Great artists use their talents to blow minds and fill up hearts. If you can’t do that, change your course or leave the room. But assuming you’ve already got those bases covered, can you predict the future? What would you call a band who made significant sonic advancements, refused to hide their sexuality and fomented a mindset of creativity sans fronteres that succeeding generations are copping as their own? We’d call them Coil.

In the mid-‘80s, the duo of Geoff Rushton (aka Jhonn Balance) and Peter “Sleazy” Christopherson teamed to create their own idiosyncratic zeitgeist in the realm of industrial music. The latter was a polymath that was part of the legendary unit Throbbing Gristle, who used the i-word to describe their sonic mutations that were often regarded as both compelling and revolting. The former was a tireless multi-instrumentalist, underground music enthusiast, poet, writer and fanzine creator who first became acquainted with Christopherson as a fan of TG. The two became members of Psychic TV, the aggregate chaired by frontman Genesis P-Orridge after TG’s demise, and would leave the band in 1982 to pursue their own vision under the banner of Coil.

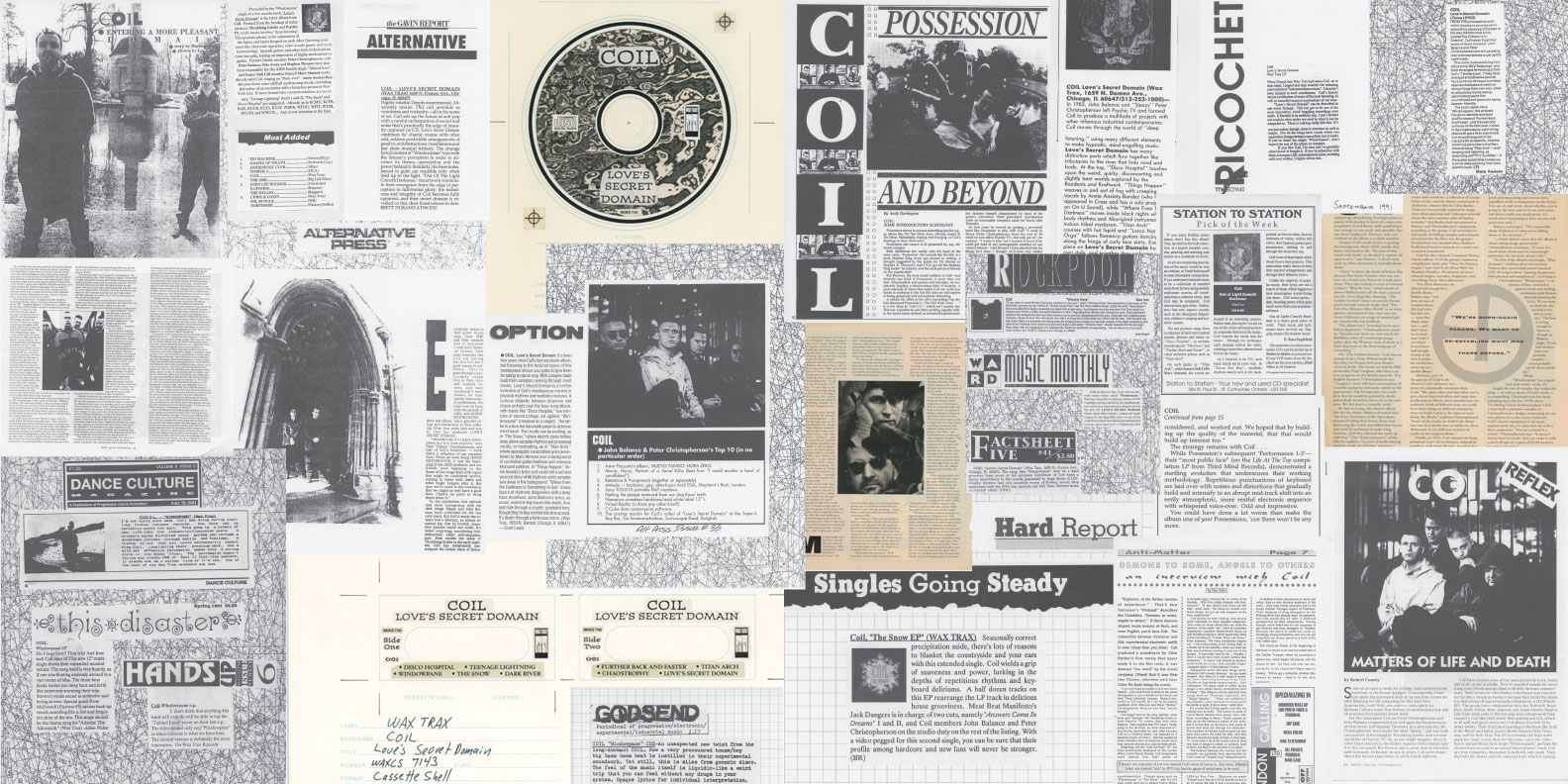

Uncompromising from the very beginning, the duo gained recognition via a morose, anguished cover version of “Tainted Love,” recorded as a response to the AIDS epidemic ravaging the world. Coil’s first full-length releases Scatology (1983) and Horse Rotovator (1984) helped define many of the aggressive aspects of industrial rock, the underground movement fostered in America by the Chicago-based record label Wax Trax!

“They were just really nice people,” recalls Al Jourgensen, majordomo of Ministry, the label’s flagship act. “[Jhonn and Sleazy] showed up at all our shows in London. They were some of the few people in that arty community who liked me. Throbbing Gristle took me under their wing when I was just a snot-nosed little American punk. Later on, Peter directed the videos for ‘Over The Shoulder,’ ‘NWO’ and “Just One Fix.’ Just super-talented and super-sweet people.”

“I think that there was no precedent for Love’s Secret Domain, really,” opines Chris Connelly, the Chicago-based singer-songwriter and former Ministry/Revolting Cocks singer. “It really sounds like no other record to me. But there were records that came afterwards that borrowed heavily from that, I think. It was using electronic music not to necessarily fill a dance floor, but there were the same kinds of sounds.”

