This article originally appeared in the November 1993 issue of SPIN.

A sea of upraised middle fingers are pumping rhythmically into the enervating Southern California heat and smog. “Fuck you, I won’t do what you tell me,” the audience shouts over and over, a few mindlessly mimicking the mantra, but most passionately chanting singer Zack de la Rocha’s invective rant from “Killing in the Name.” In the massive mosh pit objects sail through the air every few seconds, as Doc Marten-clad trendies are passed hand-over-hand above the tattoos and sunburned shoulders of the Lollapalooza nation.

Onstage, Rage Against the Machine‘s insistent, hard-core rock-rap amalgamation is nearly overmatched by its rad political clamor, spewed forth both in the songs and in the longish pauses between them. During this show, however, de la Rocha surprises even his bandmates by lashing out against a Los Angeles radio station, alternative giant KROQ-FM. The station has been uncommonly supportive of the LA-based band, but has also been playing unauthorized, edited versions of Rage’s anti-gang-violence manifestos, “Bullet in the Head” and “Killing in the Name.” Versions siphoned off such offensive words as “motherfucker.”

Within days, all Rage songs are pulled from said station. “I was very disappointed that the band would attack the station that supported them in a way few other stations have,” said KROQ program director Kevin Weatherly, noting that FCC regulations preclude on-air profanity. ‘The thing reeks of hypocrisy. We never got one call (before de la Rocha spoke out) requesting us to pull the song off the air.”

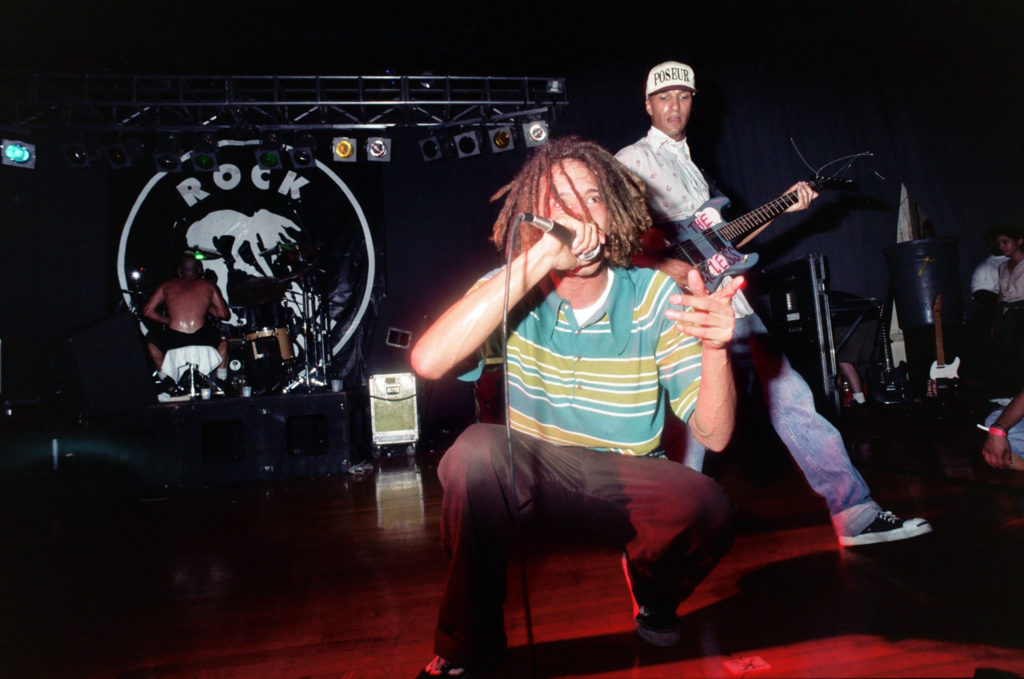

Yet an hour after Rage’s Lolla performance, which, typically, proved both inciteful and insightful– and moments after being interviewed on the air by the very radio station his singer just crucified—guitarist Tom Morello is surprisingly calm. As we perch on the concrete embankment above the semi-stagnant water of the Santa Fe dam, Morello, shirtless and in a baseball hat emblazoned POSEUR minces no words. “Do you have an agenda?” he says forthrightly, “Because if you don’t, I do ”

Rounded out by bassist Timmy C. and drummer Brad Wilk (formerly of Eddie Vedder, pre-Pearl Jam outfit and buzz band Greta), the two-year-old band had its first major-label offer following its second gig. “Individually, we’ve paid our musical dues, but as a band, we never did,” acknowledges Morello, late of Geffen Records act Lock-Up. “It’s almost obscene. A bunch of guys in suits just salivating, offering these exorbitant amounts of money for punk-rock songs. Whatever. This business of music,” he laughs dismissively.

