It’s become a cliché, even for post-Baby Boomers, to look back wistfully on the early ’70s as some kind of untouchable golden age for popular music. But when you survey all the era’s best albums in list form, it’s hard not to trust that instinct.

I mean…holy shit.

In 1971, the psychedelic era hadn’t completely wilted; prog was nearing its popularity apex; Motown was still a revolutionizing soul music; the folk-rock movement was in full flight. The possibilities were limitless.

You know it’s a banner year when 50 albums don’t begin to scratch the surface — when both John Lennon and Paul McCartney release definitive LPs and neither make the top 10. Was 1971 the greatest album year ever? We’ll save that debate for another time (or maybe another list).

For now, we present 50 stone-cold classics from a most malleable music year. – Ryan Reed

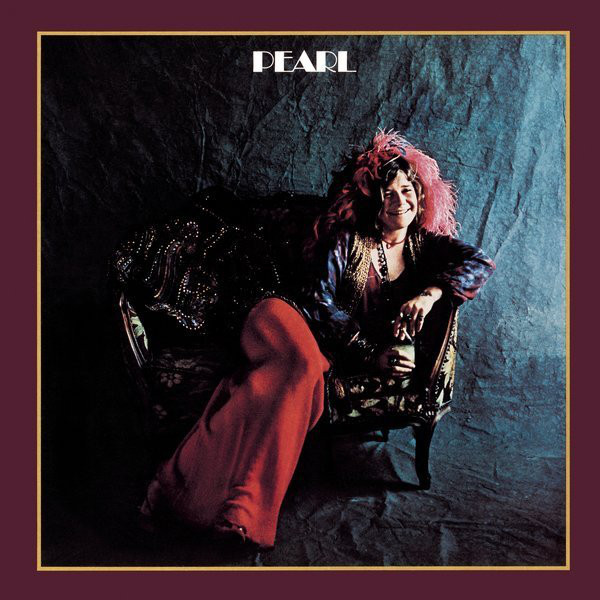

50. Janis Joplin – Pearl

Even beyond the grave, the feisty Janis Joplin refused to let her presence diminish. Pearl, the posthumous album released three months after her 1970 death, highlighted her evolution into a more mature sound. Here, she was no longer confined to the psychedelic band Big Brother and the Holding Company (but let’s be honest, can one really hide an enormous voice like hers?), and she was armed with songs sturdier than those on her 1969 debut. Bluesy, polished opener “Move Over” should have been a radio hit; “Cry Baby,” soaked in despair, is now a soul-blues standard; and her cover of Kris Kristofferson’s “Me and Bobby McGee” is an exciting twist on classic country. With Pearl, lovingly titled after her nickname, Joplin was more than just a 27 Club statistic — she became a singer of singular grandeur. – Bianca Gracie

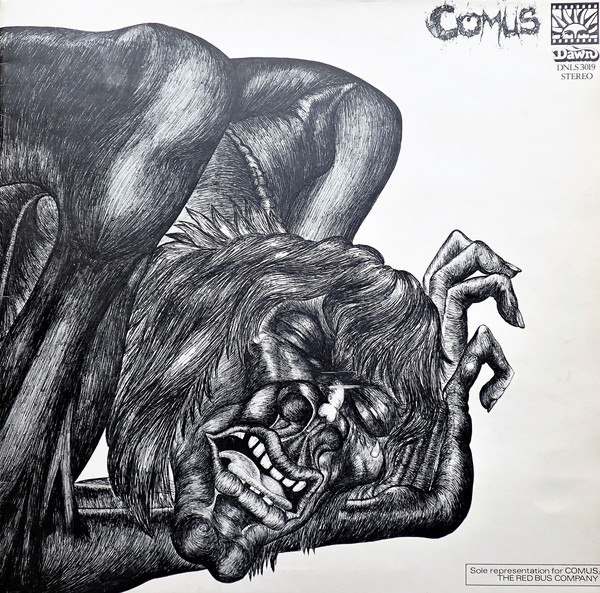

49. Comus – First Utterance

This prog-folk gem, equally zany and unnerving, is not for the faint of heart. While new listeners may detect hints of King Crimson, Frank Zappa and early Pink Floyd on Comus’ debut LP, the British band occupied their own unique space on First Utterance. The album meanders from unintelligible, vibrato-heavy bellowing to viciously delivered refrains to disturbing raconteur tales (exploring subjects like hangings and mental illness). (Singer-guitarist Roger Wootton once described “Drip Drip” as a “psycho horror story partly inspired by horror films of the time,” noting, “Many writers invent these extreme characters on the edge of the human condition.”) It’s all bottled in experimental ballads both erratic in structure and instrumental technique, blending dissonant violin, baroque guitar and faery flutes — soundscapes that alternate between ethereal and ominous, often multiple times in a single song. – Logan Blake

