Budapest to Pennsylvania after the Holocaust. There he meets the Van Burens, a wealthy family with vast resources — the kind that could revive the career of a talented architect. Though a series of events would derail the initial work, László is resilient and with time, is invited to design a massive, ambitious community center.

After intermission — yes, there’s an intermission — we see László living off of the Van Burens’ land. He’s even been able to use their connections to reunite his family who were forcibly separated from him during the war. But if László sounds easy to root for, he’s not. Because at the corner of every win comes a loss. And it’s the booze, drugs, and philandering that wear him down. Eventually, The Brutalist departs Pennsylvania for a marble quarry in Carrara, Italy for the film’s most startling scene.

I spoke with Brady Corbet, who co-wrote the script with his wife Mona Fastvold, and we discussed his prickly protagonist, the film’s nearly four-hour runtime, and why rich people feel they need to collect artists more than their art.

The Verge: At the heart of The Brutalist is a story about doing whatever it takes to survive during uncertain times. What made this story so urgent for you?

Brady Corbet: I really always try to work with themes that will continue to be relevant for me, irrespective of how long it takes to get them off the ground. When I made Childhood or Vox Lux or The Brutalist, they’re films that are historically steeped, thematically rich. It’s rich material. I had suspected when we got to page 173 or whatever and wrote the end that it might take some time to get this one off the ground.

And the film is dealing with themes of individualism and capitalism and immigration and assimilation, and these are all things that I think that virtually anyone has some real experience with in whatever line of work that they’re doing. Obviously I know how much journalists have to fight to cover what they want to cover and get paid a living wage, and it’s become increasingly difficult for artists, writers, architects, filmmakers, you name it. I think it’s something that anyone can relate to. And of course, as everyone is anticipating how the new administration will be handling immigration, of course, I think it’s especially on top of mind right now for viewers.

The moment when László tells Audrey, “I’m not what I expected either” really spoke to this character’s survival instincts. Can you talk about finding that with Adrien Brody?

Adrien’s a really, really smart guy. And not to speak ill of performers, but he is uncommonly attuned to what this film was doing in terms of its themes and really everything that it had on its mind. I think he just really understood the material and he understood where to put the emphasis on the syllable. And I think that when I met him, he has this really graceful quality, and he also reminds me of a performer of another era.

For me, he’s like Gregory Peck or early De Niro. As we are moving into an era where I find it very difficult actually to cast period pieces, there’s a lot of actors that I love that have a lot of plastic surgery, and it’s very difficult because you can’t cast someone that’s had so much plastic surgery in a film that takes place prior to 1975. I really hold on to these performers, Men, women, and young people, so many young people that are getting plastic surgery — like 18, 19 years old that just are natural. And I think that Adrien, he has this anguish that’s there as well. I don’t know precisely where that comes from, but it’s clear to me that this is a person that’s lived a lot. He’s squeezed a lot of juice out of the lemon.

And I think that that was just all very appealing to me. I think that of course, his heritage was a factor. I knew about his background. I was aware of the fact that his mother had fled Hungary in 1956 during the revolution. He was uniquely well suited for the role.

There’s a certain type of wealthy person that loves to collect people. Guy Pearce’s character, Harrison Lee Van Buren, is the pinnacle of a people collector.

I’m so fascinated by the patrons that don’t want to just collect the work. They want to collect the artists.

Guy really understood it immediately. I think when he read the screenplay, he fully comprehended the piece. The movie was self-selecting, I would say, because all of the folks that stuck with the project as it fell apart and came back together so many times. They all had a really strong point of reference for what this was about.

It’s just such a specific person. I see them everywhere.

It absolutely is. Listen, I think that the sequence in Carrara, and when it really starts getting into when the reality becomes liquid and it reaches Greek mythical status after two and a half hours. What was so important to me about Carrara is that Carrara marble is this material that should not be possessed, and yet it lines our kitchens and bathrooms. But the material — it’ll be gone in 500 years. Those mountains will not exist. And that’s incredibly disturbing because they’re like Swiss cheese right now, of course, and there are constant rock slides.

It’s not as dangerous as it was 70 years ago where people literally were chopping off their hands every single day, but it’s still quite dangerous. There are helicopter pads and they serve two purposes there. The first purpose is to carry out people that get badly injured. The second reason is that many buyers like to fly in and choose a slab for their home or a sculpture or whatever.

