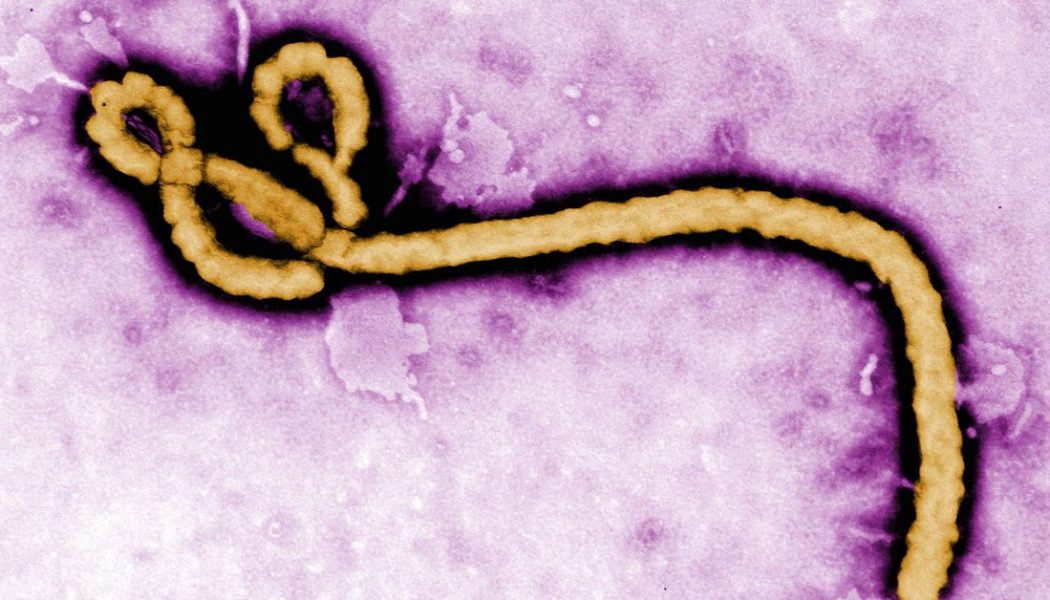

This week’s US Food and Drug Administration approval of an Ebola drug is a big milestone in drug development — one that’s closely tied to our current efforts to fight COVID-19.

Before COVID-19 started sweeping across the world, Ebola was one of the most high-profile viral diseases on the planet. “Everyone was ready to speed up and contribute and do things with Ebola that they don’t routinely do because Ebola is such a dire situation,” virologist Daniel Bausch told The Verge’s Justine Calma last August. “There are a lot of bad diseases in the world, but there’s not many that provoke the same sort of response and kind of an all-hands-on-deck approach to things.”

More than a year later, and the Ebola experiments have finally paid off in more ways than one. The drug is an antibody treatment called Inmazeb developed by Regeneron, and dramatically helped increase survival rates in Ebola patients during an outbreak in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (DRC). In addition to having a drug capable of treating Ebola, the trials also provided a blueprint for responding to future ‘all-hands-on-deck’ viral outbreaks. Researchers at the time piloted ways to responsibly conduct clinical trials in the middle of deadly outbreaks. Now, some of the same techniques that were piloted during the Ebola epidemic are being used to design clinical trials for COVID-19 treatments today.

The trial for the Ebola drugs focused on four possible treatments. Two of them, remdesivir and ZMapp, didn’t dramatically reduce death rates in Ebola patients — at least not compared to their competitors. The other two had vastly better outcomes increasing survival rates among some patients to between 89 and 94 percent. They both used lab-grown antibodies known as monoclonal antibodies to help cure people infected with the virus. One of the successful drugs, REGN-EB3, later became Inmazeb.

At the time, it was a new way of doing things. During the deadly outbreak of Ebola in West Africa between 2013 and 2016, clinical trials moved too slowly, and researchers weren’t able to get enough data to draw conclusions about potential treatments. The scientists knew that Ebola would come back, and wanted to find a way to quickly test treatments during future outbreaks of the disease. The World Health Organization and many other international partners took the lessons from the West African outbreak and came up with a framework that could be used to ethically conduct clinical trials during future outbreaks.

