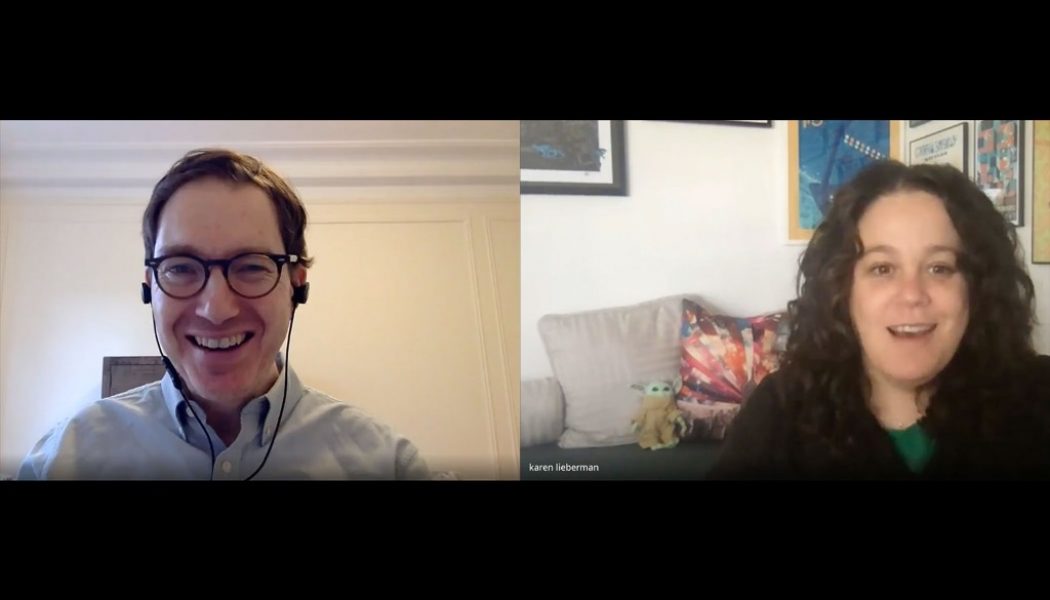

Karen Lieberman, vp sales and digital for Disney Music Group, and Jonathan Linden, partner in Round Room Live, the company behind Baby Shark Live! and Peppa Pig Live!, discuss their strategies for success in the children’s music sector and how the COVID-19 pandemic has affected their respective businesses

For those who think that gauging the musical tastes of children today is simply a matter of consulting the world’s growing trove of data, consider this: Most kids don’t subscribe to streaming services or purchase tickets to live shows — they don’t even have their own social media accounts.

“If you look at the demographics, they don’t represent children, they represent parents,” says Karen Lieberman, vp sales and digital for Disney Music Group, which runs point on physical and digital sales, streaming, digital marketing — including social media, voice activation and emerging technology — and data/analytics. “Sometimes we’ll have a third party tell us that they’ve noticed some interesting stats — that we actually appeal to 35-year-olds — and we explain that we appeal to the children of 35-year-olds.”

Jonathan Linden and Stephen Shaw, partners and co-presidents of Round Room Live, which produces live events geared toward children and families, faced a different issue when weighing the potential of expanding the YouTube music video “Baby Shark Dance” into a touring property. With over 5 billion views, “Baby Shark” was the second most-watched clip in the history of the platform, but with that many people pressing play, the data and statistics can be overwhelming, making it “hard to navigate your way through the details,” says Linden.

Round Room, which is majority-owned by Entertainment One, has scored wins with adaptations of Nick Jr.’s Peppa Pig series and Disney Junior’s PJ Masks, which Linden says has taken in revenues of $25 million since debuting in 2017. Though children’s TV shows and movies are proven fodder for live productions, a single YouTube video had never before served as the basis for a live production. “We took a bit of a risk on it,” says Linden, who negotiated with the owner of “Baby Shark,” SmartStudy of South Korea, for over three months to land the deal. “People we know in the business were surprised. They said, ‘Nobody really knows the characters beyond the song.’ We took that as an interesting challenge.”

