This article originally appeared in the October 1989 issue of SPIN.

At 8:30 in the morning, the interview finally over, Terence Trent D’Arby still wants to talk. The English sun, such as it is, has begun to trickle in through the windows of his Knightsbridge townhouse, and turned the streets outside, a quiet neighborhood of “doctors and arms dealers,” according to D’Arby, from a slate gray to the chalky color of a forgotten cup of coffee. Another London summer day is just beginning.

D’Arby’s girlfriend, Mary, and their seven-and-a-half-month-old daughter, Sarafina, have already come downstairs for the morning. “Would you stay for breakfast?” he asks, addressing both me and the CBS vice president in charge of publicity, Marilyn Laverty, who has waited on a cotton sofa throughout the vigil. For the last hour, D’Arby has done nothing but talk astrology and shoot questions about some of his current favorite musicians: R.E.M., Prince, Michael Jackson, Maria McKee, U2. Out of interview mode, he is relaxed, as inquisitive as he is opinionated. “What’s gonna happen next with Springsteen, after that last album?” he asks, and seems genuinely interested in the answer. He does not polish his pearls quite as carefully before sharing them, nor preface them with the disclaimers, “Please don’t think I’m name-dropping, but—” or, “Please don’t think I’m trying to sound hip, but—” that appear so frequently in his interviews. He has a sense of humor. “You can tell I never have company,” he says, “because when I do have guests I don’t let them leave.”

The house is surprisingly genteel, a nouveau-Victorian affair with a giant gilded mirror hanging beside a marble fireplace and mantel out of Town & Country, a monstrous color television, and a rack stereo system on which D’Arby had earlier taped the Stooges’ Raw Power. Over by the baby grand piano are an upright doublebass and a half-size harp, which D’Arby regularly plays for his daughter. Just off the living room is a small office decorated with gold and platinum Terence Trent D’Arby LPs and singles. Knightsbridge, on the southern edge of Hyde Park, is the home of London’s titled aristocracy. Mary found the house while she was pregnant and D’Arby was on the road; when he returned, this was his new home.

Surprised that we’re still here, Mary wears a white floral print robe as she holds Sarafina, a chubby, alert infant with the slightly mottled skin common in children of mixed parentage. “I always keep these hours,” D’Arby says, looking as vigorous as when we’d arrived, at his beckoning, at 3 a.m., after we’d driven to a studio in north London, also at his bidding, to hear his new album, Neither Fish Nor Flesh, in an environment he felt did the music justice. “When I’m working, people have to remind me to eat and sleep.”

Later, holding Sarafina over him in an admittedly self-conscious attempt to play the loving father, he nods at me and says to Mary, “See, how can he slag me off when he’s got his own 11-month-old baby at home?” We have talked, through the night and into the morning, of many things, cosmic and banal, but this theme, this anticipation of a great critical waterloo, has never been far from D’Arby’s discourse. “A lot of people would love to see my big mouth shut.” This is, it seems, his overriding obsession.

When we agree to stay for breakfast, D’Arby turns to Laverty. “Can you cook?” he asks her. He turns to me. “Can you?”

