Stella McCartney doesn’t want you to feel bad. The British fashion designer understands it’s easy to get overwhelmed by all the ways the products we eat, buy, and wear come with unintended consequences—for society, for animals, for the planet. And so even if she’s talking about the harrowing conditions workers suffer in fast-fashion factories or the devastating climate impact of animal agriculture, she’s eager to emphasize that the goal isn’t guilt. It’s hard work to be the best you can be, after all, especially when what many of us want is seemingly impossible: to live more sustainably without giving up the luxuries and conveniences of modern life. We want to look good, feel good, and still somehow do good.

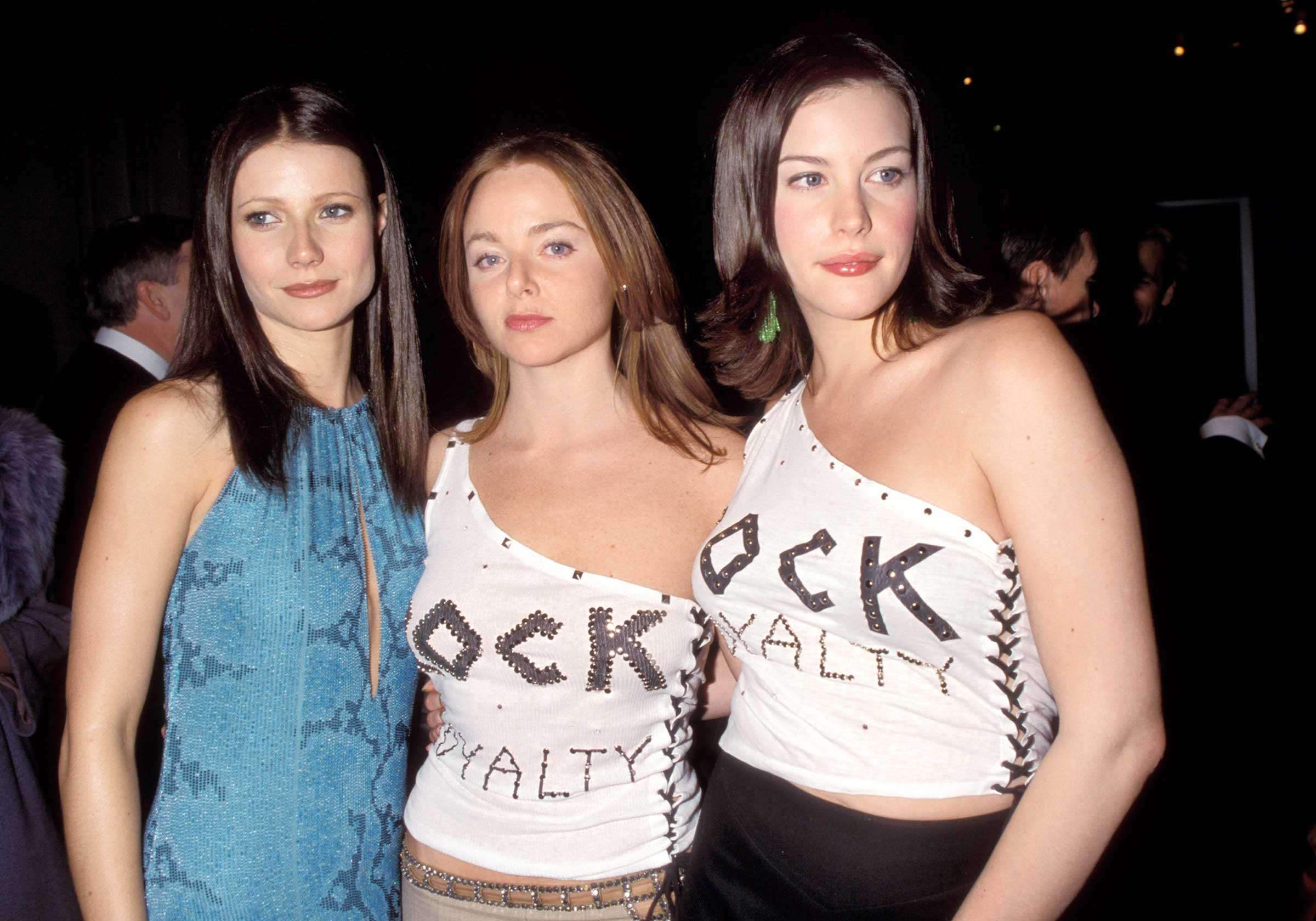

And so McCartney, 51, is trying to make that a little easier. Creator of the first ever vegan “It bag”—the slouchy faux-leather Falabella tote with a sleek silver-chain trim—McCartney has spent her career trying to show the world that ethical choices don’t have to mean compromising on glamour. Since the launch of her namesake label in 2001, she has created luxury clothing that celebrates modern femininity—her brand is a closet staple for countless celebrities—while eschewing leather, feathers, and fur. She also made a name for herself as one of the cool girls of the noughties, out with Kate Moss, Madonna, and Gwyneth Paltrow. (A 2000 Vogue profile called her “a girl who loves to make a little trouble, get a rise, stir things up.”)

Two decades on, she remains a fixture on the high-fashion circuit, making clothing that is known as much for its sharp tailoring, minimal lines, and bold aesthetics as it is for its eco credentials. She’s also a pioneer, collaborating with startups on the cruelty-free, sustainable materials—like grape-based leather, forest-friendly rayon and recycled cashmere—that made up 90% of her latest two collections. “All I’m trying to show is that you don’t need to sacrifice,” she says when we meet in her London office in July. “You’re not being penalized for your choices.”