Lieberman, Linden and their colleagues have surmounted these and other hurdles to rack up some significant successes over the past year. According to Nielsen Music/MRC Data, Disney Music Group has captured over 52% of the children’s market in the first quarter of 2020, compared with 42.66% for all of 2019, and, Lieberman says, its playlists generate more than 3 million streams a day across all platforms.

Although Round Room does not report its grosses to Billboard, Boxscore data shows that Baby Shark Live! — which was developed into a 75-minute, two-act production with 20 songs that launched in October 2019 — grossed $1.24 million and sold 31,881 tickets over 15 shows. (Linden puts the total number of tickets sold at 100,000.) Blippi Live!, another show based on a YouTube character that launched this year, grossed $406,232 and sold 9,999 tickets over six shows since Feb. 4, 2020. (Linden says the production sold 50,000 tickets in five weeks of pre-pandemic performances.)

Billboard brought these two veteran executives together in a video conference to talk about the state of the children’s music business from both the recorded and live sectors. Lieberman has held sales and marketing positions at Kobalt, Sony and Island Def Jam; Canadian native Linden has worked at Michael Cohl’s Concert Productions International and at Live Nation. They discussed which data they find most useful; the tricks to engaging, rather than annoying, parents; strategies for navigating the kids’ business through a pandemic; and why starting a children’s playlist with a certain megahit from Moana could actually be a bad idea.

How has the COVID-19 pandemic affected your businesses?

Linden Like everybody else, we’re navigating the new landscape as it happens. All of our tours and experiences are off the road, and we’re trying to do everything we can to get a return to normal. Baby Shark [Live!] was scheduled to be a 17-week tour that started in February, and we got through two-and-a-half weeks. It’s scheduled to start again on Sept. 8, and we continue to be hopeful that this fall, kids will go back to school and people will be ready to go back to theaters.

Lieberman The music group has actually held pretty strong. We do have a concerts division, which is on pause for the moment. But on the streaming side we’ve seen tremendous growth — not just year over year, but quarter over quarter — and we’re seeing it across all of our partners. We see a lot of activity happening with our classic music, but also things that would be nostalgia for people who are now young adults. The original High School Musical, The Goofy Movie and other products of the early 2000s have been performing very well. We’ve also used music as a way to bring comfort to people. We worked with ABC, another arm of the Walt Disney Company, to put together The Disney Family Singalong, the second edition of which will air on Mother’s Day. We’ve extended it to our Disney music socials as well — several times a week we post singalong clips from different talent across the Disney spectrum and friends of Disney and beyond. Those have been performing extremely well.

Can you share any numbers on streaming growth?

Lieberman Based on Nielsen data, we have a 51% share of the children’s music genre year to date. Last year we had about 37% for the same period. Our Disney Hits playlist is our flagship playlist and exists across all of our [digital service provider] partners. On Spotify, where follower counts are public, we have crossed 3.1 million followers on that playlist. Before [the pandemic], our plays across audio platforms globally tended to hover from 2 million to 2.2 million streams a day. We have now surpassed 3 million streams a day. Some days, we far exceed that.

Jonathan, there are some predictions that concerts and other live productions won’t resume until next year — and as late as fall 2021. What will Round Room do if that comes to pass?

Linden Everyone in the broader live entertainment business from Broadway to pro sports to Coachella are waiting to see how things evolve. We moved all of our projects to 2021 and our Blippi Live! tour which was to launch at the end of May has been moved to Feb. 2021. The only tour we have planned for 2020 is Baby Shark Live! which we hope can return in September. We always want to ensure that the experience for our fans is comfortable and safe and we will continue to monitor events to best ensure that we meet that objective. We also feel confident that when the time is right people will be anxious to be out in a group singing and dancing with their children.

With touring on pause have you considered livestreaming?

Linden We haven’t done a livestream channel. I’m not sure we would have enough content for that, but we’re trying to keep our ticket buyers and followers engaged through social media and different channels. To your larger point, based on the agreements, relationships, contacts and [intellectual property] we have, we have been thinking about creative ideas until people can return to theaters. I think that will be an interesting side effect of this entire situation.

