When the test came back positive, Quinn* felt like he was getting a second sentence. “I believe that they sent COVID here to kill us. Simple as that,” he says. He’s a father living at San Quentin State Prison and one of over 2,200 inmates who’ve tested positive for COVID-19. The correctional facility, located in Northern California, is the center of the largest coronavirus outbreak in the country.

San Quentin was likely a preventable tragedy. Since March, experts have been warning that prison outbreaks of COVID-19 would be deadly and calling on federal judges to release inmates and reduce the size of the prison population.

That happened too late in California. Instead, the California Department of Corrections and Rehabilitation (CDCR) moved men away from a prison in Chino, which was battling an outbreak, to San Quentin, which was virus-free. In doing so, they created a second hotspot — one even more deadly than the first. By July, more than a third of people at San Quentin had the virus, according to a report in Nature. By August, 24 inmates were dead.

America’s failure to stop the virus from spreading in prisons is a key piece of its failure to contain the virus at large. Tens of thousands of people in prison have tested positive for the virus. From March through the beginning of June, the number of COVID-19 cases in US prisons grew at a rate of around 8 percent per day, compared to 3 percent in the general population. Of the top 20 largest disease clusters in the country, 19 are in prisons or jails.

To the men at San Quentin, this doesn’t feel like an accident. Speaking to The Verge on contraband cellphones, inmates discussed the systemic failings that led the facility to become a viral epicenter — failings they interpreted as intentional acts of aggression. While the men are largely cut off from the outside world, information trickles in, and conspiracy theories abound.

One theory, which Quinn believes, is that prison authorities released COVID-19 on purpose to kill off the prison population. “The governor said they weren’t going to execute people on death row anymore. So they sent the virus here to do what? To kill off people on death row,” he says. “They cost more money than anyone else here. So people like me are getting swept up in the process.”

His concerns may sound merely like rumors, but they reflect a deep-seated mistrust in the institution. That mistrust is, in many ways, warranted: while CDCR might not have intentionally released COVID-19 into the prison, months of political jockeying and legal fighting slowed the prison’s response to the pandemic and directly contributed to the outbreak. Instead of taking steps that could have kept inmates healthier, the system went down a path that made it easier for them to get sick.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21823380/acastro_200827_4167_sanQuinten_0002_03.0.jpg)

The first inmate in the California prison system tested positive for COVID-19 in March. Just after the case was reported, Scott Kernan, a former secretary of CDCR, called the prisons a “tinderbox.” Then, on March 25th, lawyers and advocates filed a motion asking federal judges to order the state to reduce the prison population and release inmates with health conditions that would put them at risk for severe disease.

The system had a critical window to contain the virus, said Marc Stern, a correctional health care consultant and former assistant secretary for health care at the Washington State Department of Corrections, in an expert declaration accompanying the March 25th motion. “To be effective in reducing the spread of the virus, these downsizing measures must occur now.”

The state of California pushed back against those calls for inmate release. The state said it had already taken steps to protect people in the prisons from COVID-19: prisons suspended the intake of new inmates, prevented visitors, and planned to transfer people who lived in riskier, dorm-style housing. Besides, releasing medically high-risk inmates would put a strain on local health systems, state attorney general Xavier Becerra wrote in court filings in March.

The decision to not let in visitors was hard on inmates, like Quinn, who rely on family visits to stay hopeful. Quinn’s family sees him when they’re able to make the time-consuming trip. In the past, he tutored his sibling who had trouble with homework, and spoke to his mother and daughter frequently. Now, he’s not sure when he’ll see them again.

Since the outbreak started, Quinn has hardly left his cell — a sparse four and a half by ten-foot, eight-inch space that he shares with one other person. He rarely has access to a shower. To try to stay healthy, he’s been drinking water and working out, but it’s hard with such limited floor space. Aside from badly chapped lips and a slight fever at the beginning of July, the worst symptom has been crippling anxiety.

When we talk, Quinn tends to discuss why the prison isn’t doing more to keep him safe and what might happen if the outbreak doesn’t improve. His cellmate, who also has the virus, is convinced he’s going to die. He also thinks the prison system is trying to kill him.

