From Hackers to the X-Files, being online has long been depicted as a deliberate, physical act on screen.

Share this story

The sky above the farm is the color of static, tuned to the thoughts of a dead man. Fox Mulder clings to a telephone pole, examining a nondescript grey box labeled “OPTIC FIBER CONNECTION’’ before following a thick rope of cables to a trailer parked out back. He’s about to meet an online artificial consciousness hiding in a dimly lit nest of wires and ports and monitors. It’s been using a secret government T3 network — the gold standard of high-bandwidth internet connections — to commit 32 flavors of crime and mayhem. I’m watching The X-Files’ “Kill Switch,” one of the greatest episodes of ’90s television about the internet, written by William Gibson and Tom Maddox.

The most striking thing about watching old internet and cyberculture-themed shows is that going online, from the ’70s through the ’90s, was a conscious, deliberate decision made by firing up the modem and logging on — something that became easier and far more intuitive and taken for granted after ethernet became a standard that would drive our relationship with computers. The internet became fuel for the Hollywood imagination, from the 1983 classic WarGames to dystopian horrors like Mindwarp, where people were permanently plugged into VR and ruled over by a supercomputer. Last year, Alissa Wilkinson examined how Videodrome was one of the earliest films to really anticipate the way we withdraw from the kind of connectivity that we now associate with the experience of Being Online.

It was also full of cables: big beautiful bundles on The X-Files, slender ribbons of phone cords on Murder, She Wrote. In the J. Michael Straczynski-written “Lines of Excellence,” after holding out on technology for seven seasons, Jessica Fletcher finally rejects tradition and embraces modernity in the form of computer lessons. She learns the hard way that being connected to the internet can also mean getting hacked. A year later came Sneakers, the understated 1992 comedy / techno-thriller that brought penetration testing and phreaking to mainstream audiences in a pre-Hackers world. David Strathairn, as blind phreaker Whistler, is the center of the film’s most iconic scene, where he hacks into the federal reserve system using a dynamic Braille display (there’s also just a fantastic ensemble cast of A-listers like Sidney Poitier, Robert Redford, and Dan Aykroyd).

Then came Hackers — a pure jolt of adrenaline that zhuzhed up an oft-misunderstood hobbyist subculture into a cult classic with hormonal teens dripping in Hot Topic and infectiously manic energy. Audiences back then perhaps didn’t recognize the power of a feature-length shitpost when they saw one, but Hackers was hot and young, had a killer soundtrack, and pushed hacking and phreaking and cyberculture — and the values of The Hacker Manifesto — into cinematic immortality.

