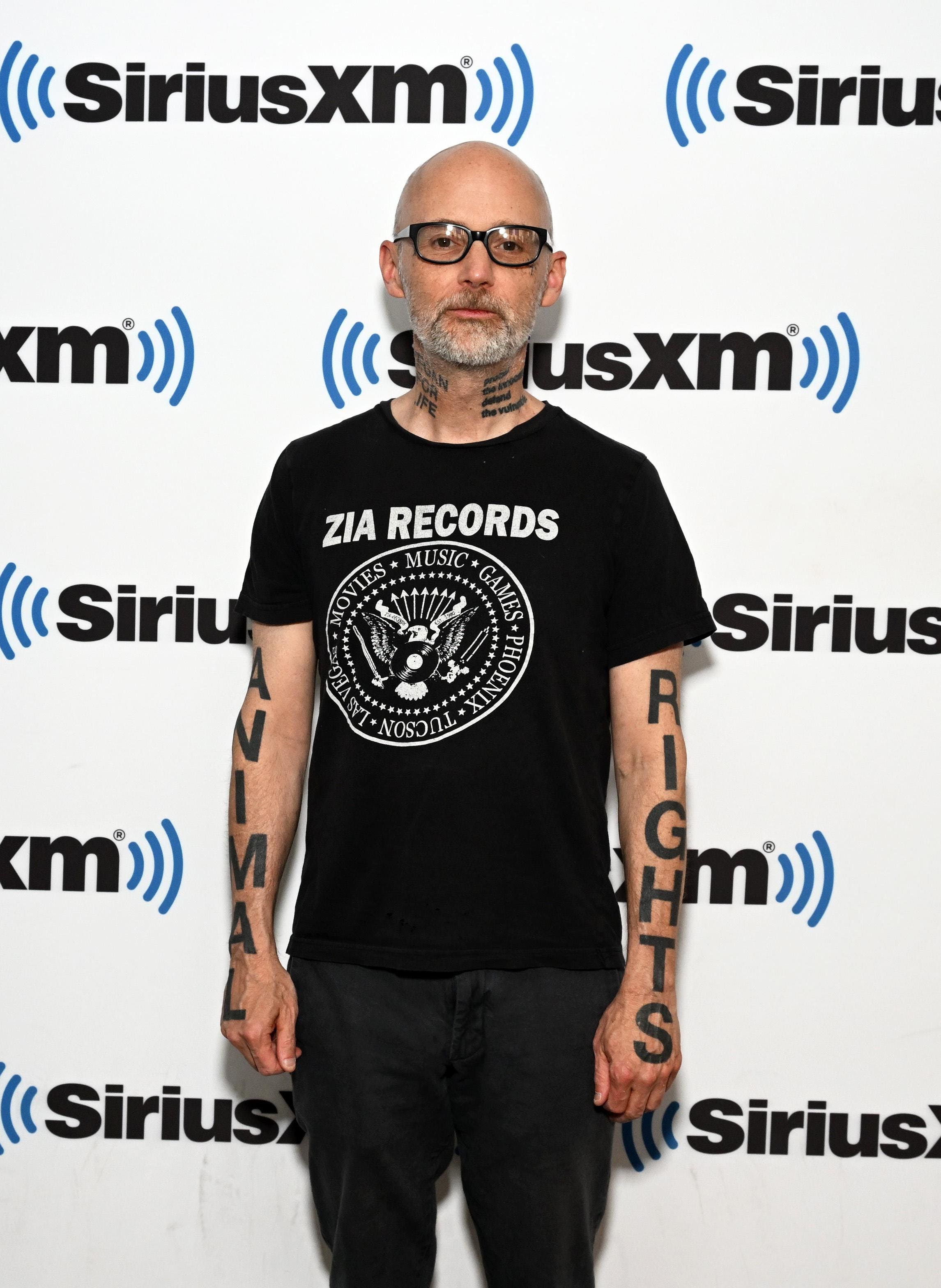

Moby is one of my favorite interviews in all of music. Since our first conversation back in the ’90s, every talk has been a thoughtful and highly cerebral discourse on a vast array of topics, from music and his friendship David Bowie to philosophy and religion.

