There was a time period, let’s call it 15th century Europe, where a select group of men made their bones in a variety of different occupations. Leonardo da Vinci, just to pull one name out of my hat, was not only a famous painter, but also a sculptor, scientist, philosopher, and mathematician. Apparently there’s some evidence that he was also a pretty good dancer. There were others, too. There are always others. Fast forward 400 years: Not content with just proving relativity, Albert Einstein was also a classically trained violinist. Sort of like how Axl Rose is some hayseed with chops like Chopin. We labeled these individuals Renaissance Men. Or, to use the parlance of our times, Idea Birthing Persons.

I first met the writer, musician, and surprisingly nimble dancer himself, James Greer, in 2010 when he showed up one Saturday afternoon at the front door of my Echo Park apartment, holding a bottle of red wine and a copy of his then-new novel The Failure, a picaresque story about two guys who plan to rob a Korean check cashing store in order to finance the prototype for a ridiculous internet application. The book is a gem.

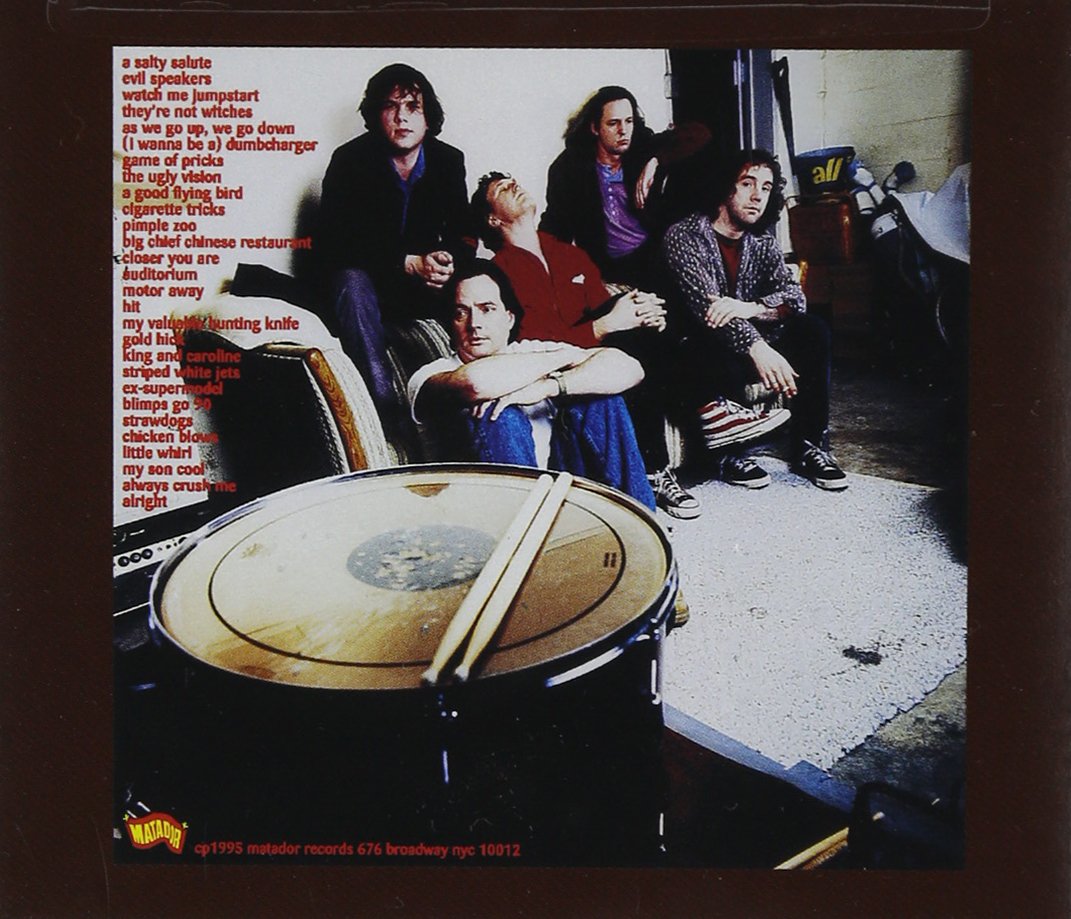

My interest in having Greer read at my house is due to his involvement many decades ago with my favorite band of all-time, Guided by Voices. Greer played bass, briefly, for the band during their lo-fi ‘90s apex. The rare photo of him exists on the back cover of the vinyl copy of the 1995 album Alien Lanes, a record Village Voice critic Robert Christgau clearly didn’t understand. Fellow Daytonian, Dave Doughman, of Swearing at Motorists, was the one who clued me in that Greer was residing in Los Angeles. I found him on Facebook and sent a friend request. I then discovered that The Failure was about to hit shelves. A reading was set, a friendship made. Neither of us have a Facebook account now.

Greer was early to the book reading I was hosting in his honor. Back then I hosted a handful of living room shows, mostly comedy, which featured my now-defunct sketch comedy group, The Dickheads, as well as a concert by the indie rock band Swearing at Motorists. Greer uncorked the wine and poured us each a glass. We made small talk, mostly about traffic, and how bad it is, as that is all Angelenos can really talk about. As guests began to arrive, Greer took a seat in the corner of the living room, next to the window.

He opened the night with a Q&A. Nobody asked a question. So, after wrapping up that short segment, he started to read. And then stopped and proceeded to engage in a bit of celebrity gossip. Eager to keep butts in seats, I opened more wine.

