Credit: Getty

When it comes to access to music, this is a golden age. “You have an armada of music at your disposal at all times,” says Manuel Gonzalez, an organizational psychologist at Seton Hall University in South Orange, New Jersey. It would take someone until the twenty-seventh century to listen to the 100 million or so songs currently available on the streaming service Spotify — without ever listening to a song twice, or to whatever is added from now on.

There is also a seemingly infinite number of curated playlists to fit a listener’s mood or activity, claiming to help boost fitness performance, calm the mind or increase productivity. For example, the YouTube stream “Lofi hip hop radio — beats to relax/study to” has nearly 12 million subscribers. Many scientists listen to music while conducting experiments, analysing data and even writing manuscripts. But does music actually enhance productivity in the workplace?

Intricate impacts

Evaluating music’s effects on performance is complex. “Everybody’s different. Every song is different. Every environment in which you’re listening is different,” says Daniel Levitin, a musician and neuroscientist at McGill University in Montreal, Canada, who studies how music affects cognition and perception. Music’s effects vary depending on where someone is, the time of day, their mood, recent interactions and many other factors. “You’re never exactly the same person when you listen to the song again,” says Levitin, who has worked as a music consultant and recording engineer for a variety of artists, including Steely Dan, Stevie Wonder, the Grateful Dead and Santana.

Neuroscientist and musician Daniel Levitin listens to US jazz pianist Bill Evans to focus.Credit: Mike Roelofs

Despite these nuances, scientists have identified how music affects the human nervous system, engaging every region of the brain that has been mapped1. When a song plays, sound waves reach the ear, where the vibrations are translated into electrical signals. These are first processed in the brainstem, which can elicit a startle reflex and a release of adrenaline. Components, including loudness, pitch, rhythm, tempo and timbre, are analysed separately by circuits in the auditory cortex and prediction circuits in the prefrontal cortex. “Then it all comes together about 40 milliseconds later, and you just hear the music. That 40 milliseconds is a lifetime in brain chronometrics,” Levitin says.

While this is happening, regions of the brain involved in the motor system, including the basal ganglia and cerebellum, process the rhythm, often resulting in the movement of body parts as neurons fire in synchrony with it2,3. “The sound comes in through the auditory sense, but it manifests in the whole body — the head, the torso, the arms and the legs all want to move to the music,” Levitin says.

Listening to music releases various neurochemicals, including dopamine, which helps people to pay attention and motivates them to seek pleasurable activities, and opiates, which convey pleasure. According to Levitin, oxytocin, a hormone that can help with social bonding, is often released when people sing or listen to music with others4. And sad music has been suggested to release prolactin, a soothing hormone5. All of these translate to how people feel and perform in the workplace.

Take our poll

Mood modulators

Many people listen to music to regulate their moods, says Karen Landay, a classically trained violinist and management researcher at the University of Missouri–Kansas City. “If I’m getting crabby, I might put something on that cheers me up. If I want to concentrate, I do better with quiet music,” she says.

In 2022, Andrea Caputo, a pianist and organizational psychology PhD student researching the effects of music at the University of Turin, Italy, surveyed 244 workers to evaluate how listening to music for different purposes affected their perception of job satisfaction and performance6. Specifically, Caputo and his colleagues asked workers whether they listened to music to regulate their emotions, as background noise or to analyse the technical aspects of songs. “The emotional use of music is positively related to job satisfaction,” says Caputo, adding that workers reported higher scores for job performance and satisfaction when they used music to regulate their mood at work. This wasn’t the case for workers who listened to music as background noise or to analyse it, according to the study.

