I don’t know what else to call it: the Windows 11 upgrade situation is a confusing mess. Depending on when your PC was built, which components you chose, and how it was configured, there’s a decent chance Microsoft will try to scare you away from installing the free upgrade, which is available a day early today. Millions of people will likely be told their systems are incompatible, and Microsoft is reserving the right to withhold security updates if you install on older systems.

But as far as we can tell, Windows 11 is largely Windows 10 with a fresh coat of paint, and there’s a strong chance your Windows 10 computer will run Windows 11 just fine. Do we recommend it? Not necessarily, but this article might help you figure out whether your PC is ready for the ride.

Here’s a basic checklist of what you’ll likely need, and how you might satisfy each requirement.

- Basic system requirements: 1GHz dual-core CPU, 4GB RAM, 64GB storage, UEFI motherboard, TPM 2.0, DX12 graphics, 720p display

- UEFI must be enabled

- TPM must be enabled

- Secure Boot must be enabled

- Processor must be on Microsoft’s approved list if you want an in-place upgrade

- 64GB of free space if you want to dual-boot Windows 11

Before we go any further, why not give Microsoft’s official PC Health Check tool a try? (Direct download here.) If you pass, you’re probably already fine. Just wait for the official Windows Update and you should be good.

But if not, your first steps should probably be to turn on your TPM and Secure Boot setting.

How to turn on TPM

As we discussed in June, you probably already have a Trusted Platform Module (TPM) in your PC, built into your desktop or laptop motherboard or your CPU. (If you don’t, there are hacky ways around it, but let’s start by saying you do.)

It’s possible that Windows will see your TPM, and you can easily check by either running that aforementioned PC Health Check tool or hitting Win + R, typing tpm.msc into the window that appears, and hitting enter to see what kind of TPM might be there and if it’s “ready for use.”

If it’s not, don’t give up yet! It might just be disabled in your BIOS and you’ll need to go hunting for it.

Once you’re in the BIOS, the TPM setting goes by a wide variety of names. (My desktop motherboard called it “Intel PTT” (Platform Trust Technology), but it might be an “AMD PSP fTPM” or simply a “Security Device.”) If you don’t see an obvious place to check, Microsoft suggests looking for a sub-menu called “Advanced,” “Security,” or “Trusted Computing.”

Oh, and depending on your BIOS, you may need to use your keyboard’s arrow keys to move and possibly even the PG UP / PG DOWN buttons to turn things on and off again. (Apologies if you know this, but it’s no longer safe to assume.)

Got it? Great! But don’t leave the BIOS just yet.

If you only have a TPM 1.2 module, not TPM 2.0, you still aren’t out of luck: Microsoft will let you modify a registry key in Windows to allow upgrades “if you acknowledge and understand the risks.” If so, hit Start, type regedit, search for “HKEY_LOCAL_MACHINE\SYSTEM\Setup\MoSetup” find the AllowUpgradesWithUnsupportedTPMOrCPU key, and set its value to 1.

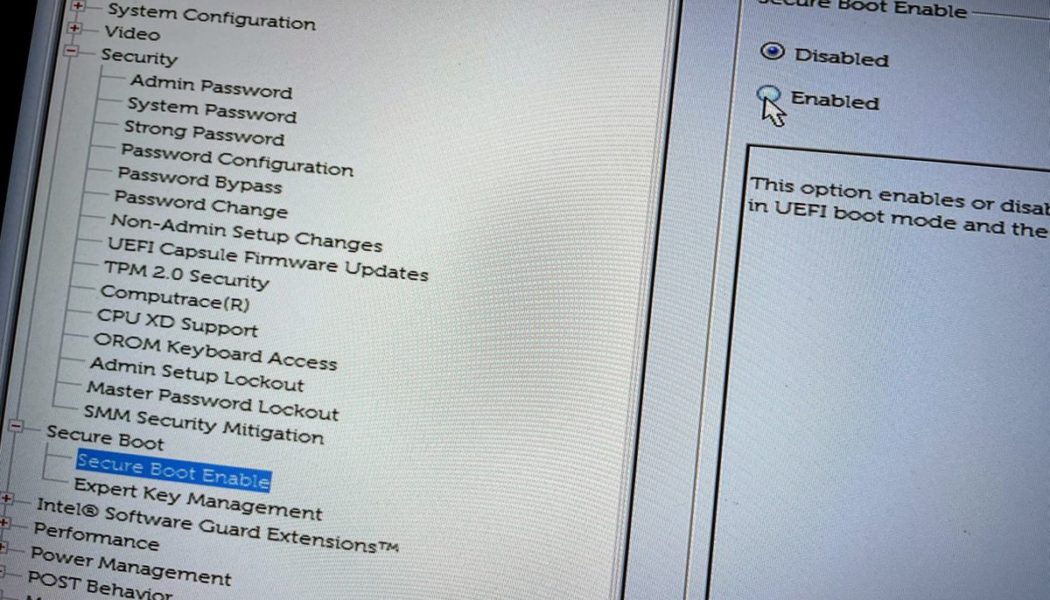

How to turn on Secure Boot

Once you’re in your motherboard’s BIOS, you should likely also be able to locate a sub-menu for Secure Boot. It might be buried in a “Security,” “Boot,” or “Authentication” tab.