Close to 3:00 a.m. Greer and his partner, the musician Lola G, made their way towards the exit, where I had first met them almost half a day earlier. Greer thanked me for hosting the reading and signed a copy of The Failure, which I’ve since lost. Or, more accurately, I lent the book to this guy which he lost. We made plans to grab a coffee and continue our spirited discussion about the perils of the 405 freeway.

After closing the door on the final guest of the evening, it dawned on me that Greer, who had been present in my house for hours, with the explicit intent to help push a few copies of his novel, probably read from the text a total of seven minutes!

[embedded content][embedded content]

James Greer was born somewhere on the East Coast in 19-something-and-1. The youngest of three boys, Greer, from an early age, showed promise in both music and writing. He was also decent tennis player. At least that’s what he once told me. Like many young men who wish to pursue a career in music or writing or both–but not tennis–he moved to NYC in the early ‘90s, where he soon found himself writing about music for a spunky music magazine called SPIN.

Greer’s tenure at SPIN was brief, but influential. He helped shape the magazine into a much-appreciated tonic to mainstream rock coverage like Rolling Stone, which at that point was far removed (and still is) from their Gonzo heyday.

In a barely remembered haze known as the “mid ‘90s,” Greer found himself darting across the world, covering various subjects for SPIN, moving to Dayton, Ohio, where he dated the Queen of indie rock Kim Deal, and playing bass in Dayton’s own Guided by Voices. There was also quite a bit of drinking going on. Like, a lot of drinking. That’s not an indictment of anything other than people who reside in Ohio like to drink. Like, a lot. I’m from Ohio. I know from experience.

It was during this period that I first became aware of the writer James Greer. As a pubescent, I held a subscription to SPIN. SPIN and Sports Illustrated, those were my reading materials, as my only interests at that age, before the notion of sex became viable, were rock music and baseball.

Anyway, sobering up (sorta) and saying goodbye to all that, Greer left Ohio for Hollywood, where he soon began his now two-decade long career as a screenwriter, having written (or co-written, with Jonathan Bernstein, another former SPIN writer) pictures for Jackie Chan, Larry the Cable Guy, and Steven Soderbergh.