48. Serge Gainsbourg – Histoire de Melody Nelson

Serge Gainsbourg courted controversy with Histoire de Melody Nelson, a concept album about a middle-aged man seducing a young girl before her inexplicable death. (The latter character was voiced by his then-paramour Jane Birkin, who also posed topless on the cover.) The songwriter, assisted by arranger Jean-Claude Vannier, created a dark and twisty world of jagged jazz guitar lines, embellished string sections and breathy spoken-word — the kind of Gaelic cool that still sounds daring, even to high school French flunkies. It’s no wonder artists from Beck to Jarvis Cocker to Air still borrow the poet’s singular, swaggering style. While attempting to raise eyebrows, Gainsbourg succeeded in raising the bar. – Laura Studarus

47. Carly Simon – Anticipation

In 1971, Carly Simon quickly became a pop superstar: winning the Grammy Award for Best New Artist and releasing her first two albums, Carly Simon followed by Anticipation. The latter’s title track — reportedly scribbled in the car before her date with Cat Stevens — became a massive radio single. But beneath the sheen of sudden fame, Simon’s early work reveals how her rich interior world, filled with melancholy and childhood nostalgia, informs her lyrics. On “Legend in Your Own Time,” for example, Simon sings about a boy who fulfills his dream of becoming a singer, only to realize the price of connection is a lifetime of loneliness. With “The Girl You Think You See,” Simon becomes a proto-Morrissey — debasing herself in the name of love while a cheerful melody plays on: “Whoever you want is exactly who / I’m more than willing to be.” It took decades for Simon’s songwriting skills to be properly recognized. But Anticipation’s relevance lives on in the music of her fans like Tori Amos, the Chicks’ Natalie Maines, and Taylor Swift — to name a few. – Sarah Grant

46. Jan Dukes de Grey – Mice and Rats in the Loft

Jan Dukes de Grey didn’t stand a chance at a long career — even during this wildly freewheeling year when epic-length songs and non-rock instrumentation were badges of honor, not crutches of the soon-to-be-extinct. But the British band’s cult classic second LP epitomizes the musical freedom of 1971. Mice and Rats in the Loft is a batshit-crazy masterpiece, with multi-instrumentalists Michael Bairstow and Derek Noy (accompanied by drummer Dennis Conlan) cramming every imaginable sonic shift into three restless tracks. The most famous is the 19-minute opener “Sun Symphonica,” which morphs from flowery post-psychedelia to sax-driven prog to soothing chamber-pop orchestrations. – Ryan Reed

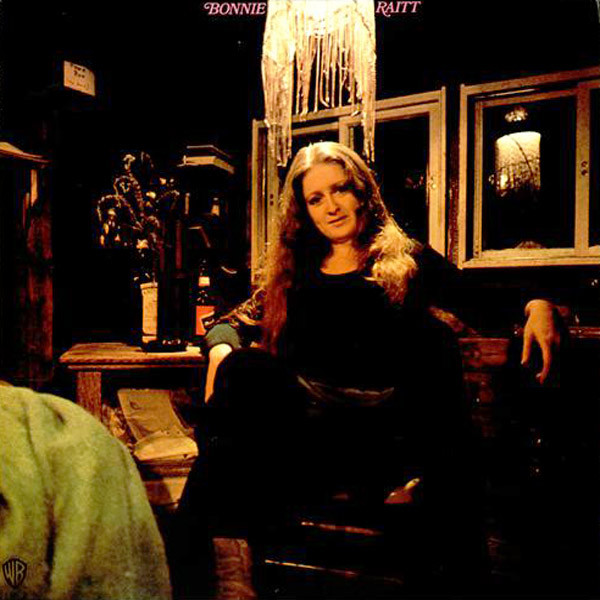

45. Bonnie Raitt – Bonnie Raitt

At just 22, Bonnie Raitt’s self-titled debut record made her a wunderkind of the early ‘70s folk scene. Though the album didn’t sell, critics marveled at her playing slide guitar with the ease of a pro, articulating between different hues of blues, folk, jazz and soul. The album covers an eclectic swathe of musical history, from old blues and jazz standards by Tommy Johnson, Robert Johnson and Buddy Johnson to Motown to Buffalo Springfield. But Raitt’s true north star was Sippie Wallace, a Chicago blues-jazz singer from the 1920s. Raitt was a student of Wallace’s career, including her 1966 comeback album. So Raitt bookended her debut LP with rollicking renditions of two Wallace songs (“Mighty Tight Woman” and “Women Be Wise”) — a fitting tribute to the artist who inspired her to sing in the first place. – S.G.

