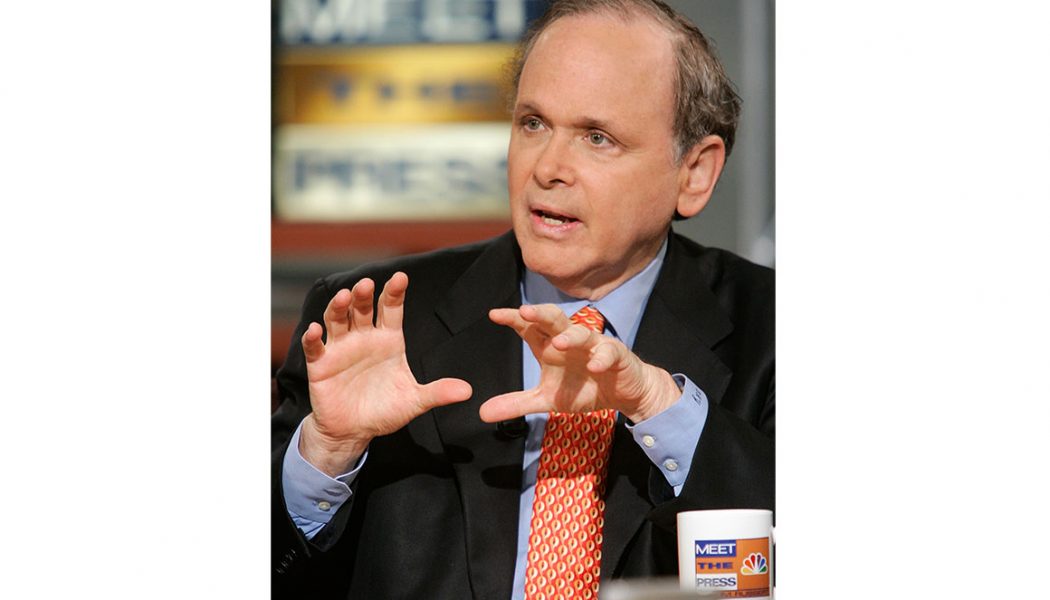

Prognosticators often lean on tropes to convince audiences that everything is changing — but when Yergin looks at the energy landscape and says “I think this is one time when this time is different,” it carries a weight. He joined POLITICO by telephone this week to make sense of the industry’s developments.

The following has been condensed and edited for clarity.

In its most recent annual energy outlook, BP says oil demand has plateaued and renewables and electricity will begin to take market share. Many people remember when predictions about peak oil production emerged over a decade ago, which never came true, but what are your thoughts on forecasts that the world has reached peak demand?

You know, that was one of the one of the questions that I really had to deal with and struggle with in writing “The New Map.” I think that we still have about another 10 to 12 years of demand rising before we hit the peak. Then when we hit the peak it’s not a plummet and collapse, it just starts to decline. Just one number to keep in mind is that the average car in the United States now stays on the road for 12 years, so those cars aren’t going away. But it is a time of uncertainty. A big uncertainty is how the world will change when Covid is behind us.

We’re seeing a lot of bankruptcies hitting the U.S. industry. In previous downturns, the larger players that still have cash on hand tend to buy up some of the oil and gas assets from companies that had gone bankrupt. Do you see that happening? Or maybe some companies are saying now is the time to diversify more towards renewables?

There’s a wonderful quote in “The New Map” with somebody in about 2007 saying, well, the Permian [shale formation in West Texas] is just about done. People were saying benedictions, it’s over. Now it’s turned out to be really competitive with Ghawar, the largest oil field in the world in Saudi Arabia. [The Permian is] one of the two great oil provinces in the world because of the nature of its geology and its extent. So I think that companies will go bankrupt, but rocks will not go bankrupt. Those resources in one form or another will be acquired by other companies.

We’ve seen down cycles before, and obviously the pandemic has been a huge slam on demand. And that’s certainly bad, but at some point, the coronavirus will be under control. Do you think even post-pandemic that this downturn will be different? I know it’s risky to say it’s different this time, but does it seem different this time?

I think this is one time when this time is different. To begin with, it was a demand shock of a kind that’s never happened before, where basically governments shut down their economies. I call it an economic dark age, which we’re still really struggling to get out of. But then there are these larger secular forces out there, too, which is the shift in investor sentiment compounded by low returns for investors. I think that the shale industry and the [energy] industry in general have two different sets of issues with investors: One is returns and the other is the [environmental, social and governance investment] agenda.

Europe has been leaning into ESG standards more than the U.S. so far. If we have a change in administrations at some point, do ESG issues become de rigueur?

Under a Democratic administration it’s likely that financial regulators will put more emphasis on ESG. One of the things that kind of really struck me when I sat back and looked at the whole picture is how the world divided from December 2015. There’s one era called “Before Paris” and another era called “After Paris,” after the Paris climate conference. To the degree to which Paris has become the benchmark by which people do ESG ratings and that governments use to operate and ask companies how does your strategy comport with the objectives of the Paris agreement. That has become something that is certainly spreading in the financial community. The financial community itself is feeling pressure from activists and others. ESG is going to continue to grow and managements are going to wrestle with it.

In the U.S. it seems like the oil and gas industry is almost not quite ready to wrestle with it. Do you remember a time when they were so divergent on reacting to policy or market forces, with European companies going their own way?

There’s really never been a time in recent years when you see such a wide variety of strategies with the major international companies. You have the larger European companies saying “we really want to turn ourselves into energy companies, not just oil and gas companies,” and particularly looking at electric power as businesses and looking at technology and batteries and so forth.

