“I think this is a close call, this case,” Justice Brett Kavanaugh said Tuesday, during 75 minutes of virtual oral arguments before the high court, although he acknowledged there were “some problems” with the oil industry’s arguments.

The oil industry, backed by the Trump administration on its last full day in office, argued that federal law allows appeals courts to review all of the reasons a district judge remands cases such as this back to state courts. Four appellate courts have found that they only have a limited ability to review such orders in these climate cases — when a federal officer is involved — and each time so far have ruled against the oil companies.

Several of the conservative justices on the court signaled openness to that interpretation, but they also cautioned that such a broad review could open up “gamesmanship” in lower courts.

“You may be right, may or may not be right under statutory reading of this, but I can’t avoid the odd sense that it seems as though we are smuggling in to an appellate review of other issues that are not necessarily the issues that are front and center, like federal-officer,” Justice Clarence Thomas said Tuesday.

Liberal Justice Sonia Sotomayor echoed that Tuesday, describing the industry’s arguments as an “exception that could open the floodgates of appellate litigation in the federal system.”

The lawsuit brought by Baltimore is one of more than a dozen similar suits filed by localities and states in recent years that seek to hold the energy producers liable for the damages incurred from climate change. The Trump administration, which has rolled back dozens of environmental and climate change rules over the past four year, jumped in to help defend the oil companies.

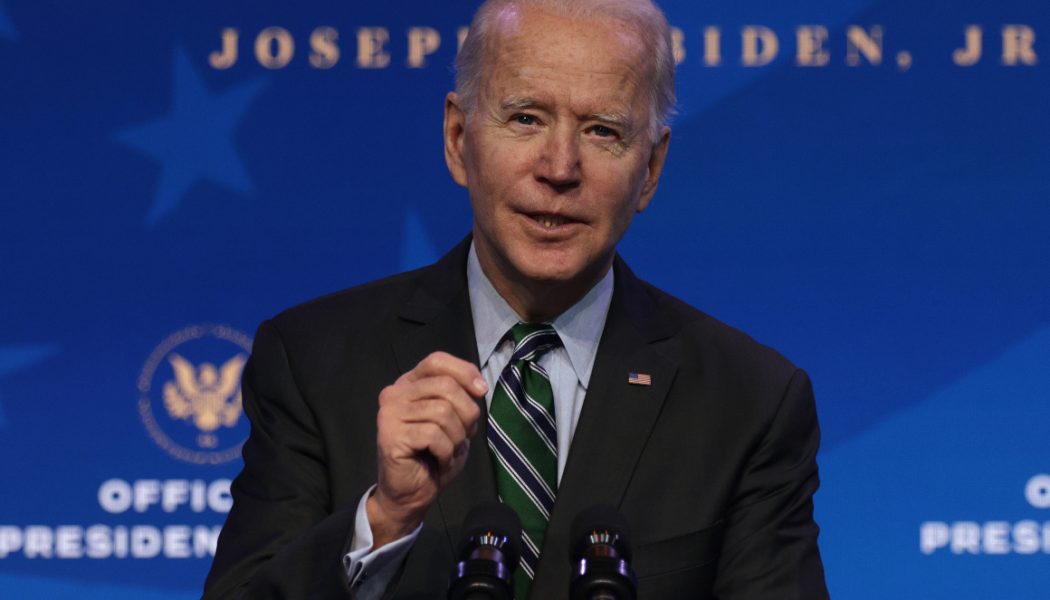

In stark contrast, President-elect Joe Biden, who has made fighting climate change one of his top priorities, has sided with the states and municipalities. He praised the lawsuit brought by his home state of Delaware against 31 companies that he said “knowingly wreaked havoc and damage” on the climate, at a September event.

The city of Baltimore in 2018 sued 26 oil and gas companies, arguing that their they are liable under Maryland state law for the city’s costs of dealing with climate change, such as the destruction caused by more extreme weather, sea level rise and increased public health risks. Similar suits have been filed in Massachusetts, Rhode Island, Connecticut, New York, New Jersey, Delaware, the District of Columbia, South Carolina, Minnesota, Colorado, Washington state, California and Hawaii.