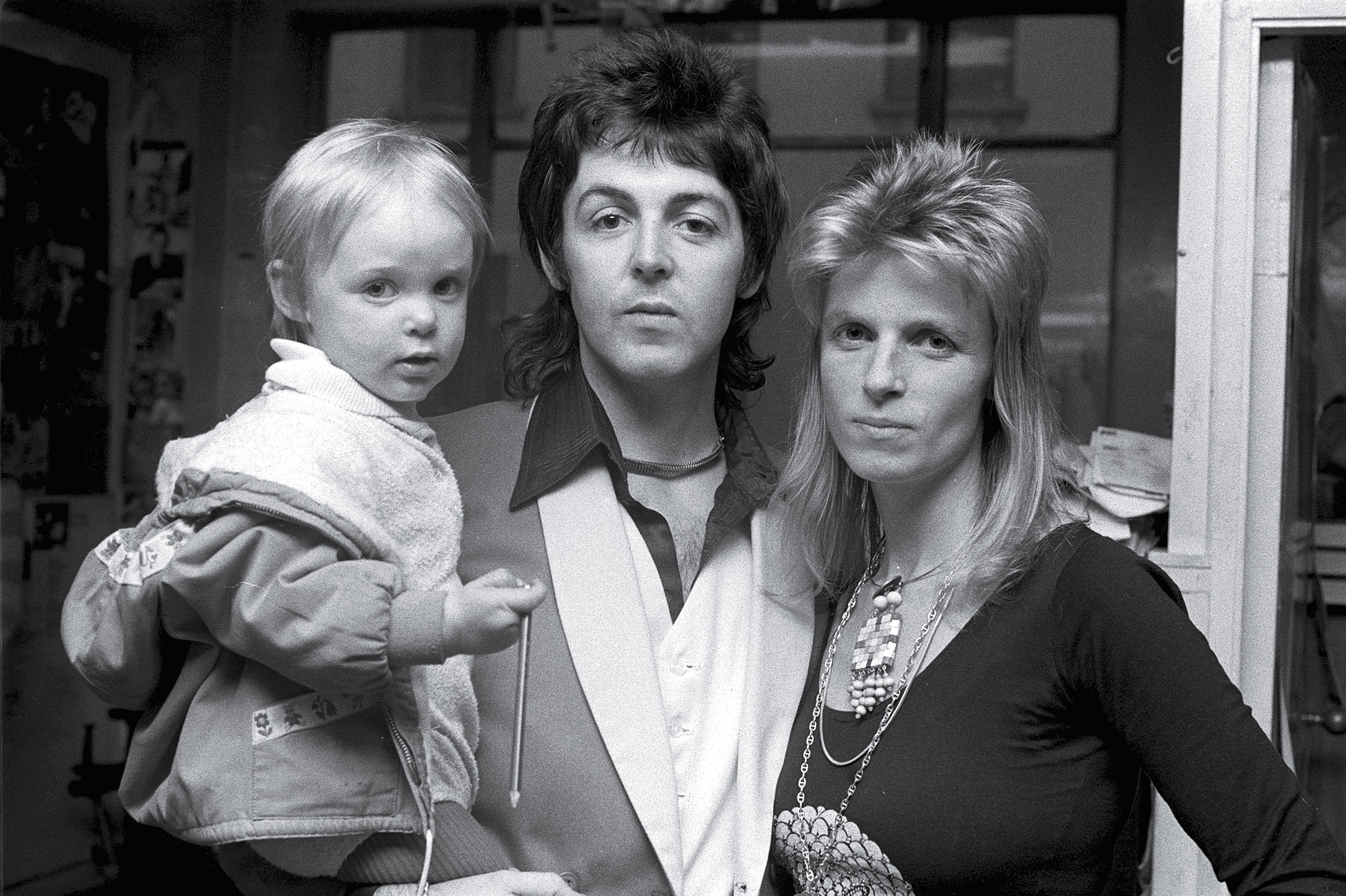

McCartney had a running start: she’s the daughter of two prominent animal-rights activists who wrote protest letters to companies involved in animal abuse, lobbied against fur, and published vegetarian cookbooks. They also happen to be music royalty: Beatles legend Paul McCartney and the American photographer Linda (who died in 1998), who built a home in the countryside but also took their kids on the road with their band, Wings. “One side was this farm life, and the other side was the stage, with glittery boots and glamour,” McCartney recalls. “It was an early inspiration.”

She has since established herself as a British fashion icon in her own right, designing the uniforms for Team GB Olympic athletes and Meghan Markle’s wedding-reception dress. “It was impossible for fashion to think of luxury and sustainability in the same breath before Stella changed that,” Anna Wintour, chief content officer of Condé Nast and global editorial director at Vogue, writes over email.

McCartney’s work increasingly extends beyond her own label: in the past few years, she has met world leaders at the G-7 and the U.N. Climate Change Conference and co-founded the $200 million Collab SOS fund for climate solutions. As sustainability became a business imperative, her brand became more desirable. In 2018, she bought back the 50% stake that Kering had held for 17 years—only to team up the following year with Kering’s chief rival, LVMH (Moët Hennessy Louis Vuitton). There, she was appointed special adviser on sustainability to CEO Bernard Arnault, one of the world’s richest men, who said in a statement that “a decisive factor was that she was the first to put sustainability and ethical issues on the front stage, very early on.”

The minority stake provides both the freedom and the cash to continue innovations that might not turn a profit. Her namesake brand reported a loss of more than $40 million in 2021, the third consecutive year of a loss of more than $38 million, following the split from Kering and the business challenges of the pandemic. Now, as McCartney brings more eco-friendly materials into her own collections, she also collaborates with LVMH—Europe’s largest company by market value—to encourage its other maisons (among them Loewe, Dior, and Givenchy) to do the same.