Whether it’s live or recorded music, how does holding the attention of children and tweens differ from holding the attention of teens and adults?

Linden We create our productions in ways that fit with their followers. PJ Masks Live, for example, skews a little bit older, so it’s structured almost like a first Broadway experience: There’s real singing and dancing; there’s a plot; there’s a villain; and you have to follow things a bit more closely. Baby Shark Live! skews younger and is closer to a child’s first concert. The music has to be really dynamic. It has to get kids out of their seats. We do an original cast recording of our shows, and streams of the PJ Masks cast recording are up similar to some of the Disney music Karen described. The cast recording is different from the live show, where the songs are quicker and shorter, and lead one into the other so that you have kids dancing in the aisles.

Lieberman Ever since we launched Disney Hits almost five years ago, we have spent a lot of time curating it in a way that keeps it flowing and keeps it sticky. Disney Hits tends to be songs from [1989’s] The Little Mermaid forward, and we pay attention to the skip rates and how many songs people listen to in a given session, and we move things around.

I’ll give you an example: We found that “How Far I’ll Go” from Moana is one of our top-performing songs across all platforms. However, if you were listening on a voice-activated device, we found that if you requested Disney Hits, it would kick right into that song because it was the first song on the playlist. But that song has a very quiet start, and it left people questioning whether the playlist had started or if they needed to raise the volume. So we moved that song, and now the playlist starts with something where people know quickly that they’re getting what they’re asking for, because voice [activation] is such an essential part of this for us. On social media we make sure to use shorter clips to accommodate different attention spans.

Finally, we find a lot of success when we bridge generations. On voice devices, the Disney Hits Challenge is a four-question quiz that asks you to name a song, the character [that sang it] or maybe to unscramble the lyric. You might hear “Bibbidi-Bobbidi-Boo” [from the 1950 animated film Cinderella] and then you might hear something from Frozen II. That works because you often need a family — say, grandma, mom or dad, a child and an older brother — all playing together in order to get all the answers.

[embedded content]

How else are you optimizing voice activation for Disney?

Lieberman We work with our [DSP] partners to make sure that utterances that we are encouraging people to use bring up the results we want. We’ve also been very aggressive about putting a number of our classic titles into Amazon Prime Music, which has a limited overall catalog. We are aware that voice-activated devices are particularly popular with families and tend to sit in the common spaces of the home. And we wanted to make sure that our music was available widely so even folks who don’t subscribe to Amazon Music Unlimited are able to access something like Disney Hits. In partnering with the DSPs on initiatives like that, they are then more supportive broadly of the music across all platforms, and all boats rise. So we saw our Amazon Music Unlimited [streams] grow at an extreme rate concurrent with the Prime initiative. We were successful across the board.

As I mentioned earlier, we use tools like the Disney Hits Challenge to drive our music. There’s a skill where, if you get an answer wrong, you are prompted to the effect of, “Maybe you need to study up — listen to this Disney playlist.” I believe we were one of the first, if not the first, to have a skill-within-a-skill handoff where, within the skill, you could ask for one of our playlists and it would hand you off directly to that playlist instead of saying, “OK, ask me separately to play it.” That wasn’t initially connected on the back end, and it has driven hundreds of thousands of people to our playlist directly from the skill alone.

We also always try to do as much as we can with voices. Whenever we can, you’ll hear Mickey, Minnie or Donald cheering you on, or we’ll have takeovers from cast members in support of films that we’ve released, such as Aladdin or The Lion King. That keeps people engaged and gives [the playlist] a refreshing feel.

What is your ultimate goal: to drive streams or interest in the franchises from which the songs originate?

Lieberman A little of both. If you look at some of our playlists there are times that it’s not necessarily a straight children’s play. Guardians of the Galaxy is one of our top playlists, and we don’t control anything except for one or two songs on it and the score. But there was a value to developing it because it helped support this franchise. Our role as a division of the Walt Disney Company is to support each of the endeavors that the company is doing. When new music is recorded for the cantina at Star Wars: Galaxy’s Edge [at Disneyland Park and the Disneyland Resort], we create a playlist of it. We have playlists for everything from Little Fires Everywhere on Hulu to American Idol, but we also want to do it in a way that drives revenue for the company overall. Especially at a time like now, Disney Music is in a position to keep business on the healthier side.

