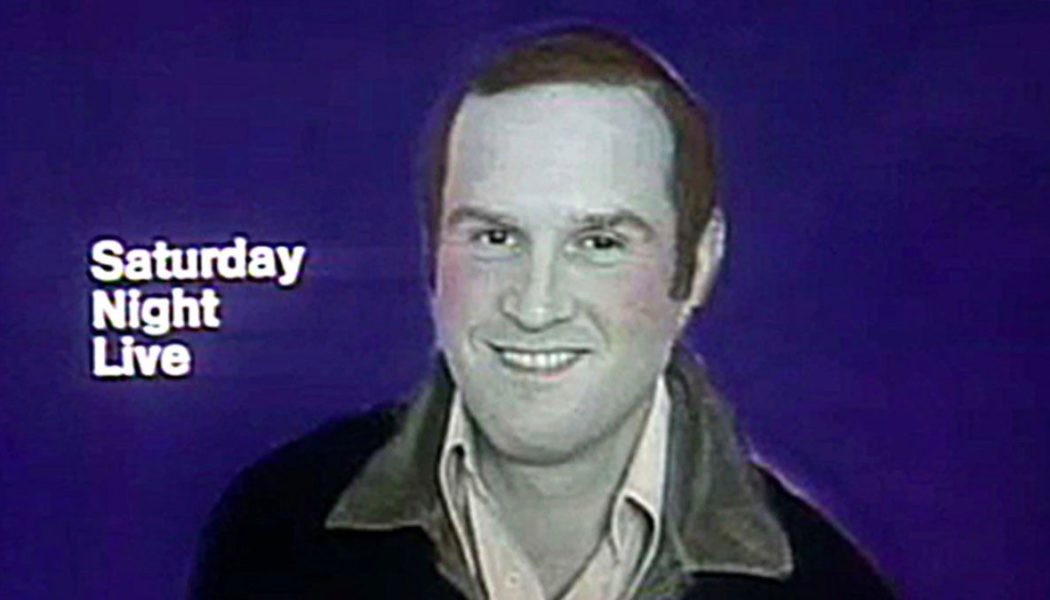

The Charles Grodin-hosted episode of Saturday Night Live that aired on October 29th, 1977 looks, from a certain perspective, like an archetypal outing from the show’s classic first five seasons. It features half a dozen popular recurring characters alongside a performance from Paul Simon, one of the show’s most frequent musical guests.

Multiple clips from this episode will be especially familiar to anyone who has caught up with old SNL bits through compilations: A Coneheads Halloween sketch and a segment on unsafe costumes produced by sleazy entrepreneur Irwin Mainway (Dan Aykroyd) were both in heavy Halloween rotation for years; the episode also features the much-excerpted first appearance from Gilda Radner’s hyperactive Judy Miller character.

Oddly, none of these bits involve the host of the episode, who passed away this week at the age of 86. Despite this lack of visibility on the episode’s clip-show mainstays, Grodin presided over a weirder and more ambitious SNL episode than the show typically produces.

Related Video

Though Grodin had plenty of projects that he steered himself, writing books and hosting a CNBC talk show in the ‘90s, some of his most memorable performances came when he would submit himself to the machinery of outside material, especially if that material seemed conventional, or a strange match with his sensibility.

This often happened with films aimed at a younger audience: think of his masterful work in The Great Muppet Caper (1981), where he both commits to and parodies the act of playing opposite a Muppet through his lustful fascination with Miss Piggy. Or recall, if you can, the inimitable oddity of 1994’s Clifford, where his loathing of his mischievous young nephew (played by an adult Martin Short) is transcendently apoplectic, as if he’s equally disgusted by Clifford and the movie’s whole insane conceit.

Grodin’s SNL appearance features no such fits of kid-movie authority-figure rage, but it does engineer an unusual friction within the show. In the backstage-set cold open, cast members wonder openly about Grodin’s ability to host the show, given that he’s supposedly missed dress rehearsal and hasn’t seemed fully committed to the show’s process.

Grodin then wanders in to explain he missed dress to buy the cast a series of tourist-y gifts; the bit continues in his opening monologue, where he confesses a certain lack of attention to the show over the past week, condescendingly referring to it as seeming “cute,” and blithely mentioning his outings to see multiple Broadway shows.

On its own, this isn’t wildly different from a typical SNL monologue; it’s easy enough to picture any number of performers doing a similar bit in a present-day segment. But this episode turns Grodin’s puzzled lack of preparedness into a runner. In between a handful of conventional sketches (the aforementioned clip-show fodder), Grodin interrupts well-known characters like John Belushi’s Samurai or the ensemble of Killer Bees to ask the cast members questions and, in the case of the Killer Bees, protest that he doesn’t fully understand the concept of the sketch.

He even invades one of Paul Simon’s musical performances, attempting to duet with him on “The Sound of Silence” whilst wearing an Art Garfunkel wig and eventually revealing that he doesn’t know most of the words. (Simon leaves, and Grodin sticks around, attempting to sing “Bridge Over Troubled Water” on his own.)

SNL has always been prone to fourth wall breaks, but it’s rare to come across an episode with the kind of running gag that might power a shorter and pre-taped sketch show. Applied to a variety-show format, this idea could easily sound tinnier with each iteration. It’s a testament to Grodin’s talent that he’s able to play it naturally; he’s so deadpan that his flaky naïveté never feels like the shtick that it is.

When he repeatedly asks an off-camera Lorne Michaels if he’ll have time to sing a song he’s prepared — which, when it finally happens, is a lovely anti-payoff in the form of a few warbled bars — he’s bearing both his everyman demeanor and his loopiness. It’s not so different from what he does in a movie like Midnight Run, where he’s both a mild-mannered CPA and a daft motormouth.

And as with his kid-movie appearances, there’s a sort of sly commentary at work when Grodin clashes with the scenery of Saturday Night Live. The version of “Charles Grodin” he plays in the episode isn’t trying to cause trouble — he simply doesn’t understand the show’s routines and touchstones are supposed to work. If given the chance, who wouldn’t step into one of the show’s weird Killer Bees sketches and ask what, exactly, is supposed to be going on? Grodin calls attention to the show’s artificiality, but does it in a deeply believable way that gets at something truthful underneath the silly material.

In the episode’s final sketch, Grodin appears as a spokesman for a “Hire the Incompetent” initiative, only to realize that the writers have used his hosting gig as a prime example. Grodin himself, of course, was a nimble, one-kind-of-a-kind pro, who leaves behind a wonderful body of work. His SNL episode is just one more example of his ability to do distinctive work within an established system — a square peg who could somehow always fit into a round hole.