Read More: Why the Staff of Europe’s Most Valuable Company Is Getting ‘Climate Training’

In an era when many make claims to sustainability, few have been doing it as well, as stylishly—or as long—as McCartney. “When I first started, I was definitely the eco weirdo in the room,” she says. “But why would I compromise what I believe in morally to go into an industry I’m passionate about?”

Raised vegetarian, McCartney traces her connection with nature to her childhood, which she spent riding horses on a remote Scottish farm and hiking trails in Arizona. Her parents may have been icons, but Linda, who had rejected her Park Avenue life to tour with rock stars, and Paul, the working-class Liverpudlian who became a household name in his 20s, wanted to keep their family grounded. They chose to send their four children to local schools, opting against the private education favored by wealthy Brits. “They had to take a bit of flak for having a famous dad, but it toughened them up,” Sir Paul McCartney recalls, sitting in his office overlooking London’s Soho Square. A Wurlitzer jukebox glows in one corner, and he points out a pair of spectacles that once belonged to René Magritte, a present from Linda. “Now I’m just showing off,” the 81-year-old says, laughing.

He and Linda always had “slightly offbeat tastes in fashion,” he adds, and from a young age, Stella would spend hours pulling together outfits from their shared closet. In 1997, just two years after graduating from Central St. Martins, the renowned art and design school in London, 25-year-old McCartney was appointed to succeed Karl Lagerfeld as creative director of Chloé in Paris. “More Clueless Than Couture,” a Vogue headline read at the time. “I think they should have taken a big name,” Lagerfeld sniped of his successor. “They did—but in music, not fashion.”