In between those film projects, Greer established himself as a literary wizard, first with 2006’s award-winning Artificial Light, then followed up by the aforementioned The Failure. In 2013, Curbside Splendor published a collection of Greer’s short experimental fiction entitled Everything Flows. To promote the book, I portrayed Greer at numerous readings around Los Angeles. It sold hundreds.

Now, nine years later, Greer is back with the dizzyingly funny Bad Eminence. The sort of novel Vladimir Nabokov might’ve written after having drunk a few too many Moscow Mules, which he might’ve learned how to make while reading the novel, which features recipes utilizing director Steven Soderbergh’s own liquor brand Singani 63.

Bad Eminence is the sort of literary novel that takes on the very concept of the “literary novel,” while also taking the piss out of French people and praising Juno Temple’s apparently perfect hair. It is a profound work, but, you know, with jokes.

Vanessa Solomon, the book’s main character, is a privileged and misanthropic French-American translator, who, in her spare time (which is every single moment) hates her famous movie star twin sister. Working on an English translation of thriller by a dead author, Vanessa is offered another, much more lucrative gig: translating the newest work by a crabby, chain-smoking French author who in no way meant to resemble real-life, crabby, chain-smoking French author Michel Houellebecq.

Soon, Vanessa begins to notice the previous project fighting for attention by becoming the plot of her own life. Stories collide as Vanessa is dragged down rabbit holes within rabbit holes before the meaning of life is translated before her eyes. Again, with jokes.

As if writing novels, screenplays and playing bass on the greatest song ever recorded isn’t enough, Greer is also the co-creator of the hit digital series The Horse’s Mouth, a food and comedy show that co-starred Juno Temple, Matt Jones and yours truly. Greer is currently putting the finishing touches on his directorial debut, an indie feature entitled Mirror Moves.

Asseveration #1: Novelist Matthew Specktor (American Dream Machine, Always Crashing in the Same Car)

I think of James as working within a certain postmodern tradition — of John Barth, of Stanley Elkin, of Nabokov, of Sterne — that’s certainly in eclipse in terms of its popular appeal. But that’s what writers do, consciously or otherwise: we work within traditions, we extend them, we try to keep them alive (or conversely, to kill them). Jim’s work has such enormous vitality, though. Like any good writing, it has an immediacy that also makes questions of “tradition” feel a little moot.

But, y’know, writers like to experiment (because why would you write a book that looks like all the other ones you or other people have written before), and readers often like to be comforted (because life is unpleasant enough, and books are expensive, so why wouldn’t you order the thing off the menu you already know you like?). Sometimes you can get lucky — and I’m speaking here of “readers” as an undifferentiated mass, not as idiosyncratic individuals — and trick them. Others, well, you keep writing your forward-thinking shit and hope someone notices later. We all know how many times David Markson was rejected with Wittgenstein’s Mistress. So I figure I’m getting in on the ground floor by building my statue of Greer in the living room now instead of 30 years from now when I’m too senile to remember how to do it anyway.

More seriously (right now that statue is just a pat of butter on the floor my dog hasn’t noticed yet, but it’s a start) you push on because your talent compels you to push on, and because (I suspect this is true of James especially) you simply don’t care. A book like Bad Eminence remains its own reward on some level, too. One can’t write a book that’s as straight-up pleasurable to read as that without experiencing the delight in its writing. At least, I sure hope so.

I caught up with Greer over a video chat from his home that is about a stone’s throw away from Meryl Streep’s. Sure, Meryl owns more than one home, but one of her homes is near Greer’s. We spoke about the perils of creating, his time at SPIN and the nature of reality. And other things.

SPIN: Do people still read novels?

James Greer: Depends on the genre. I think there are some that still sell. I think I was told at some point that the audience for literary fiction is about 2,000 people. Unless you break out of The New York Review of Books crowd, at least. Two thousand people — abysmal.

I think more than 2,000 people live in my apartment complex, which only consists of 10 units, by the way.

So, yeah, I don’t know if anyone reads anymore. I read!

As do I!

You and me. So if we were representative of the audience then there would be a healthy publishing industry.

