Researchers have identified a new species of great ape that lived around 11 million years ago, finding that it had a somewhat unusual living situation.

Named Buronius manfredschmidi, the extinct species is estimated to have weighed about 22 pounds, making it the smallest known great ape, according to a study published in the online journal PLOS One.

The great apes, or hominids, are a family of primates that contains modern humans and our closest living relatives—bonobos, chimpanzees, gorillas and orangutans—as well as a number of extinct species.

In the study, a team led by Madelaine Böhme of Eberhard Karls University in Tübingen, Germany, and David Begun of the University of Toronto describe the fossils of the previously unknown species.

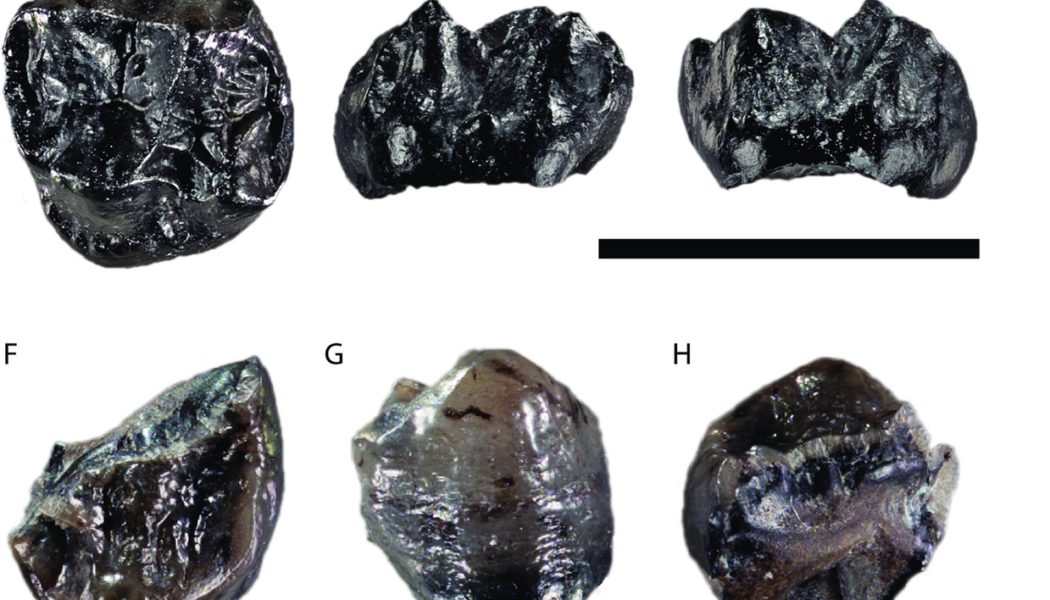

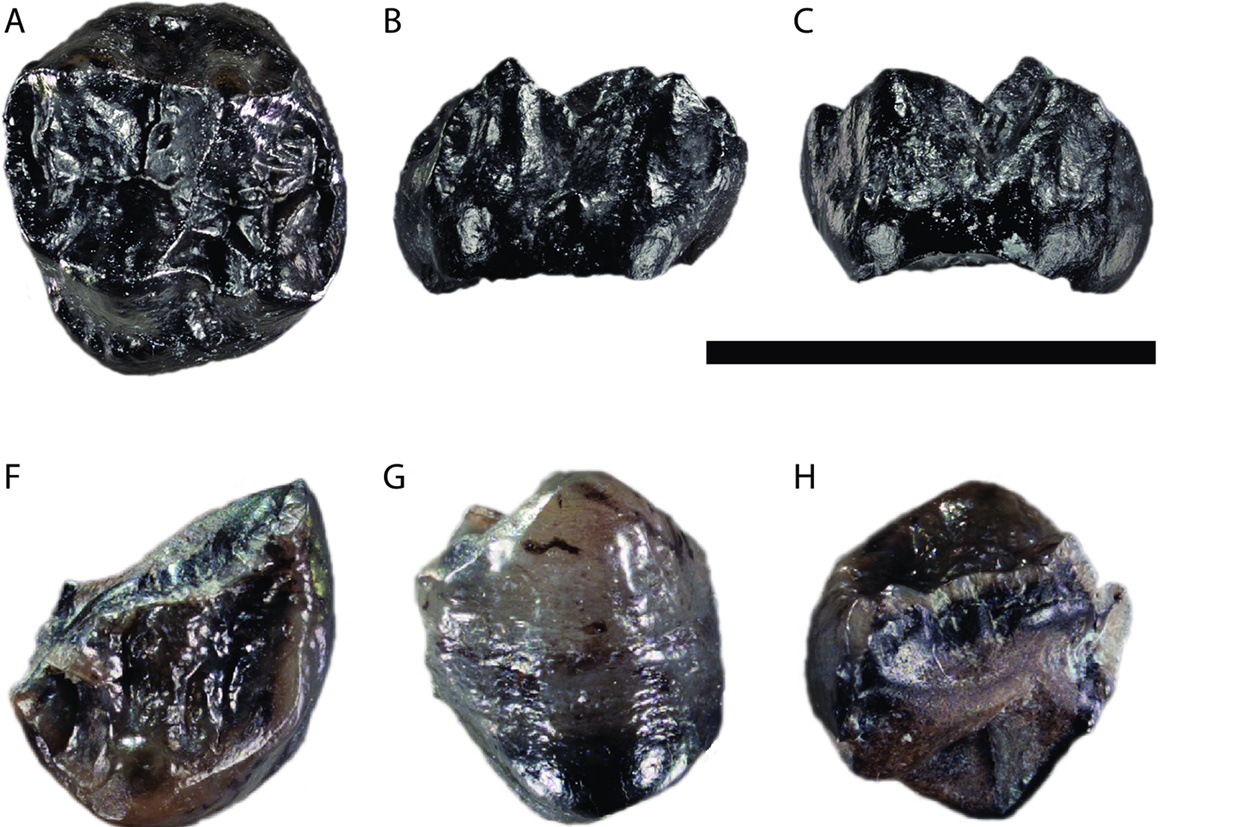

Pictured are fossils of a newly described great ape species, Buronius manfredschmidi. Researchers estimate that this species had a body weight of around 22 pounds, making it the smallest known great ape.

Böhme et al., PLOS ONE 2024), CC-BY 4.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/

The remains that the description of B. manfredschmidi is based upon originated in the Hammerschmiede fossil site in Bavaria, a state in southeastern Germany. These remains consist of two partial teeth and one patella, or kneecap.

The Hammerschmiede site is best known for being the location where the remains of another extinct great ape, Danuvius guggenmosi, were first discovered. This ape lived around 11.6 million years ago during the Miocene Epoch, which lasted from roughly 23 million to 5.3 million years ago.