“It’s obviously Coil’s masterpiece,” says Ryan Martin, co-founder of Dais Records, the label which has several Coil reissues in its catalog of assorted electronic and post-punk releases. “No one in their circle was doing something that ambitious. Looking back on LSD, it’s an ambitious cinematic record that acts like a movie, where I don’t think the other albums certainly do. It’s well over 30 years and I still have no idea how they made that record. Out of all the Coil albums, I’m definitely the most fascinated by it. And it’s a pretty polished record—as crazy and psychotic as it is.”

Now a new generation of listeners may experience Coil’s milestone release with the special 30th anniversary edition of Love’s Secret Domain. Carefully remastered by Josh Bonati and lovingly presented by Wax Trax! in a variety of formats, Coil’s third album has retained its own cultural cachet. It has influenced consecutive legions of musicians (in)directly, cultivating its own aesthetic consciousness long before succeeding generations armed with software and naivete flipped the term “no-genre” into mere marketing copy.

The backstory of Love’s Secret Domain is filled with circumstances that would drive most projects over a guardrail and headfirst into the ether. From the libertine hedonism that inspired it to the troubling circumstances of its initial release to the steps taken to bring it back into the world again three decades later, LSD is a record that’s overdue for re-examination. It’s been refurbished for the diehards who were there at its 1991 release, presented to a new generation of music fans hungry for its sonic manna and made available through ways and means that take bootleggers out of the equation. Even if all that activity might piss off Coil’s highly protective legion of fans.

“It’s the record’s 30-year anniversary,” says Julia Nash, Wax Trax! president and daughter of late label co-founder Jim Nash, the man responsible for first releasing Coil records in America. “So why not give it the love it deserves, you know?”

During the 1990 recording sessions in London, Coil—Rushton, Christopherson and multi-instrumentalist Stephen Thrower—and producer Danny Hyde enlisted a battery of associates to assist them in the making of their third album. New collaborators as laconic chanteuse/On-U Sound artist Annie Anxiety and Charles Hayward (solo artist and acclaimed drummer for This Heat) took their place alongside perennial contributors Marc Almond (Soft Cell, the Mambas) violinist Gini Ball and vocalist/guitarist Rose McDowall (Strawberry Switchblade, Spell, auxiliary member of Current 93 and Psychic TV). These days, writers and cocky/noticeably high musicians are fond of using nomenclature like “next-level shit” to describe their current projects. The members of Coil had no need to make trite lines of demarcation as their primary goal. They merely knew what they did not want to do.

