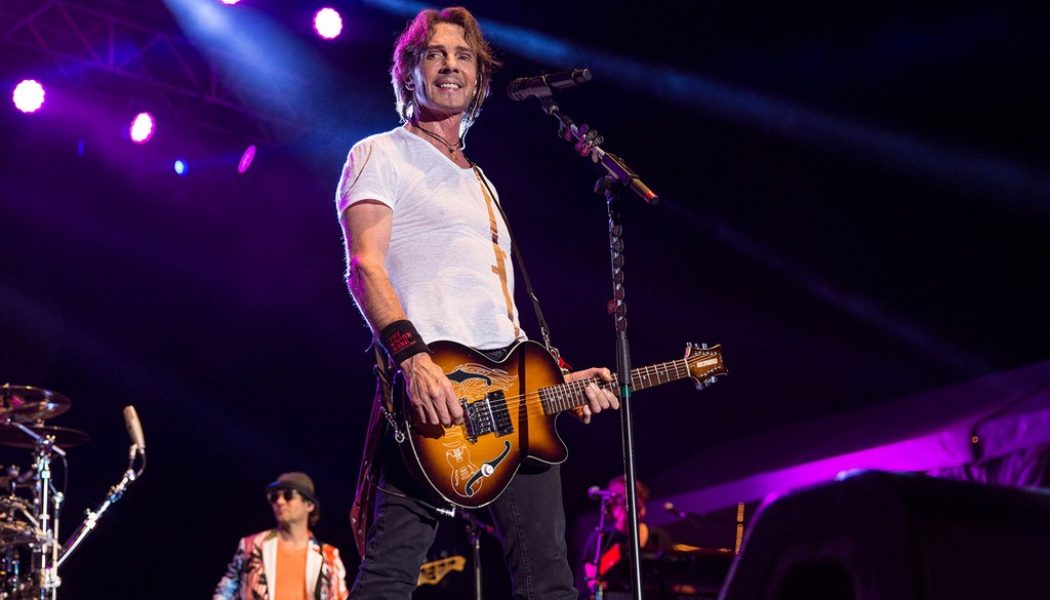

Though the pandemic has pushed back a 40th anniversary tour, Springfield plans to play the album from start to finish when he’s able to return to the road and has been relearning the tracks. “When I first started, they were the only songs that I had so I played everything,” he says. “But I haven’t played the whole record since ’81.”

Additionally, Springfield hopes to reissue the album, which he produced with Bill Drescher and Keith Olsen, to include demos of the songs that didn’t make it onto the finished set. Below, a genial Springfield dives deep into the making of the album with Billboard, recalling why he didn’t want his photo on the famous album cover, and how he juggled budding stardom with appearing on soap opera General Hospital, where he played the libidinous Dr. Noah Drake.

What was your mindset when you were recording the album?

I wrote the songs because I had given up on ever getting another record deal, and L.A. clubs were hot at the time. So I thought I’d write a bunch of short pop songs with catchy hooks that I could play with a three-piece band, and go do the L.A. club scene. I was surprised when I got the deal, [which] didn’t really seem to be in the cards for me.

You recorded it at the now legendary Sound City, which your then-manager, Joe Gottfried, owned. What was that like?

We’d get called at two o’clock in the morning saying, “Tom Petty just left. You got the studio till six or seven in the morning.” So Bill Drescher and I would run down and record and mix. Then when the paying client came in, we’d get kicked out. It basically was one of the cheapest albums I’ve ever made. I had it all demoed and knew all the parts and was ready to go.

Did you have any interaction with Tom?

No, because we were there when everybody had left, not even a cleaning crew. I saw him not long before he passed away. I did a movie called Ricki and the Flash with Meryl Streep, and we’d done a version of “American Girl.” I was at the pharmacy, and this guy walked in with a cowboy hat and dark glasses and he leaned over and said something to me. I said, “God, I’m hard of hearing. Sorry, what’d you say?” He said, “I’m Tom Petty. I just wanted to say I really like what you did with ‘American Girl’ in the movie.”