The researchers put the plan into action when an outbreak started in the DRC in 2018. They faced particularly challenging circumstances, including distrust of government and health officials, unstable power supplies, and regional violence. But it still worked. “This trial showed that it is possible to conduct scientifically rigorous and ethically sound research during an outbreak, even in a conflict zone,” the researchers wrote in a report published in the New England Journal of Medicine in 2019.

The success of the 2018 Ebola trial, and others like it, are part of what helped COVID-19 research get going so quickly after the virus started spreading. Back in February, researchers had already started testing treatments, modeling their efforts off the Ebola trials in 2018. “What we learned from Ebola is definitely something that is helping us to be even better during this outbreak.” Andre Kalil, a professor of internal medicine at the University of Nebraska Medical Center told The Verge’s Nicole Wetsman in February.

There’s still a long way to go. We’re starting to see early signs of what drugs might work to treat COVID-19 under certain circumstances, and which might not. (Remdesivir got emergency approval by the FDA in Maybut it is now on thin ice again). But even at remarkably fast speeds, it still took two years for the Ebola treatment to go from clinical trials to full FDA approval. It probably won’t take quite as long to see emergency approval of other COVID-19 treatments, but full approval may still be a distant speck on the horizon — even with all hands on deck.

Here’s what else happened this week.

Research

The Great Barrington Declaration’s “herd immunity” strategy is a nightmare

This pandemic is set to go on for a long time. Many people would like to move on, and some have proposed some pretty unethical ways to do it. At Vox, Brian Resnick breaks down why a proposed ‘herd immunity’ strategy is a nightmare — and looks a lot like giving up.

(Brian Resnick/Vox)

A rare Covid-19 complication was reported in children. Now, it’s showing up in adults.

A strange inflammatory syndrome appeared in some children with COVID-19 earlier this year. The condition is now showing up in a few adults, but it still seems rare.

(Erika Edwards/NBC)

‘Nobody has very clear answers for them’: Doctors search for treatments for covid-19 long-haulers

Researchers and doctors are still trying to figure out how to care for COVID-19 patients with symptoms that just won’t go away.

(Lenny Bernstein/Washington Post)

Development

NIH paused Eli Lilly Covid-19 antibody trial because of safety concerns

An antibody treatment trial was paused this week amid safety concerns. Stat reports that the NIH paused the trial because one of the two groups — either the placebo or the treatment — was doing better than the other.

(Damian Garde and Matthew Herper/Stat)

Johnson & Johnson pauses COVID-19 vaccine trial due to unexplained illness

Another trial, this one for a vaccine, was halted this week. An unexplained illness in a participant caused the trial to pause. It’s the second COVID-19 vaccine trial to be put on hold. Two vaccine trials, run by Pfizer and Moderna are still underway in the US. (Nicole Wetsman/The Verge)

Pfizer Says It Won’t Seek Vaccine Authorization Before Mid-November

For a while, Pfizer promised that it would have results from its vaccine trials by mid to late October. Now, they’re saying that while they might have some data by the end of the month, they’re not going to seek FDA authorization before November at the earliest.

(Katie Thomas and Noah Wieland/NYT)

Remdesivir Fails to Prevent Covid-19 Deaths in Huge Trial

A WHO trial of remdesivir found that it did not prevent deaths. The analysis has not been peer-reviewed yet, and some researchers say that the trial was not designed properly. (Katherine J Wu/NYT)

In the US, 50 States Could Mean 50 Vaccine Rollout Strategies

Maryn McKenna takes us through the potentially messy rollout of a future COVID-19 vaccine.

(Maryn McKenna/Wired)

Perspectives

The Guardians of Elmhurst

“Almost 4,000 people work in Elmhurst Hospital, and around 3,000 of them are women.” Mattie Kahn highlights four of the women who helped keep Elmhurst Hospital running during New York City’s horrifying COVID-19 spike earlier this year.

(Mattie Kahn/Glamour)

More than numbers

To the more than 39,393,994 people worldwide who have tested positive, may your road to recovery be smooth.

To the families and friends of the 1,105,462 people who have died worldwide — 218,602 of those in the US — your loved ones are not forgotten.

Stay safe, everyone.