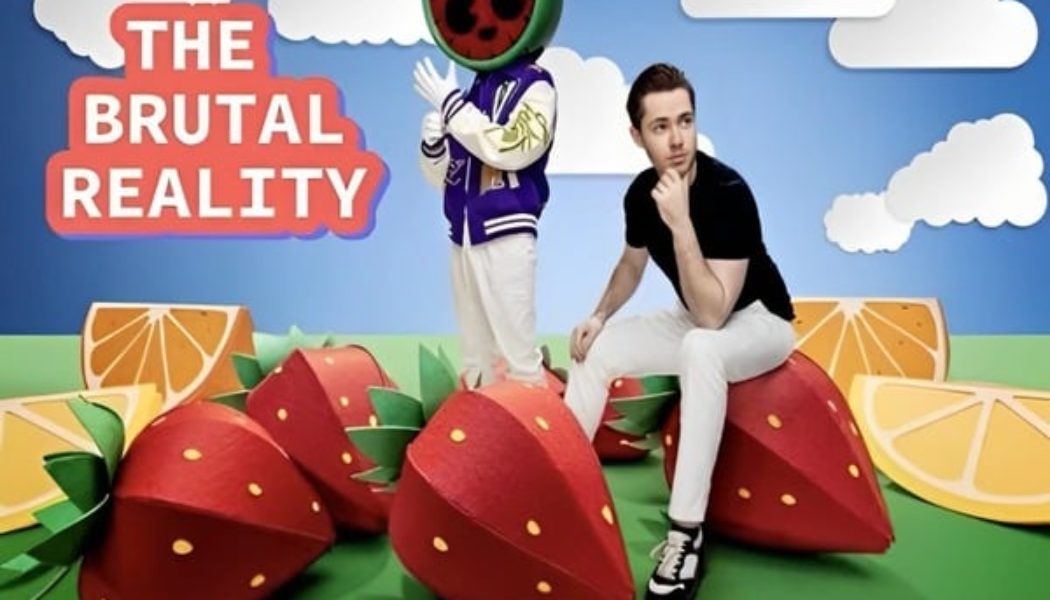

The following MBW op/ed comes from Stef Van Vugt (pictured), the founder of Fruits Music, a label-cum-playlist company that has racked up tens of billions of plays on Spotify and other services. Netherlands-headquartered Fruits Music is home to playlist brands such as Dance Fruits and LoFi Fruits, and is represented by its famous Melon brand identity.

Hi. It’s been a minute since I last published an op/ed on MBW. Those of you who might have read this op/ed on AI or this op/ed on royalties will know I try to see around corners, and always speak my mind. So here I go again.

AI music startups such as Suno – which just raised $125 million in funding – are creating better-sounding music than the majority of newly released human-made songs on music streaming services.

There. Doesn’t it feel good to see someone state things as they actually are?

(Qualifying that statement, which isn’t as controversial as it first appears: around 120,000 mainly human-made tracks are being uploaded to streaming music services today. And of the 100 million-plus tracks on these services today, around 25 million weren’t even played once in the past 12 months.)

This is indicative of a ‘new normal’ that’s already taking hold of today’s music business – and will define the music business of tomorrow.

It is not impossible for the largest traditional music rightsholders to thrive in this ‘new normal’. But, due to a number of threats to their dominance, the global business’s power balance is irrevocably changing.

In fact, I predict that new rightsholders — and, particularly, AI-driven music — will continue to take market share from the largest music rightsholders in the years ahead.

Threat 1: Platforms, not labels, are becoming music’s primary influencers (and content owners?)

The music and entertainment rights industry, like most events in life, follows repeated patterns.

How many times have we seen this story:

- New innovative company develops a product to monetize rights, which benefits users;

- Legacy rightsholders license their content for a high price for short-term gain;

- New innovative company diversifies its offerings (maybe creating its own content) to reduce reliance on legacy rightsholders;

- New innovative company grows in size, power and becomes profitable;

- Legacy rightholders withdraw their rights from the new innovative company product and/or try to renegotiate again;

- New innovative company has, by this point, built the necessary leverage and diversification to thrive without traditional legacy rightsholders;

- Legacy rightsholders scramble to catch up. Late to the party, they try duplicating the innovative company’s product.

This aptly describes the “Year of Efficiency”, i.e. a profit-maximizing period in which it will, chasing that efficiency, inevitably reduce human influence on playlists and streaming outcomes.