Then, you throw in the impressive intellectual curiosity of singer/songwriter Sage Bava (like Moby a devout vegan, so they bonded immediately), which adds a freshness to the ongoing nearly 30-year conversation Moby and I have had, and you have an interview for the ages.

The impetus for Bava and I jumping on a Zoom with Moby is his new album, Resound NYC, which finds him reinterpreting some of his most iconic songs — like “Extreme Ways,” “South Side” and the gorgeous ambient classics “When It’s Cold I’d Like To Die” — with artists ranging from Gregory Porter and Danielle and Elijah Ponder to Nicole Scherzinger and Damien Jurado.

We chatted with Moby about the new album, how he chooses which songs to revisit, why AI can’t replace human emotion, at least for now, veganism and much more.

Steve Baltin: Let’s jump onto the record. How do these songs change when you bring new interpreters onto them and come back at them with a fresh perspective of, again, now looking at it from the standpoint of a 57-year-old, which is very different than when you write a song when you’re in your 20s.

Moby: Apart from the fact that just simply and possibly selfishly, I love going back and, maybe it’s even narcissism on my part, revisiting older songs and reworking them. It’s such a delightful process, it’s so much fun and so creatively satisfying, but especially songs that were written, recorded 20 some odd years ago. And this can sound very pretentious and I apologize, but there’s the Proustian component of revisiting the past. The most viable aspects of nostalgia or revisiting the past of getting older is having a expanded basis of comparison, having a broader perspective. And there is one aspect to that which is quite depressing, [laughter] apart from just getting older and being old. But in looking back at these songs, there’s this recurring motif of being confronted with cultural optimism. I don’t want to be a super cranky old guy, but if you remember like the mid ’90s, the late ’90s, even the early 2000s, there was so much optimism, especially in the ’90s. Bill Clinton was president, our climate change book writing friend Al Gore was vice president. The internet was going to be this force for communication and democracy. Russia was talking about joining the European Community. China was enacting democratic reforms. There was no such thing as pandemics. War was largely disappearing. The world was so optimistic. And sorry for being such a bummer. But like that optimism for most people seems to have largely disappeared. And it’s really kind of like a bit depressing being nostalgic for that period of multifaceted optimism.

Baltin: I feel like there’s still reason to be optimistic today.

Moby: Oh, yeah, that’s the thing. A lot of spiritual practices do stress the importance of not letting loud negative ideas crowd out quieter, optimistic, hopeful ideas. And I can be very guilty of letting the negative overwhelm the positive, and you’re right, there are a lot of really very positive things. And I was talking about this with Cory Booker a while ago, I’m sorry for the name dropping, but Cory’s at present my only friend in the Senate. We were talking about how one of the only things humans are better at than causing problems is fixing problems. You look at human history and like boy, humans are so well-accomplished at creating problems, but then they’re really good at also fixing those same problems. So the hope is all of the problems that we’re facing that humans have created somehow maybe once people are confronted with the consequences of these problems, maybe we’ll figure out a way to actually address them and solve them and have some sort of like utopian Star Trek future as opposed to like a dystopian Mad Max future.

Sage Bava: I’d love to ask about that future and where you think music and AI will intertwine, if you’re excited about it or if you’re terrified about it.

Moby: It’s funny, I still don’t fully know how AI is defined. And what I mean by that is like, I’m sure as a fellow musician, you understand we’ve been using intelligent predictive algorithms and software for a very long time. Like when you quantize a MIDI part that’s sort of AI, if I put some light Melodyne tuning on background vocals, isn’t that AI, ’cause you’re sort of asking the tech to interpret? So I’m still trying to figure out where does old-fashioned predictive interpretive algorithm tech end, and where does AI start? And I’m sure there’s a pretty simple answer that I’m just not smart enough to figure out. But given especially, as you probably both know, there was a song released a couple of days ago that was a new Drake and The Weekend song turns out it was a song 100 percent created by AI, but it was indistinguishable from a new Drake-Weekend song. Personally my thought is AI is going to be really good at creating generic auto-tuned pop music. Because up until recently, so many of the pop producers like their goal has been to create generic auto-tuned performances, their goal has been to take people’s vocals and do everything in their power to make the vocals sound technically perfect, and that’s what AI is good at, so if I was a pop producer, I’d be scared. And maybe this is just because I’m an old guy, but I do feel like what AI will never do, at least not for a very long time, is create the authentic vulnerability of a Leonard Cohen or on my last record with Deutsche Grammophon, I had to do that with Mark Lanegan and Kris Kristofferson and I don’t think AI can do that to create vulnerability, to create that sort of the rough expression of the human condition. So if I was a generic pop producer, I’d be scared, but if you’re Rick Rubin looking to make a record with Kris Kristofferson I wouldn’t be too worried.