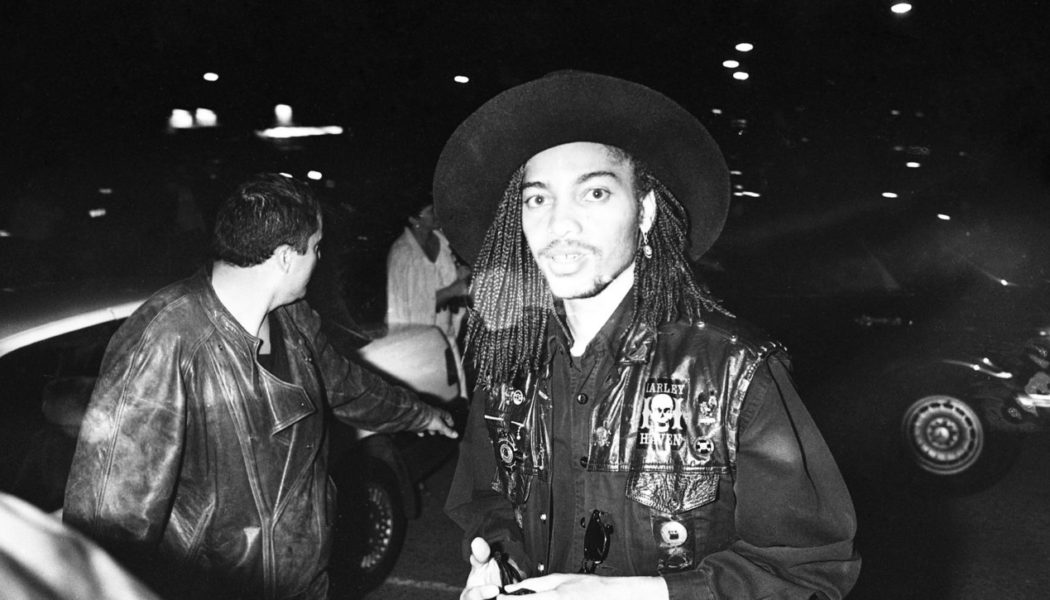

Two years ago, a newcomer with beautiful cheekbones and a suspicious apostrophe, Terence Trent D’Arby introduced himself with the braggadocio of an established superstar. His album, Introducing the Hardline According to Terence Trent D’Arby, he said, was better than Sgt. Pepper’s Lonely Hearts Club Band, and would prove to be, “one of the most brilliant debuts from any artist in the last 10 years.” Beyond that, D’Arby was, in his own words, “a genius—point fucking blank.” An early press release listed as his interests, “reading, films, mysticism and death, and dream analysis.” In the middle of his first lengthy interview in the United States, he announced that he would never do another interview, at least for the next five years.

At 25, D’Arby declared himself a heavyweight, intellectually as well as musically, all the while serving up an album of agreeably light fare. Introducing the Hardline, good as it was in parts, introduced a talented voice and a catchy line—church-trained American singer given a bit of English polish—but never broke the ground that the title promised. Later, he said that he had only made his rash claims to get attention, to create a little fuss at the launch of a career. He was an American in exile, stateless but by no means rootless, taking advantage of the self-blinding English romance with persons and things black and American. He had been playing the media game, and playing it well.

Sitting in the vacant maid’s room of his Knightsbridge home, D’Arby jerks his head from side to side as he talks. His big, skitting eyes are severely sanpaku, showing white beneath the pupils, which in the East tokens an extremely unbalanced, yin, state. “If you ask people what I’m like,” he says, slipping easily into the role of his own biographer, “I’m sure most of them would say, ‘He seems constantly distracted,’ because my antennas are always up. I might be talking to you in a deep conversation, and I’m trying to listen to you, but I’m also trying to listen to something else.”

In his black sleeveless T-shirt and tight black denim jeans, D’Arby is rail-thin, all long arms and legs, without enough butt to make a fingerprint. A tattoo of a skull with a rose in its teeth peeks out on his angular left shoulder. His sharp, handsome features are as striking in real life as they are on television, and the light skin—the inheritance of a mixed white, black and native American lineage—is even richer in ambiguity. A light brown handlebar mustache and goatee make a valiant but ineffectual attempt to lay claim to his upper lip and chin. For all his handsomeness, and his well-documented awareness of it, D’Arby does not pose; the flesh and blood is less sexy but more approachable than the collection of pixels on MTV.

At random intervals he either unwraps or wraps his braids in a scarf, and crosses his legs to sit on his black motorcycle boots (he rides his Harley with Mickey Rourke’s brother, a notion which conjures images of rock stars straddling hogs with various members of the Rourke clan throughout Christendom). According to Laverty—who calls him Terence, but refers to him as Terry in conversation with his assistant and friends—D’Arby is nearly sightless without his glasses. His voice is soft and high, almost effeminate, at odds with the bluster his words carry in print. His accent seems to belong nowhere on God’s earth. “Much to a lot of people’s surprise,” he says, “talking about me and my music ain’t fun. After a while it’s dreadfully boring. And it gets dangerous, because the more bored you become, the more you make shit up just to keep yourself amused. You have to. But you feel cheapened by it. At the same time, I think, ‘What’s lying? Who cares where I was born? What’s relevant?’ I remember at one point, people asked, ‘Is Dylan a fraud?’ My attitude was, ‘Does his music sound like a fraud?’ ”

As he speaks, more self-effacing than abrasive, it is easy to read his bolder past remarks as a well-targeted snow job, a gambit in which he had only a distanced, cynical market interest. That was the hype side, he seems to invite, this is the real me. “When I’m being Mr. Hype, I’ve almost got a different head on than when I’m actually talking as myself.” In an interview, with the tape obviously rolling, it’s hard to know how to take this remark, as a profession of sincerity or insincerity.