I think the U.S. companies are saying, ‘Well, we should really focus on being really efficient. We need to manage emissions.’ I think all the companies are very focused on carbon capture as you know, what’s going to be needed here when you actually look at the reality of the numbers.

I think one of the things that you can see is that all of the companies have kind of become venture capital investors looking to participate in technologies. But I think U.S. companies are not going in a big way into renewables. It is striking when you see the difference. There is an Atlantic gulf that separates the global industry now.

Are the U.S. companies in a little danger of basically becoming fossil-fuel sticks in the mud? I mean, one of the things we kind of talk about is whether Exxon Mobil, or the U.S. majors in general, are in danger of going the way of the coal industry, where they’re really good at what they do — oil and gas production — but the rest of the energy world has kind of moved on. And then you’re in danger of losing out if renewables take a bigger bite of the market.

Still, 84 percent of world energy comes from fossil fuel. And there’s 280 million automobiles in the United States and 279 million of those run on gasoline. It’s just the scale of change. Those supplies will be provided. There’s an energy transition, but it seems to me there’s a lot of hope and talk about when it’s going to happen. But it seems to me it’s going to be longer when you look at the embedded scale and the nature of our societies as they are now.

I think also people sometimes forget that it’s not just transportation that [relies on] oil. Look at a hospital operating room, how much of it depends on oil and plastics made from oil and gas. This famous N95 mask is an oil product. There’s more than one use, including also in medicine.

But I think there’s no question that we’re going to move into a more mixed energy system, and we’re going to see more renewables in electric power generation. And I think we’ll see as in Europe, if there’s a Biden administration, we’ll see a bigger push to push electric cars down into the fleet and into motorists’ garages.

If Europeans are dealing with a different kind of regulatory and market environment, do you think that that environment could come to the U.S. if ESG issues become something enforceable by the SEC, as Biden and Sen. Elizabeth Warren have proposed?

Yeah. I think it will. More of it will. The Biden climate plan echoes a lot of what’s happening in Europe. So I think that’s the case.

Switching over to the geopolitical side of your book. You quote early on a Lithuanian energy minister saying U.S. LNG exports to Europe would help “depoliticize” the European gas supply. Seeing what we have with Nordstream 2 and the administration’s putting pressure on Naftogaz in Ukraine, do you think that’s holding up to be true?

I think it was getting depoliticized. But then you get to Nordstream 2, which is you know, this $11 billion project that was just weeks away from being finished when the U.S. puts sanctions on it to stop it, saying it was a threat to U.S. national security. It’s not clear how. This has put the politics back into European natural gas in a very significant way.

It’s also created a lot of complications in U.S. relations with Germany with threats to actually put sanctions on a German port where the vessels working on Nordstream 2 are. And of course it’s made even more complicated by the poisoning of [Alexei] Navalny, the Russian opposition leader. When those sort of things happen you sort of say, what are the Russians thinking? That could be one of those decisive moments that has a much bigger impact.

You also discuss in the book how the U.S. can use LNG imports as kind of like an outward diplomacy. But with increased oil and gas production in the U.S., we’re also a bit more free in foreign diplomacy choices. Oil prices barely moved after the attack on Saudi Arabia’s oil infrastructure last year, or when the Obama administration put sanctions on Iranian oil.

Yeah. The Iranians thought sanctions couldn’t work when Obama put them on. They thought the world needed their oil. It turned out the world actually didn’t need it and if they needed oil the United States could provide it.

It’s clear that it gives us, whether you’re President Obama, whether you’re President Trump or whether it’s going to be President Biden, you’ll have a flexibility in your foreign policy that you didn’t have before because you don’t have to worry about supplies. You can see that it’s been a tremendous element of energy security. People don’t really take it into account, they don’t see it. But now this really is a major element in U.S. energy security and others see it as an adjunct to U.S. foreign policy.

I was at an event in St. Petersburg where I asked Putin — he and [German Chancellor Angela] Merkel were up on a platform, I had the first question — I said well, what are you gonna do about diversifying your economy and being less dependent on oil prices? But I mentioned the word ‘shale,’ and he started shouting at me in front of like three thousand people — an uncomfortable experience. But I realized why. It was because he saw U.S. oil and gas, this shale development, as giving the U.S. a flexibility that it didn’t have before, and in that sense diminishing Russian influence in the world.

Yeah, maybe you want to check your tea for a couple months.

(Laughs) Yeah, I wanted to put on sunglasses when I left that conference. I thought, oh boy.

There was a thought that the sheer amount of oil coming out of the U.S. would help protect against changes in supply from OPEC. Do you think that works? Saudi Arabia announced this spring a huge cut in production, but still they were able to put about 30 tankers of oil on the water. That helped to keep prices around 40 bucks or below for U.S. crude, which wasn’t enough money for U.S. shale producers to make a profit. Does Saudi Arabia still have an upper hand when it comes to calling the market?

I think we saw the new reality last April. We thought about OPEC, not-OPEC, and that’s been the kind of mental image now for decades. I think it’s now the era of the big three: It’s the United States, it’s Saudi Arabia and Russia. It was the United States, the Trump administration, that stepped in and basically brought to an end to the brief oil war between Saudi Arabia and Russia.

Trump said, you know, I’ve hated OPEC, et cetera, but realized that if you had a world of zero oil prices that this [U.S.] industry, which is an important industry, was going to go away. So I think it’s really, you know, the interaction between those three countries is what will really determine how the market functions.