Given that parents often take part in their children’s musical experiences — whether it’s listening to a playlist or seeing a live production — how much attention do you pay to not annoying those parents?

Linden A lot. One of our first live shows years ago was Yo Gabba Gabba!, which incorporated a number of components, including special guests. Biz Markie was in it, and it was proof of concept for us, where there were nostalgia elements and components that engaged parents. We continue to work hard to do that. We realize that the kids are our fans and consumers, but the parents are buying the tickets. And if parents have more than one child, it’s a great experience they’re likely to come back to with the next child. With Baby Shark [Live!] we had a lot of parents who said, “I liked it a lot more than I expected. It’s much better than I thought it was going to be.” We wondered whether it was a backhanded compliment or a reflection of other shows they attended, but you take it when you can get it.

Lieberman We know that the music is appealing to kids, but we look at it as music for the whole family. Of course, you’re going to have exceptions — Disney Junior is nursery rhymes and things that are focused on young children especially. But for the most part our goal is, we never want to annoy anybody. One of the reasons “Let It Go” is such an earworm is that it’s a great song that transcends age. What we find helps, too, is cross-generational appeal, where parents remember what their Disney music experience was when they were a kid. So seeing a similar experience through your children’s eyes does alleviate what might feel repetitious otherwise. Using our Disney Hits playlist as an example, we tend to have around 3 million unique listeners globally in a 30-day period, and they each listen to between 25 and 30 songs in a given session in a given month. That’s a really important metric for us. The other thing that we’ve done is come up with different versions of the songs for different moods. We have our Disney Piano collection in which the songs are played in simple, calming piano arrangements. We include many of those in our Lullaby playlist. We also offer classical versions and are working on a “peaceful guitar” series as well, which will feature simple acoustic guitar versions of our songs.

Jonathan, given that parents are buying tickets to Round Room’s live shows and subscribing to the streaming services that play Disney’s music, figuring out your audience can’t be easy. What data are you using to determine what works?

Linden The world has changed a lot over the last number of years. When we did Yo Gabba Gabba!, it was on Nickelodeon Jr. If you wanted to break a major preschool kids’ brand back then, it had to be through broadcast or cable TV. Today, brands are coming from lots of different platforms and places — YouTube, streaming services and social media — and determining what would work in our case can be challenging. So we’ve got a sophisticated approach of looking at things. Some people were surprised that we chose to develop a production around Blippi, which began on YouTube, but our analysis showed that that the character had really penetrated [the demographic] and that its followers were strong and active [on social media]. [The character] Baby Shark may have seemed like a logical choice, but it didn’t have a TV show or a sophisticated consumer packaged goods follow-up. It was the first tour of a preschool brand that doesn’t have a broadcast TV show.

“Baby Shark” was also a single song that you developed into a 20-number show. What data made you say, “We can expand this into a live production”?

Linden We knew how popular it was on YouTube, we knew the followers in relation to social media channels, and we could tell how it was penetrating a space beyond just kids — you could see it in the stands when the Washington Nationals played the World Series. We also knew that SmartStudy, which manages the Pinkfong brand, had a huge catalog of music. While the song “Baby Shark” is the star of the show, there’s a lot of other exciting music they had in their catalog that we felt confident we could turn into a dynamic show. To some degree it was speculative and risky, but to us it was exciting because it added an element of creativity. Maybe that’s why some of the parents told me it was better than they expected.

[embedded content]

Karen, what kind of data are you looking at?

Lieberman As much as we can get our hands on. We spend a lot of time looking at the streaming data for our music and catalog across all platforms. We look at trends. The Disney Piano series gets almost twice as many streams per listener as anything else we do because people are setting it and forgetting it — over 40 streams per listener on average for the last 30 days, according to data from our partners, compared to Disney Hits, which has 26 streams per listener for the same period. It’s calming, and they have it on in the background while they are working, studying or cleaning.

We look at how songs perform in context of one another. For instance, is it too jarring to go from something super classic to something newer?