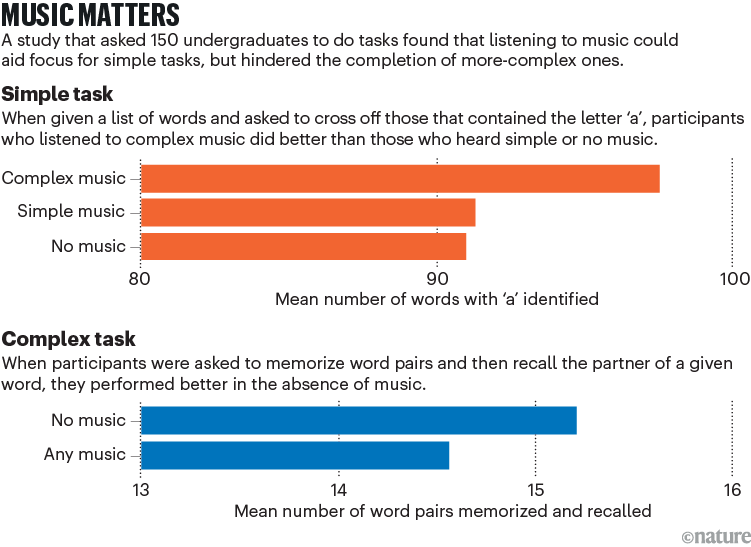

Listening to music can help scientists to perform simple tasks, such as pipetting or data entry, by engaging the brain in a way that focuses attention. “Music might even serve as a way not just to make you more productive, but to also ease some of the unpleasant emotions that can happen while you’re doing routine tasks,” Gonzalez says. But for complex tasks that require a good deal of thought, such as brainstorming ideas or writing papers, listening to any type of music — regardless of lyrics, volume or complexity — can undermine performance, he adds (see ‘Music matters’).

Source: M. F. Gonzalez & J. R. Aiello J. Exp. Psychol. 25, 431–444 (2019).

Music can also affect the breadth of someone’s attention through its emotional effects, says Kathleen Keeler, an organizational psychologist at the Ohio State University in Columbus who studies the pros and cons of listening to music at work. For instance, listening to complex songs in minor keys activates regions in the brain that boost the release of stress hormones, such as adrenaline and cortisol, that prompt negative emotions, she says7. Negative moods are more likely to narrow the scope of a person’s attention, she adds, by enhancing inhibitory control, the ability to focus on a particular goal and avoid distractions7.

By contrast, simple songs in major keys can, through the release of dopamine, induce positive emotions that improve working memory, which widens attention. “You’re more likely to incorporate additional features of your environment into your awareness and use that information to generate new ideas,” says Keeler.

However, the ability to choose what music to listen to, and when, is also really important. “Theoretically, music in a major key should increase your positive affect, but it may not, because it’s not what you need or want at that moment,” Keeler says. “As a consequence, you become more depleted and fatigued at the end of the day, because you’re expending a lot of resources and mental energy on trying to block out that music and manage your emotions.”

Musical mindfulness

Personal preferences mean it is hard to make any specific recommendations as to how researchers can best incorporate music into their working day, but there are some general considerations to keep in mind when using music in the laboratory.

“Save music for when it matters,” says Gonzalez, noting that listening to music is essentially multitasking because it requires regulatory and cognitive resources, which deplete over time. “I use music strategically, by saving it for tasks that are really monotonous,” he adds. Gonzalez listens to heavy metal when doing routine data analysis, but generally doesn’t when preparing tasks that require a lot of mental effort, such as preparing lectures (see ‘My favourite wokplace tunes’).

Gonzalez encourages his lab members to avoid music when delving into new territory, so that they can apply all their mental resources to process what they’re doing and learning. As researchers become more proficient in particular methods, complex tasks can start to feel routine, a better scenario for incorporating music. “I also recommend putting some time constraints in place, or at least taking some time to step away from it, so you’re not listening to music for hours on end,” he says, noting that he often hits a point when he needs to turn the music off because he starts making mistakes and feels mentally fatigued.

The emotional use of music can improve job satisfaction, says Andrea Caputo (left).Credit: Andrea Caputo

Levitin suggests listening to music during breaks instead, to “hit the reset button in your brain”. This is because music activates the default mode network, a network of brain areas that is more active when a person is not paying attention or focusing on any specific task8. When the default mode network is activated, the brain is in more of a daydream-like state, which is needed to snap out of the ‘central-executive mode’ used for problem-solving, decision-making and goal-oriented behaviours.

“If you find yourself losing attention and you want to grab a cup of coffee, it’s your brain trying to tell you you’re depleted,” says Levitin. Coffee doesn’t always help, but using music to spend 10–15 minutes with the default mode network activated can help people to feel better before getting back to work. “It can motivate you, it can relax you, it can centre you.”

One key thing to avoid is playing music to everyone in the lab to encourage productivity. “The notion that there’s workplace music, that somebody’s going to pipe it in, and everybody’s going to respond to it in the same way” is a fallacy, says Levitin.

Headphones are not acceptable in every environment but are a great way to reap the benefits of music without disturbing colleagues. “For some, music does not work, so you need to provide an environment where colleagues can be free of music, even as their neighbours have it,” Landay says. “It just really comes down to the individual and them finding their own preferences and what works best for them.”