But we’re not. So, nobody reads anymore. And they’ve stopped going to the movies. My big question, then, is: Why bother making anything? Why put forth all this effort into something that the public will by and large not care about?

What’s the other option? Not doing anything?

Perhaps that’s the next artistic movement — not making something. Having the idea and letting it go off into the ether. Just don’t do it — now there’s a trademark!

Whenever you make something and put it out into the world, there’s always so much shame and self-loathing attached you have to wonder why you even bothered. But theoretically, I think, by putting it out there and people liking it you might get to do it again.

Great, more anguish. But you did write a novel so I feel like we should talk about it. Because it is terrific and I’m glad that it exists. What was the genesis of Bad Eminence?

I was in Paris and a friend of mine who lives there was telling me how she went to school with the actress Eva Green and that Eva has a twin sister who everybody thought, at the time, would turn out to be an actress, because she was very extroverted, whereas Eva was reserved and bookish. That was the initial seed, “What if you had a twin that had the life you thought you deserved?”

I was also reading the Alain Robbe-Grillet novel Recollections of the Golden Triangle, which has a very non-narrative narrative. Which is cool. So what if this bitter twin was also working on a translation of Recollections — which is about an underground S&M scandal involving rich people.

Saving and moans.

(Groans) Sure. Then I was like, what if she starts translating the book and the plot of that book starts happening to her, which is a very Robbe-Grillet thing to have happen. That was basically it. I threw in some other things, too.

Who doesn’t love other things?

As I worked on it, it developed into some other things, other interests, like Francesca Woodman, a photographer who committed suicide in 1981. And the whole idea of reality as a translation, in general. All my ideas, whether they are books or movies, start out as “what if?” For example, in Unsane, [Jonathan Berenstein] and I were reading how a person could be involuntarily committed because they answered yes to the question, “Have you ever thought of killing yourself?” So, what if this happened to a woman and she’s trapped inside with her own stalker? And then it was, is this really happening to her or is it all in her head? That seemed like a fun idea, so we wrote it.

It was fun.

Writing a movie is very different from writing a novel. There are strict guidelines that you have to adhere to in the development of your script. You can get tired of that. You can feel constricted by that after a while. When I write a novel, I enjoy ignoring all that stuff and doing whatever the hell I want. And, also, play with language a lot. I’m interested in language, I speak a few [French, Latin, Money]. I like the way words mean different things in different languages. Basically, writing novels allows me to use muscles I wouldn’t otherwise use writing movies.

You still deliver a pot-boiler. One that might be happening all in her head.

I like to explore the dividing line between reality and illusion. What is reality? I still don’t know. I doubt I’ll ever know. Is this interview even happening?

Barely. In the book, are you also poking fun at Michel Houellebecq?

Not really. (beat) Yes. It’s not so much him as the popular idea of Houellebecq, the misanthropic, stereotypical Frenchman. Which in real life, he most certainly is not. Or maybe he is, I’ve never met him. And once I had the double conceit (V and her twin), I doubled that, because I thought it was a funny idea that Houellebecq was really just an actor playing a French author. The double is a concept in literature.

Yeah, the double.

Even before Dostoevsky. So, yeah, what if this author was just an actor for the actual author. I have, on occasion, resorted to employing certain people, whose names cannot be mentioned, for legal reasons, as myself in personal appearances as an author. I thought, that would be cool, that the real Houellebecq didn’t have the right image, as a chain-smoking, misanthropic French writer, so he would hire a guy who has the right image and he is going to be for all public appearances and split the money with him.

I don’t remember getting paid.

This guy has money. He can pay people things. And that’s a full-time job, representing a public celebrity. Whereas I am not a celebrity, nobody even knows what I look like. Therefore, I can send you out and only one old lady knew something was up.

She was pissed.