“One misconception that irked both of them was to be tarred with a clichéd ‘post-industrial’ brush,” Stephen Thrower tells SPIN over email. Thrower is a multi-instrumentalist who joined Coil in the summer of 1984 and stayed until February 1993. “You know, ‘dark lords of decay’ and all that goth-industrial malarkey. In person, they were both very witty, lively and funny, and they hated the pomposity that went with the ‘dark side’ image. Geoff in particular had a manic sense of humor and a joyful streak of the absurd. The cliché was a bad fit even for Throbbing Gristle, who started the whole industrial thing. There was such a dry sardonic wit to TG, an impish streak, and that manifested in Sleazy’s work. He would play me things that would make me burst out laughing—musical ideas, not lyrics—tunes that were so absurdly bright and bouncy or so warped and twisted and peculiar that you would have to laugh.”

Coil’s true strength is measured by their considerable output, always striving toward expanding the parameters of the genre. As a mission statement, LSD works as a means of refracting possibilities instead of mere precious flexing. Often bands will amuse their egos with genre exercises. By comparison, Coil was genuinely a clearinghouse of ideas that was more fascinating than academic. And while the Wax Trax! was certainly the clubhouse for the then-burgeoning electronic/industrial rock movement, Rushton and Christopherson didn’t have much interest in “rocking out” down the same paths as many of their labelmates.

LSD is so teeming with sonic discoveries and genre premonitions, hindsight makes plausible arguments that Rushton and Christopherson’s bloodlines were connected to Nostradamus or that they had perfected a time machine to bring their discoveries back from the future. The opening “Disco Hospital,” is a cocktail of ‘60s easy listening with vocal parts created with that byproduct of digital recording known as the glitch. Ten years later, Daft Punk would take it to the bank (“Face To Face”), hip-hop producers mined it, and the technique has been fully assimilated in today’s hyper-pop scene. (And if we’re really splitting hairs, that ersatz ‘60s jazz organ predates the early-‘90s, non-rock, “space age bachelor pad” revival by three years.)

The ambiance of “Dark River” is truly a defining moment within the dark-folk realm, melding then state-of-the-art digital synthesis shoring up the lyrical hammer dulcimer samples. You can hear a similar nature vs. machine aesthetic at play on “Ice Age,” the track from Trent Reznor and Mariqueen Maandig’s project How To Destroy Angels (the band named after Rushton and Christopherson’s first EP release under the Coil banner). When rave culture began to rise in the UK, the duo found themselves attending those electronic-music-based gatherings. The experiences were distilled into “The Snow,” their take on percolating techno, one that’s been cited as a classic by both EDM headz and beard-stroking aesthetes alike. Many of the dark ambient artists operating today have cured their creative asthma by huffing the ether Geoff, Sleazy and Thrower conjured on the dark, brooding “Chaostrophy.”

But Thrower feels these comparisons don’t necessarily constitute evidence of Coil’s influence. He hesitates to plot direct lines of imitation, flattery or abject theft from bands and artists operating today who may (not) have purloined something from Coil’s legacy.

“The water is muddied nowadays because there’s a disconnect between ‘cutting edge’ studio technique and conservative musical form,” he begins. “Producers learn tricks from adventurous bands or develop new techniques for them, but their next ‘gig’ is with some bland pop diva and they simply port over the techniques they’ve learned working with interesting artists. The result over time is that strange and unusual sounds and production processes are now ten a penny, splattered across fairly dull songs.

“Of course, there are some artists who combine adventurous production and songwriting skills,” he continues. “Listening to Sophie with Ossian [Brown, former Coil member and collaborator/life partner with Thrower in Cyclobe] recently, I could hear echoes of places and spaces that Coil traversed. These New Puritans sometimes sound like they’re traveling through similar terrain, but in their own vehicles and with their own sense of direction. Further back, when the Mego artists [the label started by the late Peter Rehberg] emerged in the ‘90s–Farmer’s Manual, General Magic, Pita–Geoff, Sleazy and I all felt a kinship with their approach to sound. They seemed to have their own take on the ‘ketamine alien vistas’ we were so fond of.”