It’s this VIP thing, which I feel is totally hilarious and disturbing. And for me, I think that that theme of that which cannot and should not be possessed. The visual allegories were very rich in that place.

Throughout the first act, you’re sliding in all these romantic historical notions of Pennsylvania. Why’d the story just need to take place there? What was it about Pennsylvania that was important for you?

In 1935 when the Bauhaus Dessau was shut down by the Nazis, Walter Gropius was able to get many professors, proteges, artists, designers stationed at universities in the Northeast predominantly. There is a reason that so many of the greats ended up in that part of the country. That’s specifically why, but for me — especially because of Paul Rudolph and Louis Kahn — it was just important to set the film in a place that is very, very rich architecturally.

And it was actually only through the process of working on the movie that I really learned so much about the history of Pennsylvania. And that’s the thing that’s interesting about making a film is that it’s important that you know enough to make a movie on the subject matter, but also, there should be some space for you to discover something as well because you’re going to be working on it for so many years that it has to be exploratory. I want to be discovering something with the audience. I’m not that interested in telling the audience or teaching the audience.

(Light spoilers follow.)

As a director, how do you go about building trust with the audience to stay engaged through the runtime — intermission and all?

I just think it’s intuitive. I watch good stuff. I watch bad stuff. I watch everything. And cinema is a language at this point that I feel pretty well-versed in. I feel pretty fluent at this point. And I think that it becomes second nature. What I just keep saying about this film is that the film is long, but it’s not durational cinema. There’s a lot of extraordinary durational cinema. I love the work of Lissandra Alonso or Bela Tarr or Miklós Jancsó, who was also the father of my editor, David Jancsó. But with this movie that wasn’t part of its makeup or intention or design or editorial.

It is interesting because, and for some viewers, I think people can sometimes find it very frustrating because I intentionally omit a lot of the stuff that, for me, I feel like the first 30 minutes of most movies, it’s just so much exposition. It’s just they’re telling you about these characters’ backgrounds and exactly what they’ve been through. And I just don’t think that’s very interesting. I want to meet a compelling stranger.

And I want to get to know them over the course of the movie. I don’t want to watch a movie where in the first five to 10 minutes you know exactly how it’s going to end. And that’s almost everything.

It’s very, very rare. And what was interesting for me about this was in terms of subverting the classical structure, I was like, “It’s a natural place to end the movie with a retrospective of this character’s work.” But what’s very unusual, beyond the fact that formally it’s quite unusual — a lot of it was shot on DigiBeta, and it’s a big adjustment to jump from 1959 to 1980 — is that Adrien’s character is not given a voice in that sequence. He is physically present for his achievement, but he’s perhaps not mentally present for his achievement. His wife is dead. And there’s a great quote, and it’s one of the southern Gothic writers. I don’t know if it’s Flannery O’Connor or Faulkner or Cormac McCarthy. It’s one of them. But there’s a great quote, which is, “Man’s spirit is exhausted at the peak of its achievement. His noon signals the onset of midnight.”

[Ed note: It’s Cormac McCarthy and the exact quote is “His spirit is exhausted at the peak of its achievement. His meridian is at once his darkening and the evening of his day.”]

And I think that’s very true. It’s this interesting thing where these moments that for the public or for anyone on the outside looking in seemed to be these moments of glory. You generally are spiritually too exhausted to really appreciate it in a way. And it was important for me to do something that was, yes, it’s absolutely classical in terms of A, B, and C, but the quality and the tone is there’s a real melancholy. And there’s a lot going on at the end of the movie. Ecstasy is always accompanied by agony and vice versa. And it’s important for the films to represent that.

And then the last thing that I’d like to say is that I think that I’ve always been disturbed by the way survivors are portrayed in cinema, which is that they’re frequently altruistic. They’re like saints. My problem with that is that it suggests that we can only empathize with someone if they’re perfect. And for Adrien’s character, it was important to me that it is a love story. He loves his wife very deeply, but he also has a wandering eye. He’s very much a man of the mid-century. He’s a philanderer. Yet both of these things can be true. We can empathize with him even when he is behaving badly.

The high cost of making things hangs really heavy on László and his entire family. Did you know that in the end — when we reached the epilogue — that it’d be worth it?

I don’t know if it is worth it for him. I don’t know. I think that that’s something which is a little bit ambiguous about the film’s conclusion, is that when you speak to most people at the end of their lives, they usually say, “Take it from me, spend more time with your kids.”