Asseveration #2: Bob Guccione Jr. (Founder of SPIN)

My first impression of James was that he was shy. This was incorrect. Although he is, one to one, shy, he spoke to whoever he needed to for his pieces and went everywhere he had to and charmed everyone. And he was literally a rock star! In Guided By Voices, performing in front of thousands of people.

My other early impression was that he was either a genius or a serial killer. I was right about that — he’s a genius, a unique writer who effortlessly captures the humanity and humor and absurdity of a moment. Very few writers genuinely do that.

James is just a great writer, in the gifted, true literary way (not the faux, precious sense of the current literary scene, where writers have all the pretense except the bit where they write transcendently). So he differed from his peers in that he was more adroit in his craft than most anyone else. He differs from most writers today — not just music writers — because he really knows and respects language and has the balls to say something, instead of cowering under his desk, scared how social media might react.

James had tremendous influence at SPIN, because he wrote such delicious articles he could part the Red Sea at the magazine, so to speak. He quickly got to the point where he could do whatever he wanted. I totally trusted him, and he trusted me, and I never changed a word he wrote, no matter how much pressure a musician or publicist or record executive tried to assert. Those were purer, more honest and braver days.

Can we talk about the SPIN days?

Sure!

How did you first get involved?

As you do, you meet Bob Guccione Jr. at a party, introduced by mutual friends, who also tells Bob that you’re a writer and musician, and we hit it off. There was a position open, because there was fairly heavy turnover at SPIN back then, because we weren’t making money at first, we were a scrappy upstart. There were always rumors, “Are we even gonna be in business next month?” You know, because we covered music that was by definition not popular.

Writer’s note: During Greer’s tenure as Senior Editor, SPIN went from a pebble in Rolling Stone’s shoe, to being at the forefront of the Grunge Era, due, in large part, to their coverage of a small three-piece band from Seattle named Nirvana.

I think when the album Goo by Sonic Youth came out, I interviewed them and wanted to put them on the cover. Bob wanted to put Billy Idol on the cover. This is 1990, I believe.

Sure, I get it. Ford Fairlane had just come out. Billy Idol was hot again.

He wasn’t hot! There was a fairly heated editorial meeting. Bob was telling me that I couldn’t be objective about who was on the cover since I wrote the story. But it wasn’t about me getting a cover story. The argument wasn’t about who would sell more copies. Long story short, we ended up putting Billy Idol on the cover and it sold a lot of issues.

My argument was Sonic Youth is who our audience is. It’s the audience we should be trying to cultivate. I was dead wrong at the time, but I was accidentally right, because a year later, Nirvana happened. We got that one right. Bob agreed to put them on the cover before their album even came out. Because enough of us around the office knew they were gonna be big. We didn’t know they were gonna be that big. Nobody did. Nobody knew anything. It was unusual we, or anybody, could be that out ahead of something. So we put them on the cover of our New Music issue. Overnight, our subscriptions doubled.

What’s fascinating is that in 1991, when Nevermind came out, there were a number of iconic albums from established bands that had also come out. You had Guns N’ Roses…

Who?

Um, I guess you would describe them as a glam metal band.

The only thing I remember about that Guns N’ Roses record was that they called Bob out.

That’s what I’m getting to. I remember looking up who Bob was because of that and started subscribing to SPIN. And inadvertently, it created a rift, because Rolling Stone was the magazine that would cover Guns N’ Roses, whereas SPIN seemed focused on underground music.

After Nirvana, it got easier, because you could put, I don’t know, Juliana Hatfield on the cover and still sell a healthy amount of copies, because she had a video on MTV.

Here’s my take on the whole Nirvana thing: At the time, we thought this great new beginning for rock music, that the stuff we loved that started with punk rock, and then morphed into hardcore, college rock, the stuff that was bubbling up in the ‘80s, finally breaks out into the mainstream with Nirvana, and it seemed like the start of something really interesting and potentially revolutionary. What it actually was was the end of rock music. I’m talking about rock music as a viable popular form, it was the last gasp. In retrospect, Nirvana was the last rock band. There have been other rock bands, obviously, but they’ve either been terrible or didn’t sell records.