The Verge emailed San Quentin twice, and called five times, to request comment for this article. It did not receive a response.

Information travels quickly in prisons and jails, says Mary Rayne, a former West Virginia prison librarian. The facilities are news deserts, and any new bit of intel that squeezes in through cellphones or in letters is a valuable commodity. Anything that feeds on existing anxiety of prison life is sure to circulate widely. Rumors that the system is planning to exterminate inmates are familiar, Rayne says. “I worked in a prison where my circulation assistant said to me one day, ‘You know, if they ever declare martial law, they’re going to gas us,’” she says.

These types of rumors spread because inmates don’t trust the system charged with keeping them healthy, says Craig Haney, a social psychologist and a professor at the University of California, Santa Cruz who studies incarceration.

“Prisoners become accustomed to living in an environment where they feel people don’t have their best interests at heart and treat them as if they are not fully full human beings,” Haney says. “It’s not at all surprising that prisoners might come to believe that the prison system might have done this.”

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21823529/acastro_200827_4167_sqLinebreak_0004_05.0.jpg)

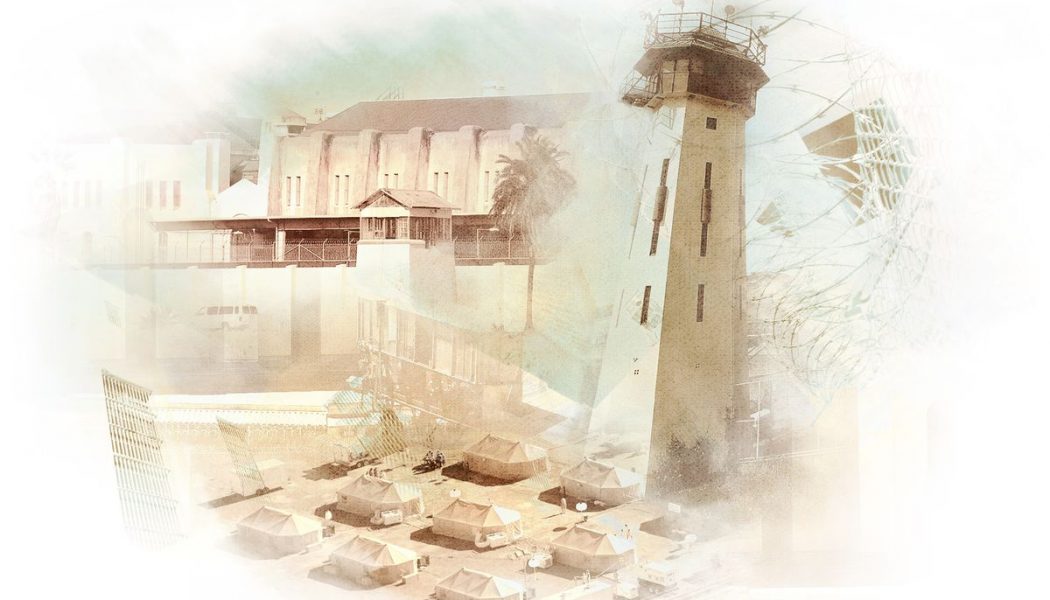

From the outside, San Quentin looks like a castle overlooking the San Francisco Bay. It’s the oldest prison in California, the grounds split up in a horseshoe of buildings that house different groups of inmates. The four cell blocks — named North, East, South, West — are five stories high and have roughly 500 cells. H Unit, which is designed more like a dormitory, is partially reserved for men with documented mental health issues.

Quinn lives in a sparse cell populated by a bunk bed, a toilet, a sink, and a small cabinet. He gets three meals a day, two of them cold sack lunches that typically consist of a boiled egg and a slice of bread or an apple and a baloney sandwich. Dinner — the prison’s one hot meal — is cold by the time it’s served. “The food doesn’t get you full,” Quinn says. “It’s the same thing over and over.”