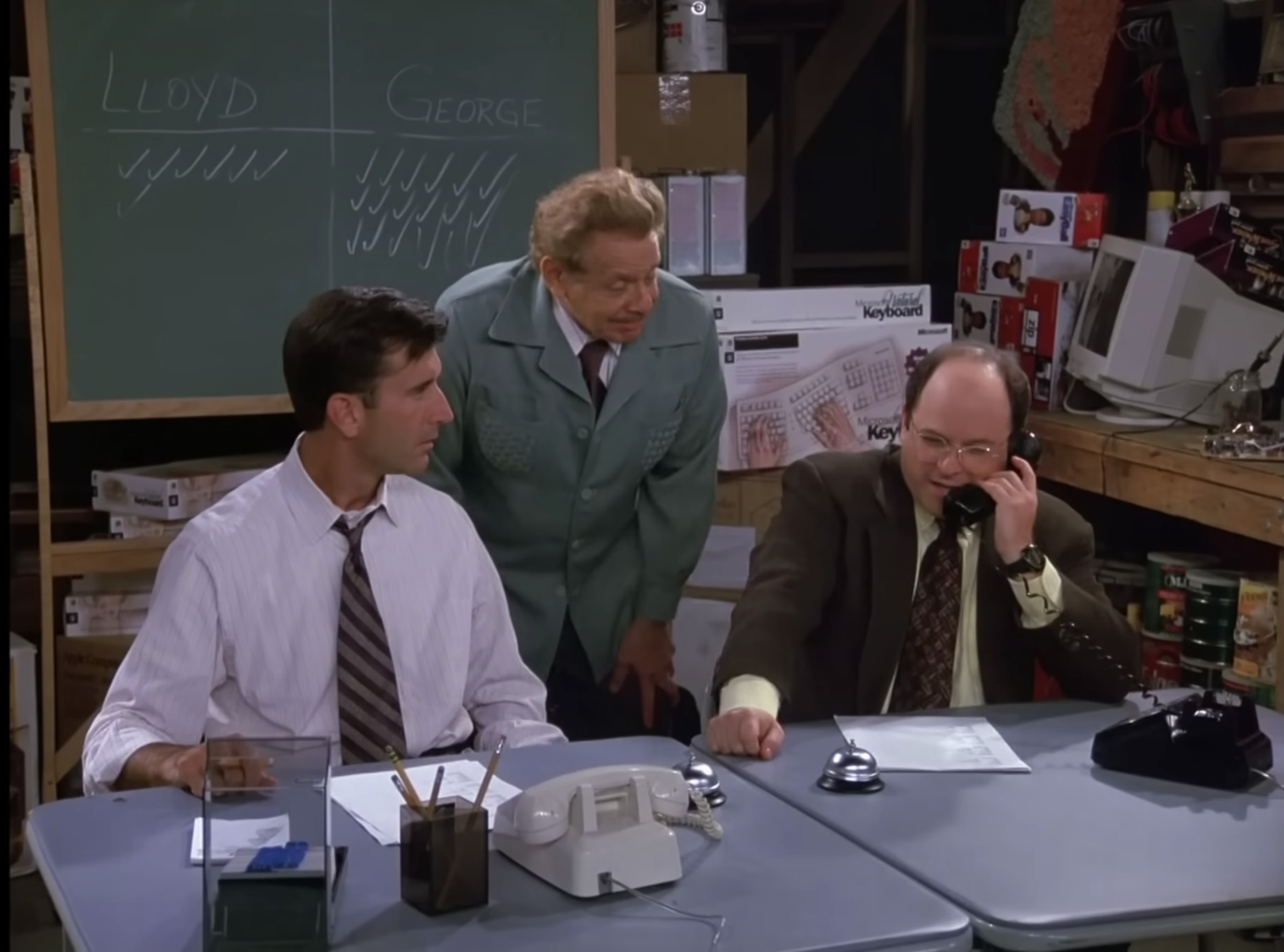

Beyond the spectacle of slick high-school seniors feeding their technolust, there’s something special about revisiting the dial-up and early broadband eras through perfectly mundane shows like Murder, She Wrote, Seinfeld, and even occasionally Law and Order (the SVU portrayals of cybercrimes are hilariously bad and deserve constant mockery). In “The Serenity Now,” George, trying to cheer up Jerry, says he can check porn and stock quotes if he buys a computer, which is frankly what I assumed my dad was doing whenever I heard the fuzzy shriek of the modem from the back of our house in 1995.

But it’s “Kill Switch” and the vision of Mulder’s limp body cradled in coils of cable, restrained by scraps of hardware, that really imbued the internet with power for a whole generation of young viewers. It wasn’t a service that your parents signed up for or a thing that nice old ladies like Jessica Fletcher paid to get set up for them. It was, through the eyes of the hackers on the show, a transcendent future that lived on the fringes of suburbia and corporate America and in the very best tradition of Cronenbergian body horror, a new and malleable infrastructural entity that we readily invited into the skeletons of our homes, businesses, and public places (the internet is now largely considered a modern utility and by some, a human right).

“Who could have predicted the future, Bill, that the computers you and I only dreamed of would someday be home appliances capable of the most technical espionage?” says the Smoking Man at the end of season 2. In retrospect, the dull limitations of his imagination make perfect sense now even though I didn’t fully understand at the time — if only he’d read even a little bit of early cyberpunk fiction that fueled so much social and technological paranoia in the early ’80s.