In Baltimore and the rest of the country, the companies have tried to bump the suits up to federal court, arguing that greenhouse gas emissions and climate change are national and global matters, not issues for state courts.

The companies are pushing for the federal courts to hear the cases because it’s possible the lawsuits would be barred under federal common law. The Supreme Court ruled in 2007 that the Clean Air Act gives EPA authority to regulate greenhouse gases, and in 2011 the court ruled unanimously that states cannot seek climate damages in federal court because of EPA’s authority. That could hobble any of these climate lawsuits in federal court.

Throughout Tuesday’s oral arguments, the justices largely focused on the technical question at hand, although Kavanaugh asked the oil companies’ lawyer Kannon Shanmugam why the industry preferred the case to be in federal court rather than state court, and why Vic Sher, who represented the city of Baltimore, wanted it heard by state courts.

“This court has never held that review of an order necessarily encompasses every issue addressed in an order,” Sher said Tuesday.

Sher added that the Court of Appeals must decide if federal-officer jurisdiction exists, “not merely whether a defendant asserted it perhaps as a bootstrap to obtain review of grounds otherwise absolutely barred.”

Kavanaugh pressed that the “text in isolation” could be a problem for the city of Baltimore, though Sher argued that the plain language of the statute in question “limits and tethers the appellate courts scope of review.”

The cities and states have been winning the venue argument in the lower courts. The four appellate courts that have ruled on this matter so far — a mix of judges appointed by every president since Bill Clinton, including President Donald Trump — have all agreed that a longstanding law gives them narrow scope to review the grounds for lower court judges’ remand orders. On the one applicable ground they can review, the circuits have all agreed that the suits belong in state court.

If the Supreme Court rules for Baltimore, it would allow the other pending cases to move forward at the state level. That’s likely to improve the chances that the states and cities would prevail in winning damages from the industry.

“There’s a lot at stake,” said Sean Hecht, a law professor at the University of California, Los Angeles who previously consulted on similar climate cases in California.

In a statement after Tuesday’s arguments, Sara Gross, chief of the affirmative litigation division in the Baltimore City Department of Law, said the city was confident it would prevail.

“We feel confident in our argument that the 4th Circuit, along with many other sister circuits, got that question right in affirming the U.S. District Court of Maryland’s order sending the City’s case back to state court. The statute’s bar on appellate review applies here, and court of appeals got the clear reading exactly right.”

The high court has multiple options if it sides with the oil companies and the Trump administration. The narrowest path would be to direct the lower courts to go back and review the full breadth of reasons lower court judges gave for sending the cases back to the state level.

The oil companies, however, have asked the Supreme Court to go a step further and directly declare that climate change-related claims “necessarily and exclusively arise under federal law” and thus belong in federal court, rather than having the lower courts take another crack at it.

Whether the court will allow the oil companies to expand the scope of the case that way is “the big question” for those tracking the suit, according to Hecht.

The unanimous agreement among judges of varying stripes in the lower courts could suggests that this could be settled as a simple matter of statutory interpretation rather than a broader statement on the culpability of climate change. But Hecht said there is legitimate disagreement on the remand review issue in nonclimate cases that could influence the outcome here.

Justice Amy Coney Barrett did not recuse herself from arguments Tuesday, as environmental groups had called for because her father spent much of his career working for oil major Shell and held a role with the American Petroleum Institute. Justice Samuel Alito, who owns stock in ConocoPhillips and other companies involved in the case, however did recuse himself, leaving the court with eight justices.

Five or more justices would be needed to overturn the 4th Circuit and hand a win to the oil industry. A 4-4 tie would effectively uphold the 4th Circuit without setting a binding precedent on the other circuits. However, given agreement so far at the appellate level, that may allow for most or all of the climate suits to continue in state courts.

The case is 19-1189, BP v. Baltimore. The court is expected to rule by June.