Courtesy Photo

Rick Springfield, ‘Working Class Dog’

Working Class Dog chronicles a guy in his late 20s focused on love, lust and betrayal. In some ways it’s like reading diary entries. Looking back, did it capture what you were going through in your late 20s?

It was absolutely that. I would say things — like one of my favorite phrases was “Dammit, I just know it,” and it ended up in “Jessie’s Girl.” It was a very, very, very personal record. I felt free writing it, which is why one of the reasons it worked. Joe was a fabulous human being. He said, “I’m going to put you on salary in the studio for three months and so you can just be free to write,” because I always had money problems. It was very much what was going on in my head. A lot of lust, a lot of lust. That’s obvious, right?

When you listen to the whole album in one sitting, it’s like a freight train of lust coming at you.

And not so much betrayal, but the fear of betrayal. I remember at 16 years old, I finally got this girl that I was after in high school — and I split with her because I was afraid she’d drop me first. You have one love in high school, and she was it for me, but that’s how insecure I’ve always been.

Had you finished recording it before you started on General Hospital?

Yeah and [the label] sat on it. RCA didn’t know what to do with it because disco and ballads were coughing up blood, but they were still alive on the radio. So they sat on this guitar-based pop record. They kept delaying the release and delaying release and I’d go, “Oh, here we go again.”

Then this part for General Hospital came up, and I only took it because I needed the money. I didn’t think it was any kind of career move… I thought, “Nobody watches these shows except blue-haired old ladies ironing.” But it just happened to become the popular TV show among college kids that summer. It was serendipitous.

How long did it take to record the album?

Two to three months because it was so spaced out. The two tracks that I did with Keith Olsen, “Jessie’s Girl” and “I’ve Done Everything,” were recorded properly. We’d go in at 11 o’clock in the morning and do a whole session. Keith Olsen was a big producer at that point. He’d done Fleetwood Mac and Foreigner and Pat Benatar. So he was going to do me a favor by doing these two tracks with an unknown.

Did you know “Jessie’s Girl” was a hit when you wrote it?

No. I was actually disappointed because I played Keith all my demos — I had about 15 songs — and he picked “Jessie’s Girl,” and I went, “Aww, why’d he pick that one?” Because I thought there were better songs on the album. But Keith had great ears and I trusted him, and he was right.

Where were you were when you heard it hit No. 1?

I was in the rehearsal room at Sound City. My manager Joe and [co-Sound City owner] Tom Skeeter came in with a super, super-cheap bottle of champagne saying, “We just hit No. 1.” Champagne never tasted so good. I was thinking, “Now I have a shot.”

“Jessie’s Girl” went to No. 1 the week that MTV launched. How much did MTV have to do with the success of the record — or did their support come later?

When I did the videos for “Jessie’s Girl” and for “I’ve Done Everything For You,” RCA gave us like 1,500 bucks and said, “Go make two videos.” I remember thinking, “Why am I even doing this?” I didn’t even know about MTV. I wrote up a quick storyboard for a “Jessie’s Girl” video, and we shot with a three-[person] crew.

We couldn’t get permission. The alleyway shot at the opening is the back of the old Guitar Center on Sunset Boulevard. We went there about 3:00 in the morning. We cranked up the song and did a couple of shots, and then heard the police were coming, so we threw our stuff in a van and took off. It has an ‘80s cheese to it, but I think my dog at the end was the redeeming factor.

That’s the same dog that appears on the cover of Working Class Dog. Though you appear in a small snapshot, why did you decide to put him on the cover instead you?

I went to RCA and said, “I want to put my dog on the cover.” They thought I was joking and said, “No, you’re on a TV show, of course you’re going to go on the cover.” I was kind of adamant that it wasn’t me on the cover. I didn’t want another stupid pretty boy shot that would just turn a bunch of people off. I wanted something that everybody could go, “That’s cool.”