And you got to know Kurt a little.

Yeah. We were friends. I was probably one of, if not the last person to see him alive. It’s also the reason why I quit SPIN. I happened to be in Seattle when he killed himself, on assignment for SPIN doing my widely ignored series “A Year in the Life of Rock & Roll.”

One of my favorites. I think it’s available online. We could direct people…

No, no, no, no, no, no.

Anyway, I happened to be hanging out at Sub Pop. When Kurt killed himself, they called me first, and I knew I couldn’t cover it. But instead of telling them that, I just went, “Okay” and ignored their desperate phone calls over the next few days and then flew off with The Breeders for their tour. I could’ve handled that better, from a professional standpoint, but it felt ghoulish to me. All these journalists flooded Seattle, and they each were like, “I hate this part of the job, but if anyone’s gonna cover it, might as well be me.” Nobody was gleefully licking their chops, metaphorically or otherwise, but I’m just looking at these people and thinking, “You don’t have to do this.” It felt like the vultures were flocking to the corpse.

The other thing, had I done my job, I wouldn’t have been able to spend the days at his house, hanging with his family and going to the funeral. I couldn’t have done it in my capacity as a journalist. So SPIN had to scrap a whole issue and just fill it with tributes instead. For me, on a personal level, I feel bad for letting down my colleagues at SPIN, but it wasn’t a choice for me. I’m just very passive aggressive.

Then you left for Ohio, land of disenchantment. I always say you have the ultimate rock critic story: You land one of the babes of indie rock [Greer was briefly engaged to Kim Deal of Pixies/The Breeders] and then you somehow find yourself in one of the coolest bands in the scene with Guided by Voices. How did you end up in GBV? Besides drinking playing a part in it.

Drinking always plays a part. They needed a bass player. Bob [Pollard] and I were already friends and we hung out in the same bars. He asked me to be in the band, it was sorta presented to me as this part-time gig. They didn’t really tour back then. They spend a week making a record.

A week?

That’s for an ambitious, double album. But as soon as I joined, it quickly turned into a full-time gig, because we signed to Matador. And, as you can imagine, it caused a strain on my relationship. Kim went on tour, Guided by Voices went on tour. So, I understand what you’re saying about the rock critic narrative, but, for me, it was not a happy time. It was a tumultuous time. My relationship with Bob was always tempestuous. Still is. Bob is a tempestuous person. And I was always traveling, whether it was for Kim or GBV or SPIN. I never felt like I had any time to myself. And I was always drunk. Or often drunk. There’s always a temptation to look back on things and be nostalgic about them, but I don’t see a lot of things…a lot of people died (laughs). There was a lot of hard living going on back then.

Let’s cut ahead 30 or 40 years and you’ve made a movie.

Yup. I just finished my directorial debut. It’s a companion piece, in a way, to the novel, only in the sense that it’s a non-linear, non-narrative experimental work. Mirror Moves is based on the actual story of the Green River Killer from the ‘80s and, apparently, and this is the only part of that story that interested me, was that he was married to a woman for 15 years who had no idea. So my “What if” was what if we told the story about the day she learned her husband was a serial killer and did her mind fracturing, from her perspective?

It’s my first time making a feature and it was a lot of work. After the first or second day of shooting, I texted Soderbergh and asked, “Why didn’t you tell me this directing thing was so hard?” And he wrote back, “It’s only hard if you want it to be good.”

For me, I realized, I should probably have been [directing] all along. I was trained as a musician, on the tenor saxophone, so I’ve always been a musician. I’ve been a writer for as long as I can remember, and now you throw the visual aspect into the mix. It’s all the things I love in one thing. And I would like to do more of it. But first we have to see if people like this one.

Tagged: FEATURES, interview, INTERVIEWS, jim greer, SPIN DNA