Big projects in Indiana, Mississippi and Texas were brought online and then shut down, after billions of dollars of investment. In 2020, NRG Energy Inc. mothballed the last remaining project capturing carbon emissions from a U.S. coal-fired power plant. The Petra Nova plant in Texas, one the biggest projects of its kind in the world, stopped shipping its carbon to nearby oil fields to help boost production due to collapsing oil prices.

The highest-profile collapse was the Kemper County power station in Mississippi, which tacked on $4 billion in cost overruns before Atlanta-based utility giant Southern Co. axed it in 2017. The project was never able to capture at a large scale the emissions from lignite coal.

The 65,000 miles of new carbon dioxide pipelines that would be required to meet the White House’s national goals is far more than the current capacity for moving carbon underground. There are just 5,000 miles of those pipelines in operation today. They’re largely concentrated along the Gulf Coast and in North Dakota.

‘It’s just helter-skelter’

The Biden administration has cited papers from the Great Plains Institute and Princeton University’s Net-Zero America project that envision “an interstate CO2 highway system.” They talk about building along existing rights of way carved out for other pipelines and telecommunications lines.

Congress has signed onto that deal, too, including funding in the $1 trillion infrastructure bill it passed in November to help finance large-capacity carbon pipeline projects.

But that vision isn’t exactly being followed in Hardin County.

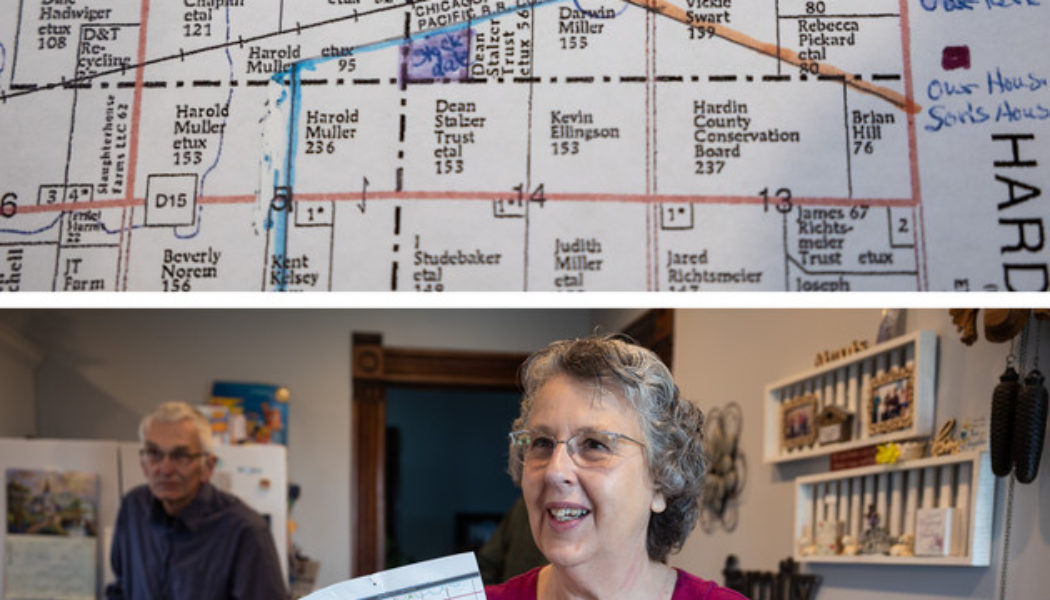

A second proposed pipeline, the Heartland Greenway by Navigator CO2 Ventures, would also run under the Stockdale property. It would cross Summit’s pipeline 12 times in Iowa alone as it makes its way to a geological sink in Illinois. Both have asked Iowa regulators for eminent domain powers to build the pipelines even when landowners don’t agree.

Maps from Summit and Navigator show the pipelines are not sticking to existing rights of way. Individual landowners complaining about plans for the pipeline to cut diagonally across their farm fields and close to their homes have filed objections with the Iowa Utilities Board. A rural water district says the Summit plan would “cause damage to every water line crossed” in their area. And a school district says Navigator’s proposed route across their property would impede construction of already-planned school buildings.

A third project has been proposed from Wolf Carbon Solutions, but the company hasn’t yet filed for state-level approvals and detailed maps have yet to be released.

“It’s just helter-skelter, pipelines in one direction, another direction — there’s no rhyme or reason to it,” said Deb Lavalle, whose Hardin County land would be crossed by the Summit pipeline. “If they really think they need to do it, keep it in the public right of way, for heaven’s sake.”

Matt Fry, a policy manager at the Great Plains Institute, a think tank dedicated to climate change mitigation that supports CCS, acknowledged that the gap between what CCS backers envision and what’s been proposed could spell trouble for the technology as these projects “will set the tone for the whole industry.”

His group is polling Iowans to understand what future projects could do differently to gain more grassroots support. Part of the problem, they believe, is that the pipeline companies are mapping out routes before going to communities and landowners first.

“People are learning as they go,” he said.

‘I am a Christian’

Concerns about safety and crop yields — and a conviction that private companies should not be allowed to use eminent domain — run so deep among landowners that many are battling the pipeline alongside conservationists at the Sierra Club.

“We’ve been told we don’t agree on anything, but we’ve found quite a bit of common ground,” said Jess Mazour, a program coordinator at the group’s Iowa chapter.