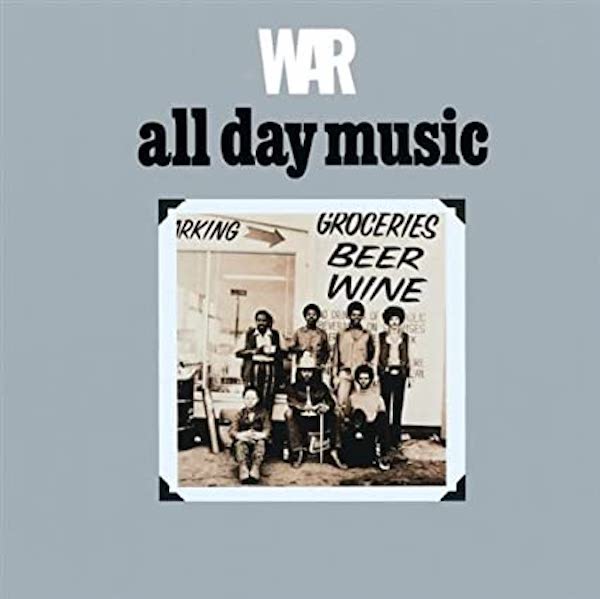

44. War – All Day Music

War’s fourth album — and second without Animals frontman Eric Burdon — was a breakthrough for the funk-rock septet, kicking off a string of gold albums thanks to the massive groove of the single “Slippin’ Into Darkness.” But the album’s centerpiece, the seven-minute “That’s What Love Will Do,” is a cinematic ballad, anchored by an insistent kick drum pattern and showcasing Charles Miller on flute and saxophone. All Day Music cemented the omnivorous Long Beach band’s kitchen-sink aesthetic, featuring Lee Oskar’s twangy harmonica leads, conga-driven funk and the guitar-heavy live cut “Baby Brother.” – Al Shipley

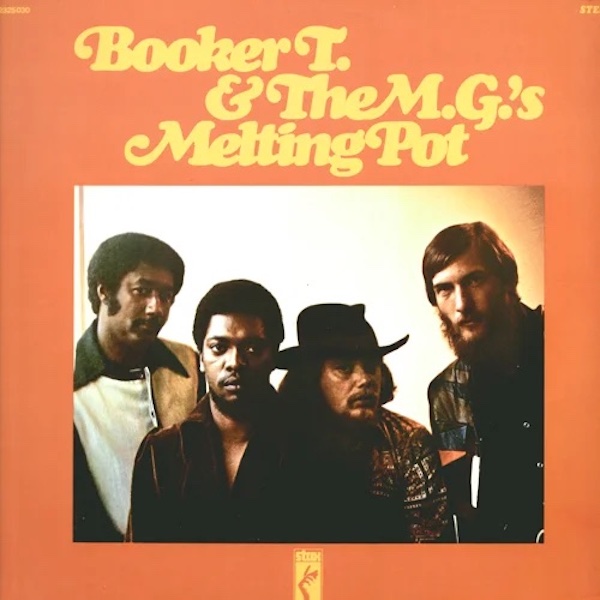

43. Booker T & The M.G.’s – Melting Pot

Melting Pot is the final studio album from the original M.G.’s: Booker T. Jones, Al Jackson and those two underrated fellas from the Blues Brothers, Steve Cropper and Donald “Duck” Dunn. The interracial quartet, and one-time house band for Stax Records, went out with a bang: Their eight, often extended jams meld jazz, rock and soul, with Cropper getting all funky on the title track. These grooves have endured through sampling, used by everyone from hip-hop great Big Daddy Kane to R&B-pop act New Edition. – Jason Stahl