“She had to prove herself,” her father says. “I said, if she doesn’t do well at the end of that year, then the name is not something to help, it’s a cudgel to beat her with. But she did well.”

At Chloé, where McCartney worked with her former classmate Phoebe Philo, the pair injected a raunchy sensibility into a French house known for soft femininity, designing low-slung skintight pants, see-through gold-chain tank tops, and skimpy sequin dresses. McCartney also stuck to her values; no collection she’s ever designed has used animal products. She acknowledges that her ability to uphold her convictions comes partly from being the daughter of one of the most successful men on the planet. “As one of the first nepo babies,” she says wryly, “I had the privilege of choice. I’m very aware of how lucky I’ve been to be accepted to work in this way since day one.” Aja Barber, a stylist and author of Consumed: The Need for Collective Change: Colonialism, Climate Change, and Consumerism, commends how McCartney has used her platform to drive change. “The fashion industry runs on privilege and nepotism,” she says. “So why isn’t everyone making the same choices that Stella McCartney is making?”

Those choices are not always an easy sell to CEOs. “I’ve had moments where I’ve been challenged very heavily to change my morals for the success of the company,” McCartney says, recounting instances when she was urged to incorporate leather into her line for better margins. (She has appealed to leaders to review policies that may favor leather goods over synthetic ones.)

But if fashion is meant to be about dreams and fantasy and escaping from reality, as McCartney says, that makes it hard to force a broader reckoning with its harms. The industry was responsible for more than 2 billion metric tons of greenhouse-gas emissions in 2018—equivalent to the output of the U.K., France, and Germany combined—according to McKinsey. Around 60% of all clothing winds up in landfills or incinerators within a year of production—the equivalent of a truckload of used clothing being dumped or burned every second. While cheap, accessible fast fashion drives much of the environmental degradation, luxury brands aren’t exempt: in 2017, Burberry notoriously destroyed $37 million worth of merchandise to maintain its reputation of exclusivity. (It has since stopped the practice.) Every year, the global leather industry—on which luxury fashion houses depend—is involved in slaughtering more than a billion animals, while tannery workers are exposed to toxic chemicals. “That is the glamorous industry of fashion,” McCartney says.

While concerns over animal cruelty were always front of mind, McCartney’s focus expanded after the publication of a 2006 U.N. report that stated that livestock production is responsible for more emissions than the entire global transport sector. In response, she launched the Meat-Free Monday campaign in the U.K. with her father and her sister Mary, encouraging the public to adopt a weekly meat-free day, and examining how to make her own lines more sustainable. Paul says Stella’s strategy of offering people better, ethical alternatives—rather than guilt-tripping them—was inspired by her mother, who launched a successful vegetarian-food business. “Linda was a pioneer and she was very strong, very ballsy, like Stella is,” he says. “It’s difficult. But she’s showing it’s not that difficult.”

In the bright white lobby of the Stella McCartney offices in West London, scenes from her widely praised show at Paris Fashion Week in March play on loop. Dappled gray horses canter alongside models wearing her Winter 2023 collection: furry overcoats, checked blazers, sharply tailored jackets, silky asymmetric dresses. The models sport thigh-high boots and carry handbags that, though you could never tell, are made from grapes, apples, or other plant-based materials.

Vegan fashion may not harm animals, but it can still harm the planet. Most vegan leathers are made from polyurethane (PU) or polyvinyl chloride (PVC), which can release microplastics into the environment. McCartney’s team hopes to minimize such effects by working closely with startups to find greener alternatives that can match the quality and durability of leather. It’s an incredibly complex, costly, and lengthy process: McCartney’s team starts by testing swatches of each new material, examining its feel, scent, resistance to scratching or tearing; they then make a prototype handbag to test its color retention and strength. Feedback is relayed to the scientists to refine the material over months and years. A major part of the work, McCartney says, is communicating their needs to scientists unfamiliar with the fashion industry. “I know the product needs to be tested in this way, to drape, to breathe,” she says, “to say ‘That color doesn’t work’ or ‘That fabric cracks.’” When the Stella McCartney team first met with NFW, the company that makes Mirum—a plant-based, plastic-free, and circular leather alternative—in March 2022, the material was too thick for anything other than firm, structured bags. But through working with them, a thinner, more flexible option is now available.

These collaborations often involve startups in early stages of development, and scaling for wider uptake will likely take years. And even after all that, achieving 100% sustainability is challenging; with the exception of Mirum, bio-based leathers require a PU coating to prevent scratching.