Wax Trax! label manager Mark Skillicorn thinks that while Coil’s nuances were truly unique, they had that inevitable burden that goes along with it. The old adage of “The settlers get the land, the pioneers get the arrows” rings loud and clear.

“I think it’s that way with anything,” he says. “You have people that are way ahead of the curve. It just takes time for people to catch up. And then it does become an issue. Look at punk rock or anything that’s any kind of real art form to begin with. Coil were doing something that was so ahead of the time and so experimental, it was inevitable that the fringes would come into the center at some point.”

Interviews with Balance and Christopherson from that era would find the duo dropping references to everything from Argentinian tango master Astor Piazzolla (which would explain that genre mutation found in both versions of the LSD track “Teenage Lightning”) to designer drugs. Never fashionably esoteric, the Coil braintrust saw themselves as a conduit for this curious information.

“Something that Coil did—that was brought across from Sleazy’s work in Throbbing Gristle and Psychic TV—was to incorporate pointers to other areas of culture, whether influences or just pleasures to be shared,” says Thrower. “There was nothing didactic: It was in the spirit of shared information, at a time when access wasn’t as simple as clicking a mouse! People with esoteric or magickal interests are sometimes characterized as secretive or elitist. But even in this aspect of their lives, Geoff and Sleazy were inclined to share pointers and make suggestions for further study. It was borne of a desire to spread the widest possible influence and speak to kindred spirits. We were voracious readers, listeners and film viewers. If we came across something special——like Astor Piazolla for instance—we’d mention it in interviews or sleeve notes.”

This reality flies directly in the face of some Coil fans who perceive the group as a rarified talisman for surly intellectuals with more books and records than friends to share and discuss them with. Paul “Bee” Hampshire (formerly of Psychic TV, Futon and Getting The Fear) had been close friends with Geoff and Sleazy months before the duo left PTV all the way up to their respective deaths in 2004 and 2010. He echoes Thrower’s position that Coil’s m.o. was about sharing the wealth of information and culture that piqued their interests. And he genuinely feels sorry for those fans who simply don’t get it.

“There are a couple of things that I do see with some of the Coil fans,” Hampshire says with a touch of regret. “They lose a lot of the love that I think Coil had. They can be quite malicious and vindictive, especially with each other, if they reference the wrong thing. There was a time where I would be a member of a Coil group on Facebook. But now I never go anywhere near those because there are a lot of trolls. Coil were never trolls in that respect: There was a lot of encouragement that they would give to other artists and people in general. And I think that goes over the head of a lot of the fans. They don’t see the aspiration, the love and the humanity in Coil. I think that got lost and it would be great if it didn’t.”

As Thrower has stated, Rushton and Christopherson were far from dour miserablists, even if some of their music felt positively opaque in its darkness. He says that after releasing Horse Rotovator and its companion outtakes LP, Gold Is The Metal, Coil began work on an LP called The Dark Age Of Love, which was tabled then eventually abandoned with some tracks ending up on LSD. The song “The Dark Age Of Love” featured Almond on vocals and Hayward on drums but did not make it onto the final album. (It’s included as a bonus one-sided seven-inch single in the box set version of the reissue.)

When it came time to finally decide on a title, the group cheerfully chose a name whose anagram would be the three consonants closely related to the world’s most legendary hallucinogen. As well as the climate the recording was made under.

“By the time we began LSD,” Thrower begins, “we were all heavily steeped in ecstasy, acid, speed and cocaine. The party never ended–until it did. There was a will to push things to the max in search of extreme and exotic experiences. For a while, you feel that you are making all the choices, until one day you realize you’re not the driver anymore. The miracle is that Sleazy was able to hold down a day job making pop videos and commercials. He didn’t have the luxury Geoff and I had of spending the day in bed recovering! He had such a ferocious and dedicated work ethic; he would never have allowed drugs to compromise it.

“To be fair to Geoff too, he didn’t just use drugs for hedonism,” he continues. “He wrote copiously while tripping, drew hundreds of pictures, painted and experimented with different media and produced some fantastic work. There was a seeker’s attitude to the ‘derangement of the senses,’ a journey of the mind, as well as the body.”