In the spring, as part of COVID-19 precautions, staff members on the mental health team selected some men to move from H Unit to North Block, in an effort to create more space. “We were forced to decide which guys were stable enough to go up there [to North Block],” a social worker named Erica* tells The Verge. “We had to come up with all these names. None of us wanted any of them to move.”

Erica was unable to continue seeing her patients after the move — the prison was worried about the virus spreading from inmates to staff. Recently, however, she heard that one of her former patients tested positive for coronavirus in North Block. The news confirmed a feeling she’d had for some time: the prison didn’t care about its inmates. “Corruption is everywhere,” she says. “These people make decisions and don’t care who it affects.”

As inmates in San Quentin were shuffled between buildings, COVID-19 was already spreading through the California Institution for Men (CIM) in Chino, over 400 miles away. The number of inmates testing positive grew steadily through April, and by May 13th, 397 inmates had tested positive. By May 20th, about 599 had contracted the virus. Over two dozen of those inmates had severe enough symptoms that they had to be hospitalized outside the prison. Six had died, including a 65-year-old man close to parole. Each of the prison’s four facilities had outbreaks. In one of the dorm-style housing units, where inmates sleep in rows of bunk beds, over 60 percent of the residents had the virus by that point.

The legal battles meant inmates wouldn’t be released. But no one — not the state, the lawyers, or Clark Kelso, the federal receiver appointed to oversee medical care in the prison system — thought it was a good idea to transfer inmates between prisons. Transfers risked additional outbreaks, the Prison Law Office wrote in May 13th court filings, and should only happen if there’s enough testing to ensure that the inmates transferred don’t pose a risk to the prison to which they’re heading. The California Correctional Health Care Services (CCHCS) agreed, saying that moving inmates risked spreading the virus between prisons. CDCR wasn’t moving inmates.

But by the end of May, the state of California was nevertheless making plans to move about 700 medically vulnerable inmates out of CIM and over to other prisons. Kelso drew up a strategy described in a May 27th court filing: if the risk of keeping medically high-risk inmates where they were was higher than the risk of transfer, the state would consider moving them.

Every single housing unit in CIM, at that point, had at least one case of COVID-19. There was nowhere inside the prison to move the at-risk inmates, so Kelso and the secretary for the CDCR determined it was riskier to leave them there than to move them.

“We asked for releases, and they didn’t occur,” says Don Specter, the executive director of the Prison Law Office. “The receiver decided it was worthwhile to try and transfer some folks and get them out of harm’s way.”

Some of those high-risk inmates were set to move to San Quentin. They were supposed to be tested for COVID-19 before they left to ensure the transfer didn’t lead to another outbreak.

“Obviously,” Specter says, “that didn’t work.”

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21823348/acastro_200827_4167_sanQuinten_0003_02.0.jpg)

CCHCS didn’t have guidelines for when people should be tested for the virus before they were transferred. Many of the negative COVID-19 tests for the 120 men were more than a week old when they were transferred from CIM to San Quentin on May 30th. By the time buses left CIM, some inmates may have contracted the virus. Bus drivers and security who worked on the move also weren’t tested and may also have been the source of the outbreak. It’s hard to say for sure how the virus got into San Quentin, since contact tracing wasn’t reported.

There’s no evidence to suggest that it happened intentionally, says Brie Williams, a doctor who advised the state on how it should respond to the San Quentin COVID-19 outbreak. “That is such a devastating allegation, or rumor, and I don’t know anything to suggest that it’s true,” she says. Williams is also the director of the Criminal Justice & Health Consortium at the University of California, San Francisco.

The transfers happened because attorneys were terrified for their high-risk clients in CIM. “They identified people who were older or seriously ill to safeguard their health,” Williams says. “Then things went terribly wrong.”

It didn’t feel that way to Quinn. When he found out about the Chino transfers, it made the monthslong ban on visitors seem pointless, even cruel. His mother had been forced to cancel a trip she’d scheduled for this summer. “It was traumatizing even before you know if you got it or not,” he says. “Knowing they brought 121 men in here, and the numbers are rising every night…”

After the men from Chino arrived, people got sick. Rumors ran wild. The prevailing belief — the one echoed by the inmates who spoke to The Verge — was that the outbreak was deliberate. “I told the nurses, I think they’re trying to kill us,” Quinn’s cellmate says. “I don’t believe I’m going to make it out of here.”