Baltin: Your mind opens up so much more as you get older. So a lot of this stuff, do you feel like you could have embraced it when you were younger?

Moby: Oh, absolutely. I forget where I was reading this. I’ve never had a child, and I’ve certainly never been a woman breastfeeding a child, but apparently the process of weaning a child off of breast milk is very upsetting, and the child screams because the baby has decided breast milk is the way to be happy, is the way to feel a connection, is the way to stay alive. And trying to separate the baby from the breast milk, I guess it’s a very difficult process for mothers and in a very expanded way, makes me think of what you just said, how painful the process is of being disabused of all of the ways we thought we were right. I really thought when I was growing up the answer to happiness was some facet of cultural materialism. I was like, “Okay, if I get enough validation as a musician, if I have enough money to pay the rent, if I had the right relationship, if I live in the right city, if I read the right book and see the right movies and go to the right parties and have the right friends, then everything’s gonna be fine.” And I don’t want to anthropomorphize the universe, but the universe kind of said “No, it’s not any of those things.” And so you could almost say to your point, as we get older, possibility and potential are taken away from us in order to show us how much more potential there actually is. It’s kind of like the platonic idea of leaving the cave, the universe doesn’t want us to stay in the cave, the universe doesn’t want us to stay ignorant, but leaving behind the comfort of ignorance is excruciating. And you don’t want to go through it, but it’s the only way to not be trapped by that weird materialism of, just give me the right house and the right relationship and the right validation and everything will be fine, because as we know, that’s never the case.

Baltin: Like you I’ve done everything, I’ve partied at Prince’s house, seen every band in my lifetime, including the Led Zeppelin reunion show, but I found it’s the little moments. So I actually find it the opposite, and I didn’t find it excruciating at all. I found it to be the most rewarding thing to realize that.

Moby: Ultimately, I agree with you, it is incredibly rewarding, but how excruciating it is like when it stops working, ’cause I really believe, to my great shame that fame was going to fix things. Thatstanding on stage and being on tour and all the stuff that comes along with that, I just thought that was going to fix things. And so when I say materialism is both, I’d say conventional materialism, but also just the idea of external things, external validation, external even relationships. What have you. I found it to be very painful realizing that ultimately, there’s nothing wrong with fame, there’s nothing wrong with accolades, there’s nothing wrong with red carpet events and parties, as long as you don’t expect them to fit or fix spiritual problems, and my mistake was, I absolutely did. I thought they were going to protect me from the worst parts of the human condition. When you’re a musician, like when I was growing up, I was like, “Oh, if I’m ever standing on stage in front of an audience and they like my music, I will have arrived.” And you never think that these things are possible the same way the majority of people on the planet probably think, “Oh, if I win the lottery, everything’s gonna be fine. Oh, if only I had a movie star boyfriend or girlfriend, everything’s gonna be fine.” And for the vast majority of people, they won’t get there, and so they can always hold on to that idea that if I had the right sort of existential portfolio, I would fix this. But the weird thing about becoming a public figure musician is you get everything and you get more than you wanted, and I’m not complaining, or looking for sympathy, but you’re given more than you ever thought you’d ever have, and the happiness doesn’t follow. If anything, you’re left with what you’re describing, as that sort of that fear and that frustration of like, “Oh no, I spent my whole life working to get to this place, and now I’m in this place. And what’s next? ‘Cause this didn’t work.” And for me, it had to be bottoming out as an alcoholic and drug addict and learning to find joy in incredibly simple thing, animals, nature, science, music for the sake of music and not necessarily the commercial aspects of it. That’s what I mean about the pain being broken from those beliefs and assumptions, ’cause you then have to replace them with something else, and that can be super challenging.