The fossils of B. manfredschmidi come from the same geological layer as Danuvius, indicating that the two great apes lived around the same time. This is significant because previously no fossil sites dated to the Miocene in Europe had been found to contain more than one species of great ape.

In the study, the researchers analyzed the B. manfredschmidi remains, shedding light on its behavior. The bones indicate that this ape was a skillful climber whose diet primarily consisted of soft foods such as leaves.

The authors also estimated the body weight of the animal based on the size of the available fossils.

The patella of B. manfredschmidi appears to differ in its characteristics from that of Danuvius—and indeed all other known apes. In addition, the relative enamel thickness in the teeth of B. manfredschmidi is thin, in contrast to that of Danuvius, whose enamel is twice as thick.

These differing traits suggest that B. manfredschmidi had a distinct lifestyle, compared with Danuvius, which was larger in size and consumed tougher foods.

The study authors propose that the two apes were able to coexist in the same habitat because their differing lifestyles meant they were not competing for resources. This kind of coexistence bears similarities to modern gibbons and orangutans, which share the same habitats in the Southeast Asian islands of Borneo and Sumatra.

Do you have an animal or nature story to share with Newsweek? Do you have a question about paleontology? Let us know via science@newsweek.com.

Borneo, Sabah, Malaysia, South-East Asia, Asia. The newly discovered ape’s coexistence bears similarities to modern gibbons and orangutans, which share the same habitats in the Southeast Asian islands of Borneo and Sumatra.

Uncommon Knowledge

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.

Newsweek is committed to challenging conventional wisdom and finding connections in the search for common ground.