#563 (Cosmic Country), with elements of #577 (Country Soul), #580 (Outlaw Country), and #560 (Country Rock) on the Country DDS.

When the history books are written about how country music was saved in the modern era, the first chapter will set the table with how the Outlaws of the ’70s inspired the movement, how underground punks in the 90s seeded it by moving onto the abandoned Lower Broadway with Bloodshot Records giving them legitimacy, and then how a set of famous sons in the form of Shooter Jennings, Hank Williams III, and Justin Townes Earle helped set the table for what was about to come.

Then the second chapter will be all about Sturgill Simpson. Though Sturgill never achieved the commercial heights of his descendants, he was beyond foundational for paving the avenue, crafting the template, shattering the glass ceiling, creating the appetite, and moving immovable objects out of the way for everyone else to succeed, even if he broke a few things and left a bit of mess behind due to his sometimes prickly and self-important nature. There is no Tyler Childers, then Zach Bryan, then an entire industry of independent artists succeeding without Sturg.

Now the always mercurial and elusive songwriter returns under the moniker Johnny Blue Skies after completing a five album cycle and officially retiring his name as a solo artist in 2021. Though Sturgill always left the door open for returning with a band, Johnny Blues Skies is less a band, and more of a sound and a pseudonym.

Announcing his live return first with the most legendary lineup of his previous backing band (Laur Joamets, Kevin Black, Miles Miller), none of these players appear on the album. Instead we get Jake Bugg on guitar, Dan Dugmore on pedal steel, along with Sierra Hull, Steve Mackey, and Fred Eltringham. As we have seen from Sturgill in recent years especially, as a producer he prefers to field his own hand selected session players as opposed to the seasoned players on hand. Sturgill also plays significantly on the album.

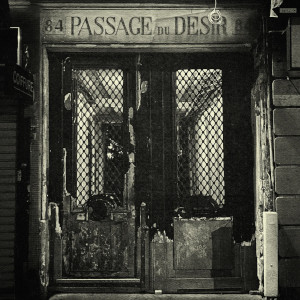

Passage Du Desir is an inspired, omnivorous work that is sometimes country, sometimes genre-less, often rock and roll, and more soundscape than singer/songwriter. It’s sometimes self-indulgent, but is mostly an enrapturing and riveting work that in part seems to explore the timeline of a relationship, from the founding of it amid a lost abyss, to its final expiration with the emotion best expressed in a guitar solo, and the seasons in between.

But more so, the album was inspired by the last couple of years of Simpson’s life and an international exploration that started in Thailand, and ended up on the streets of Paris where Simpson has been living, and where Passage Du Desir was written. There is a neighborhood, or set of streets in Paris that carry this name, along with a specific corridor. Not to come across as authoritative on local lore, but historically it was supposedly a location that included small hotels where trysts or tricks could occur out of the prying eyes of the rest of the city.

Untethered by genre, Simpson is able to explore ideas both lyrically and sonically wherever they take him on the album, which he takes full advantage of on numerous tracks. But as he says in the 7 minute “Jupiter’s Faerie,” “There’s no happy endings, only stories that stop before they’re through…” Similarly, Passage Du Desir seems to revel less in answering questions as it does in asking them, and seems to be okay, if not intended, to leave some of those questions unresolved.

Those hoping for a second coming of Sturgill’s debut album High Top Mountain, or even his magnum opus Metamodern Sounds in Country Music might be rendered somewhat disappointed. But Johnny Blue Skies owes country music nothing. Neither does Sturgill Simpson. Country is most certainly one of the aspects that Passage Du Desir is rendered in, and perhaps where it finds some of its best moments. But it’s the extended explorations in the form of “Jupiter’s Faerie” and the ending song “One For The Road” where it finds its most soaring moments.

As Simpson sings in one of the most country tracks on the album, “They don’t ask you what your name is when you get up to heaven. And thank God. I couldn’t tell her if I had to who I am.” He also tells GQ, “Sturgill served his purpose, but he’s dead, he’s gone, and I’m definitely not that guy anymore.”

But some of this is the romantic notions of how Sturgill wants to present himself to the world, because when he sings, “And that old radio still won’t play me. I can hold down the line but I can’t kick the can. Life ain’t fair and God is cruel…” it sure is reminiscent of an old Sturgill Simpson song.

