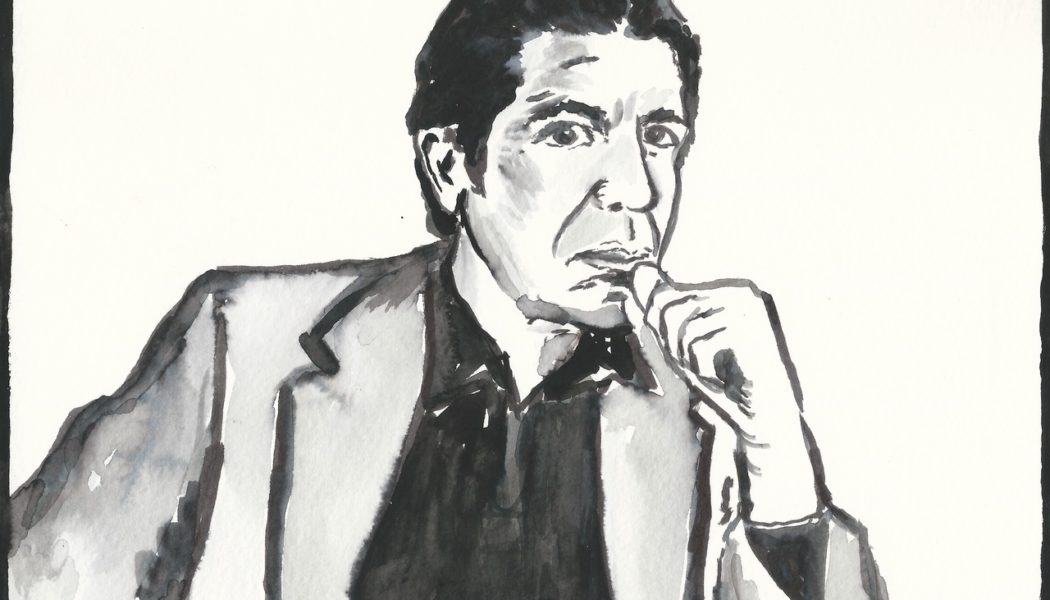

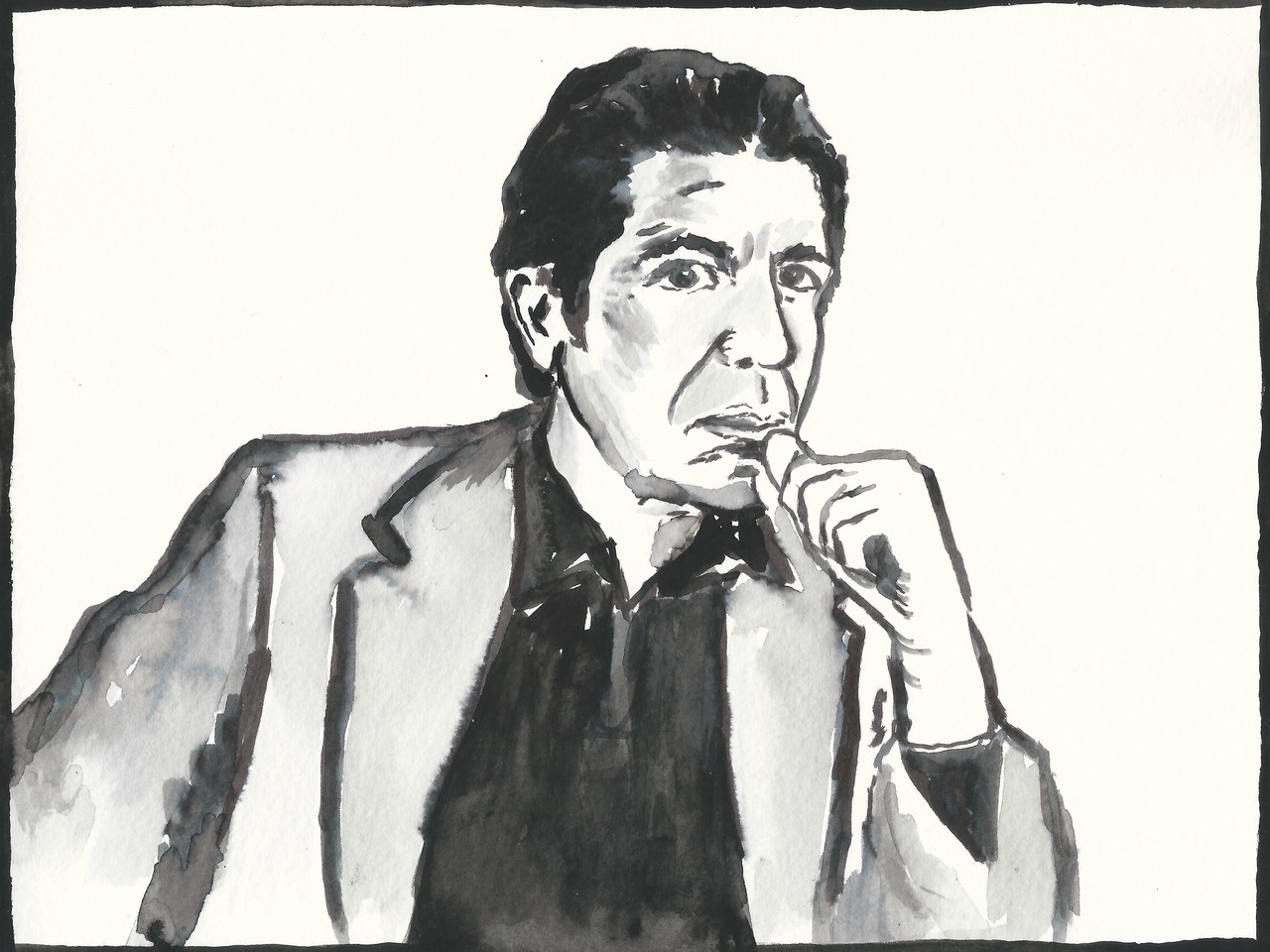

The first time I heard a Leonard Cohen song was through the surrogate voice of a dear friend, Jason P. Grisell, in Venice, CA circa 1991. Sitting on the sidewalk hunched over his beat-up acoustic guitar wearing an army green parka in the middle of a hot summer day, Jason sang an unforgettable version of Cohen’s song, “Suzanne”. The song was sandwiched between a deafening rendition of “Mercy Seat” by Nick Cave and a 13th Floor Elevators song. “Suzanne” struck me as nothing short of lyrical perfection; the words and melody remained on repeat in my messy head for hours. It haunted me like the first time I heard Gregorian chants and read James Baldwin.

Within a week of hearing Jason’s version of Suzanne, I owned four Leonard Cohen albums: Songs of Leonard Cohen (1967), Songs of Love and Hate (1971), Death of a Ladies’ Man (1977), and New Skin for the Old Ceremony (1974). I didn’t have a job or anywhere I had to be, so I immersed myself in the world of Leonard Cohen. I bought and read Cohen’s books Beautiful Losers (1966), Selected Poems 1956-1968, The Energy of Slaves (1972), and Death of a Ladies’ Man (1978). It felt as though I had found a kind of church for myself. A place to rest and belong.

I was drinking a lot of green tea at the time, always in a little ceramic cup with no handle, and I had just been introduced to the scent of sandalwood in a wooden beaded bracelet a friend brought me from Indonesia. Green tea and the scent of sandalwood always takes me back to this simple place and time; a time when all I had to do was drink green tea and worship in the Church of Leonard Cohen. What entered my heart most unguarded was the pure resonance and depth of Leonard Cohen’s voice: a feeling-felt kind of feeling, music embodied, a warm rumbling under the rib cage in my chest cavity similar to a cat’s purr. Leonard Cohen’s gentle masculinity, emotional brevity, and concise and unapologetic song craft awakened in me an unfamiliar depth and perception of the human condition.