In season 5, we learn the origin story of the Lone Gunmen, the iconic trio of hackers who worked with Mulder and Scully and even had a short-lived spinoff show of their own. At a 1989 electronics trade convention, we meet Byers as a straight-and-narrow FCC officer who clashes with competing bootleg cable salesmen Frohike and Langly. The latter presides over backdoor games of D&D as Lord Manhammer, and there’s a lot of easy comic relief in the sheer naivete of these stereotypes. Byers hacks into ARPANET to help a mysterious woman, and the rest, as they say, is history — the three band together in a touchingly altruistic effort to “do the right thing,” and the Gunmen become radical conspiracy theorists, government watchdogs, and necessary guides to a then-bewildering frontier of virtual reality and new technologies.

It was, for better or for worse, the Lone Gunmen who made sincere feats of dorkery really fucking cool at an exceedingly awkward time for so many kids growing up around early home computers when logging on was still a distinct mechanical, physical process that led to untold riches in the ether (while logging off and avoiding the phone system was repeatedly hammered home as a way to avoid the feds).

No single piece of television nails the fear of being shunted offline better than the second season of Halt and Catch Fire’s “10BROAD36,” named after a long-dead ethernet standard developed for IEEE 802.3b-1985. The year is 1985, and fledgling online game company Mutiny is facing a cutthroat hike in data rates from a massive oil company, Westgroup Energy. The Mutiny house is the evolving heart of the season as well as the growing cultural fixation on Being Online — the coders are literally drilling into walls (and studs) and laying anarchic ropes of cable along every available surface. Their only shot is to meet Westgroup’s new benchmarks, the biggest one being to port their code to Unix overnight. Taking a page from their bootleg HBO efforts (naturally, to catch half a boob on Cat People), the punks at Mutiny disguise a Commodore 64 as a functioning AT&T Unix computer, complete with their own local broadband setup to simulate external internet access.

Of course, their working demo falls apart. There’s a pure, simple clarity in how the show links data with empowerment, at least through an idealist’s eyes; there’s much more to unpack, as well, in the episode’s time-sharing and network-sharing plot points that drive home the importance of data control. It’s startling to realize that getting elbow-deep in computer guts and stray wires isn’t part of the PC experience anymore: cables and wires are no longer inviting threads to be pulled and played with.

Toward the end of season three of Halt and Catch Fire, a new era dawns: the World Wide Web proper and the evolution of internet ontology and early indexing. In “NeXT,” we see power-marketing lunatic Joe MacMillan in peak form, talking about how they need to tackle the “tower of Babel” that is the internet according to Tim Berners-Lee. It’s pointless, he explains, to figure out what the web will become because we can’t and won’t know. “All we have to do is build a door,” he says, recalling a childhood memory of his mother taking him through the Holland Tunnel and the explosion of sunlight at the end, with all of Manhattan ripe for exploration. His pitch lands perfectly, and suddenly, there’s a clear purpose to the end of every cord: a portal.

For all the effort we made to embed them in our private spaces, cables are now unsightly, outdated things to be made obsolete in the name of convenience. It’s perhaps too fitting a metaphor for basic technological literacy today and certainly a crappier version of a hands-on past when users were forced to learn how their machines generally worked. The cyberpunk dystopia we read about as kids — a much edgier delight in ’80s fiction — has been retconned into a shapeless mainstream aesthetic that, more often than not, forgets the pliable copper threads from whence it came.

Don’t get me wrong: there are tremendous films and shows about the internet being put out today, albeit reflecting very different preoccupations with different types of technological experiences. We’re All Going To The World’s Fair, for instance, is a brilliantly discomforting time spent bathed in the light of social media. 2018’s Searching was a tale told entirely through screens, and prestige dramas (hey, Succession) routinely use text message visuals on screen.

But there’s something lost in the way we’ve left those all-important, all-consuming cables behind — ethernet is still at the heart of our lives today, even if we don’t think about it much. If the best movies about the internet and hacking are spectacles of a barely recognizable near future, it’s normcore television that offers more to chew on about the technology of the characters’ present; perhaps we’ve crossed a paradigmatic Rubicon where playing with the guts of the internet will never matter as much again.

I, for one, am happy to return to old primetime television, when the camera still lingered curiously on ports and connections, when most of us were swept up in the thrill of Web 1.0, and when the idea of pulling the plug still felt like a painless option.