I loved my dog, as I love all my dogs. And so I measured his neck, and it was 18 inches, and I figured, “That’s a pretty damn big neck.” So I went to a Big & Tall store and said I wanted a white, button-down shirt with 18-inch neck. [The salesman] said, “What sleeve length do you want?” I said, “It’s for my dog, it doesn’t matter.”

General Hospital boosted your exposure, but did you worry that some people didn’t take you seriously as a musician because of the show?

It was definitely a yin-yang situation. When “Jessie’s Girl” finally hit, it was played on what they called AOR [album-oriented rock] stations. It was the heavy station where they played legit bands and all that kind of thing. And they played it a lot, because there wasn’t a lot of guitar music around. It was one of the few big hits that actually had a guitar that prominent in it. But as soon as they found out I was on General Hospital, they started dropping the song from the playlist, because General Hospital geek and rock guy didn’t really go together.

So there was a definite downside. A lot of people thought, “Oh, here’s this soap geek that someone managed to have sing in tune for three minutes, and that’s the last we’ll hear of him.” I have fought that battle for a long time.

How did you balance taping a soap opera, promoting the album and going on the road all at once?

I’d finish a show on Friday and catch a plane somewhere to do a gig Friday night, then do a gig Saturday, then do a gig Sunday, get up at like three o’clock in the morning and catch a plane back to L.A. Instead of asking for more money when the show became really popular, I asked for more time off. I was really only on [General Hospital] for 18 months. When my renewal came up, I said, “No, I’m going to hit the road. That’s my first love.”

“I’ve Done Everything For You” was written by Sammy Hagar. How did that one come to you?

[Pat Benatar’s husband and guitarist] Neil Geraldo brought that to Keith for Pat, and I think Pat didn’t think it was right for her. So when Keith was looking for a second song — which I was already pissed that he hadn’t picked one of my songs for the second song he was going to do; I think he was just trying give himself some insurance in case I wasn’t the writer that he maybe thought I was — he brought this Sammy Hagar song. I thought it was a pretty good song. Neil came up with the opening riff. It was basically his arrangement of the song and I just sang it.

Sammy [and I] maintained contact. We’ve just hooked up with his Beach Bar Rum, and I’ve joined to help promote it. We’re going to go out and tour and promote it too. We were talking about that before the whole lockdown came, but we will get to that.

Did you resent the song, or did you grow to like it?

Obviously once it became a hit, I was going, “It’s an awesome song.” [Laughs.] They released it first [before “Jessie’s Girl”] and it didn’t do anything, but as a second single, it was definitely the right song. It has power, and a good message.

The third single was “Love Is Alright Tonite.” The album takes its name from one of the song’s lyrics, which also include your telling your date’s dad that she’s “going to be feeling it tonight.”

Yeah. That was just me trying to be a punk. [Laughs.] It was one of the first songs I wrote for Working Class Dog. I thought it was a good template for the whole album — short, hooky, guitar-driven. I was trying to make good pop songs, but with something that would make you go ‘huh?’ at some point.

What part of the sudden stardom, after struggling for so long, was the hardest part for you?

I think trusting people. That’s why so many musicians get screwed. They think, “Oh, I don’t have a business mind, I’m an artist — so I’ll leave it to the business people who know what they’re doing.” But 80% of them don’t know jack s–t. You probably know more about it and care more about it than they do, because it’s your lifeblood and your music and your money. So that was difficult… not really getting screwed, but understanding that they don’t really give a s–t about me. It’s just about their career and who they have on their roster. The business side of it was a learning process for me.

AOR stations may have dropped you, but you had the final victory when you won the Grammy for best male rock vocal performance in 1982. Did you feel validated?

No. I never put platinum records up on my wall or anything like that. I always considered once it’s done, it’s on its own. I put one up — the first gold record I got for Working Class Dog, mainly because my dog was on the cover and I was proud of of the cover. In retrospect, it’s nice to look back and go, “Okay, that’s kind of a signpost.” But it wasn’t like, “Oh. My. God., I’ve made it.” It was, “That’s cool. Let’s just get onto the next record and let’s get onto the next concert.”