Much like a child lost in play, I experienced a profound sense of inspiration when immersed in Leonard Cohen’s music and words, a calling to listen better and to create something out of nothing. Looking back on this time now, I suppose I was searching for what one might understand or describe as “God.” I sometimes sensed a holiness was present in Leonard’s presence and in the sonic space and mood of his poetry, grace and melody and this was comforting to me. This was a kind of spiritual beckoning. A way to make meaning of things. A landing. I felt my general sense of existential confusion, teenage angst, and aloneness was soothed by this newfound comfort in Leonard. I was soul-lost, a misfit, a seeker, and a baby-queer punk who was wholeheartedly and heartbrokenly disappointed by the world and gender I was born into, but I also had the innate capacity to rest in things like gratitude, humor and solitude, much like Leonard, who I fantasized might understand me. Resting in Leonard Cohen’s embrace I relaxed into a kind of knowing that it was all as it was supposed to be—that it all mattered and also didn’t matter—and unbeknownst to him this is when I adopted Leonard Cohen as my Godfather.

Leonard Cohen died in 2016, the same year as Prince, David Bowie, Muhammad Ali, Gene Wilder, Carrie Fischer, and Abe Vigoda. He was also a Zen Buddhist monk and devoted many years to his practice.

Tamala Poljak is in the legendary pueer punk-pop band Infinite X’s. They released a remastered reissue of their eponymous LP last February on Jealous Butcher Records, making it available on vinyl and digitally for the first time ever.