“The Bo Diddley Beat.” Oh, you’ve heard it many, many times. Beyond Bo’s introduction of the style, it’s been used in such memorable hits as “Magic Bus” by The Who, “Faith” by George Michael, “American Girl” by Tom Petty, “Mr. Brownstone” by Guns N’ Roses, “Desire” by U2, “Who Do You Love” by George Thorogood and the Delaware Destroyers, and “Black Horse and the Cherry Tree” by KT Tunstall, among others.

A clear rendition of what this beat sounds like is the drum intro to “Rosanna” by Toto. It’s popular and catchy and makes you want to get up and dance. Bo used it on his self-titled album on the song “Bo Diddley.” The album is otherwise a solid blues effort. I was surprised to read “American Girl” as having this same percussive beat because it didn’t strike me as being similar to the others but check out the drum intro and you’ll hear it clearly.

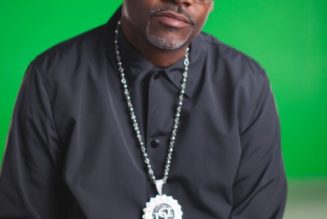

The term “Bo Diddley Beat” was coined by Mr. Diddley himself, though his real name was Elias Otha Bates. He later took the surname “McDaniel” and then went with the nickname “Bo.” Though theories vary, he apparently used the stage name of “Diddley” based on an instrument called a “diddley bow”, a one-stringed West African guitar. Still, others say it was just a catchy name given to him when he first started to perform in local neighborhoods.

The pattern typically involves a two-measure syncopation which in the song “Bo Diddley” used the combination of guitar and maracas. It’s very similar to the southern technique of ham-boning and is meant to allow the performer to create unique rhythms using the slapping of body parts (thighs, arms, chest), clapping, and making guttural noises. There’s a similar African American slapping rhythm that’s called “Pattin’ Juba.” It can even be heard in the vaudeville-inspired “shave and a haircut, two bits” knocking pattern that consists of three strokes, rest, and two strokes. Other origins include the Tresillo style (duple-pulse rhythmic cell) used in Cuban, Latin American, and Caribbean music.

Musically speaking it’s known as a simple 3-over-2 clave rhythm played in 4/4 time, often played in both one and two-bar phrases. It’s commonly heard as “bump…bump…bump…BA-dump”. Bo suggested that he didn’t know the African roots of the beat, but instead learned it via the upbeat music he heard in church songs as a child. Once you learn to recognize it, you’ll find it used very frequently, even if not as obvious as in the intros to “I Want Candy” and “Rosanna.”

Historically, a style of music called the “Juba Dance” originated in African American slave culture in the American South. Slaves were often not allowed to own or construct percussive musical instruments and so they used their bodies to make rhythmic sounds. Actual playing of instruments was mostly only allowed during Sunday church services and this style of music and its beat was incorporated into a variety of religious songs. Listen to the classic “Wade in the Water” as performed by Ella Jenkins on the album African American Folk Rhythms as an example of religious music that carried a similar beat.

Often songs such as “Wade in the Water” also were to communicate across slave groups with calls on how to behave, what to expect, and what to do in various scenarios. The songs had to be memorable and catchy so that they could be repeated without being written down. Since Africa is a continent made up of countries that have a variety of languages and musical styles, these would be merged and combined to form new sounds. Add that many of these laborers also came from the Caribbean and South America and you end up with best-of-the-best in terms of rhythm and musical styles from those regions.

Coming back to modern times, many of these original African musical tropes translated to not only the Bo Diddley beat, but musical styles such as ragtime, the backbeat, the shuffle, and the boogaloo. The cadence was also picked up by Johnny Otis, with his release of the classic “Willie and the Hand Jive.” In this case, the Bo Diddley beat was combined with ham-boning (clapping and chest-patting). It was a hit in 1954, which lead to the associated dance craze, and was later covered by Eric Clapton in 1974. It can also be heard in a modern implementation as part of the hand-jive segment in the movie Grease performed by Sha Na Na. And the style was basically lifted by the Rolling Stones on their release “Not Fade Away” which was originally written and recorded by Buddy Holly and the Crickets in 1957.

The Bo Diddley beat continues to live on in modern music because the syncopation requires some thought when compared to a basic four-on-the-floor disco and rock beat. It’s interesting and catchy and lends itself to a variety of musical styles. It has a stark origin in Afro-South American-Cuban music that appeared across slave plantations which reminds us that styles from across the world and across time continue to influence modern music. Next time you find yourself unable to sit still during a song, listen carefully and you might hear some variation of the Bo Diddley beat influencing your need to get up and boogie.

-Will Wills

Photo: Bo Diddley, 1957 (public domain)