“It’s public knowledge that they were really messed-up on drugs when they did it,” says Connelly of the sessions. “ I don’t think the decisions they made on that record would have been made by a sober, well-rested person. I think they had to be made by someone whose brain was completely at odds with reality. And they captured that.”

Refreshingly, neither Rushton or Christopherson actively sugarcoated anything. In David Keenan’s book England’s Hidden Reverse, the duo acknowledge their pleasure-at-any-cost activities in their own words. But it was all integral to the music they were making.

“If you call it ‘drug-fueled,’ it’s hard for people to understand,” Hampshire says. “I think it’s simplified. Are shamanistic rituals in the Amazon drug-fueled? Not really. Drugs are part of the equation, but if you say it’s drug-fueled, people think they’re doing it because of the drugs—which they’re not. That was just one aspect of what was happening.”

“It’s a fantastic book,” Dais’ Martin acknowledges about Keenan’s tome, which was culled from extensive interviews from Rushton and Christopherson, Current 93’s David Tibet and Steven Stapleton of Nurse With Wound. “You’re hearing it from them when they were alive talking about it. It was no secret that Geoff struggled with schizophrenia and things like that. Coupled with monumental drug and alcohol abuse, you’re going to get some amazing art.” He pauses. “But I wouldn’t want to have been around for those sessions.”

Here in the 21st century, same-sex couples and LGBTQIA+ initiatives are far more prevalent and accepted than they were when Coil began. While Rushton and Sleazy felt no pressure to purposely hide their relationship, they never leaned into it as an angle to gain attention to their work. Coil fans were hardly frightened by the glans-side-up erection rendered on LSD’s cover. Publicly acknowledging their sexual orientation at a time where rampant homophobia was sweeping across ‘80s Great Britain was a dangerous prospect. Thrower says that support for the group from Britain’s gay community was frustratingly scarce and begrudging at best.

“State- and press-sanctioned homophobia was rife here in the 1980s and 1990s,” Thrower recalls, “and it fomented a fury in us, as in many LGBT people. National newspapers would openly deride gay people using slurs as frontpage headlines. And all in the face of AIDS, when we were seeing friends and lovers die. We were never backwards in coming forward about this. The realization that you were so profoundly at odds with the wider culture gave your purposeful disconnection a real edge of loathing.

“On the other hand, one thing that I know was very disappointing and infuriating to Geoff and Sleazy was the lack of support or interest in the gay press,” he reveals. At the time, high-profile publications as Gay Times, Pink Paper, QX and Attitude hardly ever paid any attention to Coil. Even when Coil played the Queen Elizabeth Hall in 1999—a massive and prestigious event in the heart of London—the gay papers and magazines barely grunted. They would salivate over straight pop musicians who ‘daringly’ let it be known they were ‘down with the gays,’ but they couldn’t be bothered to cover a queer band who had never been anywhere near the closet, never mind in it!”

In sharp contrast to Thrower, Hampshire sees Coil’s relationship within the gay community much differently. The group were still very much an acquired taste. In those days it was accepted that no habitue of gay nightlife was ever going to hear a Coil track after a dance remix of a hit Whitney Houston single.

“No, we weren’t,” he agrees. “The gay scene was pretty naff as a rule, in the ‘80s. I don’t think [Geoff and Sleaze] would be naive that they would expect the gay community and the gay press to understand what they were doing, even if the gay press were to write ‘This band are amazing, amazing, amazing.’ It’s still not going to get any traction. They’re not going to get played in gay pubs and bars. So it’s flogging a dead horse. And I think they knew that straight away. They didn’t set their sights on that at all.”

Hampshire also posits that if Coil were looking for any kind of “in” with that community, they certainly had one. Larry Steinbachek (RIP), who played synthesizers in acclaimed gay electro-pop trio Bronski Beat, lived with Rushton and Christopherson in Chiswick for a period in the ‘80s. “They were the ultimate young gay band,” Hampshire opines. “So if Coil had wanted to pursue any of that, they would have made more moves to make that happen. I’m assuming they were not interested in that, really.”