Flick it to “Enabled,” if it isn’t already.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22900233/secure_boot_uefi.jpg)

If you’d like to check whether Secure Boot is already enabled from Windows (perhaps saving yourself a trip to the BIOS), there are a couple of ways to do that, too: in addition to Microsoft’s PC Health Check tool (direct download), you can hit Start and type in System Information, and launch that app to see a variety of things, including Secure Boot toggle status and your current BIOS mode.

I can’t turn on Secure Boot, and I’m not sure I have UEFI at all.

Unless your PC is very old, you probably have the option of a UEFI BIOS, but you might not actually be using it right now. You might be on a “legacy” BIOS that uses MBR (Master Boot Record)-partitioned drives instead of the modern GPT (GUID Partition Table) standard that Windows requires for UEFI.

If that sounded like a load of alphabet soup, you may want to stop here! Microsoft does have an MBR to GPT conversion tool, but messing with partition tables fundamentally puts the data on your drive at risk. That tool didn’t work for one Verge staffer, who went on to use a different method that wound up wiping his entire partition. (Sorry, Cam!)

If you don’t care about your data, you might as well do a clean install of Windows 11. And if you DO care about that data, why not try out a dual-boot of Windows 11 instead? Besides, those may be your only easy options if your CPU is too old.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22900459/windows_11_windows_11_cpu_not_supported.jpg)

“The processor isn’t supported for this version of Windows.” Help!

While there are always hacky ways to get around Microsoft’s restrictions — one Verge writer tricked the Windows 11 updater using a Frankenstein-esque combination of old and new ISOs — the company is generally not allowing PCs with older CPUs to install Windows 11 over their existing Windows 10 operating system and keep existing settings and files.

That means you’ll generally need to create a new drive partition or overwrite an existing one, and it makes dual-boot particularly enticing.

You can find Microsoft’s official lists of supported processors at these links:

Generally, Intel 8th Gen or newer CPUs are supported, as are AMD Ryzen 2000 and newer.

How to dual boot Windows 11 or clean install the OS

Whether you’re starting from scratch or just dipping a toe in the water with a dual-boot, the process should be roughly the same: you’ll need to free up some space, download the Windows 11 ISO or tool, burn it to a bootable drive, and use it to install Windows.

For a dual-boot, you don’t need a second drive inside your PC — you can simply shrink your existing partition with Microsoft’s Disk Management tool. Hit Start, begin typing in “Create and format hard disk partitions” and hit enter to launch it. Make sure your drive has plenty of space, then right-click and pick Shrink Volume. You’ll want to shrink it by at least 65,536MB (64GB) so there’s enough room for Windows 11 — I gave my laptop install 128GB (131,072MB) just to be safe. You can’t shrink more than you have, though, and you may want to leave some space for your current OS to breathe.

:no_upscale()/cdn.vox-cdn.com/uploads/chorus_asset/file/22900501/shrink_volume_windows.jpg)

To actually install that ISO, all you need is a USB external drive — an 8GB USB 3.0 key should work just fine — and a piece of software to burn it to disk. Microsoft has its own Media Creation Tool which we’ll link to soon, and I’m a big fan of Rufus to burn my bootable USB drives using downloadable ISOs as well.

Power users might want to try AveYo’s Universal MediaCreationTool, which may be able to download the image and bypass TPM for you, too.

If all goes well, you’ll reboot your computer with that USB key plugged in to start the process. You may need to press a key like F12 while your system’s booting up and manually select your external drive, if it doesn’t automatically load.

Now, be careful to pick the right place to install Windows 11 — if you shrunk your drive to make room for a dual-boot, you’ll tell Windows to install in the unallocated space, and if you’re overwriting an existing drive for a clean install (file loss ahoy!) you’ll pick that drive instead. For a desktop with multiple drives, you may want to power off and unplug the extra ones before choosing where to install. It’s all too easy to press the wrong button and wipe out data, and we’d hate for that to happen to you.

Once you’ve got a dual-boot, it’s not too hard to switch between the two operating systems. Hit the Windows key to pull up the Start menu, type UEFI and pick Change advanced startup options, then select Restart now. Once you boot back into the advanced startup menu, pick Use another operating system and it’ll present you with your choice of OS.