I n the middle of August this year, three legends of the music industry died within 72 hours of each other: founder of A&M Records Jerry Moss; music lawyer Abe Somer; and my father, the “Black Godfather” himself, Clarence Avant. These three men helped define the recording industry of the past six decades, and what’s more, they were inseparable best friends.

Somer, Moss, and Avant met in New York City in the early 1960s, and in the six decades since, never left one another’s side, never once let their “soul contract” expire. The synchronicity of them passing in the space of just a few days makes me wonder if they simply couldn’t face being on the planet when one of the others was gone —that’s how close they were.

Abe Somer’s career includes almost too many highlights to list: He helped Lou Adler create the Monterey Pop Festival, where Somer’s guest that weekend, Clive Davis, heard Janis Joplin and subsequently signed her; Somer’s pal, Jerry Moss, signed Joe Cocker after Somer and Moss attended Woodstock together; and in 1971, Somer helped the Rolling Stones ink the then-biggest music contract ever, securing for the band a deal worth $1 million plus 10 percent royalty per album. The roster of other musicians whose careers he helped may never be matched: Beyond the Stones, there were the Beach Boys, the Mamas and the Papas, Neil Diamond, the Doors.

Jerry Moss and Herb Alpert had established A&M Records in 1962 (Abe Somer would go on to be A&M’s counsel for many years). Like Somer’s list of clients, Moss’ roll call of acts on A&M is Hall of Fame level: a very partial list would include the Carpenters, Cat Stevens, Supertramp, the Sex Pistols (for one week only!), Sting and the Police, Suzanne Vega, Janet Jackson, Bryan Adams, the Go-Go’s, Burt Bacharach, Barry White, Sheryl Crow … and on and on.

As for my dad, well, he was part manager, part mentor, part power broker; a consultant, consigliere, and counselor, and most of all, a trailblazer, helping the careers of the likes of Lalo Schifrin, Jimmy Jam and Terry Lewis, L.A. Reid and Babyface, Alexander O’Neal, Hank Aaron, Jim Brown, Andrew Young, Bill Clinton — like Somer and Moss, the recipients of his influence could fill this magazine’s pages.

My father first revealed the power of his famous negotiating skills in the late 1960s, when he brought Moss the chance to sign a legendary jazz producer, Creed Taylor, to A&M. Moss pointed out that Taylor was already signed elsewhere for $35,000 — comically ignoring that minor issue of an established contract, my father asked for a total package of $450,000 for Creed, and Moss ponied up.

Establishing his own label in 1969, Sussex Records (named, puckishly, from a mixture of “success” and “sex”), my father helped bring Bill Withers to prominence, as well as Sixto Rodriguez (who also, sadly, died recently), as well as a host of white acts, including Dennis Coffey and his seminal track, “Scorpio.” It was rare for a Black-run label to include white artists like Coffey, and the Gallery, who gave my father his first Number One hit (“It’s So Nice to Be With You”), but as he says in The Black Godfather, the Netflix documentary we made about his life, “Who gives a shit what he is? It’s music.”

But by the mid-Seventies my father would overextend himself, establishing the only Black-owned radio station in Los Angeles at the time, KAGB, but he didn’t know enough about radio to make it work. Money problems quickly piled up. He could no longer pay Withers, who left Sussex; this broke my father’s heart, and mine (I had already been devastated at Bill’s wedding when I, at age five, had realized he wouldn’t in fact be marrying me). My family faced losing our house, our entire world.

And that’s when my father would stumble upon his mantra:

“I don’t have problems — I have friends.”

After he opened the envelope and saw the check, my father sat in his car sobbing; he didn’t have problems, he had friends.

One day in the middle of my father’s looming financial implosion, Moss called him.

“Come over,” he said, “I need you to look at a contract … ”

My father drove from our home in Trousdale Estates to the A&M lot, but when my dad arrived, suddenly Moss didn’t want him to look at the contract after all. “Read it when you get home,” Moss said, handing my dad a large manila envelope.

“You made me drive all the way across town and now you don’t want me to read it?” Clarence said, ignoring the fact that our house was less than 15 minutes from Jerry’s on North LaBrea.

Once my dad got in his car and drove away, a nagging feeling that something was off caused him to pull over to a side street off of Sunset. There, he opened the envelope and found what appeared to be nothing more than a fake contract … as well as a smaller envelope, inside which was a check, and a note from Jerry Moss:

“Clarence: Take care of your family. Pay us back when you’re ready. We love you. Jerry and Herb.”