The 30th anniversary of LSD arrives at a time when interest in Coil seems to be significantly expanding. Dais Records reissued Time Machines, the group’s 1998 drone-based album and their 1999 release Musick To Play In The Dark. But there are still some inescapable holes when it comes to the group’s discography. The first two Coil albums, Scatology and Horse Rotovator, remain out of print. And in 2015, a series of eight limited-edition LP-length compact discs featuring period-era singles, compilation tracks, alternate mixes and demos—all culled from Christopherson’s archives—were withdrawn as fast as they had entered the marketplace. Rumors abound as to the nature of the precipitous psychic black cloud that seemingly follows the group’s back catalog.

Dais’ Ryan Martin is thrilled about Wax Trax’s reissue (“The world definitely needs it”) and he says Thrower’s participation “lends it to have that true authenticity because that record is very much him. ” He says that the shifting lineups of the surviving members of various eras of the group makes licensing some titles murky. “Coil was like a shifting lineup constantly. And with certain older albums, maybe not even [the band] had the rights to them. Maybe someone that was involved in [those records] doesn’t want them to get reissued.”

Fortunately, Nash and Skillicorn weren’t bogged down with that concern. Wax Trax’s anniversary treatment fulfills two major agendas. The first is obviously getting this special work back on the radar of both diehard fans and generations of new ears. LSD was recorded on digital audio tape (DAT), the format that was then setting a new recording-industry standard. Fast-forward to the 21st century and there have been repeated horror stories about master recordings being lost to the fragile format’s shortcomings.

Highly regarded mastering engineer Josh Bonati built his reputation working on a breadth of different projects while having an understanding of the aesthetics involved with each recording. He was able to frame LSD into a realm that sounds exact and vivid, metaphorically placing listeners into Coil’s multi-layered ear movie. “The great thing about Coil stuff is that their production was really, really good,” he stresses. “Coil was not a lo-fi band at all. You’re starting off with a really good chance of sounding good as a reissue because most of the original versions on most of the record sounded really good to begin with.”

The second agenda is getting the sense of a “do-over” for the legacies of both the label and Coil. When LSD was intended for release in 1991, Wax Trax was in a quagmire of bad circumstances. The label was in the midst of bankruptcy proceedings with no money to invest in vinyl pressings or marketing. Label co-founder Jim Nash was diagnosed with AIDS and had to address his health.

“That was right when the label started to fall apart in a way to where I don’t think [LSD] was ever really released properly,” says Skillicorn. “So the label had to cut corners on certain things, like only being available just on cassette and CD. And it’s a really important record.” Skillicorn says back then, plans were made for the label to reissue the two previous full-length albums. “There was definitely a plan to expand [the relationship] with the band,” he reveals. “It was one of Jim’s favorite bands. It was really important to him and Dannie [Fleisher, label co-founder]. But the timing was terrible. I mean, just terrible.”

In late 2019, Skillicorn and Nash reached out to Thrower to discuss licensing the album and giving it its proper due. “The point was to go back to the original [body of work] and give it that respect it should’ve had from the beginning,” says Skillicorn. “This was really thought through. Julia and I talked about it for a long time. We talked with Stephen Thrower. There was a lot of preparation for this.”

As Coil’s fandom is truly legion, there have been more than a few devotees who have taken upon adopting a righteous position of “protecting” the legacy of their late heroes. Not surprisingly, both Wax Trax! and Dais Records have been scrutinized on the internet by fans long on hubris and short on music business protocol.

“It’s a fine-toothed comb [the fans will] be using for that release,” Nash adds. “We know that going into it. We are prepared. We have our armor on.” She begins to laugh. “I get so mad, Mark keeps me off the internet!”

While Thrower says he personally hasn’t received any blowback from the Coil faithful (“I don’t fret about these things and my inbox has been lovely”), at times the labels have had their motives challenged by ardent fans with all the subtlety of a colonoscopy. Skillicorn admits it does get tiresome, but appreciates anybody caring in today’s seemingly temporary, swipe-left culture. “That’s what we’re getting into. But that’s what a fan is: They obsess about who they love. And they’re very protective. We have received very positive feedback from the fans at this point who are very excited and very happy we’re doing this.”