After an endless round of power-schmooze meetings with every label in town, the sought-after band inked with Epic, a coup for A&R wunderkind Michael Goldstone, who signed Mother Love Bone at PolyGram and Pearl Jam at Epic. After rave reviews but slow sales, Lollapalooza kick-started the career of enfant terrible de la Rocha and his band of merry muckrakers. By September ‘93, nearly a year after its release, Rage Against the Machine was lodged at No. 70 on the Billboard album charts and had sold 400,000 copies, without significant MTV or radio exposure. And with a political agenda far to the left of Michael Stipe’s.

“We have a realization that from top to bottom the system is corrupt,” explains Morello, adding that Rage’s intent is to “create a climate where things can happen. It’s all about empowerment.” While there are many messages in the music—the bankruptcy of education and media in “Take the Power Back,” the anti-gang warfare of “Bullet in the Head”—two songs sketch out the band’s non-specific call to arms. In “Fistful of Steel,” de la Rocha sings- “Something about the silence makes me sick…I’m a bastard son / With the visions of the move / Vocals not to soothe / But to ignite and put in flight / My sense of militance.” And on “Wake Up”: “I’m mad / Still knee-deep in the system’s shit / I’ll give ya a dose / But it’ll never come close / To the rage built up inside of me / Fist in the air / In the land of Hypocrisy.”

Is it merely sound and fury, with an eye on the profit prize? Does Rage walk it like it sings It? Well, yes and no. To the charges of hypocrisy leveled at the quartet by KROQ, the band acknowledges de la Rocha may have spoken out too quickly against the station. “I didn’t think it was the right thing to do,” Wilk admits, “because they’d been so supportive. We could have called them up months ago and said, ‘Thanks, but please don’t cut our record.’ But on the other hand, it was what Zack felt at the moment, so I can’t blame him.”

And while Rage owes an immeasurable debt to Lollapalooza for jump-starting its moribund debut disc, that gratitude failed to prevent de la Rocha’s daily tirades against the festival’s greed, including public pronouncements taking the Lollapalooza organization to task for its $23 T-shirt prices (Rage did not sell its own shirts at any stops on the tour, though they still received a percentage of profits from the Lollapalooza event shirts).

Then, on the Philadelphia stop of Lollapalooza, Rage unleashed its most highly publicized display of sloganeering. Morello explains. ”The facts of the case were this: We stood on the stage for about 14 minutes, naked, just letting the guitars and bass feedback, with the letters P.M.R.C. written in big, black letters, one on each band member’s chest with black electrical tape over our mouths. The point, which I thought was obvious,” notes Morello, “was probably lost on some people. And it was, ‘If you don’t confront censorship, then the music of confrontational artists is going to be silenced.’ People at the show were wildly enthusiastic for the first five minutes, then they realized it wasn’t going to be a feel-good protest then the second five minutes, they were silent waiting for the rock to begin, then the last five minutes they were actively hostile, very uncomfortable, and upset” he says, pleased. “And that was the whole point, what we were trying to get to, to let them know you will not be able to hear the music you want to hear unless you do something about it”

Mike Muir, whose bands Suicidal Tendencies and Infectious Grooves recently opened for Rage, openly questions the band’s motivations. ‘There’s a fine line between making a political statement and trying to add to your financial statement Why is it [that reports of the P.M.RC. Philly incident were] in every paper in the industry? ‘Because we sent a press release out’ And who the fuck fucked with you? Oh, the P.M.RC.? They don’t even fuckin’ exist in the real world anymore.”

As Rage struggles to get the balance right, to hone its fragile mix of pop and politics, Morello, who has protested at Ku Klux Klan rallies, and cites hunger striker Bobby Sands, Che Guevara, and Malcolm X as heroes, serves as inspiration for his neophyte bandmates.

“If bands choose to sing about migrant labor rights rather than pussy, that’s all right with me,” says Morello. “We’re trying to do something most bands don’t do, which is combine music and activism. The lofty goal would be bringing down an oppressive, racist capitalistic system that feeds on the exploited and repressed.” To that end, Rage proclaims on ‘Take the Power Back”: “So-called facts are fraud / They want us to allege and pledge to their God / Bam, here’s the plan / Motherfuck Uncle Sam.” Clearly, a far cry from “It’s only rock’n’roll but I like it.”