Johnny Blue Skies is a nickname Simpson was given in his younger days by a Gen X barroom character in a trench coat with a Zippo lighter. It was later referenced in the liner notes of Simpson’s Grammy-winning A Sailor’s Guide to Earth. But as much as the new name and the new album open a new season for Sturgill (he says he’s written multiple albums worth of material), it’s also perhaps the most Sturgill Simpson thing he has ever done. It’s country, but expanded, enlightened, and uninhibited, rendering it boundless in possibilities for inspiring and speaking to a wide audience intimately.

Passage Du Desir is perhaps not the masterpiece some people will decree it as after a first listen—giddy that they’re even getting new music from Simpson after he said he was retired. It lacks a level of cohesion, and makes a few sonic mistakes along the way.

But the hype and excitement isn’t entirely unwarranted. The immersive experience and the inspired moments make for one of those complex musical journeys true music lovers enjoy to embark on, and it fulfills expectations that are so often left unrequited in today’s musical landscape.

8.6/10

– – – – – – – –

Purchase from Johnny Blue Skies / Sturgill Simpson

Song Reviews:

Swamp of Sadness

The song’s intro and outtro are reminiscent of mid career Tom Waits with the French macabre/cabaret influence that is meant to give rise to the setting of this album on the streets of Paris where it was written and inspired. But the heart of this song sounds very much like a Sturgill Simpson song in the way it grooves and utilizes emptiness, similar to Metamodern‘s “Living The Dream” and “Long White Line.”

If The Sun Never Rises Again

Obviously it’s the R&B sound of this track that your ear immediately picks up on, and the patently different vocal approach Sturgill Simpson takes, utilizing tones and inflections we’ve previously never heard from him. Though this adds another dimension to both Simpson and this album, it also gives ammunition to the Simpson critics who say his singing voice is a character or a put-on. Who is the real Sturgill Simpson, or Johnny Blues Skies? The song itself can still fit in that universe, but singing this in his more natural voice may have ended up with more positive results. Simpson may idolize Marvin Gaye, but he’s never going to sing like him. He can sing like an R&B guy just fine, if not even good. But that doesn’t mean he should. He should sing like Sturgill Simpson.

Scooter Blues

A decidedly simple song compared to the rest of the album, this is about Simpson’s time in Thailand and later in Paris, trying to become anonymous so that he can lose himself and find the next season of his life. It’s in the simplicity that Simpson says a lot more than what you might glean on the surface. This is also obviously one of the more “country” songs on the album, taking a bit of an island/beach “toes i nthe sand” vibe to the approach.

Jupiter’s Faerie

Going from the generally lighthearted “Scooter Blues” to this song is the album’s greatest transition. The keys part immediately sucks you in, and the song never lets go. Perhaps the album’s greatest track, some are depicting it as being about the loss of a friend. But the verses can be interpreted to be about losing multiple friends, including one lost touch with over the years, another perhaps to suicide. Either way, it feels very personal and intimate to Simpson. The only quibble is the watery effect on some of the vocals, which for some may give the intended “cosmic” element to this decidedly celestial track. But to others it will just be distracting.

Who I Am

Perhaps the most country song on the album with its Outlaw beat, it chronicles Simpson’s loss of self he experienced on his world travels. Just like “Scooter Blues,” it’s in the simplicity that Sturgill arguably communicates his most complex ideas and thoughts. Though the bigger moments on the album may get more attention, “Who I Am” definitely competes for the album’s best.

Right Kind of Dream

Though there is plenty to unravel and rave about with this track, the heavy reliance on a rather repetitive and frankly ineffective melody make this song vulnerable to being consider the album’s weakest effort. The song struggles to find where it wants to go, and also perhaps gives the album its most self-indulgent moment. “Right Kind of Dream” isn’t bad as much as it doesn’t step up to the standard set by the rest of the album.

Mint Tea

This is another country song with the phaser on the acoustic guitar, Dan Dugmore’s steel, and Sierra Hull’s mandolin really bolstering the organic roots of the track. This really is quintessential Sturgill Simpson country. And in this instance, the phaser-style vocal enhancements enhance the song with that “cosmic” element that Simpson does so well. Great song.

One For The Road

About the expiration of a long relationship, this song really leaves you asking lots of questions. Amid all of Sturgill’s world travels and moving to Paris, where exactly did this leave his family and his wife in the picture? Simpson tell GQ that he “stayed in communication” with them, but that’s all it says. This song feels very personal to Simpson, not a character study, but perhaps it is. It’s important to note that this is likely Simpson playing guitar in the extended outtro. It takes on a somewhat Pink Floyd vibe, not necessarily showing of the range of his skills, but capturing the deep emotion behind the song in instrumental form.