Omaha-based attorney Brian Jorde, who helped organize landowners against the Keystone XL pipeline, is working with the Sierra Club, too. He and Mazour co-host weekly Zoom strategy sessions for landowners who oppose the pipeline. They’ve also filed legal documents with the Iowa Utilities Board accusing pipeline developers of not following the letters of the law.

The board still has to rule on eminent domain issues

“At the end of the day we just have to hope that the IUB has the courage to do the right thing for Iowa and not just for the millionaires backing this project,” Jorde said. “You have to place these projects under land, and that land is owned by real people who clearly do not want them.”

The alliance is dumbfounding to those who support the project.

Seth Harder is the CEO of Lincolnway Energy, an ethanol company with a refinery in Nevada, Iowa, next door to Hardin County. He says climate mitigation is one of the main reasons the company wants to connect its plant to the Summit pipeline.

“If we have this opportunity to capture the CO2 and put it back where it came from, we maybe have a duty to do that,” he said.

He said he can understand why landowners would be opposed to the use of eminent domain on principle but can’t fathom why environmental groups aren’t more supportive. “Like the Sierra Club,” he said. “I thought your job was to help us protect the Earth, not stop us from protecting the Earth.”

Some landowners are also struggling to wrap their heads around their new partners. Sitting at the kitchen table over deviled eggs and sloppy Joes on a recent afternoon, Theresa Thoms eyed her friend Kathy Stockdale skeptically when the idea of partnering with Jorde and the Sierra Club came up.

Thoms opposes the pipeline but hasn’t signed up. She doesn’t “agree with the whole climate change thing.” But Stockdale explained to her friend how her Christian faith has driven her to work closely with the environmental group, if only just this once.

“I have struggled with it myself, but I am a Christian and I look back to biblical times when God called Joseph to Egypt to work with them and fix things,” Stockdale said.

“Sometimes God calls us to do things that we really don’t want to do,” she explained, “and God made me a steward of the land and we have to do what we have to do to take care of it.”

Pipeline politics

The race to build the pipelines comes with a big prize.

Expanded tax credits are changing the financial calculus for companies. And it feels like a small gold rush.

Any project that begins construction by 2026 can earn a $50 credit for each metric ton of carbon captured and sequestered. In the stalled Build Back Better Act, that figure would go up to $85 per ton as long as the polluter captures a high percentage of its carbon.

“Sticking carbon down into the earth does not drive independent economic benefit,” said Hunter Johnston, a lawyer at the firm Steptoe & Johnson who works on CCS policy. “So, it’s the tax credit that is driving the economics right now, and we’ve seen a huge amount of ambition.”

Summit could earn $600 million annually in federal tax credits if the company’s current carbon storage projections pan out. The $7.2 billion in tax credits the project could earn over 12 years would more than cover the pipeline’s estimated $4.5 billion up-front building expenses.

The pipeline is just the latest venture for Rastetter, the chief executive of Summit Agricultural Group and a political power broker in Iowa.

To farmers in Hardin County, Rastetter is one of their own. He grew up on a 300-acre farm near the town of Alden, in Hardin County, and got rich off the same ethanol refineries where many farmers still sell their harvest.

He made his fortune bringing large hog confinement operations to Iowa, operations that environmental groups have for decades blamed for the nitrogen pollution plaguing the state’s waterways. In the early 2000s, Rastetter got out of the pork business and invested in ethanol, founding the plant in Hardin County, now under new ownership, where the Stockdales still sell their grain.

The pipeline proposal is not the first time Rastetter has also courted controversy. A decade ago, as a member of the board of regents at Iowa State University, he involved university professors in a business enterprise in Tanzania. His firm, AgriSol Energy LLC, planned to spend $100 million to lease huge parcels of land and develop a commercial farming business in the east African country. The project was scrapped after media reports revealed it would displace more than 100,000 refugees from Burundi.

Presidential hopefuls show up in farming communities like this to pledge fealty to the future of ethanol. The high-profile agricultural summits hosted by Rastetter, a major GOP donor, have become make-or-break moments for presidential hopefuls visiting the state ahead of the first-in-the-nation party caucuses.

The political establishment, Democratic and Republican, is interwoven with the Summit CCS pipeline project.

Jess Vilsack, the son of Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack, is Summit’s general counsel. Former Republican governor Terry Branstad, who appointed two of the three sitting members of the Iowa Utilities Board, is a senior policy adviser to Summit. And the company’s vice president of government affairs was previously chief of staff to Iowa’s current governor, Republican Kim Reynolds.

The project has also received major investments from John Deere, the farm equipment maker, and Continental Resources, an Oklahoma City-based oil and gas producer founded by billionaire Harold Hamm.

‘The time is right’

[flexi-common-toolbar] [flexi-form class=”flexi_form_style” title=”Submit to Flexi” name=”my_form” ajax=”true”][flexi-form-tag type=”post_title” class=”fl-input” title=”Title” value=”” required=”true”][flexi-form-tag type=”category” title=”Select category”][flexi-form-tag type=”tag” title=”Insert tag”][flexi-form-tag type=”article” class=”fl-textarea” title=”Description” ][flexi-form-tag type=”file” title=”Select file” required=”true”][flexi-form-tag type=”submit” name=”submit” value=”Submit Now”] [/flexi-form]