The 30th anniversary reissue of Love’s Secret Domain is more than a comprehensive overview of a fascinating album. It has been impeccably restored and bolstered by Bonati’s exacting mastering skills and his finely tuned sense of the appropriate. Wax Trax’s presentation of the set is similarly respectful, creating an artifact that is sonically/visually arresting while maintaining the covenant of fan service. Revisiting LSD three decades later reveals the cartography of paths artists have (un) knowingly followed as well as places not fully explored. Rushton, Christopherson, Thrower and Hyde navigated both sides of the psychic-razor highwire like bloody-footed Wallendas, pushing their consciousness, bodies and personal losses to create it.

In an era where social media allows artists to control the narrative in the name of “transparency” (furtive or otherwise), Rushton and Christopherson are making surreptitious mystery cool again. Even in death.

“If you didn’t know anything about Coil, you went into the community and started listening to people [who were fans],” Bonati offers. “The Coil community is very obsessed with the mystery of Coil. There are a lot of interesting things, unsolved details and stuff about the band that make me really nostalgic for when there was a lot more mystery involved in music. You can live in the mystery of Coil if you want. Bands reveal everything on social media accounts. It’s part of a marketing strategy now: You have your record, but maybe you also endorse products and you have a YouTube channel and there’s tons of footage of you in the studio. We don’t have that stuff with Coil. And it kind of heightens the experience or enjoyment being a fan of this band. I think they’re one of those bands that encapsulate that feeling.”

Three decades after the inception of Love’s Secret Domain, maybe the rest of the world has finally caught up with Coil. The solemn fact that neither Rushton or Christopherson are here to reflect on their intentions, discuss the album’s resonant wattage or dismiss its purported conventional wisdom only makes the proceedings even more alluring, fascinating and melancholy. (Rushton, 42, died from injuries received in a second-story fall in his London home on November 13, 2004. Christopherson, 55, passed away in his sleep in his new home in Bangkok, Thailand, November 25, 2010.) Thrower has some hints as to what kind of sonic/psychic marrow listeners old and new should extract from this ambitious reissue.

“Mind-body derangement! Passion and reflection. An intense, obsessional experience beyond the everyday. We made the album with an intense concentration on sonic detail, designed for deep listening, not casual skimming. Danny Hyde did a fantastic job on the production, and the visiting presences of Annie, Marc, Charles, Billy [McGee, orchestrator] and [didgeridoo player] Cyrung make it all feel incredibly alive and potent. To me, there’s a vast world imprinted into these sounds and spaces. I hope it can be accessed by dedicated listeners who really immerse themselves and voyage inside it.”

But the last word on Coil belongs to Hampshire. It’s an anecdote about him having to arrange for Christopherson’s Thai funeral ceremony and cremation. The story is both a tribute to his close friend and an aside to remind extreme fans to focus on things that really matter and not be distracted away from the true message.

Hampshire and a friend went to the Bangkok Police morgue to retrieve Christopherson’s body in order to prepare it for funeral services. Officials wouldn’t release the body until Hampshire secured documentation from the British embassy. After securing the paperwork, the officials allowed him to take his late friend’s body to a temple.

“So they said, ‘OK, now you may take his body to a temple. Are you going to take him?’” Hampshire recalls. “I said we didn’t know and the official said, ‘OK, we have a service.’ We’re thinking this will be like a funeral service. We handed the money over, and then this guy just walked out in this scruffy boilersuit who I thought was an electrician or something. The official said, ‘OK, he’s going to take it and get it all done.’

“So this guy, he was just so Sleaze’s type. He would have just adored this guy. He was like this 20-something-year-old, gorgeous-looking Thai lad in this boilersuit. ‘Oh my God, Sleazy would completely love that.’ And he was like, ‘OK, come with me.’ We got in a van and they put Sleaze’s body wrapped in shrouds and things and put it in the back of this van. Then we’re squeezed in the back and in the front is the driver and this boy. As we’re driving to the temple that we’d arranged for the five-day funeral rite, this gorgeous Thai lad winds down the window, reaches down into a bag of Thai bahts—that’s like a cent, a penny, basically—and he starts to throw them out of the window randomly.

“So we said to him, ‘What are you doing?’ And he said, ‘It’s for the spirits, so that they don’t follow us. We will distract them with money.’ I just felt at that moment, this gorgeous young lad throwing money out of the van window for the spirits: It was almost like Sleazy directed that. It really was the perfect moment for him. And that’s when I felt like he’s with us, sorting shit out.”