Texas’ deep freeze was the latest warning that extreme weather events threaten to derail efforts to clean up the most toxic sites in the US. In a worst-case scenario, a natural disaster can unleash buried toxic substances. But even minimal damage or the mere threat of a storm can stop or slow cleanup efforts.

That vulnerability could become a bigger problem as climate change brings about more weather-related disasters. For years, experts have pushed the Environmental Protection Agency to prepare for the onslaught.

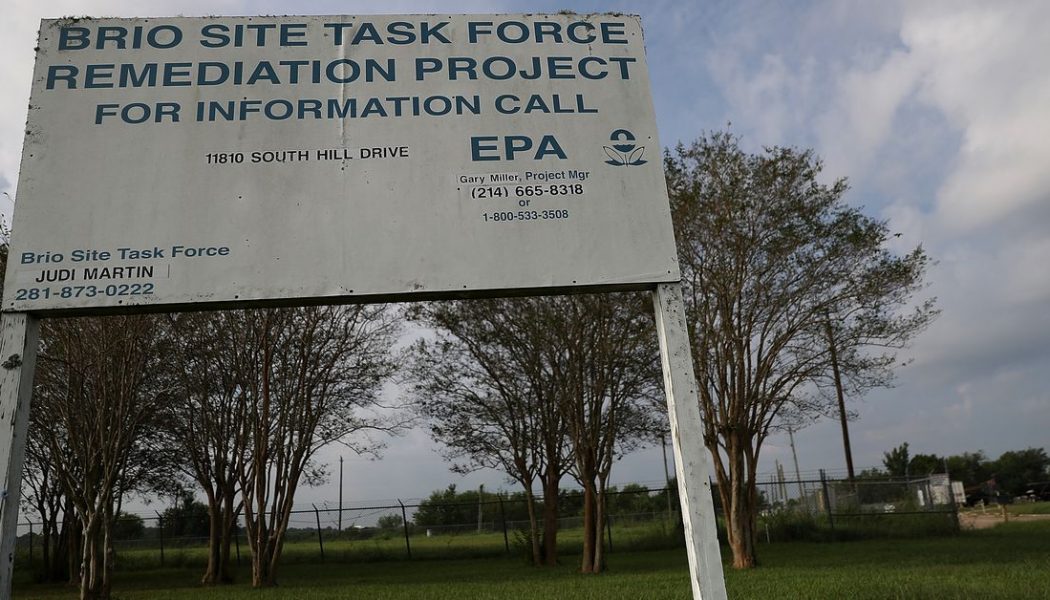

“We have over two dozen Superfund sites here in our county, and we are one of the most threatened coasts in the world by natural forces,” says Jackie Young-Medcalf, executive director of the Houston-based nonprofit Texas Health and Environment Alliance. “As long as the waste remains in place … It’s at risk for impacts from Mother Nature.”

Efforts to control hazards at some toxic Superfund sites in Texas temporarily halted as a result of the deep freeze that battered the state’s infrastructure in February. Superfund sites are places so polluted that they were placed on a National Priorities List for cleanup. Several of these sites lost power or preemptively stopped operations during the freeze, according to the Environmental Protection Agency. At least four sites sustained minor damage like cracked pipes.

After winter storms knocked out power and water systems, the EPA assessed 16 Superfund sites in Texas, Arkansas, and Louisiana for problems. The damage it found didn’t lead to any contaminants being released, the EPA told The Verge in an email.

But the storms did manage to freeze some Superfund operations, at least temporarily. One of the Superfund sites that Young-Medcalf’s group has monitored over the years, the Jones Road Groundwater Plume in Harris County, was damaged during the recent cold snap. The EPA found leaking valves and ruptured pipes and fittings at the site following the winter storms. The affected equipment will come back online after repairs are made, the agency said. And short-term lapses in operations at the site won’t affect the long-term strategy for containing or cleaning up hazards, according to the agency.

In the meantime, residents are anxious for cleanup operations to resume. “It’s certainly slowing down the cleanup process because the unit is not fully operable, you know, it can’t perform,” says Young-Medcalf. “What that ultimately means is that the plume of vapors that [the treatment system] was once extracting from is sitting there, largely undisturbed.”

Jones Road was polluted by a dry cleaning business in a strip mall. Chemicals the business used from 1988 until it shut down in 2002 wound up contaminating nearby private water wells with tetrachloroethylene, also called perchloroethylene (PCE). PCE in drinking water has been linked to a higher risk of epilepsy and cancer in people exposed in early childhood. Since then, cleanup has involved plugging up wells and pulling vapors from contaminated soil.

Disasters have put Superfund sites — and surrounding neighborhoods — in peril in the past. Hurricane Harvey’s flood waters broke a protective cap at the San Jacinto Waste Pits in 2017, releasing cancer-causing chemicals, dioxins, into the nearby river. Like many Superfund sites, the prescription for addressing pollution was to contain it on site. But after the protective cap failed during Harvey, the EPA decided to remove the chemicals.

“There’s not anything that man can make that is going to withstand the changes of this river and the forces of Mother Nature that go on there,” Medcalf-Young says. The issue now is that removing the chemicals from San Jacinto will take at least seven more years. And with storms growing stronger because of climate change, time is working against cleanup efforts. “Seven more years is seven more hurricane seasons,” Medcalf-Young says.

That’s one of the more daunting problems facing already established Superfund sites. Strategies to clean up and contain these sites were likely designed to address weather-related risks the location has faced in the past, says Jim Blackburn, an environmental law professor at Rice University. But climate change is creating new normals that remediation plans might not have taken into consideration.

“We’ve seen 100-year rain fairly often around here. These terms have lost their meaning because we have so many severe rainstorms,” Blackburn says. “We’re facing something that’s changing going into the future. And I don’t think we’re very good at understanding how to evaluate that, address it, and plan for it.”

Superfund sites are evaluated every five years if the location still has contaminants at high levels. That’s when the EPA will consider if any changes need to be made because of any additional risks posed by climate change, a spokesperson for EPA’s Region 6 office, which includes Texas, said in an email.

“The Agency’s new leadership team is aware of the issues involved in climate change and Superfund sites, and will be working with EPA staff to determine next steps to build on the Superfund program’s existing climate change approaches,” a spokesperson for EPA headquarters said in an email. It’s a reversal from the EPA’s approach under former president Donald Trump, when leadership backtracked on previous efforts to incorporate climate change into the agency’s work.

About 60 percent of all non-federal Superfund sites are in places where they’re vulnerable to flooding, storm surge, sea-level rise, and wildfires made worse by climate change, according to a 2019 report by the Government Accountability Office. That report didn’t investigate how those events or other challenges might delay cleanup, but it’s something the agency is interested in looking into in the future if Congress makes an inquiry (the GAO conducts investigations at the behest of Congress).

“You can imagine that if an area is flooded and inaccessible, that whatever cleanup might have been going on is suspended,” says Alfredo Gómez, director of natural resources and environment at the GAO. He says the agency would like to look into what kinds of challenges affect the pace and scheduling of Superfund cleanups.

“Now we know that our future from climate change is going to be potentially affected by more frequent and intense storms,” says Gómez. “How can we still ensure that these sites are going to be more protected?”