But there’s something more to D’Arby, a side that’s overly earnest and even nerdy. As offhand as he tries to be, D’Arby has much more than a sporting interest in the media. After Michael Corcoran wrote an appreciation of D’Arby in the June 1988 issue of SPIN, D’Arby sent him a note of thanks for, “the piece that you so kindly wrote concerning me.” The note, signed with an ideogram in which the author’s name described the outlines of a face—just the sort of thing junior high school girls strive for but never get quite right—closed with D’Arby’s wishes that, “hopefully I won’t let you down in the future.” Clumsy and formal, it was a small offering of humility given freely, without an audience. It also showed another aspect of D’Arby: a little geeky, a little uncomfortable, more beholden to the press than eager to manipulate it. In a few stilted words, he revealed more of himself than he had in any of his blustery and eminently quotable marathon interviews. The self-proclaimed genius, a new rock sex symbol whose first album, made on a small budget, had sold over 6 million copies worldwide, really did care deeply about what a few critics thought, and about the legitimacy they conferred. D’Arby’s plastic talent for reinventing himself as a pop icon, with an image and a place in the pantheon intact, had made him almost inhuman; the awkward little note went a long way toward making him human again.

“I have a destiny,” D’Arby says, following his own lead in the middle of this unreasonably hot July night. “What is my destiny? How big is it? I’ll just have to wait—you’ll just have to wait and see. My destiny is not something that I can sum up in two pages. I think I know what it is, but some things are better left unsaid. I’m not saying this to take the heat off me, but I think there are a few of us around who will be used for something.

“Martin Luther King wasn’t an accident, Gandhi wasn’t an accident, Dylan was not an accident. Dylan was the drum major for a social movement. Those people who are destined to be read about in 2,000 years’ time are those that were in the right place at the right time. I believe that the guy who drives a cab up and down the street perhaps has a lot more free will than Gandhi had. Gandhi’s life was probably for the most part predetermined.

“Why did I survive four or five close brushes with death if there wasn’t something meant for me to do? I could say things to you that would prove prophetic later. I say that with confidence.

“Some people,” he concludes, “have more destiny than others.”

Terence Trent Darby was born, without an apostrophe, on March 15, 1962, in Manhattan, the first of six children. His father, the Reverend Benjamin James Darby, had been a minor league baseball player and something of a rock’n’roll guitarist before he heeded the calling to be a Pentecostal minister; Terence’s mother, Frances Darby, was a substitute teacher and gospel singer.

The family moved around a lot, from New York to East Orange, New Jersey, from Florida to Chicago, before settling in DeLand, “the Athens of Northern Florida,” a college town about 18 miles southwest of Daytona Beach; the Reverend Darby is now pastor of DeLand’s Church of Our Lord Jesus Christ and chairman of the Pentecostal International Board of Evangelists. His father never allowed any television or secular music in the home, so Terence used to sneak away to hear pop and country music, and hid a small transistor radio in his bedroom. When he heard the Jackson 5’s “I Want You Back” spilling out of a neighbor’s home, he has said with daunting regularity, “It was Saul’s conversion to Paul” (in which, after meeting Jesus Christ, the apostle told Saul, “Don’t you know? He’s just like us”). This anecdote, like many from D’Arby’s past, is by now so well-polished that water would run right off it.

D’Arby sang in his father’s church from the time he was 6 until his adolescence, when he rebelled against his upbringing. He continued in the school chorus, the Sound of the Seventies. “Every time I sang I’d get a standing ovation. I came to expect it after a while. I became the most popular guy in school because I sang. I started writing for the paper. I wound up being managing editor. I was president of the civics class. Definitely nerdy shit. I never claimed I was James Dean growing up.