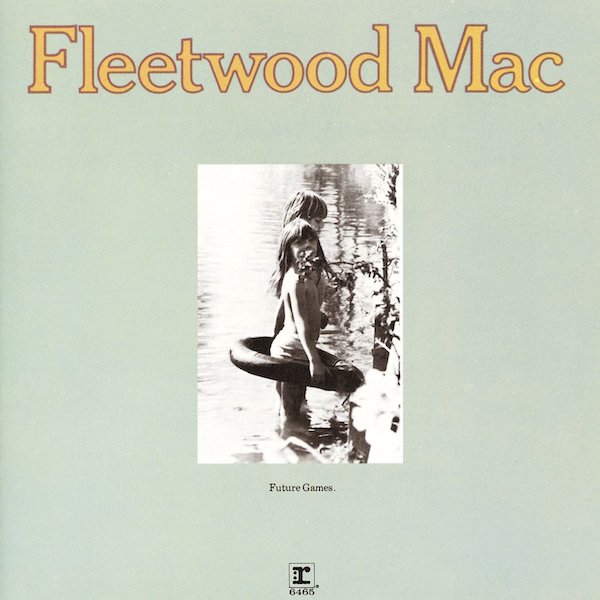

42. Fleetwood Mac – Future Games

Future Games marked a pivotal turning point for Fleetwood Mac: It was their first album with singer-guitarist Bob Welch and vocalist-keyboardist Christine McVie, who helped push the band’s previously bluesy sound into folk, soul, pop and psych. (McVie already had significant ties to the group, having married bassist John McVie in 1970, painted the cover of that year’s Kiln House and contributed uncredited material to that album.) Future Games is anchored by standout performances from both the new recruits: On his title track, Welch pours out dreamy electric guitar for eight minutes, that vibe lingering into guitarist Danny Kirwan’s “Sands of Time.” And McVie brings a similar lightness to closer “Show Me a Smile,” a tender ballad she nails with ease. – Tomas Miriti Pacheco and R.R.

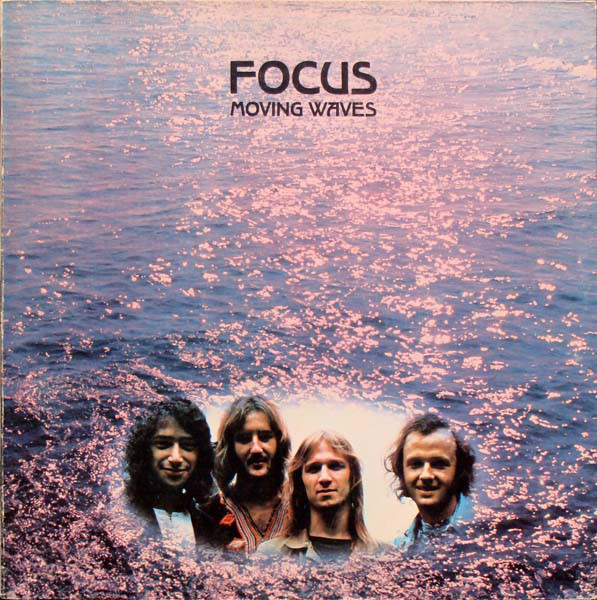

41. Focus – Focus II (Moving Waves)

In 1971, if you wrote a hard rock song filled with yodeling, Appalachian beatboxing, classical Hammond organ, jazzy drum solos and full-blown shrieking, you had no reason to assume it wouldn’t be a hit. “Hocus Pocus,” which peaked at No. 9 on the Billboard Hot 100, is the obvious centerpiece from Focus’ second LP. But the Dutch quartet were far from a novelty act, stretching out into oceanic guitar interludes (“Le Clochard”), flute-heavy balladry (“Janis”) and winding prog (the 23-minute “Eruption”). Come for the yodeling, stay for the…everything. – R.R.