We also pay a lot of attention to social activity. A year or two ago, we noticed a rebirth of interest in Hannah Montana, Sonny With a Chance and other classic Disney Channel shows. As the kids who were fans of these came to be a bit older, that was their nostalgia play. So, we leaned into that and launched a Disney Class Reunion playlist across all of our partners. It features music from these properties and that era overall.

We’re also taking cues from what is working on other Disney outlets. That includes broadcast, Disney+ and the parks, when they are open. Although actual streaming activity on Disney+ is held very close to the vest, we pay a lot of attention to the trending page there. If we notice Mickey Mouse Clubhouse is No. 3, we will focus on that. For instance, we’ll make sure tracks from it are featured prominently on pertinent playlists. In some cases, we’ll schedule additional social media support and advertising to take it even further. So much of it is a catalog play for us, especially now, but we want to make sure that we surface the things that people are looking for at any given time.

Jonathan, you worked with The Rolling Stones and Barbra Streisand. What’s similar and dissimilar about those shows compared to Baby Shark or Blippi?

Linden My partner Stephen Shaw and I worked at Concert Productions International and then Live Nation. We had a lot of experience with some of the major concert experiences, and first at CPI and, later, Live Nation, we were tasked with running other ticketed events — kids and family shows, Broadway shows, traveling exhibitions. As Live Nation consolidated the concert business, which made it trickier for independent promoters [to do business], we saw opportunity in the kids and family space. Live Nation and the major promoters weren’t really in that business. It was an area with great opportunity and growth potential, and in 2016 we created Round Room to focus on those areas of the business.

We’re applying the lessons we learned in the concert space to the kids and family space. Obviously, the size and scope are different. A major act can play in an arena or a stadium — you’re talking about 25,000 up to 50,000 ticket holders. The kid shows are usually in the 2,500 range, with bigger shows 4,000 to 5,000.

But there’s a lot to be applied from the concert world that works. We’ve brought more technology to the experience. We were, I think, the first to do a full LED wall, which is a common component in a concert tour. We turn the VIP experience into more than just a lanyard. You feel like you are backstage, although there is one difference. When we did VIP experiences with The Rolling Stones, there were individual band members, who shall remain nameless, who from time to time would decide to not show up. Whereas, with the shows we do today, the costumed characters always come to the VIP.

Jonathan, your company found Blippi on YouTube. What do you both think about YouTube and TikTok as breeding grounds for new intellectual property?

Linden YouTube, when it first launched, was all kinds of content that was hard to navigate. Now it’s a lot more sophisticated, and for some of the preschool brands on it, the way they navigate their subscribers is getting closer to broadcast TV. You can follow the streams and the subscribers and how active they are. It has been interesting for us to find stars like Blippi that way, but I think stars are going to come from a variety of different sources. We deal with a lot of the agencies that represent YouTube stars, which has become its own category, and some of those agencies are picking up TikTok talent. We’ve had some initial conversations. Some of them are natural talents, and TikTok is simply the platform they’ve come through. And every once in a while you talk to someone where you’re not quite sure how they became so followed. They’re very unconventional, and determining the specific skill set that could be exploited onstage is a little tricky.

Lieberman We have a tremendously successful channel with our DisneyMusicVEVO channel. It crossed 19 million subscribers in the last 24 hours. We grow at a clip of over 100,000 subscribers a week. As of a couple of weeks ago, we were well over 12 billion views on the channel. It’s one of the top 100 most-viewed channels across YouTube. We cross-pollinate there. We have Descendants videos to musical moments from Frozen II and Moana; lyric videos; and singalongs. And then there’s a backfill happening of catalog that was out before YouTube was really a thing. We’ve gone back and put in some of the classic High School Musical videos in there, for example.

Why do you think the Descendants franchise has been such a success for Disney?

Lieberman That was a unique one for us. When the first Descendants film came out, we partnered with VEVO, and they let us put what we call “lift” videos, which are basically lifts of musical moments from the film, as individual music videos. That worked extremely well, and I think it reverberated back-and-forth: The soundtrack debuted at No. 1, and the movie was the top TV movie that year. Since then, Descendants 2 and 3 and other ancillary pieces of the franchise have come out and generated over 3 billion views on our VEVO channel.