“All that changed one day when this kid who was much bigger than me was beating the shit out of me. I was the guy who used to get beat up every day at school. I had a big Afro then, and I had this black Afro pick with a metal tip. And I’ve never been a violent person—I know that my boxing contradicts that, but it’s true. But he was on top of me, really knocking the stuffing out of me, and I just stabbed him with it. It was enough to make him yell and jump off me real quick. I got suspended from school, and after that my world crumbled, because I got kicked out of this, kicked out of that, and I quit the Sound of the Seventies. I went from being this completely unknown quantity to being Mr. Popular, to going back to an unknown quantity.”

D’Arby likes to draw his high school years as an unhappy period: he was the scrawny boy everyone picked on, the light-skinned black who was rejected by both races. “I was too perceptive when I was a kid. I picked up on shit I shouldn’t have picked up on.” One of his strong ambitions as a pop star, he has said, again on many occasions, is to rub his success in the faces of the folks back home, to show up at his class reunion in a limousine, with a bimbo on each arm. But D’Arby was also a joiner, an active member of many school clubs, and a finalist in the Mr. DHS contest, which commends the most popular and talented boy in DeLand High School’s graduating class.

“I went through a period of time when I had a problem with both white kids and black kids, for different reasons,” he explains. “I just said, ‘Fuck the both of you. I’m green.’ I went through a phase when I was a very militant person, very militant black man, around my mid-teens. It coincided with my very pretentious budding intellectual years. Before that, I went through the I-want-to-be-white syndrome, to just wish that I was treated like I saw white people treated. But that’s when you’re young and naive, and you don’t know what you’re talking about. I say that because whatever I was meant to do in this world, I was meant to do as a black person, or I wouldn’t have come back as this. Somebody said, ‘I got something for you to do, and I want you to do it as a dark-complexioned person.’ “

In 1976, when Sugar Ray Leonard and the Spinks brothers won Olympic gold medals in boxing, raising the sport to a level of excitement and prominence it had not known since Muhammad Ali’s prime, 14- year-old D’Arby found a new passion. “I got into it by accident,” he says. “Me and my cousin one day went into the laundry room and just started piling all these white socks on our hands. I found I could hit him really easily. So my dad bought me some boxing gloves. He didn’t consider boxing fighting. Two weeks after I got the gloves a guy across the street called me out, and I hit him with a jab in his forehead, and he just went out.”

The D’Arby biography, as he tells it, in huge, sweeping chunks, scans a bit like a paperback spy novel: the opponents all seem a little too formidable, the challenges too dangerous, the victories too decisive. It is as if his most desperate fear is to be caught being ordinary—not in the lofty munificence of confessing his own fallibility, which after all only reaffirms his higher status, but maybe in the acknowledgement that his talents from time to time had their match. “As regards my bio,” he says, “if I wrote 10 things, all of them are true. Some things are exaggerated, because… Why not?”

The roots of an 80s rock star, D’Arby’s past is his to invent, but the construct he has developed, resolutely unequivocal, is not porous enough, giving enough, to make him really intriguing. In the absence of mystique, the pressure is on D’Arby to continually pitch good copy, and his speech labors under it. He plays the role of the precocious child, living only in a constantly changing present.

After the Olympics, boxing became his life. It was one of several times when he completely made himself over into something he previously was not. He began training a couple days a week at a gym in Orlando, and stopped singing altogether. He became a local Golden Gloves champion, attracting the attention of Army boxing coaches. When he finished high school, he wanted to join the Army to box, even though he was only 17; his father refused to sign a release, and persuaded him to enroll in the University of Central Florida, near the gym in Orlando, on a scholarship. Drawing on his background in the school paper, D’Arby settled in to study journalism.

“I was rooming with my cousin off-campus. He was the starting tight end on the football team, and there were cheerleaders in and out of my house like it was nothing. Because we were living away from our parents, we were both eligible for food stamps. We’d fill our place up with food, and all of the football team would crash at our place. I’d be cooking for them. They’d bully me about.