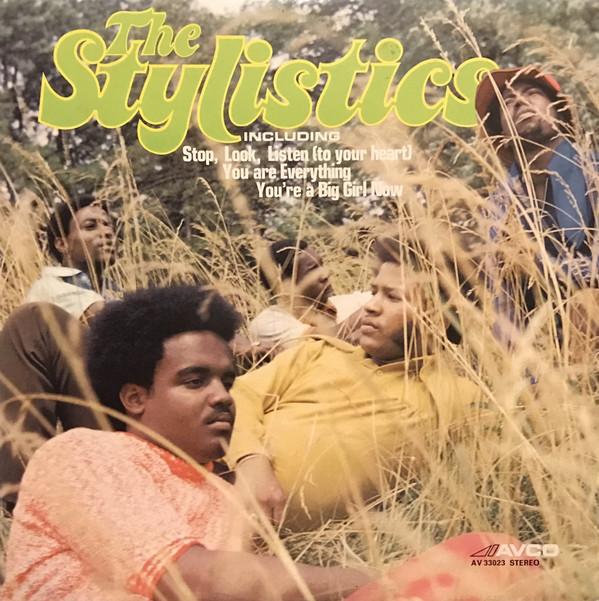

40. The Stylistics – The Stylistics

Any pop star with a hit love ballad after 1980 — Whitney to Mariah to Timberlake to Usher to Bruno — owes a major debt of gratitude to Philadelphia soul music. And no group epitomized that diaphanous era quite like the Stylistics. Led by tenor Russell Thompkins, Jr., the group’s debut was an overnight success, scoring a handful of hits on Billboard’s R&B, Pop and Adult Contemporary charts. Behind the velvet curtain, The Stylistics forged the brief but prolific songwriting duo of Thom Bell and Linda Creed, who co-wrote legendary ballads like “Stop, Look, Listen (to Your Heart),” “Betcha By Golly, Wow” and “You Are Everything.” At the time, Bell/Creed were an unlikely pair: He was a Grammy-nominated producer nicknamed “the Black Burt Bacharach,” and she was a white singer-lyricist who broke through with a Dusty Springfield hit. As different as they were, Bell and Creed both understood the strange magic of Philly soul — and with the Stylistics as their canvas, they created some of the most unfathomably romantic songs of all time. – S.G.

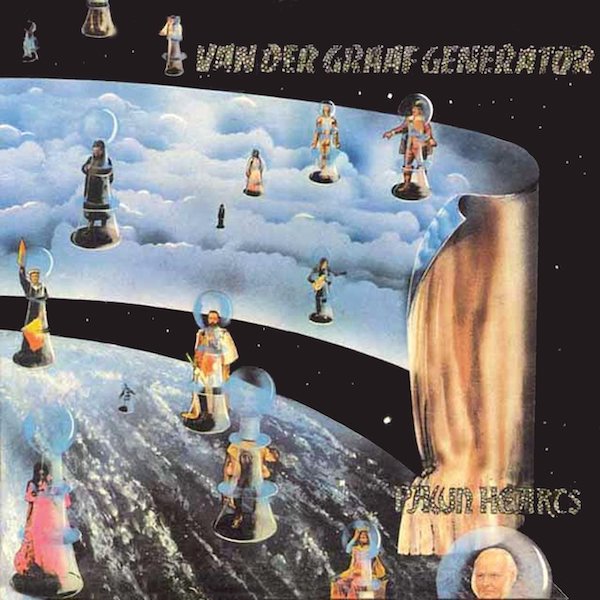

39. Van Der Graaf Generator – Pawn Hearts

“Part of the drive was just for it to be visceral, immediate, active,” Peter Hammill told NPR in 2008, describing Van Der Graaf Generator’s abrasive, aggressive form of prog-rock. “And actually, I think, yeah, we picked up quite lot of audience at that time who wouldn’t have remotely dreamed of going to see ELP or Yes, for instance.” Pawn Hearts, the British band’s fourth LP, epitomizes that blend of top-shelf chops and punk-friendly energy. Hammill sings every one of these songs, including the 23-minute epic “A Plague of Lighthouse Keepers,” like a deranged Shakespearian actor selling his performance for the back row. And the band’s mish-mashed sound — jazzy drums, dramatic piano, harsh organs, menacing woodwinds — is unlike any other under the prog umbrella. – R.R.

38. Elton John – Madman Across the Water

Elton John’s grandly arranged fourth studio LP — his third overall ‘71 release, following a soundtrack for the U.K. teen film Friends and his first live album, 11-17-70 — is known for the immensity of its first two tracks: catalog staples “Tiny Dancer” and “Levon.” Kudos to British composer Paul Buckmaster, whose definitive string arrangements provided the ambitious sweep that informed John’s subsequent releases, namely his 1973 masterstroke, Goodbye Yellow Brick Road. Brooding and bold, Madman was a stark departure from its predecessor, the 1970 country concept album Tumbleweed Connection, and didn’t sell particularly well in the U.K., reaching only No. 41. (It hit No. 8 on Billboard’s U.S. Pop Albums chart). Fifty years later, casual fans remember only the mammoth singles, though John still employs the booming, seven-minute opus “Indian Sunset” as a concert showstopper. – Bobby Olivier