Meanwhile, many of us in this business continue to grow our collective addiction to Spotify’s “Discovery Mode” aka ‘Algorithmic Discovery’.

If we ‘choose’ to participate in Discovery Mode – and it’s not much of a ‘choice’ if Spotify makes it a necessity to grow audiences – this potentially raises

“Spotify’s ‘year of efficiency’ will inevitably reduce human influence on playlists and streaming outcomes.” This is akin to what we are already experiencing on social media platforms such as TikTok, where there is no ‘mainstream’ music. Talking of TikTok… I’ve always liked the phrase, “Timing is a funny thing, and the most funny thing is the most likely outcome.” In January 2024, UMG issued a theatrical statement defending copyright holders against TikTok. On the day of the statement, I noted that a funny outcome would be if “Taylor Swift fans united together as they often do and forced [the powers that be] to reinstate her songs on TikTok.” Guess what happened next? (As a wise man recently said to me: “TikTok is like a movie; it will keep entertaining… with or without the music.”) This all raises one big question: What now needs to happen before music streaming services like Spotify can wield the same power vs. music rightsholders as a big tech giant like do not collect performance royalties on Epidemic Sound’s content. That is a potential margin saver for Spotify if this content is sufficiently popular; and (ii) Spotify is most definitely still stuffing its own key playlists and algorithms with this music as much as possible. Do you even realize how in control Spotify is over its playlist/algorithmic audience? Below, you’ll find a summary of the top ~25 most consumed global playlists on Spotify for the fourth week of 2024, in order of worldwide streams, according to my research. I’ve color-coded it thusly: Do you see what I see? Correct: there are no longer any third-party playlists in the top 25 most popular Spotify playlists. All of these playlists, each of which exhibits a business model threat to the majors (RE: color coding) are owned and/or controlled by Spotify. As MBW readers will know, the traditional rightsholders have been working hard to fend off the threat from both ‘noise’ and AI-generated content from their share of streaming’s royalty pool. Most notably (and perhaps surprisingly, considering my business in music to date) I’m in favor of the new 1,000-stream payout threshold on Spotify and the demonetization of ‘noise’ content that’s under two minutes in length. (I actually suggested some alternative, and better, measures to make royalty payouts fairer in this op/ed.) We’ve also seen insist on “protection” against the music royalty pool being diluted by AI-generated tracks on platforms like TikTok. Yet moves like this won’t ultimately be enough to deal with the ultimate problem from AI-generated music: People are just going to love making it. The AI genie is out of the bottle. You can sue, opt-out, or attempt to eliminate all AI startups. But that does not address their attraction to, and benefits for, the average consumer. “the ultimate problem for rightsholders from AI-generated music? People are just going to love making it.” Average consumers will use open-source developed models of AI content generation natively in the future. They will be able to create endless short audio clips from their mother’s basement, which may gain traction on social media platforms and then prompt the release of their song’s full version on streaming services. They could end up performing in front of an audience of real fans, with hardly any musical background at all. Who’s a ‘listener’? Who’s a ‘music-maker’? Who cares! How are music rightsholders going to sue/prevent regular individuals with nothing to lose from creating and distributing millions of music tracks? How can you stop people using natively-operating, open-source-trained, AI music models? The major music rightsholders are already pressing home their advantage today to help maintain their market share. Look at

“Music rightsholders will need to alter their focus to compete for attention, relying on those who can better influence, manage, and amplify social media and streaming algorithms.” Moves like this won’t be enough for the majors to completely ‘protect’ against tomorrow’s threats, however. To do that, they’re going to have to play offense as well as defense. Music rightsholders will need to alter their focus to compete for attention, relying on those who can better influence, manage, and amplify social media and streaming algorithms. Some ways to accomplish this include: (i) managing micro-influencers; (ii) operating popular social media pages; (iii) directly managing brand or artist audiences; (iv) scaling digital marketing campaigns that drive traffic to platforms that trigger algorithms; (v) Building carefully-curated ecosystems such as playlists or reusable attention assets. Another area of opportunity for the majors? Developing A&R algorithms that identify potential audio content, including snippets, on social media platforms that can then be developed into hit streaming songs (aka ‘internet songs’). While I continue to see certain companies refuse to change in these ways, I have noticed some that are paying attention – companies like HYBE and Music Business Worldwide

Threat 2: The increased dilution of market share by AI-generated music

The opportunity: A change in business models for the majors