“The frustrating thing was all these cheerleaders, and I was getting none of it. When you’re 17, you’re just discovering what hormones are about. Apparently there was a survey that said that men think about sex every eight seconds. I imagine when you’re 17 you think about it every .65 seconds. And you know what cheerleaders are like; they’re gorgeous. They’re there. And I’m being kicked out of my room by a linebacker or something. You think out of sympathy one would come my way, but it didn’t work like that at all. I was frustrated and I was distracted, because I’m sitting in class behind this girl who that morning came out of my room, and she wasn’t with me.”

He dropped out of college after a year, and again made himself over; on July 30, 1980, four months after his 18th birthday, he joined the Army. “There was no options there for a black or white kid beyond flipping hamburgers. I wanted to continue boxing; I was thinking about turning professional. Also, it was a way to get away. In retrospect, if one was to believe in destiny, that was something that obviously had to happen, because it brought me to Germany, and otherwise I wouldn’t have come here.”

He was stationed first at Fort Sill, Oklahoma, before being shipped to a post near Hamburg, Germany, with Elvis Presley’s old outfit, the Third Armored Division. He soon gave up boxing altogether. “What got to me was getting up at 5 o’clock every morning and running. I just thought, ‘What sane person gets up this early?’ So I stopped. I said, ‘This is not for people who have brains and options.’ ”

Residents of northern England often speak of the American servicemen stationed there after World War II as gods descended to walk the earth: robustly healthy, uniformed, bringing a new music and a new social dynamic. Black American soldiers, an increasingly redundant term, were largely responsible for the international spread of rhythm and blues in the 40s and 50s. They were the avatars of a new sensual age, ideal “savage” icons for liberal European imaginations. In Germany, where the archival study of US black music is a national pastime, D’Arby found a niche. One of many talented young singers in DeLand—his closest friend from the Sound of the Seventies went on to be a professional opera singer—in Germany D’Arby was suddenly the real thing, an import the nation could never hope to manufacture on its own: black, beautiful, with a Pentecostal gospel background and a uniform full of attitude. After years of not singing, he joined a local funk group, he says, “to get the attention of a girl.

“All my life,” he says, “I’ve been a square peg trying to be forced into a round hole. For an 18-month period I suspended disbelief and just went along with the Army program. I was a supply specialist: ‘Here’s your sheets, what’s your number?’ I allowed myself to become brainwashed.

“When I woke up, I woke up hard. I woke up screaming and kicking. I hope this doesn’t sound elitist, but I realized that I was tired of being told by a person with a fourth-grade education what to do all the time. I think I broke the record (or Article 15s, official Army reprimands. And I didn’t care. I was almost like an anti-cult hero, because I was just reckless and didn’t care.

“Once I stumbled into this band, my mission in life woke up again. I remember feeling very much one page of my life turning and another chapter beginning.”

Singing with a nine-member group called Touch, D’Arby distinguished himself for his ability to sound like Michael Jackson, whose Thriller album was at the time in the middle of its campaign for world domination. D’Arby became a hot attraction, and went AWOL—a very high-profile AWOL, performing regularly in clubs—until he was discharged from the Army, under circumstances that he has toyed with and greatly romanticized over the years, on April 15, 1983. He was 21. He returned to the states long enough to get processed out, then rushed back to Germany.

Terence Trent D’Arby is a soul singer only in the way that Mick Jagger is an R&B singer: heavily mannered, with a rock’n’roller’s appreciation that sometimes mannerisms can be everything. After a childhood of gospel hymns and the popular standards of the school choruses, he learned about soul music in Germany, in listening sessions with his then-manager and mentor, Klaus Pieter Schleinitz, a music business hustler generally known as KP. It was another makeover: this time from a Michael Jackson-style entertainer into an honest-to-God, gospel-shouting soul man.

“We’re not our pasts,” he says, “and I’m not really the person that made The Hardline, but that person is related to me. If we are to believe in our coming from past lives, and choosing the situations we’re going to come back to and choosing our parents, I can see why I chose that environment in which to grow up. It gives me a past to draw from, which I’m now doing. But you are not your great-great-grandfather. You are not the person you were five years ago. That’s a person that you know. That’s a person that you have a connection with. But you are not that person. One can allow the past to chain one. But that is a no-win situation.”