My father sat in his car sobbing; he didn’t have problems, he had friends. Along with significant help from a host of other dear industry buddies, Moss and Alpert’s act of extreme love and generosity helped my father save our world and go on to establish Tabu Records in 1975. Eventually my father — a man who grew up in the Jim Crow South, picked cotton and tobacco from the age of six, and was poor enough that he’d had to eat chicken-feet soup and carry a single sweet potato to school for his lunch — would become chairman of the board at Motown Records, support various political campaigns, and eventually become a dear friend to Barack and Michelle Obama. (He paid all his friends back, too.) As Pharrell Williams said in homage: “He is the ultimate example of what change looks like … and what the success of change looks like.… He was a godfather to the Black dream and a godfather to the American dream.”

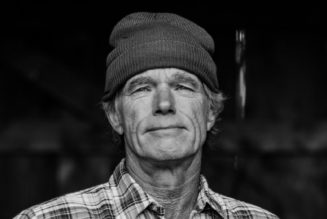

Moss, Somer, Avant (from left) together in May.

Photo courtesy of the Avant family

Sometime in the late Sixties, Abe Somer had brought my parents to a party hosted by Dinah Shore in the Trousdale Estates, a secluded corner in the north of Beverly Hills. My father, loving its energy because it reminded him of his childhood home in North Carolina, declared that night that if he ever could afford to live there, he would.

But in the late Sixties, Black folks lived in Baldwin Hills, not Beverly Hills. My father’s boss at the time, talent manager Joe Glaser, urged my dad to buy a place in Trousdale anyway —he even fronted my father the down payment. When Glaser died in 1969, my father figured he’d have to pay the estate back, until Glaser’s (and Al Capone’s!) lawyer, Sidney Korshak, called my dad, said, “The loan is forgiven,” and abruptly hung up.

Somer subsequently helped my father build Sussex Records and assisted in orchestrating the deals with Withers, Coffey, and Rodriguez. But Somer was also a staple in my life growing up — he always showed up. When, in December 2020, my mother, Jacqueline Avant, was shot by an intruder in that very house in Trousdale, Somer and Moss were the first people at my home after she died. Their presence let me know that however I was feeling at the devastating loss of my mother, we would all get through this together.

I’ve recently written a book, Think You’ll Be Happy, about my mother’s life, and dealing with grief, and though my focus in that book has been on telling her story and helping readers move positively through loss with grit, grace, and gratitude, my father and his circle of friends figure heavily, too. I was so fortunate to grow up with these titans in my life; they were creative and larger-than-life and pushed even us kids to excel.

Moss, especially, realized early that music was everything to me: One night in 1981, he came to our house for one of his regular dinner dates, and at some point during the meal, asked me, then newly a teenager, what I wanted to be when I was older.

“I just want to really be my own girl,” I said, paraphrasing Stevie Nicks and Tom Petty. From that moment on, impressed by my burgeoning self-confidence, Moss would send me gift boxes filled with pressings of his forthcoming releases, including records by the band that came to be my favorite of all, the Police. It was Moss who took me to the Hollywood Park Racetrack on Oct. 6, 1983, to attend their Synchronicity tour (he’d earlier taken me to the Ghost in the Machine tour, too). There I was, 15 years old, mouthing the words to my favorite song of all, “Tea in the Sahara,” while my parents looked on, taken aback, by my word-for-word knowledge of every single Sting song. At one point I turned to Moss, and quoting the lyrics of “Tea in the Sahara,” asked “What do you think it is that the ‘sisters and I’ wish for before they die?”

Moss said, “One day you’re going to come work for me.”

And I did. At the start of my career I would work for A&M Records in R&B promotions and marketing, in the same lot where Moss had handed my father the check that had saved my family. As for that incredible act of generosity to my family, Moss always said that he wasn’t about to let his friends sink, which dovetailed nicely with my mother’s mantra that we would sink or swim together as a family, just as it inspired my own, too (well, mine is stolen from — who else? — Sting). It’s a mantra I’ve had to lean on heavily after the twin heartbreaking losses of my mother and father: “When the world is running down, you make the best of what’s still around.”

As of May 2023, though, at least the three wise men of music, Moss, Somer, and Avant, were still around. That month, they and their extended families gathered at Moss’ house for his 88th-birthday celebration. Still dapper in a silk shirt and jacket, Moss remained an impressive figure — well over six feet, still sparkling, still handsome, still charismatic. Across the table from him sat Somer, and next to him, my father, who, though still deeply mourning the loss of my mother, was able to at least try to be his usual, puckish self, employing swears like the rest of us use prepositions. Though we didn’t know it at the time, this was to be the final scene of this extraordinary buddy movie — just three months later these three men, whose friendship had never wavered, and who had been at the vanguard of the music business for the past 60 years, would be gone.

At one point that day, I saw my father fussing in the space between himself and Moss, and I wondered if he’d dropped his napkin or spilled some food … but no — he had simply slipped his hand in Moss’, and there they sat, for the next half an hour, holding onto each other like kindergarten besties. Now, faced with their imminent end, they sat quietly in the love of each other one last time, neither of them having problems, just friends.

Nicole Avant is the author of the new book, Think You’ll Be Happy, available now.