Bava: Something I was thinking a lot about yesterday is this idea of coming back to self, and one of my favorite quotes is “The privilege of a lifetime is to become who you truly are.” Carl Jung. And I was reading an interview you had, and I loved what you said about our connection to animals and how animals are the Divine, and we have just severed that, and any time we abuse that, it’s just exclaiming our separation from it.

Moby: Yeah, I couldn’t agree more. I think you’re absolutely right, and the Jungian aspect is really interesting. So in the beginning of the pandemic, I went back and tried to re-read a bunch of the philosophy that I read in college. Everybody from Aldous Huxley to Jung to [Baruch] Spinoza, etcetera, just going back and reacquainting myself with a lot of the stuff that I’d read a long time ago. And the most interesting aspect of everything I read, ’cause a lot of it, when you put it in context, doesn’t really hold up too well, like the phenomenologist, I really appreciated. But it was the Jungian idea of the shadow self, and traditionally, I feel like most people interpret it to be like the Marilyn Manson self, the Trent Reznor self. And I’m not criticizing either one of them, but if people think of the shadow self as being dark and scary and with bitterness and vicious, and I had this go to realization that for me, the shadow self is uncomfortable, it’s the awkward self, it’s the self that says the wrong thing. That was just like an awkward 13-year-old adolescent and continues to be that. Like the shadow self is the part that we don’t want to look at, it’s not the violent part, it’s not the sexy part, it’s the uncomfortable part. And I really think to your point, like feeling that, like reconnecting with that awkward self, the vulnerable self, integrating the self with the self, and that means accepting that we get older, accepting that we don’t always look great, accepting that we are awkward human beings. But I personally believe that until humans figure this out, we’re going to be just lost in the wilderness, and eventually we might even end up destroying ourselves as a species because we’re unwilling to heal this rift, to connect with that deeper idea of we are natural beings, we shouldn’t aspire towards algorithm fuel, perfection, we should aspire towards the best expression of the human condition.

Baltin: What were you looking for in the people you worked with on this, and what were you looking for in the songs that you revisited?

Moby: Well, part of it is the Neil Young criteria for choosing greatest hits. I remember reading an interview years ago where Neil Young had made a greatest hits album and the journalist was like, “Oh, how did you choose the songs?” And he said, “Oh, these are the songs people wanted to hear.” And I thought that was so honest and simple and delightful. So with this record, and the last one, half of the songs are songs that people have proven or shown me over the years that they want to hear, and I love them as well. Like “Extreme Ways,” you go on Spotify and it’s like, “These are the ones that people have said they want to hear, so I’m thrilled to go back and revisit them.” But it also gives me a chance to sneak in a bunch of weird obscure other songs that people might not have heard. I did that with the first record as well, and the version of the song, “The Lonely Night,” that I did with Mark Lanegan and Kris Kristofferson, that’s the whole reason that album exists. The rest of the album, I think is good. So with this album, I love the big loud songs in the beginning of the record, but as you get towards the end of the record, some of the quieter songs like Lady Blackbird doing “Walk With Me” and Danielle Ponder and her 76-year-old dad doing the song “Run On” or the song “Last Night,” those are the ones that I’m hoping at least some people might listen to the album to the end to discover these otherwise really insecure songs.

Baltin: What do you hope people take from this record when they hear it?

Moby: Honestly, the same thing I took from it when I was making it, which is the idea of music as a refuge. I find now that I don’t tour and I don’t pay attention to record sales, to me, the function of music is emotional refuge. Sometimes that can be The Clash, and sometimes it can be Nick Drake, sometimes it can be Billie Holiday, and sometimes it could be Pantera, for everybody, it’s different. But it’s that idea of music as a world that you can step into and simply feel better than you did before you stepped into that musical world.