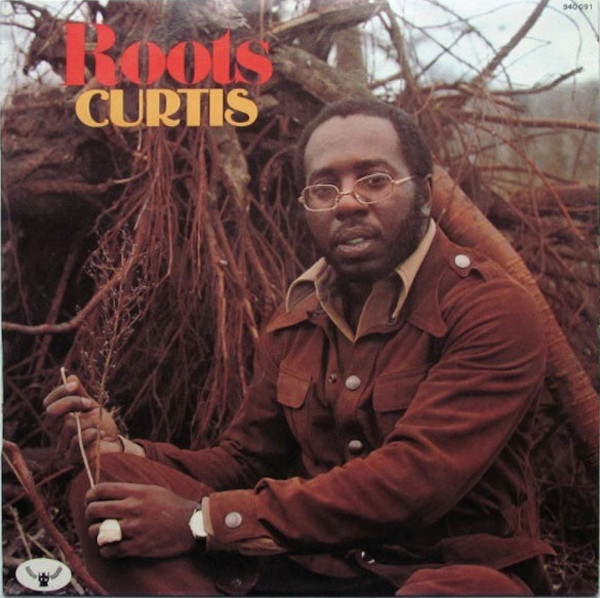

37. Curtis Mayfield – Roots

Roots, Curtis Mayfield’s 1971 opus, is a sprawling soul soundscape, filled with joyous melodies and effortless grooves. Its lengthy anthems are cries for peace and unity; his extraordinary, almost weepy singing accents the urgency of these pleas. Mixed in with these calls to action are textured love songs layered with yelps, shouts and groaning horns. As a whole, the album demands togetherness — Mayfield reaches out sincerely to his audience, leaving every emotion on wax. – T.M.P.

36. Emerson, Lake & Palmer – Tarkus

Let’s pause for a second and recognize the absurdity that both these statements are true: ELP’s second LP opened with a wailing, 21-minute epic more monstrous than the armadillo tank on the cover, and the record somehow peaked at No. 9 on the Billboard 200. Tarkus’ title piece would be just as powerful at half the runtime (and half the Hammond organ solos), but it’s still among the most ambitious rock songs of 1971 — splitting the difference between the tightly composed Yes epic “Close to the Edge” and Genesis’ manically sprawling “Supper’s Ready,” both of which arrived the following year. “Tarkus” inevitably overshadows the rest of the album, but there are some treasures on the back half, including the snappy, psych-saloon fusion of “Bitches Crystal.” – R.R.

35. Gong – Camembert Electrique

It’s sloppier and more abrasive than their classic Radio Gnome Invisible trilogy, but Gong’s second album fully cemented their psych-prog wackiness. Bandleader Daevid Allen’s knotty songs wander through warped vocal hooks, jazz-rock riffs (accentuated by the woodwinds of Didier Malherbe) and the orgasmic “space whispers” of Gilli Smyth. The best restlessly browse through all those vibes: “You Can’t Kill Me” almost recalls King Crimson’s “21st Century Schizoid Man” with its hybrid of metallic, chromatic heaviness and jazzy chops. But it’s hard to imagine Greg Lake singing a line as spacey as “You’re really only me if you’d only remember.” – R.R.

34. Santana – Santana (Santana III)

Neal Schon flourished as an arena rock God in Journey, but he began his career as a 17-year-old guitar wizard on Santana’s third studio LP. His exuberant playing nearly matches maestro Carlos Santana throughout the album, pushing the septet’s Latin-rock grooves into funkier, more explosive territory. The radio staple is their modest hit “No One to Depend On,” the most streamlined tune of the bunch. But Santana’s percussive, wall-to-wall attack reaches ecstatic muso heights on “Toussaint L’Overture” and “Everybody’s Everything,” the latter backed by the Tower of Power horn section. – R.R.