Working with small startups can also be unpredictable. In 2022, Stella McCartney produced the world’s first-ever Mylo luxury handbag made from mycelium, the rootlike system of fungi, but Mylo recently halted production because it wasn’t able to fundraise enough. Other materials can be impractical: her collaboration with startup Radiant Matter on biodegradable sequins led to Cara Delevingne wearing a Stella McCartney–designed BioSequin jumpsuit on Vogue’s April 2023 cover—but each fragile sequin had to be hand-stitched. And other non-PVC sequins lack the color range of traditional ones. “I get driven and angry,” McCartney says of the limitations she faces compared with her peers. “But these are the kinds of things that make me want to get up in the morning.”

The results, she feels, are worth it. Her Winter 2023 collection includes a version of the brand’s iconic Falabella made from Mirum, as well as over-the-knee boots made of Vegea, derived from wine-grape waste, and faux-crocodile handbags made from AppleSkin, a by-product of juice and jam production. There’s a particular thrill McCartney feels when customers have no idea that they’re buying shoes made from grapes, or a blouse made of regenerative cotton. “We can win if there’s no sacrifice on a dream,” she says, “on desirability, on luxury, on escapism.”

Despite her success, McCartney still has her detractors. She tells me several times that she is not perfect and that her brand isn’t either. Though she has a focus on reusing stock and waste material, she’s still in the business of making new products—though it’s unlikely an $1,100 Mirum handbag would be thrown out quickly. “My solutions aren’t there price-point wise,” McCartney says, noting that she encourages her four children to buy second-hand clothing at charity shops over fast fashion. She also has a sportswear collaboration with Adidas. “I’m a firm believer in less is more. Buying luxury—something made well, that is a timeless design—is an investment, and now there are businesses that support resale and rental.” (Stella McCartney was the first official brand partner of luxury consignment site The RealReal.)

There’s also the question of how feasible it is for McCartney to really make change within LVMH. CEO Arnault may have praised McCartney’s values, but just a few months after their deal, he publicly criticized climate activist Greta Thunberg for “surrendering completely to catastrophism.” Ever since her early days at Kering, McCartney has been accused of getting into bed with the fur-wearing, leather-toting enemy—something she describes as “infiltrating from within.” She has a history of success: in 2010, she banned the use of the notoriously toxic PVC at her label, a move later adopted by all Kering brands, from Saint Laurent to Balenciaga. Industry norms may be stubborn, but McCartney says the work at LVMH has been exciting and rewarding. “If I can have a seat at that table—where the decisions are still made—I want to be there. I’m pleased to say it’s not just bullsh-t.”

The partnership with LVMH, she says, is already yielding results. McCartney’s Summer 2023 collection includes a T-shirt made from 100% regenerative cotton, a first in luxury, emblazoned with a blue “Snog a Log” graphic—a classic example of what Wintour calls McCartney’s “wonderfully tongue-in-cheek sense of humor.” Since 2019, the brand has been working with Soktas, a family-owned cotton producer in Turkey, to help it transition away from conventional cotton farming, which uses harmful chemicals to control pests and boost production. The regenerative-cotton project started with 5 hectares and grew to 55 in 2022, her team says; LVMH has now taken over the Soktas funding, which will further expand the project.

Read More: What Happened When I Realized My Cheap Clothes Were a Global Problem

That helps keep McCartney going. But behind it all is a drive to connect with consumers through her clothes. She considers fashion a service industry. When she’s working on a collection, she’s thinking about how a Stella McCartney-designed piece should make you feel: confident, comfortable, alive, effortless, sensual. “I want to feel the best version of myself,” she says, her eyes lit up. “I want to feel f-cking fabulous.”

—With reporting by Leslie Dickstein/New York and Armani Syed/London

- Extreme Heat Is Endangering America’s Workers—and Its Economy

- The Creative Ways Teachers Are Using ChatGPT in the Classroom

- Stella McCartney Is Changing Fashion From Within

- What Trump’s Cases Mean for Biden

- The Science Behind Why We Eat So Much at the Movies

- How the U.S. and Iran Can Turn the Dial Down: Column

- Podcast: Why Candace Bushnell Regrets Thinking So Much About Relationships

- Sign Up for Extra Time, Your Guide to the Women’s World Cup