Morello Wows the quartet’s musical cry for action as an extension of the founders’ personalities and passions. De la Rocha, a Chicano who grew up fatherless in California’s ultraconservative Orange County, has a chip or two on his skinny shoulders, exorcised partially in such new songs as “People of the Sun,” which delves into his Aztec heritage, or album cuts like “Settle For Nothing,” which explores the nonrelationship with his father. Morello is the product of a black father who was a member of the Mau Mau guerrilla army in Kenya and a white mother who is a retired schoolteacher and a founder of Parents for Rock & Rap, an anticensorship organization. The guitarist was six years old when he was first called “n****r” in his predominantly white, Chicago-area neighborhood, 13 when he found a noose hanging in his garage.

Morello, a Harvard graduate and former scheduling secretary for Senator Alan Cranston, is articulate and politically savvy far beyond his 28 years, making him the perfect foil for De la Rocha, who, at 24, is more emotionally charged. De la Rocha, apparently miffed by the lighthearted treatment afforded his politics by the British press, has decided, Riot Grrrl-style, that his art will do the speaking for him. His bandmates, however, are glad to spout off about their elusive singer.

“I don’t know if he’s going to become a political artist or the next Martin Luther King, Jr., but I’m waiting,” says Timmy C., in awe of the friend he met in elementary school. “The first day I met Zack I was in sixth grade and he was in fifth and he showed me how to rip off food from this little arcade at UCI [University of California Irvine].”

While Timmy C. and Wilk are less politically fervent than their singer and guitarist, they’re fully aligned with Rage’s various messages, yet appear fueled by personal pain more than larger political anguish. “Lollapalooza was a little strange,” relates Wilk, “because three days before the tour my dad was killed, halfway through the tour a friend committed suicide, and [band friend] Brett Kantor was murdered.”

The death of loved ones also played a big part in Timmy C.’s formative years, helping him develop the angry if ruminative personality that serves him so well in Rage. “This is the worst time of my life right now,” he says, still dealing with the fallout from his mother’s long, lost battle with brain cancer, the untimely loss of other close friends, and the current sharp focus on his band.

Though the band seems to have no problem with violent confrontation as a means to gain moral-political-social ends, raging against everything from the school system to the police and television, an incident during Lollapalooza illustrates that the young band, as Wilk ruefully notes, “is definitely four different people.” Timmy C. was arrested in New Orleans for interfering while police were harassing a homeless black man. The charges levied, he says, were public intoxication, though he claims he wasn’t drunk, and his blood-alcohol level was never tested. Also arrested were Wilk and two friends. The incident left the bassist beyond infuriated, and at the New Orleans Lollapalooza gig, Morello’s activist mother led the audience from the stage in a chant of “Fuck the New Orleans Police.”

“The only thing the experience did for me is make me realize I seriously cannot stand police at all,” says Timmy C., still irate weeks after the fact. “I’m going to vocalize to any cop I ever see that I hate him and wish he was dead, based solely on the fact that he’s a cop.” He adds, chillingly, “I promise you that one day, maybe it’ll be ten years from now, I’ll go, ‘I’m even with police.’ I’ll go, ‘I can’t tell you what I did, but I can tell you that I’m even.’ I look at it this way: They’re just going to pick me randomly, so I’m going to pick one of them randomly.” Wilk sighs in disagreement “Tim is an extremist, and that’s his personality.”

The members of Rage are first and foremost agitators, and despite the contradictions, given their place in rock’s money jungle, they are indisputably connecting, musically and politically, with a large number of kids. “I feel kinda weird quoting Chairman Mao in SPIN, but—’You learn to make revolution through the process of revolting,’” says Morello, sitting on the floor of the sparsely furnished Spanish-style apartment he shares with two roommates. “It’s an ongoing process, and the important thing is to continue to confront. You learn to be a successful activist by acting. Step one is almost complete, which is opening some people’s minds, and pissing people off on both sides of the political fence. What we’re focusing on more is real activism, on the streets of this city, doing concrete things, and being able to translate that experience into our art.” The guitarist, his new pinball machine beckoning in the dining room, appears comfortable with his chosen role as musical galvanizer of the complacent. “There’s this constant barrage of lies and propaganda coming from the TV, and just telling the truth is something that’s so radically different that it’s important to do,” he concludes. Diffusing his rant but not his message, Morello trails off, chuckling softly. “It’s my job. It’s our little work.”

Tagged: 1990s, Archives, rage against the machine