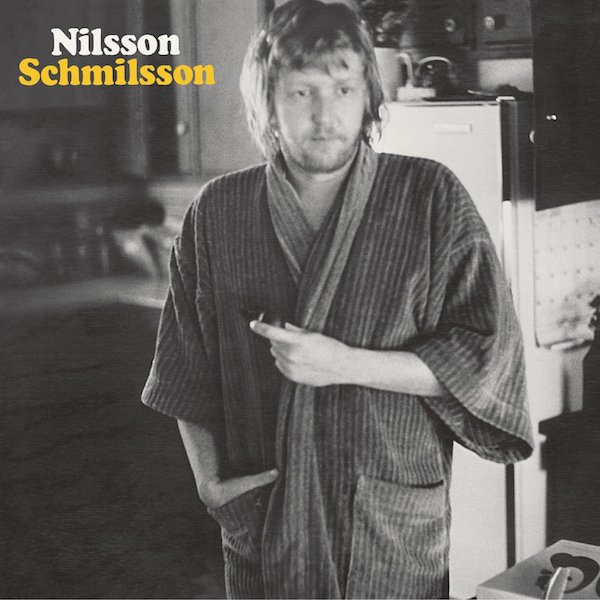

33. Harry Nilsson – Nilsson Schmilsson

Harry Nilsson deserves to be as well known as Randy Newman, another insanely talented writer of poignant, often quirky pop. And newcomers should start with Nilsson Schmilsson, his seventh and most famous LP. Opener “Gotta Get Up” is now familiar as an endlessly looping tune from the 2019 series Russian Doll, while the calypso-tinged hit “Coconut” remains a delightful slice of near-novelty. The heartrending ballad “Without You” manages to induce chills while avoiding sappiness — a welcome hallmark of Nilsson’s most timeless compositions. But the LP’s standout is the frenetic seven-minute version of “Jump Into the Fire,” discovered by many thanks to a crucial scene in Goodfellas (and later covered by late Nilsson fan Chris Cornell). – Katherine Turman

32. Alice Coltrane – Journey In Satchidananda

The title of Alice Coltrane’s fourth solo LP nods to her spiritual advisor Swami Satchidananda. It’s a fitting allusion: The album, splitting the difference between modal jazz meditation and Eastern drone, washes over like a whisper from the divine. On the opening title track, Coltrane’s harp ripples out, dream sequence style, over a grainy tanpura, as Pharaoh Sanders gently — then dizzyingly — glides around his soprano sax in a feat of superhuman breath control. The centerpiece, “Something About John Coltrane,” is named after another crucial figure, her late husband. The piece rattles and stammers and prods, with piano and sax and bells blissfully teetering between cacophony and cosmic melody. – R.R.

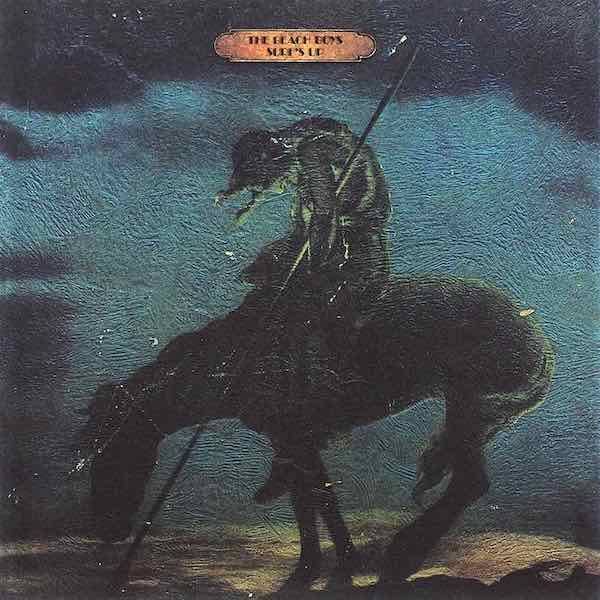

31. The Beach Boys – Surf’s Up

Though they hit their creative peak half a decade earlier, the Beach Boys still had some interesting songs left in their arsenal. With Brian Wilson less involved than on 1970’s Sunflower, the group became even more democratic on the kaleidoscopic Surf’s Up: Even Carl Wilson, an infrequent writer, was more creatively active, co-penning the synth-heavy jazz-rocker “Feel Flows” and intricate psych-pop tune “Long Promised Road.” Even with an edgier, more layered sound, the band’s 17th album was still catchy as hell — though not as widely accessible as their previous records. Songs like “Student Demonstration Time” (a take on “Riot in Cell Block Number 9″), “A Day in the Life of a Tree” and “Don’t Go Near the Water” added more of a social conscience. And the title track — not a song about surfing — is both the LP’s highlight and a majestic leftover from Brian’s then-unfinished opus, SMiLE. Surf’s Up’s progressive pop style resulted in one of their last great LPs. – Daniel Kohn