Another film that has performed extremely well is Moana. “How Far I’ll Go” is our top video, with more than 750 million views. That’s for a single video. We’ve just added four or five singalong versions from Moana that we had not released previously, and they are all performing very well.

We spend a lot of time maintaining the community there, working with VEVO to make sure our music is marketed well there, and it has been a major success. We anticipate that we’re going to hit 20 million subscribers in the next month or two.

What’s your perspective on TikTok?

Lieberman What I will tell you is we are watching it closely. We’re hyper-aware of its popularity and the use of our music that is happening on the platform, but I’m not really at liberty to discuss much more than that right now in terms of our approach.

Jonathan, in the wake of Round Room’s success with Baby Shark Live!, do you find that you are coming up against more competition attempting to mine YouTube for touring productions?

Linden It goes both ways. Inevitably, competitors see it as a landscape to find talent, but by virtue of being the first our phone has been ringing. But to your point, I think that YouTube and TikTok will turn out touring talent, for sure.

The mainstream popularity of hip-hop is trickling into children’s music through Kidz Bop and Rockabye Baby, which just released a Wu-Tang Clan collection. How does hip-hop figure into your business plans?

Lieberman It’s not really something we have a focus on. There are elements of that music incorporated into some of our music. The Descendants movies have a couple of songs where characters are rapping, so to speak, but it’s more kid-friendly. Hip-hop is not really something that we have a focus on. We have a different lane.

Linden [Entertainment] One’s recorded-music [division] label has a lot of hip-hop [including Death Row Records], and we’ve had a lot of different conversations there. I’m not sure it’s translating today into what we’re doing, but we would love to figure it out.

You each represent some of the most popular children’s characters in the world. Are there any that are not controlled by your respective companies where you think the people behind them are doing a good job?

Linden I’m Canadian, and there’s a toy company out of Canada called Spin Master. It competes with Hasbro. We knew them when they were the toy provider for Yo Gabba Gabba! They started to create some of their own content, such as PAW Patrol. There are a number of companies like that that are becoming more diversified, and it pushes some of the bigger players to be more innovative.

Lieberman The one that I’m most taken with is Lego. Their approach is, first of all, extremely positive; they’ve got something for all ages; they foster this ability for kids to build and grow and be creative, but they do it in a way that incorporates familiar characters, third-party brands and franchises into what they do. And, this is just me, but I think they’ve really brought a lot to the table just in the past year in terms of their take on recycling.

Is there an average shelf life to a successful children’s franchise?

Lieberman I don’t think there are any hard and fast rules. There’s really nothing that goes in the vaults anymore, so that’s not really applicable, but there are different ways to continue bringing those characters to new audiences. A great example is the animated movie Tangled, which was released [about three years] before Frozen. Frozen ended up exceeding it, but Tangled was certainly a success. And a couple of years ago, an animated Tangled series launched on Disney Channel. It has performed extremely well, both critically and audiencewise. Many kids discovered the Tangled characters through the series and then watched the movie. Similarly, before the live-action Lion King, Disney launched a series on its channels called The Lion Guard, which was about a secondary character from the original animated film. That performed extremely well, and I can tell you from my nephews and niece that was their introduction to The Lion King. If I held up a picture of Simba and asked them, “Who is this?,” they’d say, “Kion,” because that’s who it looked like. It’s a different way to cross-appeal and just keep it going.

Linden I was looking around as Karen said that because I’m in the kids’ toy room right now where there is a Bunga somewhere — he’s one of the guys from The Lion Guard. To tie it back to music, there are bands like The Rolling Stones that stay relevant and popular for years. Then there are bands that have a popular album and then you don’t see them much and they resurface playing bars in Las Vegas. I can’t put my finger on a preschool brand that’s playing a bar in Vegas, but inevitably there are lots of kids’ brands that have a successful season and don’t stick around. The magic is, how do you keep a brand relevant?

This interview has been edited and condensed

Additional reporting by Steve Knopper