When D’Arby sings Smokey Robinson’s “Who’s Lovin’ You” or Sam Cooke’s “Wonderful World”—or any of the soul ballads he routinely trots out for television appearances—his performances reflect more on him than on the songs. They are like the old-fashioned chrome microphone that is his only stage prop: claims to a dead language safely buried in the past. They are soul performances for people who cannot hear the music of Alexander O’Neal or Luther Vandross, performances drenched and shimmering in the authenticating waters of nostalgia. They are theater, great rock’n’roll theater, only barely playing at being anything else. And D’Arby pulls it all off with incredible grace. The soul stylings formed the backbone for his debut album, Introducing the Hardline According to Terence Trent D’Arby.

“I remember someone asked me why I always seemed like I had a chip on my shoulder,” he says. “Sometimes you hate it when people who don’t know their rock’n’roll history ask you dumb questions. You’ve gotta know your rock’n’roll history if you’re gonna be a music journalist. And if you know your history, you know that the greatest rock’n’roll, especially in the early days, was made by people who had chips on their shoulders, who had something to prove to somebody.”

Two years after Introducing the Hardline, D’Arby has reinvented himself again, not as a singer this time, but as an artist. His new album, Neither Fish Nor Flesh, due out in mid-October, is a showcase of creative ambition, with D’Arby’s talents doing their best to keep up with his adventurousness. “I’m not trying to disassociate myself from the first album, but it’s almost like it didn’t really register. l can’t look at that as a turning point in my life, a new chapter opening, because I didn’t feel it. This past year, I did. My first album existed purely to lead up to this one. I couldn’t just come out into the cold with something like this, having had no history. So that album existed to give me a name and a profile and put me in the driver’s seat so that when this comes out, it does what it’s supposed to do. I quite frankly feel that this album will explode. And when I get that feeling, I’m not wrong.”

When he was in California last year, he got into a conversation about the Beach Boys’ experimental album, Pet Sounds, which he had never heard. After the conversation, Marilyn Laverty, who had also been involved, bought him a copy of the album; when she gave it to him that evening, she found he had already bought a copy of his own. For the next six months, he played it every day, at least once a day.

Neither Fish Nor Flesh, conceived in the middle of D’Arby’s 60s obsession—he has recently become friends with Pete Townshend, and sang on Brian Wilson’s solo album—echoes Pet Sounds’ relentlessly inventive arrangements, patched together with D’Arby’s straightforward a capella gospel shouts. The people at Columbia in Europe, he says, delight in its boldness; the people at Columbia in the US call it ambitious and worry about its commercial prospects. The album is, if we can believe D’Arby, a masterpiece.

“People keep telling me that this record took a lot of courage, and I tell them—it’s no attempt at humility—that it wasn’t brave or courageous. I merely did what was given to me to do. Now, before you ask, ‘Does that imply that you feel it was given to you?’ I can’t really describe it any other way. Everyone who worked on the album, whether it was my cook or the roadies, all of us went through some type of transformation. I don’t necessarily think it was coincidence. I am in the best position to tell you what happened, and I can tell you that I was very much a channel by which things came through.

“The way it came together so easily, somehow I don’t think selling it will be difficult at all. I can’t help but think that whatever was pushing the shit through me, the force by which I felt these things coming through wouldn’t just come if it was meant to be shipped back to CBS by Tower Records.”

As we conclude the interview, D’Arby, who has given away very little, says, “I feel like I should have been on a couch.”

At breakfast—an assortment of tropical fruits and a frothy blender concoction, all prepared by Mary, who does not eat—D’Arby plays with Sarafina and continues to talk affably, largely about astrology and palm reading, the effects of the moon on our bodies, and what a great time the 60s were. At one point he interrupts Laverty to correct her language. “Never say punk rock,” he tells her, the precocious kid to the end, “if you were there, you just say punk.” With his English accent and funky braids—real, by the way, to all appearances—he sounds almost convincing, glossing easily over the fact that Laverty’s husband had launched New York Rocker, one of the early punk fanzines, and never mind where Terence was in 1977.

By 10:30, the London Sunday scandal sheets are already on the doorstep, and D’Arby’s energy is the only left in the house. His flight for Paris and a European media blitz leaves in five-and-a-half hours. As I make my way out into the empty Knightsbridge streets, D’Arby says, “The guy who wrote the other story—tell him thanks.”