When Quinn got tested for COVID-19, it took him two weeks to get his results. At the start of summer, the California prison system was struggling with inadequate COVID-19 testing, much like the country at large. San Quentin had the opportunity to get free coronavirus tests from researchers in the Bay Area but declined the offer. Results were taking so long that Quinn assumed he’d tested negative. Then he got a letter saying he had the disease.

The staff had their own theories for why people got sick. “I’ve never seen anything quite like this where they knew the men were sick and moved them,” says Erica, the social worker. “When you go through all the possibilities — me and all the staff members were talking, it comes down to that. It must have been on purpose — there’s no other explanation.”

Paranoia is always widespread in prisons and among inmates. “It’s a natural human response in an environment where you can’t control things yourself,” social psychologist Haney says. The health care inmates get in the best of times is regularly inadequate, and it’s maintained by lawsuits, not by what’s medically necessary. The pandemic only exacerbates that tension: inmates are afraid of infection, but there’s very little they can do to keep themselves safe. They can’t trust that guards are taking precautions when they’re not at work, they can’t stay away from each other, and they don’t have the usual contact with visitors, which makes things feel more stressful.

That environment makes it easy for inmates to feel like the people in charge are intentionally trying to make their lives worse. They’re reluctant to cooperate with health staff, which makes controlling the outbreak more difficult. Some inmates were wary of getting tested because they didn’t trust the medical staff at the facility — they worry that they could be pulled from a familiar cell and put somewhere worse. When prison officials tried to move inmates to cells lower in the building, they refused, over fears the virus particles would fall into their cells from above. “Dudes cough and sneeze, everything seems to fall,” Quinn says. “If you move me downstairs, below someone who has it, you put me at more risk.”

The outbreak stripped inmates of any sense of control or autonomy they may have been able to hold onto. “In this pandemic, where many of us feel like we’ve lost our freedoms and we’ve lost our ability to control our life, and it’s disconcerting and disorienting — it pales in comparison,” Haney says. “There is an undercurrent of helplessness in these environments.”

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/21823530/acastro_200827_4167_sqLinebreak_0003_05.0.jpg)

COVID-19 is still burning through the California prison system. Three inmates from San Quentin were transferred to the California Correctional Center in rural Susanville, sparking another outbreak. Cases are climbing in the California Institution for Women. Over 10,000 people incarcerated in California have contracted the virus — 57 have died.

The number of active COVID-19 cases in San Quentin has dropped off to a few dozen, according to the CDCR tracker. But inmates are still crowded into cells. Images on social media from inside the prison show dirty floors and garbage snagged on barbed wire barriers. Quinn is still there and still sick. So far, he says the prison infirmary hasn’t given him any medication for the virus, though he was told to stay hydrated and take Tylenol.

There is one small bright spot on the horizon. In July, California Governor Gavin Newsom announced he would release 8,000 inmates by the end of August, starting with those who have 180 days or less left to serve, according to the San Francisco Chronicle. Even so, the Prison Law Office says that the plans aren’t aggressive enough and wouldn’t reduce the populations in the prison enough to get outbreaks under control. They’re pushing to make more people eligible for release.

Quinn won’t be eligible to leave prison for years, but the announcement made him hopeful that he too could eventually get out. “It’s like a lottery,” he said. “You never know.”

San Quentin is now letting men back onto the yard, so they aren’t stuck in their cells all day. After weeks of being indoors, it’s a welcome change. It also allows new opportunities for information to spread around the prison. So far, many of the rumors circulating are about who will get out and when.

Quinn’s mom, who recently had surgery on her leg and is struggling to walk, is anxiously waiting to see if her son will be released. She helped him line up a job working construction for when he gets out. He has a place to stay with her cousin. “I feel for my baby in there,” she says. “It’s been very scary not knowing what’s really going on in there. San Quentin has a death row area, but it seems they’ve turned the whole place into death row now.”

*Names were changed to protect the identity of those involved.